Eugen Bacon is an African Australian author. She's a British Fantasy and Foreword Indies Award winner, a twice World Fantasy Award finalist, and a finalist in the Shirley Jackson, Philip K. Dick Award, Kate Wilhelm Solstice Award and the Nommo Awards for speculative fiction by Africans. Eugen is an Otherwise Fellow, and was also announced in the honor list for 'doing exciting work in gender and speculative fiction'. Danged Black Thing made the Otherwise Award Honor List as a 'sharp collection of Afro-Surrealist work'. Visit her at eugenbacon.com.

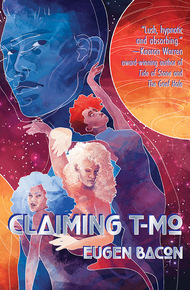

In this lush interplanetary tale, an immortal priest flouts the conventions of a matriarchal society by choosing a name for his child. The act initiates chaos that splits the boy in two, unleashing a Jekyll-and-Hyde child upon the universe: named T-Mo by his mother and Odysseus by his father. The story unfolds through the eyes of these three distinctive women: Silhouette, Salem and Myra - mother, wife, and daughter. As they struggle to confront their fears and navigate the treacherous paths to love and accept T-Mo/Odysseus and themselves, the darkness in Odysseus urges them to unbearable choices that threaten their very existence.

"This debut novel by African Australian author Eugen Bacon is an instantly confounding and mysterious tour de force of imagination. On the surface, it's a richly textured, multidimensional tale that blends science fiction and an intricate mythology of its own making. Dig deeper, and it's a puzzle that requires considerable assembly, piece by piece, as Bacon's vision of outer-space sociopolitics, Afrofuturist metaphysics, and familial bonds comes into sharper focus. It's an audacious book, one that zooms from the broadest of cosmic conceits into the most intimate of emotional epiphanies. Bacon is not remotely interested in following any threadbare formulas of science fiction or fantasy — much toClaiming T-Mo's benefit."

– NPR, Jason Heller"Claiming T-Mo is literate, imaginative, and provocative—a strong, even unforgettable, science fiction debut."

– Foreword Reviews"Bacon employs elegant and poetic language that pulls readers into each different world and experience as felt by the three leading women. Recommended reading for those with an interest in sf, expressive language, and stories that focus onwomen's relationships and perspectives."

– Library Journal"Bacon explores a four-generation alien family saga in this gleeful, wacky debut."

– Publishers Weekly"Recommended for those looking for speculative fiction centered around Black characters as well as fiction that blurs the boundaries between genres."

– Booklist"Recommended for those looking for speculative fiction centered around Black characters as well as fiction that blurs the boundaries between genres."

a1T-Mo happened exactly one week after the puzzle-piece woman with fifty-cent eyes.

One night, black as misery, Salem Drew stood, arms wrapped about herself, at the bus depot three streets from the IGA where she worked late shifts. A bunch of commuters had just clambered onto a number 146 for Carnegie, and Salem found herself alone at the depot.

She waited for a night express bus to take her back to a cheerless home that housed equally cheerless parents. An easy wind around her was just as dreary, foggy as lunacy. There, just then, the shadow of a woman's face jumped into her vision.

Salem blinked. Was the woman real or a figment of thought? Singular parts of her were easy to file, were possibly real: maroon hair, rugged skin the color of coffee beans. And the scar... But all put together, cohesion was lost.

The puzzle-piece woman stood head lowered, quiet in the mist. When she raised her face, silver shimmered from one good eye, petite and round as a fifty-cent coin. The other eye was broken, feasibly some bygone injury. Even though it was as smooth and flawlessly round as the right eye, it held no sight. The coin perfection of its shape was embedded in scar tissue, a disfigurement that needed nothing but a single glance to seal the hideousness of it.

If Salem thought to speak, to ask, "Who are you? How long have you been standing there, watching me, and why?" the mighty keenness of the woman's good telescopic eye, the one that filtered, turned inward, then came back at her without translation, threw it right out of Salem's mind.

Thunder like the hammering of a thousand hooves did it. Salem ran without a scream, all the way through all that night, never minding the night bus when it whooshed past. All she minded was the gobbling eye, and the unwarned sound of deep belly laughter that chased behind.

