New York Times and USA Today bestselling author Rebecca Cantrell has published twenty-two novels that have been translated into several different languages. Her novels have won the ITW Thriller, the Macavity, and the Bruce Alexander awards. In addition, they have been nominated for the GoodReads Choice, the Barry, the RT Reviewers Choice, and the APPY awards. She lives in Hawaii with her husband, son, and a slightly deranged cat named Twinkle.

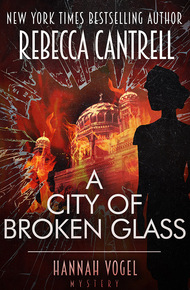

In 1938, after four years in hiding in Switzerland, journalist Hannah Vogel believes the coast is clear and takes the opportunity for a holiday with her 13-year-old son Anton. Traveling again under the name of Adelheid Zinsli, they arrive in Poland to cover the St. Martin festival, only to learn of the deportation of 12,000 Polish Jews from Germany. Hannah drops everything to get the story on the refugees, soon discovering that the wife of a friend of among them.

Running headlong into danger, she agrees to help find the woman's missing daughter—a promise which leads her straight into the arms of the SS, as well as those of Lars Lang, the lover she had presumed dead two years before. Injured, she and Anton are trapped in Berlin with Lars days before Kristallnacht—the Night of Broken Glass— where she is torn between ensuring their escape, and keeping her promise. But she can't turn her back on this one little girl, even if it plunges her and her family into danger.

I love Rebecca Cantrell's Hannah Vogel series, set in 1930s Germany. At that time, Germany was all about the secrets, and it was full of lies. The novels are dark, because that time was dark, but Becky writes with great humanity and warmth. If this is your introduction to Hannah Vogel, then you're in for a treat. – Kristine Kathryn Rusch

"In this fourth novel in a superbly written historical mystery series, Rebecca Cantrell once again tells a fast-paced story about the indomitable Hannah Vogel, a journalist, mother and fervent anti-Nazi Berliner…Set against the haunting backdrop of Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, the novel holds many surprises for Vogel, who becomes trapped in Berlin with Anton and a former lover. Cantrell drops you into 1930s Berlin, and the fear and chaos swirl around you."

– USA Today"Cantrell's fourth historical featuring journalist Hannah Vogel (after A Game of Lies) is compulsively readable. A palpable sense of dread builds, as we know that Kristallnacht, the Nazi pogrom of November 1938, is imminent. This award-winning series succeeds at weaving a very personal story into a well-researched historical survey. In an increasingly crowded genre period, Cantrell's series stands tall."

– Library Journal (starred)"With compelling characters and a narrative which makes it hard to put down, A City of Broken Glass combines romantic thriller with historical tragedy."

– Historical Novel Society"The opening of Cantrell's gripping fourth novel featuring journalist Hannah Vogel (after 2011's A Game of Lies) finds Vogel and her 13-yearold son, Anton, in 1938 Poland…Cantrell poignantly conveys the plight of Nazi Germany's Jews through the story of one child."

– Publishers WeeklyA herd of black and white Friesian cattle, a pair of mismatched draft horses, and a blacksmith's shop passed by the Fiat's windows. Nothing looked any different from any other Polish village. Yet today there were twelve thousand reasons why Zbaszyn was no longer a simple farming town. If only I could find them.

"Where do we go, Frau Zinsli?" Our driver, Fräulein Ivona, used the only name of mine she knew, my Swiss alias. My real name was Hannah Vogel, but in all of Poland, luckily, only my son Anton knew it.

"On." I pointed forward, although I had no idea where the refugees were housed.

Once I found them, I would talk to as many as possible, then the local doctor, the townspeople, and the mayor if I could. Getting quotes should not be a problem, as I warranted that many in Zbaszyn spoke German. Less than twenty years had passed since it was ceded from Germany to Poland in the Treaty of Versailles.

We approached a large brick stable with armed Polish soldiers clustered in front. They stood awkwardly, as if not certain why they were there, and kept stealing glances inside. Somehow, I did not think they guarded horses so closely.

I directed Fräulein Ivona to stop. She rolled the car to a halt next to a cluster of military vehicles. Clad in a tight white dress and jacket and high-heeled pumps, shoulder-length ash blond hair perfectly combed, and China red lips made up into a Cupid's bow, she stroked a languid hand over her hair, checking that every strand was in place before she turned off the engine.

"Anton," I said. "Wait in the car."

He gave me a look of utter disbelief before ordering his features. "All right."

I stopped, fingers on the door handle. He never gave in so readily. I studied him. He had no intention of staying put. The moment I was out of sight, he would follow. My thirteen-year-old daredevil would plunge straight into trouble and stoically bear the punishment later. As if reading my thoughts, he gave me a deceptively innocent smile. Freckles danced on the bridge of his nose.

I had to smile back.

