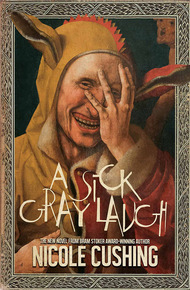

NICOLE CUSHING'S fiction has been recognized with the Bram Stoker Award®, two Shirley Jackson Award nominations, a nomination for the This Is Horror Award, and a place on the Locus recommended reading list. Rue Morgue recently included Nicole in its list of 13 Wicked Women to Watch, praising her as an "an intense and uncompromising literary voice". Her second novel, A Sick Gray Laugh, was recently released by Word Horde. A stand-alone novella, The Half-Freaks (published by Grimscribe Press) also appeared in 2019. Nicole lives in Indiana.

Award-winning author Noelle Cashman is no stranger to depression and anxiety. In fact, her entire authorial brand, showcased in such titles as The Girl with the Gun in Her Mouth, Leather Noose, and The Breath Curse, has been built on the hopeless phantasmagoric visions she experiences when in the grip of paranoid psychosis. But Noelle has had enough, and, author brand be damned, has found help for her illness in the form of an oblong yellow pill, taken twice daily.

Since starting on this medication, Noelle's symptoms have gone into remission. She's taken up jogging. She's joined a softball team. For the first time in Noelle's life, she feels hope. She's even started work on a nonfiction book, a history of her small southern Indiana town.

But then Noelle starts to notice the overwhelming Grayness that dominates her neighborhood, slathered over everything like a thick coat of snot, threatening to assimilate all.

From Bram Stoker Award-winning author Nicole Cushing comes A Sick Gray Laugh, a novel about madness, depression, history, Utopian cults, literature, sports, and all the ways we struggle to stay sane in an insane world.

A Sick Gray Laugh is a satirical take on authorial experience, from Bram Stoker Award-winning virtuoso of transgressive fiction, Nicole Cushing. Ross Lockhart says, "Gallows humor for folks who find Thomas Ligotti a little on the light side."

"…an intense and uncompromising literary voice.."

– Rue Morgue"The confidence and expertise so blatantly evident in Nicole Cushing's writing is astonishing."

– Thomas Ligotti, in reference to Children of No OneWhen I started writing this book, I vowed to keep my madness out of it.

What, exactly, do I mean by that? Simply that all the books I wrote before this one were works of fiction inspired by my personal struggles with severe depression and anxiety, and that this approach was beginning to feel a little old. How many times can I write about characters on the brink of self-slaughter? How many times can I depict characters paralyzed by obsessive-compulsive disorder? How many times are you, constant reader, capable of indulging me in my habit of obnoxious repetition?

Maybe if I were still plagued by such ailments, I'd grit my teeth, suck it up, and find a way to be satisfied with the tried and true approach that has led my work to enjoy critical acclaim. After all, while madness has not been good for me, it's been awfully good for my fiction. Reviewers, academics, and awards juries have come to expect that I'll publish a steady flow of books with titles like The Girl with the Gun in Her Mouth and Leather Noose. Unrelenting nihilism, spiked with sadism, is the trademark of my work.

But therein lies the problem. You see, shortly before the publication of my last book (The Breath Curse) my madness became so severe that I was forced to seek the treatment of a psychiatrist. My OCD had morphed into something more akin to paranoid psychosis. After decades of fending it off on my own, I reached the breaking point and asked for help. I saw an old, wizened, mummy-like doctor of mixed German and Indian descent named Sherman Himmerahd-D'janni, M.D. He prescribed an oblong yellow pill. I take two each day. Since starting this medication, my ailments have gone into remission.

So even if I wasn't bored with the subject of madness, I no longer suffer from it. And because I no longer suffer from it, I no longer feel the urgency to vent my suffering onto the page. Make no mistake, I still wield the knife of pessimism. But instead of carrying it with me day in and day out, I often put it on the shelf for weeks on end. I no longer take the time to sharpen it against the whetstone of rumination.

This is good news to my friends and loved ones. Everyone close to me seems to appreciate the change. I've begun jogging and have lost seventy-five pounds. I am tan, healthy, and more mindful of cobbling together an attractive appearance (washed hair, brushed hair, brushed teeth, shaved legs). I play softball. I am able to become fully immersed in the drama of competition. I have joined with others to form a team. I am unashamed of having cast my lot with theirs. Unashamed of marching shoulder to shoulder with them, week after week.

This may astonish you, but it could even be said that—of all our players—I'm the least pessimistic. Even during our last at bat in the last game of our 0-18 season, even as we were losing twenty to eight, I believed that we'd be the recipients of a miracle and come away with a victory. And when our final batter grounded out, I spent five minutes in a daze wondering why the underdogs hadn't prevailed (the way they always do in the movies).

What's the point of this seemingly pointless anecdote about my athletic endeavors? Simply that, for the first time in many years, I'm capable of succumbing to Moronic Hope.

This, in and of itself, implies that I've been reabsorbed into humanity (the species that, to this day, remains the only known practitioner of Moronic Hope). But there were other signs of my reabsorption as well. I enjoy the company of my fellow man. Or, at the very least, the sea of humanity no longer makes me seasick. Or perhaps it still does, but the oblong yellow pills have an effect similar to Dramamine. In any event, to impress upon you just how far I've come in reacquainting myself with the human herd, I'll say this: I've even begun to listen to two (not one, but two!) local sports radio stations. This is, arguably, the most normal activity I've undertaken in many years.

In some ways, though, I regret all these changes. There's the real possibility that, already, they've disrupted my writing mojo. Yes, I have vowed to keep my madness out of this book. But my brain has always worked best when it's obsessively contemplating death. My spirit of creation is the spirit of decay. Corpse breath has always been the wind billowing my sails. Now I have to change? Find a way to maneuver my boat through a fresh coastal gale? This will surely have a negative impact on the artistic success of my writing endeavors.