2

Freedom and beyond. That was where T-Mo took Salem. He foisted himself into her life, waltzed her straight to liberty.

There is a magical quality about a man who steps through locked doors, unbroken walls. One minute he stood outside her window, next he was beside her in front of a projector show on the wall, one calm hand stretched along the back of her seat.

They were watching Part I of A Moment with God, Salem's parents' idea of an unchaperoned date, inside a cul-de-sac chalet that held no sink or toilet, not even a tacky kitchen. It stood three meters from the back door of the main building, close enough for a parent to sniff out trouble. That was the little servant room the pastor had sublet to his daughter.

Even though they had been going out some time now, Salem's temple fluttered, as did the veins in her neck. Her gaze wavered each time it met his, all through Part II of the monologue on the wall. She shifted on the couch to create distance from his reckless hand. So disoriented was she, it took awhile before she noticed the tape reel still rolled but showed nothing except snow lines on the darkened wall. Somehow T-Mo had managed to maneuver himself within inches of her skin.

"Life-forms," he said.

She jumped. "What?"

"Do you not wonder what else exists in the universe?"

She stuttered. "W-what sort of existence?"

"Complex. Minds beyond human. Do you not wonder?"

"N-no."

"But I do." He held her gaze. "And I am."

"W-what?"she said, part in trepidation of never being able to understand him, the rest in misery that at this point she really didn't.

"Complex." He reclined. "Do you not wonder," his voice drawled, "how molecular composition tolerates teleporting?"

"Teleporting?"

"See me walk through that door?"

"N-no."

"Well, then."

She blinked, studied him anew. The man whose eyes were full of space when they were not holding something wild. They were chameleon, shifting appearance with light, as did the color of his skin.

Sometimes he seemed quite tanned, sometimes tan lifted to gray. The first time she saw him, she was sure it was an ailment. How creased, so youthful a face: it had to be a disorder. The disorder soon became art under her study. The more she analyzed its pattern, the weaves and crossings of the cells on it, the more it confounded her.

Salem wasn't sure at first what it was that drew her to him, because he wore the same fossil skin then. She was nineteen, he looked forty. But the jazz in his eyes made her whimsical. She wondered about this man of darkness and light who yet felt more natural than wind. How did he measure up to her father's barometer?

She knew that choices needed to be made. She could never go back to Milk is Available Here. Not the IGA again. Never.

3

Salem was a little turtle locked up in its shell, before T-Mo. Her parents conversed with her on a need-to-know basis. Her mother had stormed out of Nana Modesty's womb the very night of a Christmas pageant to earn the name Pageant. Her father... she could think of no other name that suited him better. No one set eyes upon his righteous face and felt no need to go: Ike! He was a militant man, raised her so.

Both parents were immigrants, second or third cousins to each other but singly raised in spartan households by Salem's equally migrant grandparents, Modesty and Roam. Ike and Pageant found themselves tossed together in a flight to freedom, thousands of miles on foot as refugees, an army of them, sometimes fearful, often cold, always hungry. Fleeing war from a troubled country. Soon as they found peaceable settlement in a place called East Point, Ike clasped a hat in his fist and told, not asked, Pageant to be the mother of his babies. "Marry you?" she said. "Yes," he said.

Growing up, Salem nurtured dreams of abandoning her parents. Walk, trot, run—anything to take her to a place far enough that her parents could never find her. In her dreams she did trains, streets, park benches, dumpsters. In real life her ventures outside the house were the dentist, the library, the church.

The only moments she found recreation were when Pastor Ike shared his congregation with a visitor reverend. Like Bennetts Brooke. Reverend Brooke was a wired little fellow with mouth and bounce. His voice thundered, his feet danced. He bobbed at the pulpit, tossed knees and elbows, and boomed his voice at the faithful through a wireless microphone: "Who, Lord?"

"Us!" the brethren cried.

"Who, Lord!"

"Us, Lord!"

"Who did Bless His Holy Name choose?"

"Us!"

"He loves you," pointing at a woman in the front row.

"Yes, Lord."

"And you, and you, and you."

"Oh yes. Lord, oh Lord."

His eyes went intimate or wild to hush or animate the brethren. "This," he cried, holding the crucified savior on his timber cross, raising the wretched savior to face the faithful. "This"—a whisper now—"is the completeness of His Love."

"Mercy."

"Hear us, Lord."

