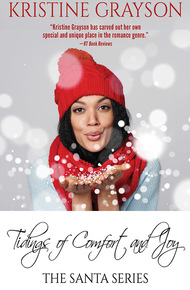

Called "The Reigning Queen of Paranormal Romance" by Best Reviews, bestselling author Kristine Grayson has made a name for herself publishing light, slightly off-skew romance novels about Greek Gods, fairy tale characters, and the modern world.

She also contemporary romance under her real name—USA Today bestselling author Kristine Kathryn Rusch.

As Kristine Grayson, she also edits the romance volumes of Fiction River: An Original Anthology Magazine.

For more information about her work, go to the Kristine Grayson website and sign up for her newsletter.

Dallas Demaris unites magic with technology. She specializes in computers. But when her company orders her to go to the North Pole to help Claus & Company fix their outmoded computer system, she goes grudgingly.

Dallas hates how Santa runs his business, and she tells everyone, including Lothario Johanssen, the handsome man who invented the machine that runs the North Pole.

Lothario dedicates his long life to the machine. He knows the system better than anyone—including Dallas.

But what if Dallas discovers something that Lothario missed? Can they find a way to work together to fix the critical machine before December, before its malfunction ruins Christmas for millions of children?

Kristine Grayson once again brings romance and fantasy together as only she can do.

"Grayson's clever, humor-tinged writing is absolutely delightful."

– Booklist"Kristine Grayson gives 'happily ever after' her own unique twist!"

– Kasey MichaelsOne

The first thing Dallas Demaris would have told anyone who asked was that she loved the office building. Really, really loved it. Set on a cliff overlooking the ocean in Malibu, California, the office building had everything she had ever wanted in a work space. It had:

•Floor-to-ceiling windows everywhere, to soak in the sunlight and maximize the views.

•The view, which was of:

The ocean—and not some gray, scary, violent, cold ocean, but the ocean the way it should look, all blue and sparkly and inviting.

The sky—which was generally blue and sparkly and inviting as well.

The beach—which was pristine (except where it wasn't), and if she squinted just a bit (past the ships and the outlines of oil rigs) she could almost imagine the world as it once was, all pretty and ready…to be ruined by human beings.

•A soft carpet, which enabled her to stand and look at the view for a long period of time.

In truth, the office was beautifully designed, with workspaces that flowed. Each workspace had its windows. Even the corridors had views. Whenever she stepped off the elevator (which, sadly, did not have views), she was greeted by a bank of windows, revealing some part of the Southern California coastline.

The entire working part of the building faced westward. The rest of the building was built into that cliff face, and the storage parts of the building were the ones on the cliff-face side.

Presciently, the building was made of concrete so even when the scary wildfires scraped across Malibu—and they did, far too often for her taste—the office would survive or would have survived, even if it hadn't had magical protection, which it did.

It also had been retrofitted for earthquake protection, by the mortals who were following mortal law, which simply made the building safer through a non-magical event. The building had always been protected against a real earthquake, but mortals didn't recognize magical protections, hence the retrofitting.

Mortals also didn't realize what this building was, and that was by design. Most people saw a rectangular gray and glass building rising out of the cliff face, thinking the office was just another wealthy person's home or big company's monument to excess, instead of a working office, filled with mostly disgruntled employees who, for some odd reason, would rather have been elsewhere.

Dallas didn't want to be anywhere else for any reason. She loved the warmth. She loved the sunshine. She loved the beach, the ocean, and even those tinder-dry mountains behind that cliff.

She had been lucky enough to score (an exceedingly expensive) rental nearby, but even back in the days when she had to drive to work, she didn't mind the traffic in the greater Los Angeles area. She figured it and the smog and the congestion were a small price to pay for getting to work in one of the prettiest places she had ever seen.

The second thing Dallas would have told anyone who asked (and really, no one ever did) was that she loved the work. She'd been doing it for nearly two hundred years now, trying to make machines compatible with magic, and when that didn't work, inventing machines that were. She had a knack for making devices bow to her whims.

It had taken her a greater part of the last century to figure out how to make magic and computers compatible, but she had done the deed well enough that most of the magical could now carry cell phones without having them explode on a daily basis.

