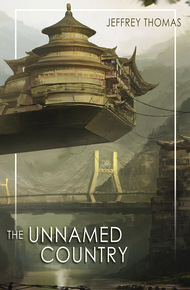

Jeffrey Thomas is the author of such novels as The American (JournalStone), Deadstock (Solaris Books), and Blue War (Solaris Books), and his short story collections include Punktown (Prime Books), The Unnamed Country (Word Horde), and Carrion Men (Plutonian Press). His stories have been reprinted in The Year's Best Horror Stories XXII (editor, Karl Edward Wagner), The Year's Best Fantasy and Horror #14 (editors, Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling), and Year's Best Weird Fiction #1 (editors, Laird Barron and Michael Kelly). Thomas lives in Massachusetts.

"Other countries have conquered us over our long history, and sometimes they changed our name. Hundreds of years ago, our Emperor Tho tried to think of ways to protect his country from being attacked again, after he managed to drive out the last invaders. And he knew he had to change the name his enemies had given to his country. Then Tho had an idea… a way to keep other people from wanting to come here and steal his empire. He would hide it from their eyes, and their minds, and the eyes and minds of any demon lords who might try to bring more bad luck to his empire. So he gave our land the name it has to this day."

"And what name is that?"

"The Unnamed Country."

From Jeffrey Thomas, creator of Punktown, comes The Unnamed Country, a mosaic novel weaving tales of a land and people poised between the ancient traditions of the past and the burgeoning technology of the future. Where devils, gods, and ghosts still haunt the land, and where you may just discover a unicorn.

Fans of Punktown will be enthralled by this different side of Thomas. Ross Lockhart says, "The Unnamed Country is a collection of stories, all set in a fictionalized version of Vietnam, that coalesce into a novel-like experience, where the sum of the parts adds up to something more than the whole. I consider The Unnamed Country to be some of Jeffrey's finest work."

"A modern classic … on the level of Lafcadio Hearn or ltalo Calvino."

– GreyDogTales"Jeffrey Thomas has built a temple for you to visit, but he does not stop at the temple or even the gods for whom the temple stands. He has also realized for you the people who worship there, and the people who refuse to worship there, and the people who play video games of their gods' adventures, and the people who sell lottery tickets and unicorn horn smoothies to tourists in the shadow of that temple. You might be one of those tourists when you enter, but as with all powerful temples you won't be one by the time you leave."

– Brian Hauser, author of Memento Mori: The Fathomless ShadowsLeep was playing a computer game when his two-year-old sister Fhu Fhu was killed.

The game was based on the adventures of Cholukan, the Holy Monkey, specifically focusing on his adventures in Hell rescuing the beautiful virgin who had become his obsession. But Cholukan could return to the mortal plane at various points in the gameplay, transported with the magical help of the Gold-Scaled Dragon, and visit the pretty little hamlet where the virgin Bhi Tu lived and from whence she had been kidnapped by demons.

In this village, Leep (in the form of Cholukan) could save his game progress at a temple, buy supplies or upgrade weapons at various shops, and restore his health at an apothecary. He welcomed these stays in the village, and often prolonged them, strolling the flower-bordered lanes between simple cottages with tiled or thatched roofs, playfully chasing and scattering the ducks by the edge of the pond, talking with everyone he met on his meanderings. Leep felt more comfortable interacting with these people than he did those who lived in his own neighborhood.

Leep associated many things in his life with specific colors. He found colors sometimes held mysterious significance other people were apparently not conscious of. For instance, he strongly associated green with this little fantasy village inside the Cholukan game. Green was the color of transcendent peace.

As exciting as the game was, in Hell where it primarily took place, Leep would have been quite content if all it offered were these excursions into Bhi Tu's hamlet.

Leep's mother had asked him to watch Fhu Fhu while she cooked, so he hadn't put on his headphones as he normally would to properly immerse himself in the game. So it was that he heard a single odd squawk come from just outside. After which he heard his mother shout from the kitchen, before she began screaming outside in the little courtyard of their home.