Even worse, the positive changes in my life threaten to fuck up my commercial success. What I mean is, these changes could destroy my author brand.

You do understand what an "author brand" is, don't you? It's a concept that, in recent years, has become all the rage in conversations between writers. Just Google it and you'll find ten thousand and ninety-one blog posts emphasizing the necessity of having one. But let's assume, just for a moment, that you haven't heard of the concept and you're too lazy to Google it. How can I best describe it?

Well, as I understand it, an author brand is an author's unique identity, as perceived by bookstores, readers, and reviewers. An author's unique commercial identity, you might say. (And please note that by "unique commercial identity," I mean a unique identity as summed up in a single phrase that helps consumers and tastemakers get a sense of the flavor of a writer's products.)

So you can see my dilemma: if your author brand reeks of madness and squalor, as mine does, getting well creates problems. You can't proceed as you always have before: dipping a ladle into your own mental effluvium and distilling it into effective fiction. Pharmaceuticals have re-invented Noelle Cashman, the person. Therefore, it was inevitable that they'd also reinvent Noelle Cashman, the author.

This is why I've been forced to take a decidedly different tack with this book. In the past my work has been fueled by the aforementioned distilled introspection. It typically unfolded in the following fashion:

1. I experienced a fresh, jellyfish-like sting of mental torment (or the intrusion of wormy, mildewy, half-rotten memories of past torments).

2. The mental torment (or half-rotten memories) caused several strange disjointed images to flash before my mind's eye.

3. I took the most potent of the strange images and used it as the definitive image of a story; the image that held within it all the essential characters and plot points.

(Un?)fortunately, it has been too long since I've experienced mental torment. Therefore, my old tricks no longer work. So I am forced to change my writing habits. Since I can no longer depend on the strange disjointed images in my mind's eye, I've decided to switch to writing nonfiction. That way, I can write a book focused exclusively on the world outside my head.

But which world outside my head? There are so many to choose from these days. For example, there are the worlds of Twitter and Facebook. Sometimes I think of these as the worlds of moral exhibitionism (in which social networking accounts open their virtual raincoats and flash their social, political, religious, or anti-religious virtues in front of you, unbidden). Other times I think of these as the worlds of moral pornography (in which we voluntarily stare at the penetration of vice by virtue, and caress our own private parts—whatever they may be—in sync with the rhythm of the rutting).

Will I be writing about these worlds and their attendant moralizing?

No. I find social networking to be a dull obligation at best. (An obligation to push my author brand, that is.) At worst, it may be a tool of corporate and/or government surveillance. Furthermore, I will not get on a soapbox to endorse any social, political, religious, or anti-religious causes, even those that I privately champion. You see, I don't read a lot of polemical nonfiction, so why would I choose to write it?

But surely, you're thinking, there are other worlds out there to explore in a work of nonfiction such as this. Worlds that afford a less stridently moralistic tone than that of Facebook and Twitter.

Yes, of course. I know that. For example, there's the world of glossy sports magazines. The world of publishers dedicated to translating works of Russian, Czech, and Icelandic literary fiction into English. The world of lower-middlebrow American bestsellerdom. When I say I'll be writing about "the world outside my head," do I mean I'll be writing about any of these worlds?

Alas, no. While I've brushed against all these worlds, I don't feel very connected to any of them. I'm not a citizen of any of those worlds. I'm a tourist who has infrequently visited them.

I don't think I should write about worlds I know only from tourism (especially in this, my first work of nonfiction). Natives of such realms would rightly point out my superficial treatment of the subject. Better to write about something closer to home.

What about the world of twenty-first-century movies? Is that the "world outside my head" on which I'll be focusing?

No.

At the risk of sounding like an old fart who is out of touch with pop culture, I must confess that even now, during my upswell of mental health and tolerance of humanity, I seldom go to the movies. Even looking at the trailers makes me groan. There's too much CGI. Everything is a boilerplate kaleidoscope of pseudo-outrageous action in the manner of a video game. I say "pseudo-outrageous" because every 3D twist and stretch and explosion is there to serve reliably stale, melodramatic storytelling. (This, by the way, is an aesthetic judgment—not a moral one.)

What, then, about the world of twenty-first-century television? Surely that's the "world outside my head" that I'll be focusing on, right? Unlike the movies, broadcast television offers various news and sports programs presented in high-definition digital clarity. I consider myself to be a citizen of that world, don't I?

While I've watched several minutes of high-definition NFL broadcasts, I must hasten to add that I've never been able to finish an entire game. Something about high-definition digital video seems exaggerated. The world shown in such broadcasts doesn't look like the real world at all. It looks like the real world after it has been polished three days straight with Turtle Wax. How could I possibly write about such a world? It would be impossible. For starters, I don't have the necessary tools. To depict such a waxy world I'd have to rig my printer to use cartridges full of Turtle Wax instead of ink. Anyone who knows me well can tell you I'm not that mechanically inclined.

No, I decided to write about a world unmediated by any camera and/or display screen. It is simply the world as it appears outside the window of my home office.

At this point you may be thinking something like the following: What do you see outside that window, Noelle? How can it possibly be worth writing about? If you limit yourself to a subject so prosaic, you'll sell yourself short. Don't go for the low-hanging fruit! Why do you even look out there anymore? What can you find in the world outside your window that can't be found a thousand times in a Google image search? How can you possibly claim that it's more deserving of my attention than MSNBC's coverage of the latest school shooting, or The New York Times' coverage of the National Book Awards? How can a nonfiction elaboration on this prosaic view possibly be worth our time? These are entirely reasonable questions. Be patient. All shall be revealed.