Sure, she wasn't able to make magic and tech completely compatible—not mortal non-magical tech—but she could invent tech that had magic as its base.

Her brain was filled with fiddly little details of all kinds of science and magical history, waiting for each fiddly little detail to serve its purpose in the grander scheme of things. She wasn't sure what that grand scheme was, but she knew—deep down—that she was part of that grand scheme.

And one day, she would figure out how, exactly, she fit in.

But—and anyone who was paying attention would know that there was a but coming, wouldn't they?—her job wasn't ideal. She was the only woman who worked in the office, not because she was the only woman who could combine tech with magic, but because she was the only woman who had actually bullied her way into this place.

Or rather, obliviously barged her way in. Because Dallas obliviously barged her way into a lot of success over the centuries. She simply didn't take no for an answer. She also refused to believe that her brain was inferior to anyone else's—man, woman, transgender, standard magical creature, non-standard magical creature, or something brand-spankin' new.

And since she took that attitude toward life, she figured most of the pushback she got on the things she did was because she was brilliant and ahead of the curve, rather than because she was a woman.

Although today, standing inside the corporate meeting room of the office, it was hard to ignore the fact that she was being chosen for this new job not because she was the best person for the job, but because she was a woman—or rather the woman—and the men who ran the place wanted her the hell out of here.

The men who ran the place had been in charge for a Very Long Time. Before the office was built into this cliff face sometime in the last century. Those men—and there were a dozen of them—weren't in Malibu because they loved it. They still considered Malibu a backwater of the first order, since all but two of them were European.

In truth, they couldn't get more out of touch. The director, Waldo Ranklesworth, flew home to England every evening. Literally flew. He didn't like to spend any more time in the Colonies, as he put it, than he had to.

Ranklesworth was round. His face was round, his torso was round, and his stubby little legs were round(ish). He had had a mustache since the nineteenth century, and it had finally turned white to match his thick head of hair. That mustache had either dug deep grooves into his jowls or had forced his skin into jowls—Dallas couldn't really tell. His bushy eyebrows sometimes brushed against his eyelashes, creating a tangle that he had to rub away like a child rubbing sleep out of his eyes.

Dallas had had trouble taking Ranklesworth seriously from the moment she met him. His pinched tone and his accent, liberally borrowed from Oxford but not of Oxford, didn't help.

He tended to hire men similar to him, following the mandate of the company, which was that most Western languages and cultures be represented. He wouldn't have been able to handle the office if it had to handle Asian cultures, African cultures, and Middle Eastern cultures. He had been heard to argue that the Eastern European cultures weren't really European at all.

If Dallas were militant—and she wasn't, not really, because it interfered with her work—she would have been some kind of whistleblower. Although she was never entirely sure who Ranklesworth actually worked for, or what the hierarchy of the office was once you got outside of this particular building.

Dallas had always been happy to do the almost-impossible assignments the men around the table had given her, because she liked a challenge. When she first started here, before there were even roads heading to the beach, she had believed the men gave her the biggest challenges because she had the biggest brain.

Slowly, she realized, they had given her the biggest challenges because they couldn't figure out any other way to get rid of her.

And really, it was the other men at the table who had taught her that. Not the ten Ranklesworth clones, who all had varying degrees of roundness, mustachedness, and thick-white-hairedness, but the rotating seats of the two Americans.

At first, those two men were also round and mustachioed and white-haired (one illegitimately, using magic to make his bald pate look just like Ranklesworth's head). Those two men had both come from the East Coast, from "good" families, and got tired of Ranklesworth's snobbery, moving on and up, as the men liked to say.

But then orders came from on high for some diversity in the office, and that at first meant men from the Middle West and California itself, not that it worked out for them either. And then the 1960s happened, and diversity took on a new meaning, and so did the levels of passive-aggressive viciousness. The two American seats usually went to a man of color, who would get angry at The Way Things Were Done, and would usually try to recruit Dallas to help foment some rebellion, and she would beg off, usually because she had the latest interesting job, and the rebellious Americans would move on, for reasons she never entirely understood. (Except she knew that they hadn't been fired.)

