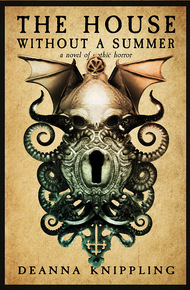

DeAnna Knippling is an eclectic bookworm who writes mystery, horror, science fiction, fantasy, romance, and classic-style pulp adventure stories with plot twists to die for! Her hobbies are cooking, taking long walks on Florida beaches, fangirling, digging into AI, open-source intelligence, history, biology, and psychology—and reading lots of fiction, graphic novels, and web comics while her tea goes cold. Author of The Witch House and The Clockwork Alice, you can find her at WonderlandPress.com.

The year is 1816, in Northamptonshire. A red, spiderwebbed haze covers the sun. Temperatures drop, fields flood and freeze, grain rots on the stem. The people are starving, and even the wealthy and titled are affected by shortages. Sickness spreads as a red fungus overtakes fields, seals over windows, and infiltrates cellars. Time itself is misaligned with the outside world—or are the strange happenings hallucinations, caused by the fungus?

On the way back from the Napoleonic Wars in France, Marcus, the younger son of the Earl of Penderbrook, returns to find his brother dead, the estate covered in fungus, and his father sinking into madness.

The last thing Marcus wants to do is be responsible for Penderbook; he wants only to spend the rest of his life playing cards, drinking, and seducing other men's wives. But even the responsible life of an heir escapes from his grasp, as his brother's body disappears, his father turns violent, and pale monsters horrify the countryside.

As Marcus pieces together the truth, he discovers a past—and a future—more tainted with evil than he could have suspected.

From the family wine cellar to the folly behind the house—from the pond where he played as a child to the new cotton mill built along the stream—

None of what happens at Penderbrook is innocent.

And the monstrosities that have been committed may still be carried in Marcus's blood…

A tale of transformation and terror, set in the year Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein.

I've long been fascinated with the year without summer. A massive volcanic eruption the year before covered the Earth in ash and dust. In the strange year that followed, many people starved, but artists created. From that strange year, we got Frankenstein and vampires, amazing poems and beautiful paintings. DeAnna Knippling uses that year to write a cross genre Gothic Regency filled with time slippage and monsters. As long as I've known DeAnna, she's let her wild imagination run free. I can't think of a better author to write a cross-genre time tale like this one. – Kristine Kathryn Rusch

"The language and mood of this book were perfectly set to pull the reader in and take them on a tense ride. It genuinely felt like I was reading a vintage story, but at a faster pace than typical. The characters were flawed and interesting, the setting and world events shaping it were intriguing, and the creepy factor and sense of "other" were up there. A dip into the uncanny, thanks to skilled writing."

– Shannon Lawrence, author of Blue Sludge Blues & Other Abominations"[This book] reads as if it was sitting on a book shelf in a home in another century long ago. This is no small feat and one to be applauded. This book could easily be tucked in next to The Turn of the Screw or The Woman in Black."

– Amazon Reviewer"This is a very thoughtful gothic horror. This is a subtle horror that creeps up on you as you read it and deeper you follow Marcus in the mystery of Penderbrook (and what happened to his brother), the more the horror feels tangible. It goes from a feeling of unsettled unease to otherworldly horror and I loved it!"

– Goodreads ReviewerHistorical Note

The year of 1816 was known as "the year without a summer." Across the world, temperatures dropped. Snows and frosts lasted until June, interspersed with heavy rain. Sunspots visible to the naked eye covered the sun. Crops rotted in the wet fields. When the fields were replanted, the crops rotted again.

Napoleon had only just been defeated. A plague of typhus spread across Europe, killing more people than the Corsican general had. Merchants bought up what stores of grain there were to be had, increasing prices. Farmers refused to sell their grain outside of their home districts. In Great Britain, what with one thing and another—including the ludicrous Corn Laws, designed to keep the prices of grain high—over a hundred thousand people died of illness and starvation. Food riots happened all across Britain and France.

To some, it was very nearly the end of the world.

