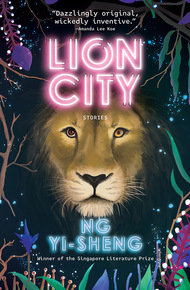

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright, journalist and activist. He is a two-time winner of the Singapore Literature Prize, which he received for his debut poetry collection, last boy, in 2008 and for his debut short story collection, Lion City in 2020.

His other publications include a compilation of his best spoken-word pieces, Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience (2016); the bestselling non-fiction book, SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century (2006); and a novelisation of the Singapore movie, Eating Air (2008). He also co-edited GASPP: A Gay Anthology of Singapore Poetry and Prose (2010) and Eastern Heathens: An Anthology of Subverted Asian Folklore (2013). He received his MA from the University of East Anglia's creative writing programme.

Singapore is known as a shiny metropolis, with all the conveniences of modern life. But the country takes on a new and darkly fabulous hue in Lion City, a collection of 16 stories that paint the nation in darkly fabulous hues.

This first collection of short fiction by award-winning poet and author Ng Yi-Sheng infuses myth, magical realism and contemporary sci-fi; and within these tales, a man learns that all the animals at the Singapore Zoo are robots; a secret terminal in Changi Airport has been set aside to cater to the gods; and Sang Nila Utama's minister actually tracks the strange animal that gives Singapore its name.

Exquisite, inventive, surprising and weird, Lion City's new perspectives on Singapore will leave you wanting more.

Yi-Sheng's collection blew me away when I read it, with each story more glittering and surprising than the last. I was delighted to be given permission to include it here, as I've been dying to share it with people! – Lavie Tidhar

"This collection takes apart the tropes trumpeted ad infinitum about Singapore … and reveals the magic of myth that underpins them all. The stories, with their subtle explorations of colonialism, capitalism and alienation, are delightful and discomfiting in equal measure."

– The Straits Times"Each story left the reader with a complex feeling that was not reducible or easy to forget."

– judges’ comments, Singapore Literature Prize"Combining the dark fairytale visions of Neil Gaiman and Intan Paramaditha with the deadpan wit of Etgar Keret, Lion City is a wildly imaginative collection of stories. Ng Yi-Sheng is a natural storyteller full of insight and humour."

– Sharlene Teo, author of PontiOn our third date, we went to the Zoo. "I'll show you where we make the animals," she purred, still tipsy from the Carlsberg. It was 3am, but she was the hottest thing I'd ever laid my eyes or hands on, so I said sure, why the hell not, let's go.

We zipped down Mandai Road on her chilli-red Yamaha motorbike, me behind her, gripping her waist, past walls and walls of choke-thick jungle: a mess of flame-of-the-forest and jelutong. I hadn't been to see the animals since primary school, so I'd forgotten about this bit of Singapore: a piece of wild left over from before the skyscrapers and bonsai gardens swallowed everything up.

We got to the alphabetised parking lot; slipped past the entryway, where all the tourist info desks and the orang-utan-themed café lay dark and silent. Then we came to an iron door painted with zebra stripes. She waved her card at an RFID scanner and pulled me in.

"This is where the magic happens," she whispered, sticking a tongue in my ear. And no joke, when I'm in her presence I think with my lower half every second on the clock, but the sight before me goggled my eyes so hard, sex was the last thing on my brain.

We were in a warehouse, filled top to bottom with shelves of animals. Tigers and tapirs and tamarins, cheek by jowl, squatting still next to each other like so many library books. Life-size beasts—and no toyshop reproductions, either: in the dark I could hear them breathing at me, yipping, whooping even, their jetty black eyes winking in the light of my Samsung screen.

She laughed at my slack-jawed stupor. "This never gets old," she said, and ducked into the shadows, leaving me alone with the thousand-odd animals. Seconds later, she popped up again with a fashlight in her left hand and a something in her right.

"Look," she said. Flanked by pillars of possums and penguins, the something wasn't impressive: just a pawful of wire mesh, cable spaghetti and the like, silicon garbage, the city's detritus. But then she tickled it under its chin—yes, it had a chin—and it stretched its arms and eyes and yawned and nestled again, buzzing against her breasts, kittenish, puppylike.

"Lion cub."

"Huh?"

"I've been working on it these past three months. New

design for infant lion. Release date's confirmed: edition of six, just in time for Chinese New Year."

She popped open her purse and pulled out these tiny fuzzy pyjama onesies, clenched the flashlight in her teeth, and forced that wriggling little baby robo-cub in. And what do you know, with the bot in those clothes, it really looked like a genuine little Simba, whiskers and all.