"Amen."

The pastor's eye fell upon her. "Amen," he whispered. "Amen," he shouted.

"Amen," she whispered.

Beside Salem, Pageant shook. Her eyes were closed in fervor, quite unusual for a most unemotional woman. "Yes Lord," she whispered, over and over, moments before she fell convulsing from the pew. Reverend Brooke held his cross on her convulsing self, held and held it, even as the choir burst into song:

Come Thou Holy Spirit,

Holy, Holy, Infinite,

Come Thou Power and Peace,

Oh Ye Seraphim

Oh Ye Blessed Light

Come Thou Holy Spirit.

Come.

"Amen," said the reverend. "Amen," repeatedly. Held and held the cross as, around the church, people spread their hands and began to speak in tongues:

Ahmm-bralla-gaither-malu-theologa-umber-trivo!

Pla-ci-te-reciter-spiriniu-printa-go!

Salem, thrilled and curious, watched as the reverend held and held that cross on her mother's chest until Pageant came to and, meek as a person hypnotized, took the reverend's hand that steered her back to the pew. The choir chimed a lustful chorus from page 37 (b) of the hymnbook:

Sing to the mountains.

Lift your hearts!

Pageant's palm was sweaty when Salem slipped her hand into it. Somewhere in the back of the church, commotion as another of the brethren had the shakes. Somewhere to her right, a little child was asking his mother why she was "crying in God's garden."

To Salem, it was the best day ever, an occasion. Marked the turning point from lack of adventure to escapades in the church. Outside church, Salem watched people come and go. Often there was tea and people brought things: lavender sandwiches, salad buns, face fingers, frost-cream scones, honeydew puffs, poppy seed muffins... and much tea and lemonade. Slowly she learnt people, understood those whose sincerity flowed easy as water, those whose charitable words reeked with malice, those who came to observe and collect gossip, those who shook hands and genuinely cared, those who collected around each other and showed brand new bags, veils, hats, gloves, jackets, neckties, anything that glittered. Some gowns had lace, others didn't. Some were ankle length, others above the knee. Some ballooned before the knee or hugged thighs or ran down tiered or straight. It was a parade which, in her modest tunic and level heels, Salem found delight in watching. She understood all kinds of folk, filtered them like a sieve.

When she grew up enough to earn the chalet at the back of the house, her distractions were mainly visitor reverends, church fetes and family bees. Her life was empty, she knew. But how to change it? There were harmless tea parties where she swallowed lemonade that looked and tasted like cough medicine, nibbled finger food that was scrumptious but meager; you put it in your mouth and it melted. There were tongue-tied girls and polished boys who never wore bad socks or a single hair out of place. But these boys knew enough of Pastor Ike Drew not to muck about with his daughter, or the daughters of his parishioners.

Secretly, Salem continued her fantasies, dreaming not just of escape but of white gold and blonde bracelets and dark knee-hugger boots, everything Pastor Ike would never tolerate his daughter wearing. But for all her fancies, she was still wrapped like a nun at the local IGA shop, nurturing runaway thoughts in a stifling hot room. No wonder her mood was not right when T-Mo happened.

• • •

She processed a pack of cigarettes at the cash register and looked up to announce the cost, and her heart went soft. He stood before her, looked at her with a careless smile that cracked something inside. A sense of imminence grabbed her in so ruthless a fashion it rendered her immobile.

"Your curls," his gaze touched her hair. "Soft as the feathers of a baby bird." That tied her tongue too. He might have touched it, her hair, or perhaps only his words touched it. He at once captured her with his impetuous nature and pulverized any restraint she might have shown, so much that the beat of her heart sped to insanity.

He glanced at the barcode reader and slipped a note from his pocket. So hypnotized was she when he moved away from the queue, she rose from her stool to follow him with her eyes. Follow him where? Away from it all, the IGA, her parents, to a place filled with radiance.

How much for a dozen? A female voice severed her entrancement and Salem turned to face her, eyes astonished still. A dozen, the woman said. How much? Salem lifted the bar of soap. "Was the price not on the shelf?" she said. She sat back on the stool, looked one more time for her man but he was gone. She turned the bar of soap until she found a barcode. Beep! the reader. "Three dollars twenty for a dozen," she said. Her hands were shaking.