The year before, the volcano Mount Tambora had erupted in what was then the Dutch East Indies. It was an eruption ten times as powerful as that of Mount Krakatoa in 1883. The Mount Tambora eruption was the most powerful one known in recorded history, at a seven on the Volcanic Explosivity Index. (Krakatoa was a six; Vesuvius and Mount St. Helens were fives.) So much gas and dust were thrown into the atmosphere that it chilled the surface of the earth for two years. Worldwide famine followed.

Painter J.M.W. Turner caught the strangely miscolored skies after the eruption. His paintings from before the tragedy, in 1814, depict skies of a cool, bluer hue; afterwards, at dawn and sunset, the skies in his paintings burned the color of blood, and in daylight hummed with an almost eerie golden light.

The light remained in its distorted colors for almost the rest of Turner's career; he died in 1851.

The summer of 1816 saw Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelly in Geneva, Switzerland, telling Gothic tales with the poet George Gordon, Lord Byron, and the doctor John Polidori. The rains kept them indoors most of that summer. Mary Shelly's ghost story was that of a resurrected man, and the mad doctor who brings the creature back from the dead: thus, Frankenstein was born. It also saw author Jane Austen beginning to sicken and fade from a mysterious illness, from which she died in 1817.

By September 1816, the snows had begun again. In fact, snow tinted red from volcanic ash fell in some parts Italy all throughout the year.

It was the Regency Era.

While the upper classes held their endless parties, balls, and operas, attended gambling hells, scrambled to make advantageous marriages for their daughters, and obsessed over French fashion, the lower classes rioted and starved.

Many people were convinced the world was ending.

Prologue – The Crystal Palace

It wasn't until Miss Lucy Abbott had attended the Great Exhibition of 1851 several times that she began to truly understand what had happened in the year of 1816.

Decades had passed; the unendurable, mad year of 1816 had come to a close; those who had died had faded from memory for the most part, either disappearing as if they had never lived, or taking on the aspect of the people they ought to have been, rather than the blackguards they were. In particular, the reputation of the Earl of Penderbrook had been much ameliorated.

In Lucy's secret heart of hearts, she suspected that she herself had been changed little by what had happened, although at the time she had felt herself to have been transformed entire. What she had lost seemed the world to her. But, both before the tragedy and after, she was as dark of mind and eye as ever; her heart still dwelled upon the injustices that she saw everywhere. But who might she have been, if events had occurred otherwise? A wife, a mother, and a fine addition to society—if somewhat macabre of humor and a little too interested in novels.

Until the Great Exhibition, she had supposed herself entirely recovered of her peace of mind. And indeed, the first several times she visited the Crystal Palace, home to the exhibition, she felt only wonder, sore feet, and delight.

But as the Great Exhibition progressed, her heart began to leap uncomfortably about in her chest: at the sight of certain too-familiar, yet altogether featureless faces; the smell of mildew and unwashed bodies; even the sound of a laugh, shrill yet commanding, that reminded her of the Earl's.

As she wound her way through the endless exhibits collected by Prince Albert and his committees, she was forced to remind herself more and more often that she was not walking through the halls of Penderbrook.

Penderbrook was gone as though it had never existed.

Thank God.

#

When first the Great Exhibition had opened, she had gone to see it like everyone else: it was a marvel, a wonder, the gathering of all that was brightest and best in the world, the promise of increase and prosperity to all mankind. She went because she had been invited by friends. She went because she had always had more curiosity than sense. She went because she had an idea that she would like to set one of her stories there, or at least to gather the flavor of a hundred different countries around the world, so that she might set her stories anywhere, and at least have some hope of getting something right.

She was always in despair that a reader would catch her out in some hideous inaccuracy, although they seldom did, or cared.

The Crystal Palace was a shining edifice, grand and impressive, a hall made of steel and glass. She could see inside it as the carriage approached, the sea of humanity that entered it, and, through the glass, the bustle upstairs, and an endless row of booths. She was handed out her carriage, escorted inside, and treated with all civility. She was not so overwhelmed that she did not understand that she was being treated as visiting royalty in the hopes that she would write something favorable about the exhibition for the Press.