That was when he remembered Fhu Fhu.

He jumped up from the computer desk and rushed outside in time to see his stepfather's car rolling forward, to move its rear wheel off Fhu Fhu's body. Leep's mother was pushing the back of the car, as well. When the wheel was off Fhu Fhu, Leep's mother swept the child's limp body up against her chest and turned to run back inside the house. Leep's bare-chested stepfather scrambled out of the car and raced after his wife.

Later, Leep would learn the sequence of events, for an old neighbor woman who had been sitting in front of her home had seen everything while husking ears of corn. Overhearing that her father was going to the market, Fhu Fhu had gone out to the car unbeknownst to her parents, patting at its tail end and waiting for her father to come and load her inside. But when he had slipped into the car and begun reversing it out of the courtyard, he hadn't seen his daughter behind the vehicle.

Once the whole story was filled in for him, Leep screened it like a film in his head, countless times over the months to come. Especially in the days immediately following Fhu Fhu's death it became a nearly ceaseless loop, seemingly running even when he was asleep. The film loop raised endless questions for him, such as: why hadn't his stepfather put on a shirt before going to the market? Why hadn't his stepfather thought to bring Fhu Fhu with him? Why had Leep's panicking mother carried Fhu Fhu inside the house instead of into the car, so they could bring her straight to the hospital? Not that it would have mattered, ultimately, but her actions seemed illogical to Leep. Did she see the car as untrustworthy, at that point, a thing of menace?

And mainly, for whatever reason, Leep thought about the dress Fhu Fhu had been wearing. It was a thin little dress of a bright reddish-orange color. Sunset orange. Orange. Why had his mother selected this dress specifically that morning? Was there some significance to it, some cosmic symbolism that was lost on him? When she dressed her daughter that day, his mother hadn't suspected it would be the last time (because others changed Fhu Fhu into her white funeral dress, after they had bathed her; Leep's mother was in no condition to perform these duties herself). It could have been another dress, another color, but it wasn't. So many things could have been different. But they weren't.

In an alternate system of events, Fhu Fhu could have still been alive.

When his mother rushed past Leep into their house, carrying his crushed sister, she met his eyes and shrieked, "You were supposed to be watching her! Stupid! Stupid!" She might have hit him if she weren't so preoccupied. Leep just stood there helplessly, saying nothing, feeling dream-like and disconnected. His shirtless stepfather chased after his wife, looking stricken and guilty...but as far as Leep knew, his mother never ended up accusing her husband. He had supported them ever since the death of Leep's father, who had been accidentally electrocuted working on power lines.

In the days and months that followed, Leep's mother would point at him and sob, "It should have been you killed, instead of your precious sister!"

"Now now," his stepfather would soothe his wife, now that he was assured she didn't blame him for their daughter's death, "you know the boy is crazy."

In the past, before his stepfather had come along to care for them, Leep's mother would sometimes weep in despair, "It should have been you killed, stupid child, instead of your father."

And though Leep could understand this sentiment, he himself didn't wish he had been electrocuted instead of his father – a good-humored, patient man, who had taught Leep how to use the family computer. Rather, Leep wished he and his father had been electrocuted together.

There was one man in Bhi Tu's green village who tended a vegetable garden in front of his cottage. His dialogue was minimal – just things like, "Have you talked to the monk yet? He can help you remember where you have journeyed thus far." Or simply, "Good day to you, Mr. Monkey!" Leep liked to stop and talk with this villager in particular, though, because he bore a superficial resemblance to his father.

But within hours of Fhu Fhu's death, Leep's mother tore their computer system apart, and carried the components out into the courtyard one by one, dashing them to the ground, littering the dusty pavement with broken pieces of plastic, metal, and bare electronics. The villager tending his garden still trapped inside, unseen, like a miniature genie.