"Skin," she told me proudly. "Zoo's nest achievement. Pulls the wool over their eyes. We could make a toaster look like a tarantula."

"No shit."

But her attention had drifted. "Here, hold this," she said, and thrust the mewling cub into my hands. I fumbled and it bit me, but I stopped my curse halfway when I saw she was removing her shoes and her T-shirt, her jeans and her socks and her bra.

She clambered onto her workbench, her graceful arm clearing a space for us amidst the wires and screws, the flamingo feathers and fox fur.

"Come on up," she grinned. "Let's make some animals of our own."

I'd met her the way everyone meets these days: online. She'd liked my profile, she said. It was no fun going out with a bad boy: her hobby was preying on decent, hardworking office types who actually took a bit of work to corrupt.

Other things she liked included punk rock bands, graffiti art, the spiciest varieties of Indian food, the most slapstick of Hong Kong kung fu comedies. Anything that was loud and joyous and verging on the borders of good taste.

"I didn't have much of a childhood," she explained. I'd just bought her very expensive tickets to see one of those cruel-ty-free circuses at the Indoor Stadium, full of New Age clowns and acrobats instead of bears on unicycles. Now we were in Clarke Quay, amidst the art deco shophouses and colossal glass mushroom canopies, watching the intoxicated expats, watching the neon fountains, watching life itself. My clothes were sticky and my feet hurt, but I couldn't complain. I rather liked watching her like things.

And of course, there was the sex. It was crazy, savage stuff, the kind they're scared to mention in textbooks. Mondays at the photocopying machine, colleagues would stare at the network of lovebites on my throat, shocked, envious, unable to fathom that this colourless admin nobody might be the object of someone else's desire.

Usually we did it at the Zoo. After that first time, she'd decided her workbench was too stiff, too cluttered, and I wasn't wild about the dozens of mechanical eyes hovering over us anyway. Lucky for us, there were plenty of other love nests hidden away on the map. e baboon enclosure, the pony stables, the manatee tank.

After she came, which she did with flattering regularity, we'd share a cigarette. She'd extract a pack of Dunhill Reds from her purse and pass it between us, the sweat cooling on our bodies, stars above us peeking out between the trees and the necks of the spindly giraffes as they charged their battery packs.

She'd get all solemn sometimes. "I thought I was through with guilt," she'd say. "But yesterday, I was doing the elephant show and I saw this six-year-old Scandinavian kid. And he looked into my eyes, and I thought, he knows. He knows. He knows I know he knows."

We paused for a bit, listening to the lap of the reservoir water. Then I asked her if it'd always been this way.

"My god, yes. I mean, we're Singapore. We're a fully urban microstate in Southeast Asia. How else do you think we built the world's number-one zoo back in 1973?"

"Of course it was harder then," and here she blew a few smoke rings, "when folks were farmers and hunters and fishermen. They'd actually grown up around animals, some of them. And we had old tech. They must have smelled the trick a mile away."

"Why'd they keep their mouths shut?"

"Money, lover boy. Not bribery, mind you: they just knew we'd lose our pants if anyone squealed. And back then, everyone actually loved this country. We were all so hungry to succeed. So hungry that we were willing to tear everything down, all the villages and black-and-white colonial bungalows, and stack up these towers of glass and steel in their place."

There was a sound of crickets. Digital, maybe.

"But I'm not being nostalgic. This is nature. Renewal, like a snake shedding its skin. God, when was the last time I saw an actual snake?"

"What if the other zoos found out?"

"Are you kidding? Everyone's doing it. Basel, San Diego, Tokyo. Did you know, the giant panda's been extinct for a hundred years?"

Her fingers took aim and flicked the cigarette stub right into the designated trash bin.

"Gimme another," she nuzzled into my neck, and to my delight I found I was ready to go again.

It could've gone on forever like that, if it wasn't for that Valen-tine's Day stunt I pulled. I'd been shit-scared of her tiring of me, yawning during the same-old same-old fucking, gearing up mentally for another conquest.

So I decided to surprise her at work. Begged my boss for leave on the 14th, and spent it in the Zoo myself, wandering all over, a corny bouquet of a dozen red roses stuffed into my laptop bag.

I took my time with it. Stopped to sightsee. I saw the giant tortoise. I saw the polar bear. I saw the hippo and the gavial and the peacock and the dingo. Even hung out by the lion's den and checked out the listless, roaring felines—not that lifelike, I thought. I'd seen better.

