MeiLin Miranda writes fantasy and science fiction set in Victorian worlds. Her love of all things 19th century (except for the pesky parts like cholera, child labor, slavery and no rights for women) has consumed her since childhood, when she fell in a stack of Louisa May Alcott and never got up.

MeiLin wrote nonfiction for thirty years, in radio, television, print and the web. She always wanted to write fiction, but figured she had time. She discovered she didn't when she had a cardiac arrest and near-death experience. She has since decided she came back from the dead to write books.

MeiLin lives in a 130-year-old house in Portland, Oregon with a husband, two teens, two black cats, a floppy dog and far, far too much yarn.

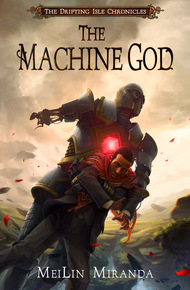

Folklore Professor Oladel Adewole has lost tenure, and the beloved, much-younger sister he's raised has died; with no reason to stay, he leaves his homeland for the University of Eisenstadt. One thing makes his new life bearable: the mysterious island floating a mile above the city, his all-consuming interest for years.

When a brilliant engineer makes it to the island in her new invention, the government sends Adewole up with its first survey team. The expedition finds civilization, and Adewole finds a powerful, forbidden fusion of magic and metal: the Machine God.

The government wants it. So does a sociopath bent on ruling Eisenstadt. But when Adewole discovers who the mechanical creature is—and what it can do—he risks his heart and his life to protect the Machine God from the world, and the world from the Machine God.

MeiLin Miranda came back from the dead to write, and it shows—there's a kind of unabashed honesty in her works, visceral and insightful and wrenching all at the same time. Add in the inventiveness of a steampunk world to that, and you've got powerful storytelling. As an extra treat, MeiLin's The Machine God is one of two Drifting Isle Chronicles in the bundle (the other is Black Mercury)—these novels are adventures in shared-universe storytelling, where the authors use an agreed upon setting that includes the titular mysterious floating island. (A third Drifting Isle tale, The Kaiser Affair, was written by another bundle author, Joseph Robert Lewis.) It's not often we get to see a world from different perspectives and different voices, and I love that we have this inventive storytelling approach in the bundle! – Susan Kaye Quinn

"Meilin Miranda writes a fascinating story about a person’s search for the greater good."

–Mihir Wanchu, Fantasy Book Critic"Outstanding - I loved almost everything about it."

–K. Rutherford, K. Rutherford Books"Ms. Miranda packs a whole lot into just a few pages -- wry and pointed commentary on academic politics and the tensions between pure and applied research, the ethical implications of the quest for knowledge for its own sake, the public and private morality of holders of political and academic power, and yes, whether or not someone at some point actually managed to build a mecha so big and powerful that it could legitimately be referred to as a Machine God."

–Kate SherrodProfessor Oladel Adewole put his cup down on the coffeehouse table. Thin, insipid, badly roasted, outrageously expensive—Eisenstadters called this coffee? At least the early Mai day was reasonably warm, warm enough to sit outside; still, scudding clouds just touched Erukso'i, the enormous island floating in the east above the city. The locals called the island Inselmond—he must learn to call it by its Eisenstadter name. He drummed his long brown fingers on the table and resumed nibbling on the sugared biscuit he'd gotten to wash the coffee down. At least these people knew how to make decent pastry.

A tiny rustling brought his attention toward his feet; small birds were searching the cobblestones for crumbs. They resembled the tiny yellow sparrows back home in Jero, but dun-colored and drab—rather a good comparison between Jero and Eisenstadt. A little brown spar- row hopped away from the clump toward him. "Tsee! Tsee-tsee-tsee- tsee- Hi! You finishing that? Tsee? Tsee?"

Jero's tiny yellow sparrows did not accost coffeehouse patrons. "Pardon?" said Adewole.

"Tsee-tsee-tseeee simple question!" said another sparrow.

"Tsee? Tsee? Share? Yes? Tsee?" chirped the little birds, hopping by cautious, hopeful degrees toward the astonished man. Adewole crumbled up the biscuit's corner and scattered it on the pavement; the birds settled down to business, hurrying from crumb to crumb until one let out a shriek. "Cat! Cat!" The sparrows united into a flock and streaked to an overhead wire, where they abused a disappointed orange tom standing where the birds had lately been. "Tsee-tsee-tsee Bad kitty! Bad kitty!"

Adewole wondered which would be harder for him to accept: Eisenstadt's aggressively sentient birds or the coffee. No, hardest to accept would be the losses that led to this backwater. Definitely that. He reached a hand into his pocket for his watch fob, and absently rolled the good luck bead attached to it.