She put up with the passive-aggressive bigotry, and the frosty tones, and the arch comments about everything from her gender to her accent to her clothing, because she loved the work, although she had to admit that she had come to dread finishing the latest task, because that would mean another meeting with Ranklesworth and his team.

This meeting was no different. She knew that she wouldn't be praised for proving yet another impossible task to be possible, but she would like Ranklesworth and his team to at least put a chair at the table for her, so she wouldn't stand like an angular, overly tall, badly cast supplicant out of a high school production of Oliver!

Because that was another of the problems. In addition to being the only female mage in the building, she was also the tallest, thinnest person here. Six-two when she was barefoot, taller when she wore her favorite pair of leather-tooled cowboy boots, she was also the only person who still had actual color in her hair.

And that color happened to be a rich, dark amber—not flaming red, really, but not brown either. One of those colors that women usually bought out of a bottle. Dallas never messed with it, not even as strange hair colors like hot pink and green came into vogue. She usually wore her hair pulled away from her face, although today, she let it down, because something about these meetings made her want to seem more female rather than less.

Her eyes were that same amber and her skin wasn't much lighter. If someone had done a genetic test of her past, they would have found every single category of Texan in her DNA—from Comanche to Spanish to Mexican to white. She hadn't lived in Texas in more than a hundred and fifty years, but she carried it with her, in her dress (she favored bolo ties when forced to wear a tie), her accent, and her DNA.

She clearly did not fit in, and she wasn't quite sure why the men hadn't told her that from the beginning. She liked to think it was because they were stunned by her presence—an uppity woman of uncertain background who could outperform them on every single task. They kept trying to best her, and they never could.

One of the Americans hired a few decades ago told her they kept her because she ticked every diversity box. And she had raised her eyebrows at him: When you can solve problems as easily as I can, she had said, I will accept your theory.

He had been gone long before that theory could ever be tested.

Still, as the world changed around her, she wondered why she stayed here. Maybe there was a bit of ego involved for her as well. She liked besting the bigots. She liked proving to them over and over and over again that she was the best at what they all did, and that they could never find a job that was impossible for her to do.

Although this new job had an odd feel, right from the beginning.

First, the men were laughing as she came through the door. The nine Ranklesworth clones had a rather gusty way of laughing, all nose and closed-mouth hilarity. The two Americans (as she still called them, even though she really should have used their names) actually giggled, which wasn't really a good look on them when they were trying to be as fusty as their colleagues.

They were holding green-and-red folders that looked out of place three days before the beginning of the Fourth of July holiday (Ranklesworth insisted on celebrating every holiday, even when the holiday celebrated his country's defeat). She had a feeling that the men thought that this time—this time—they had finally found the project that would defeat her.

Since they thought that every single time they brought her a project, and she always proved that she was more capable than they thought, they shouldn't have been so mirthful. And they usually weren't. They usually watched her with beady-eyed uncertainty, trying to figure out if they had found the right project to get her out of the company.

This time, though. This time, they seemed certain of it.

She clomped into the room, her boot heels slapping on the polished concrete floor. She had long ago stopped asking that another chair be brought into the room. Instead, she stood, towering over them as if she were the one running the meeting.

On this day, she had chosen to wear a rather flirty, sky-blue skirt, with ruffles along the hem, and a sedate ivory blouse over it. That blue skirt said female in ways she couldn't, and that ivory blouse showed off not just the assets that Ranklesworth had once commented on (inappropriately, but before the mortal laws changed to disallow that sort of thing), but the assets that she was actually proud of—her toned arms and her surprisingly narrow waist. (Surprising to her, because she loved to eat. So she would enjoy the narrow as long as she could maintain it—without magic.)

The laughing stopped when she stopped at the head of the table—or rather, the foot of the table, since Ranklesworth was directly across from her.

Half of the Ranklesworth clones looked at her as if they had never seen her before, and the other half looked at her as if they couldn't wait to see her brought down. The two Americans had stopped giggling, and weren't looking at her at all. They were examining those strange red-and-green file folders.

"Well, nice of you to join us, Miss Demaris," Ranklesworth said, with an emphasis on the Miss. He hated calling her by her last name, something she had insisted upon during their very first meeting, more than 100 years ago.