But I didn't see her.

Texted her. No reply. Texted her again. Phone call, email, WhatsApp, Facebook, Line.

She's in a meeting, I told myself. She's asleep. She's gone on an overseas trip to repopulate the Okavango Delta with robo-cats, and never told me. I spent the hours dredging up every excuse my sorry brain could conjure, just to still the sour pool of vomit in my belly that'd hurl itself upwards if I even dared to consider the possibility that she didn't want me.

Around six o'clock closing time, she still hadn't replied, and suddenly a wave of acid reached the roof of my mouth, so I ducked behind some bushes and sprayed the heliconias with my overpriced lunch of yong tau foo. Getting up o my hands and knees, I saw a door. A familiar zebra-striped door. I jiggled at the knob. The scanner gave a low-pitched whine but the whole thing came open with a click, so I stepped in.

It was her workshop, all right: those endless shelves of critters, kingfishers and Komodo dragons and kangaroos, all stacked up in the darkness. And there in the centre of it all was a blue acetylene glow of a blowtorch, illuminating a woman.

It was her. But she looked different. e skin on her face and arms looked torn, as if by animal claws. And she was carefully welding the fingers of her right hand back onto her knuckles.

Maybe I let out a little cry, enough to startle her. She whipped her head around, showing the mess of circuitry in her cheeks, the fibreglass surface of her skull. Her eyes, the left one lidless, glowed iron-red in the flame. A low wail came from her throat, sub-sonic, making the very bones in my body tremble.

I think I shat myself. I can't be sure, because I was racing my way out of there, through the puddle of my vomit and the stinking mud of the flower beds, up and over and through the closing gates of the park, plunging into the nearest taxi, throwing my wallet at the driver to hightail us out of that place, before I could even begin to consciously process what I'd seen.

Hours later, while I was scrubbing myself raw in the shower at my parents' at, my phone buzzed.

She'd sent me a text message. "Tks 4 the flowers," it read, followed by the emoji of a rose. She turned up at the office a week later. It was ten in the morning, but I excused myself from the accounts committee and told everyone I needed just five seconds alone with her in the pantry.

It was odd, seeing her, scary and gorgeous as ever, on my home territory, against the dull sink and the corporate coffee mugs. I took a moment to brew us some Nescafé.

"You weren't supposed to see me like that," she said.

"No shit."

"I mean it, though. I'm one of the Zoo's newest designs.

Government secret. Very hush-hush."

It turned out she was a third-generation replicant: part of a master plan to build a cheap, highly-skilled labour force that'd integrate seamlessly into the populace. A unit of productivity and consumption, but minus the mess of childbirth and im-migration and voting rights. Basically, she was an economist's fantasy come true.

"You're very alive for a robot."

"Asshole. But yeah, I overcompensate. And it gets lonely in the warehouse."

She stared at her hands, then raised the mug to her lips. I did the same. Finally, she spoke.

"Is that it for us then?"

"It's complicated."

"Sorry I asked. Have a nice life."

"No. I mean..."

I checked the windows. Fuck, I couldn't believe I was doing

this. But it was either this or lose her, wasn't it? I shook my shoulders loose, reached into my chest, and gave a firm tug.

For the first time in years, maybe decades, my skin came off. I padded out on my four paws, huge and nervous and naked in my fur, tail waving back and forth. She seemed kind of confused, so I lay down next to her, placed my head in her lap and told her she could stroke my mane if she liked, I wouldn't bite.

"When the cities grew, us animals didn't just disappear," I explained. "We adapted. We've been living alongside men for centuries, tilling their fields, fortifying their fortresses, fighting their wars. And above all, surviving.

"We don't change back a lot. Too risky. Some of us even forget how—it's a tragedy, but at least we're around to mourn. And we're there in any city, no matter how cold or plastic. If you only know where to look."

Something like hours passed before she said anything. Maybe she was stuck in one of those programming feedback loops. I wouldn't know.

But eventually, she sat upright and grinned. "Lion cub," she said to me, tenderly, touching the fuzz on the tips of my ears. en she threaded her ngers into her hair, undid some hidden catch and peeled o the rubbery coat that enveloped her. All shining metal, she stepped over my squashed up clothing and gave my muzzle a kiss.

We unlocked the door. We stepped through, passing the cubicles full of my screaming colleagues, down the lift corridor, past the security guards and out the lobby, into the streets.

"Ready, lover boy?" she said, and swung a silver leg over my back. I gave a rumbling roar in assent.

"Perfect. Let's ride."