It was everything that she had hoped for, and she promised herself that she would return again and again, and the next time she would attend with a notebook and more comfortable shoes. Later, she remembered little of her first visit but a blur.

She continued to visit the exhibition, to take copious notes, to study, to dream.

This continued into October of 1851, when the exhibition was about to close. The sense of wonder still remained, but it was a frantic sort of emotion now, the kind of feeling that one gets when one stays up past one's bedtime and had drunk just enough brandy to feel a certain amount of strain underneath one's own merriment.

It was a twilight sort of mood.

The exhibits, over the course of the exhibition, became less and less well maintained. The upper tiers of British society began to absent themselves, and the exhibition put on specials for the lower classes to attend more cheaply. The halls were more packed than ever. Little things began to disappear, either stolen by thieves or preventatively removed by the owners, wary of thievery.

She began to feel a certain familiarity, not of the exhibition itself, but of some other place, which she could hardly remember.

Then one day she turned in the hallway around one booth to the next and did not recognize where she was. She was surrounded by pale figures rushing past her, not quite ghosts, but men and women with all the color washed out of their faces, as though they were illustrations printed on onionskin paper. They grimaced at her and at each other, baring their teeth. Her skin rose up in instant gooseflesh, and her teeth chattered against each other several times, shivering, before she clenched them together.

When she glanced back over her shoulder, the hall seemed familiar again. There was the new steam engine; there was the new type of lock that everyone had been so certain of no-one ever being able to pick! But of course it had been defeated by an American locksmith in a matter of days… In other words, she knew her ground. The phantoms had vanished, or rather been subsumed back into the people surrounding her, who seemed as perfectly ordinary as always.

But upon walking forwards a few steps, she shuddered again.

Penderbrook.

As the word came to her, she jumped back from a pale-faced gentleman who had come forwards to shake her hand. She had no wish to startle the man—he wished only to tell her that he enjoyed her stories—so she forced a laugh and quipped, "You made me think of my editor for a moment!" He laughed, and they chatted briefly.

She hoped that she had concealed her true emotions from appearing on her face.

At any moment, she expected to be snatched from behind, a cold limb twining itself about her shoulders.

Lucy…

You know you must leave, Lucy, before it is too late.

After her admirer had excused himself, she had been solicitously asked by her secretary if she wished him to find her a seat; she had gone quite pale. She clutched his arm, saying that she felt a bit dizzy and did not wish him to leave her side, lest she fall.

Do not let me vanish.

It had long seemed to her that she owed a debt to Penderbrook. Or perhaps debt was not the right word. But there was a part of her which belonged to Penderbrook, which she had always suspected would someday be reclaimed as its own.

Her secretary held his arm stiffly at his side, and she clung to it, near to weeping. The halls seemed to spiral about her, wrapping her tighter and tighter until her breath became painful in her chest. The sense of being pulled or called increased. The faces spinning past her seemed to leer at each other, every face turned into a kind of translucent, bloodless clay.

This place is dying, she realized.

The Crystal Palace was clinging to life as a drowning man might cling over-tightly to his would-be savior, causing them both to sink.

As Penderbrook had done.

And she, of all who were present, was perhaps the only one to understand the sensation, because she had felt it before.

She must not let it take her; she must not let it take her secretary. She would linger no longer.

Slowly, carefully, deliberately, she took a step forwards. The Crystal Palace pulled at her. Oh, how it pulled! Like softness, like warmth, like the stupor after lovemaking, like candlelight. But she knew what it was now, knew that it was only winding up its cocoon, tighter and tighter, seeking a place of safety and finding only self-destruction.

Lucy…

You must leave, Lucy, before it is too late…

Her secretary stopped her to ask, "Miss Abbott? Are you quite all right?"

"I have a desperate need of air," she told him, and he led her outside of the Crystal Palace, to which she never again returned.

The building was pulled down soon after. They said it was to be rebuilt on the top of Sydenham Hill, to hold permanent exhibits.

But it was not the same place, and she ever after felt herself having very narrowly escaped indeed.