Mr. Ranklesworth, she had said primly, I do hope you run this office in a professional manner. I expect to be addressed the way you'd address any other colleague, with an honorific, instead of using my given name. Unless this company uses everyone's given name…?

He had flushed, but had called her Miss Demaris ever since. With an emphasis on the Miss to let the others know that she was female, yes, and also unmarried, which, apparently, he found to be as irregular as her female status.

His tone on this day implied that she was late, which she was not. The meeting was scheduled for the top of the hour, which was still five minutes away. For decades, he had played this passive-aggressive game with her of letting her know the incorrect time for a meeting. He had always done the same with the Americans, but on this day, apparently, they had gotten the right memo.

She had stopped worrying about it. Mr. Ranklesworth couldn't fire her, much to his chagrin, since the company had deemed her one of the most important employees it had ever had. She had had that designation since the dawn of the combustion engine, and it had only become more important in the years since she solved the computer and handheld device problems.

The company had called her to their London office just once, and there, a wizened little man who actually looked like a wizard should look had offered her the job of Director—Ranklesworth's job—but she had declined. She knew that she wasn't good at bossing people about. She was much better at making sure machines and magic worked well together, and she had said so.

The wizened little man—whose name she was not allowed to know—had nodded, and had tried to grin, even though his grin got lost in the folds of his face.

Ranklesworth is jealous of you, and will do anything to get rid of you, the wizened little man said. Rest assured that will never happen. But you will be subject to his whims if you don't replace him in the job.

She thought she could handle the whims. After all, she had been handling them for more than a century now.

But occasionally, they grew tiring. Like today.

"This is our new job," Ranklesworth said, waving the red-and-green folder. "The command comes from on high. I tried to turn the work down, but wasn't allowed to. We are stuck with this project—or rather, you are, since you're our go-to gal."

She didn't wince when he said that. He'd adopted it over the last fifty years, and it still grated. It sounded like he was making fun of her accent and her gender whenever he said it. (And her competence. Always her competence.)

"May I have a folder?" she asked as she swiped a folder out of the hands of the nearest Ranklesworth clone. They were conveniently one folder short, which was a stupid trick they had played more often than she cared to think about.

The folder was thick with materials. All of the jobs arrived in the office on paper. She had arranged a way to get email and had a computer that could print out anything the group needed, but no one ever asked. The entire company preferred to use old-fashioned delivery services to deliver jobs in black embossed British letter-sized boxes embossed with gold foil.

She found those pretty a century ago, quaint sixty years ago, and tiresomely stuck in the past now.

An embossed candy cane was printed in the lower right hand corner of the front of the folder. There were no other words on the front at all.

She opened the interior, and some red, white, silver, and green sparkles plumed out, accompanied by a cheerful little tinkle of music, as if she were in a cartoon and she had just received a magical gift.

She sighed, and hoped she wouldn't be tainted by any unwanted magic. She would have to check later.

The first page floated upward and created a lovely snow-filled scene, slightly larger than the folder itself. The scene included one of those fluffy snowfalls that everyone (except her) agreed was the perfect snowfall—big fat flakes that floated lazily down and landed on snowdrifts as if directed there by some algorithm.

Shoved deep in the snowdrifts were gigantic candy canes that served as some kind of gate, and beyond it, barely visible through the lovely snowfall, were the words Claus & Company.

She closed the folder on the image. It vanished, leaving the crisp scent of new-fallen snow behind.

"What is this?" she asked, even though she had a hunch she knew. They had brought her jobs like this before, in which she had lost half a productive day watching some advertising gimmick, instead of learning what the job was. Those gimmicks always put her behind.

"You," Ranklesworth said in a tone even more plummy than usual, "are going to the North Pole."

She let out half a laugh and set the folder on the table. "Yeah, sure. Let's cut through the hazing, and get to the actual job, shall we?"

The two Ranklesworth clones sitting closest to him started to snicker. That wasn't a good sign.

"That is the actual job," Ranklesworth said, his lips puckered ever so slightly, as if he was trying to hold back an uncharacteristic smile. "You are going to the North Pole to fix their computer system."

"The North Pole," she said. "The geographic North Pole? The one with the constantly shifting ice that makes it impossible to live there?"