Two hours later she signed off the till. She was in desolation still at not having spoken a word, not a single croak, to the man whose gaze touched. He was waiting for her at the car park opposite the IGA entrance. His gaze more than touched; it fondled.

At once she brightened. "Y-you?" The longer she looked at him the more perfect he grew.

He pointed at a crimson sign on a snowy background at the top of the IGA door. It read: Milk is Available Here.

"That true?" he said. She nodded, held helpless in his gaze. "That's true anywhere. They have to proclaim it?"

She liked him. She liked him very much.

He spread his hand, gave her that winning smile that coursed rapture through her veins. He held a careless jacket across his shoulder. His eyes indicated a soft-top parked in a slot. Its bare metal gleam dazzled her eyes. "Care for a spin?"

"Holy moly," she said in wonderment. He felt right. She didn't need to be someone else.

"First girl I ever heard say holy moly like that," he said. "You say jeepers creepers too?"

Her mother was a preacher's wife, she blurted, the first thing that came to her head. Her father was, well, a preacher! She giggled nervously.

"Is he, now? How about that? A preacher's daughter. Get in the car." She paused. He shifted his foot. "Would you care for a spin with me?" he said.

"Okay."

His smile was musical as a lark. It penetrated. His palm lightly brushed her waist. When he tightened her seat belt, his hands lingered. A flood of warmth climbed to her cheeks and Salem yielded to a longing to fill the space between them with words.

She lived in a custom-built house of basic detail, on the generosity of the faithful. Pastor Ike could never spend on tiles for a new bathroom. No music no radio no TV: just Bible hour after dinner, she babbled. He never swore, either; the only time he did was when a visiting preacher from a nearby parish floated to him the idea of a Jazz Society for the youth of East Point to keep their hands from bedevilment. Even then (she glanced at her hands) Pastor Ike's swearing fell short of "f" or "s" words and he said "drummer" in place of "bugger." She spoke and spoke until he pulled the car to the side of a road and silenced her with his lips.

The kiss was as delicious as it was troubling. It filled her with a cavalcade of emotions, bands and bands of them. And she felt something new. Freedom. This man who made the sky resemble a crystal ceiling, who turned the ground at her feet to a fairy tale, he brought her freedom.

But that was no surprise, she later thought after their unchaperoned date. There was something magical about a man who walked through doors... who traveled between worlds. One minute he was there, the next he was gone. So on a whim, the first daring whim in her life, she presented a man to her father with intention and announced her plan.

"Father, you have met T-Mo," she said. "I am going to marry him."

They stood in the space between the back door of the main house and Salem's servant house. Pastor Ike eyed the male beside his daughter, took in the ripe plum color of his sleeveless t-shirt that carried bold white words on its breast, words that said: Hearts & Beds. Where was the mystery in those words? The intrigue? T-Mo had done bugger all, drummer drummer, to try and impress a possible father-in-law. Pastor Ike looked at Salem without indifference. Then he looked at the way the brazen boy or man stood, reckless, how he held his head, how a strange curiosity spread in his eyes. How the dazzle in his rainbow smile made his looks fetching despite dinosaur skin.

Might have been the hearts or beds, not the sleevelessness of his t-shirt, or was it T-Mo's unabashed smile? Whatever it was, it immediately squandered any goodwill Pastor Ike might have had. Gator skin or not, that alien buffoon standing with hair as yet uncombed beside his daughter... Pastor Ike had one question.

"This T-Mo," he said, speaking to his daughter. "Does he have a second name?"

Salem stood with tumultuous heart, looking at her father who directed words at her without removing his gaze from T-Mo.

"I am sure he does, Father..."

In the deadly silence that followed, Pastor Ike unmasked his hitherto somber countenance to disclose a vulnerability to fury. He purpled and a furious pulse pumped on his neck. It calmed, the pulse, and ceased being noticeable, as did the florid hue on Pastor Ike's face. Pageant fled into the house. She had looked and felt desperate at the boldness of her daughter; now perhaps she would hide her joyless face under the kitchen sink and clasp dismay in her trembling hands.

"And you are going to marry him?" There was no rebuke in Ike's voice.

"Yes, Father."

Ike's preacher face acquired calm, not sag, and with no more erosion of control than that which he had already displayed, with no dislike or hatred in it, he said, "You are both strangers to me. Get out of my house."