The sky darkened, and the temperature dropped; Inselmond's shadow approached the coffeehouse as it did this time every morning. Time to go. He paid his bill, adjusted the bright purple-striped wool kikoi cloth draped across his suit-clad shoulders, and headed toward his lodgings. Perhaps his last trunk had finally caught up. He'd been here more than a month, and it still had not arrived.

When he'd first told his colleagues in Jero he'd accepted a visiting professorship at Eisenstadt—the Mueller Chair in the Humanities—they'd peppered him with advice:

"Wear the dark pants and jackets the locals do, but bring kikois to wear over them—wool or silk, not cotton. It's cold even in the summer!"

"You can find real adeesah in the city—when the other expatriates trust you, they'll point you to which Jerian restaurants use black market chicken suppliers. The others serve rabbit stew with red pepper and garlic waved over the top, slop it over the wrong kind of rice and call it adeesah. All the birds talk there, even the chickens, the stupid things! And bring plenty of dried red pepper. Those people do not believe in food with flavor."

"Also fill one of your trunks with green coffee beans and bring a stovetop roaster with you. Not that trunk. The big one. The locals don't believe in coffee, either, and those beans will be worth their weight in gold with the Jerians there—get you introduced into all kinds of society."

The advice most often given: "Don't live near the Drift. It's cold and it's dangerous." Adewole glanced again at the island's approaching shadow above the city, the shadow the locals called the Drift. The University had arranged his lodgings before his arrival. They'd given him many possibilities, but unlike some academics he did not possess independent means and lived on his salary alone; he'd had to settle for a neighborhood in the penumbra. The street lights didn't come on in the day as they did in the full Drift, but he would have preferred lodgings altogether outside the shadow's path.

As he walked, the streets darkened around him, and he realized he'd taken a wrong turn; he was walking straight into the Drift. He cast about for the penumbra, but the rows of houses made it difficult. Timers inside the street lamps ticked and tocked; the lamps flickered into life. Adewole paused, trying to regain his bearings.

"Hey, bean pole," said a young, nasal voice behind him. Something sharp poked him low in the ribs. "Don't screw around. Put yer hands up and let Artur here in yer pockets." Another boy who must have been Artur appeared. He couldn't have been more than twelve, and Adewole towered over him. A dirty bandana covered his round face; squinting eyes appeared beneath a ragged cap's brim.

"Are you mugging me, little boy?" said Adewole.

The something-sharp poked him again, harder. "Shaddup, hands up, let's get this over with, bird-eater!"

Adewole shrugged and raised his hands above his head. "If you had asked me, I would have given you what I have, though you shall be disappointed—it is not much." Children were his soft spot, especially in recent days, and besides, better lose two pfennigs than take a knife in the ribs even if he did need the pfennigs.

A whistle shrilled. "Hoi! Stop! Hoi!" a man shouted. The something-sharp retreated. Artur and the boy with the something-sharp took off running, away from the street lamps and deeper into the Drift. "Hoi!" yelled the man again. "They went that way!" Three sturdy young men in policeman's uniforms ran after the muggers, arms and legs pumping. They were faster, but those boys were probably trickier. The whistle-blower came to a stop beside him. "ARE...YOU... HURT......SIR?" he bellowed up at Adewole.

"No, nor am I deaf, officer," winced the tall Jerian. "But I am still new to your city and would appreciate directions back to my lodgings."

"Begging pardon, sir, not everyone who comes from elsewhere speaks the lingo," smiled the police officer.

As he followed the policeman's directions back to his flat, Adewole pondered the years he'd spent learning "the lingo." Whose lingo, he'd never been fussy about; he'd always been a natural polyglot, and his mother had been a translator and teacher to Jero's many immigrant communities and tourists. The language of symbols—pictographs, hieroglyphs, talismans, runes of all kinds—fascinated him as well; so many appeared across cultures, some across every culture, and figured in his work.

Adewole glanced at Inselmond, floating in the sky to the east, perhaps the biggest symbol of them all. The island wasn't one of the world's marvels, it was the very marvel itself. Whatever event had thrown it into the air reverberated throughout the world. People everywhere told stories about the island, even in far-away Shuchun. All speculated on how the island came to be and what was up there; most stories involved an angry god, a concept frustrated agnostics like Adewole himself found hard to believe but fascinating all the same. The same stuff wove through so many stories around the world, and Adewole had made it his life's work to trace the threads. He'd always intended to come to Eisenstadt but on his own terms, not like this.

He arrived at Mrs. Trudge's boarding house, a shabby-genteel, three-story brick building stucco'ed in faded yellow plaster. Coral-red geraniums drooped in the planter boxes below each window; the Drift's penumbra starved them of just enough light they would never thrive, but not so much they would die. "Little flower," he murmured, gently flicking a petal, "I know just how you feel." He climbed the steps and went inside.