Ranklesworth let out a noise that sounded suspiciously like a raspberry. He was too dignified to release an actual raspberry, wasn't he? And wasn't a raspberry an American sound of disgust, not a British one?

"For the sake of the magical universe," he said when he got his puckered lips under control, "I would never send anyone to the—what did you call it? The 'geographic North Pole.' That's as uninteresting to me as the 'real' Mount Olympus. No, Miss Demaris. I am sending you to the actual North Pole. Santa's North Pole. I want you to fix his computer system."

"Santa isn't real," she said, and everyone in the entire room swung their heads toward her as if she had just said that magic wasn't real.

"I assure you," Ranklesworth said, "Santa is real."

"Well," Dallas said, "if he is real, I have issues with working for him. He allows children to go to sleep in need every night. He doesn't give out gifts to a goodly portion of the world. And he seems to favor the wealthy over everyone else."

"I don't really care what your political beliefs are, Miss Demaris," Ranklesworth said. "The fact is that his computer system is malfunctioning and he needs a magical/machine tech. I must tell you that all of the Christmas holiday is on our shoulders here. If we fail—well, if you fail—no child will get a visit from Santa Claus this year."

The laughter had left the room. The men were all staring at her nervously. And if Ranklesworth was telling the truth, then this might actually be a job that could get her fired if she failed.

"No," Dallas said.

"No?" Ranklesworth asked.

She nodded. "No," she repeated.

"No what?" he asked.

"No, I will not take this job. I despise snow and cold. I refuse to go anywhere that has candy canes for gates, and I want nothing to do with this Claus & Company."

Ranklesworth let out a gusty sigh. His bushy eyebrows rose into his messy hair and, for once, his mustache actually looked like it was the right length.

"Well," he said, "I'm afraid you don't get to say no."

"Why not?" she asked. "I have never turned down a job before. In more than a century, I've done exactly what you've asked."

Even when it was stupid. Even when it was designed to make me fail. She thought that part, but didn't say any of it.

"Because this order didn't come from me." Ranklesworth's beady little eyes met hers. "It came from my boss."

"Tell him no," she said. "Or I will."

Ranklesworth closed his eyes for a moment, and she could almost read the thought balloon over his head: Save me from uncooperative females. Or something a bit harsher, something she didn't exactly want to see.

Ranklesworth took a deep breath, opened his eyes, and then said, "He asked for you by name. He said you are the very best person for the job."

"This job?" she asked, surprised. Ranklesworth had given her a reluctant compliment.

"Any job, really," Ranklesworth said tiredly. He clearly did not want to admit that. "You do have a higher success rate than anyone in the company."

She inclined her head toward him. Ranklesworth had never acknowledged that before.

The Ranklesworth clones were looking at him in shock. The Americans were looking at her in shock.

She wasn't sure exactly how to respond, so she didn't say anything.

"But yes, this job," Ranklesworth said. "He would say it was impossible, but he knows you've done the impossible before."

"Oh, for god's sake," she said. She had done the impossible. She took pride in the impossible. But she didn't want to do this. She didn't want this job at all.

It was the very first job they had ever told her to take that she was declining. And she was going to decline it forcefully, by giving Ranklesworth what he always wanted.

She took a deep breath, and said, "I'll quit before I go up there."

The clones' heads swiveled toward her. A few of the clones grinned at her, as if they had finally won a big prize. The Americans looked panicked.

Ranklesworth rolled his eyes. His lips thinned and then he shook his head, as if he couldn't believe what he had just heard.

"Much as I would love to accept your resignation," Ranklesworth said, "it's not possible here."

The clones' heads swiveled again, now looking at him in shock. The Americans frowned at him.

She did too. Ranklesworth should have jumped at the chance to get rid of her.

She braced the fingers of one hand against the cool wood of the conference table, feeling a bit breathless. They wouldn't let her quit? She had always kept that in her back pocket, just in case they stopped giving her interesting work.

That was the thing Ranklesworth never understood: he wasn't ever going to get rid of Dallas if he continued to give her impossible tasks. He would have gotten rid of her decades ago if he relegated her to a desk and treated her like the clones.

Although, this particular impossible job was getting rid of her, wasn't it? Even though, Ranklesworth said that wasn't possible.

"You've wanted to get rid of me for decades," she said.

Ranklesworth raised those bushy eyebrows, as if her comment had surprised him. It probably had. Not because he wanted to get rid of her, but because she knew about it.

"Accept my resignation, and send one of these gentlemen to the North Pole," she said.

One of the Americans actually turned his chair slightly, as if he was trying to get Ranklesworth's attention, but knew better than to interrupt.

"Can't," Ranklesworth said. "This is some kind of magical emergency, an all-hands-on-deck sort of thing. You'd be drafted even if you quit. It is, I'm told, the case of having the right person in the right job."

He sounded sincere, but she had no idea if he really was. She might have believed him if he had supported her work in the past. But he hadn't, and if she went by personal experience alone, she had to assume this was some kind of game, cleverly designed to make her the loser.

"I think I'll go to London and talk to your boss," she said. That man was the wizened little man she had met once before. He had seemed to like her, even if there were so many rules around his august personage that she half-felt like she had visited some kind of royalty.

Negotiating rules like that made her nervous, but she would do it in this instance.

"Do so," Ranklesworth said. "But bring warm clothing. They might just send you north straightaway from the London offices."

She frowned. That sounded true too. She'd actually seen it happen before. The previous Americans had gone to complain about something and never returned. They had been sent elsewhere, straight away from the London offices.

That could happen to her, even if London didn't send her to the North Pole. She might never return to Malibu, to her beach and her sky and her ocean.

That might just break her heart.

The others were quiet. The Americans were looking down, as if they were embarrassed or worried.

"Why aren't any of you fighting for this job?" she asked. She'd seen that before on the really important ones.

"Santa has a reputation," Ranklesworth said. "It's not a good one."

"Yeah, I noticed," she said.

"Not for the reasons you mentioned," Ranklesworth said. "But because he's…um…notoriously difficult for mages to work with."

"He doesn't like us much," one of the Americans said to the tabletop.

"Then why are we helping him?" Dallas asked.

"Because the magical underpinning of the universe is at stake," Ranklesworth said, as if she were the dumbest person on Earth.

That tone, she recognized. She had heard it in almost every conversation she'd had with Ranklesworth, particularly when it dealt with the way that mages and the so-called real world interacted.

She didn't ask, What did I miss? because that question put her in a one-down position. But she didn't exactly know how to ask what she needed to ask, so she settled on a good old American standby.

"Huh?" she asked.

Heads swiveled, except for the Americans. One continued to look down. The other put the back of his fingers against his forehead, shielding his face from everything going on at the table, the way that kids sometimes did when they were trying to become invisible.

"You really don't know this?" Ranklesworth asked. Then he shook his head, and repeated more to himself than to her, "You really don't know this."

He sighed gustily, shook his head again, and said, "Belief in magic powers magic."

Her eyes narrowed. She knew that. Of course she knew that. That was why some of the older so-called gods had less power than some of the other so-called gods. Why certain cultures thrived in certain environments, like the Faerie Kings in Las Vegas. There, the irrational belief in luck powered most of their magical devices.

Dallas had used that luck-belief once, on a job that had taken her in the bowels beneath the city, to an astonishing and crazy Faerie King casino that had literally made her head spin.

But she knew better than to remind Ranklesworth that she couldn't do her job if she didn't understand what added fuel to magic's fire.

"Millions and millions of children believe in Santa Claus," Ranklesworth told her. "For each child that ages out of the belief, another is born into the belief. The mortal culture perpetuates that belief and is complicit in making sure that children under the age of five or so all believe it."

"They don't all believe it," she said unable to keep silent. "The 'culture,' as you call it, is at best what you used to call Western culture, at worst a purely American branding episode that focuses on children raised in a Christian—"

"Really," Ranklesworth said, "I told you, no politics."

"It's not politics," she said. "It's fact—"

"I don't care," Ranklesworth said. "It's a job that we have to do."

"Then find someone else. Because I refuse." She slammed the folder on the table and walked out of the conference room, not even stopping to look at her lovely ocean.

Ranklesworth could deal with his bosses.

Because she was done.