I had brought him to Poland to enjoy time together while I researched a light feature piece about the Saint Martin's Day festival. Every November 11, Poznan held Europe's largest parade to celebrate the saint, known for his kindness to the poor. 1938's event promised to be grand.

The assignment should have been fun, but I viewed it as punishment. I had been banished to this backwater from Switzerland because my recent anti-Nazi articles had resulted in a series of threatening letters, and my editor at Zürich's Neue Zürcher Zeitung did not want to risk anything happening to me. If I had been a man, he would not have cared.

But I was not, so I had resigned myself to enduring my sentence quietly until I read the newspapers this morning and discovered that Germany had arrested more than twelve thousand Polish Jews and deported them across the border. I could not let that pass unnoticed, so I had headed to Zbaszyn to see the refugees myself. The paper had no one nearer. My editor would grumble, but he would also be grateful.

At least I hoped that he would.

Anton rubbed two fingers down the clean stick he had whittled. He pursed his lips as if about to whistle a jaunty tune to prove how innocent his intentions were.

"Fine." He was safer where I could see him. "Come with me. Stay close."

He clambered out eagerly. "Will there be riding?"

He loved to ride. In Switzerland, the stables were his second home. This would be like no stable he had ever seen. Suddenly cold, I turned up the collar on my wool coat. "I think not."

I pulled my Leica out of my satchel and snapped shots of the stable and soldiers. Their silver buttons and the silver braid on their dark uniform collars gleamed in the weak autumn sun.

I turned my attention to the stout brick building. Its tall doors measured more than twice the height of the men. Thick, too, with sturdy hinges and wrought iron bands fastened on the outside of the wood. They could safely contain horses. Or people.

Behind me, the Fiat's door slammed. I winced at the sound, and as one, all the Polish soldiers in front of the stable swiveled in our direction. So much for doing a quick walk around unnoticed. I wished that I had procured a car without a driver.

I hung my camera around my neck and hefted my satchel's leather strap higher on my shoulder. We walked to the stable and the soldiers guarding it. The soldiers admired Fräulein Ivona as she sashayed up.

Perhaps she would choose to use her assets to our advantage.

"Dzien dobry!" she said brightly.

The soldiers answered enthusiastically and tipped their queer uniform caps to her. The caps were round where they fit the head, but the top was square and the corners extended out an extra centimeter, like a combination soldier's cap and professor's mortarboard.

I looked through the half-open door behind them. The stable teemed with people. Most had a suitcase or small bundle, but I saw no food. A few souls peered out, looking as confused as the soldiers in front.

I itched to take notes.

The autumn breeze carried the smell of horse manure and the unpleasant odor of human waste. Presumably, no one had had time to set up toilet facilities for those packed inside.

Next to me, Fräulein Ivona wrinkled her nose. "We can't go in there. It's full of vermin."

"It is full of human beings," I reminded her.

"It's a stable." She shuddered. "It's also full of rats."

"There are worse things than rats," I said.

A young boy wearing a thick overcoat two sizes too big waved from inside the dark building. I put his age at around four. Anton waved back and took a step toward him.

When a soldier blocked Anton's way, he stumbled back in surprise. In Switzerland, stables did not have armed guards. Yesterday, in Poland, they had not, either.

Touching the shoulder of Anton's brown coat, now almost too small for him, I said, "Wait."

I handed the soldier on the right my press credential. He turned the document over with puzzlement. A small-town soldier, he had probably never seen anything like it. It sported an official-looking Swiss seal that I hoped might sway him into letting us pass.

"I am authorized to go inside," I told him.

Fräulein Ivona raised one perfectly shaped eyebrow skeptically. I had no such authorization, of course, as she well knew.

"I don't know," he said in German. He handed the credentials to the soldier next to him, and they discussed my case in Polish.

If I did not get in, the view into the stable might be all I had to write about. I snapped pictures of people on the other side of the open door. Because of the lighting, the quality would be poor, but it would be better than nothing. The soldiers shifted uneasily, but did not stop me.

When I had finished, I turned impatiently, as if late for a most important appointment. "Well?" I used my most officious tone. "Will you give way or must I speak to your superior?"

I hated using that tone, but it was often effective on soldiers, a hint that perhaps I had authority somewhere.

The soldier handed me my papers. "A quick visit."

A look of surprised respect flashed in Fräulein Ivona's eyes.

Anton walked toward the stable with his shoulders back as if he expected a fight. I quickened my steps to catch up. Together we stepped across the threshold.

Fräulein Ivona lagged behind, exchanging flirtatious words with the soldiers before following.

The long rows of horse stalls had not been cleaned. I suspected from the smell that the animals had been turned out only minutes before they herded in the refugees. Horses and manure smelled fresh compared to the odor of unwashed bodies and human waste.

Fräulein Ivona wrinkled her nose again, Anton clamped his jaws together, and I breathed through my mouth. I paused, waiting for my eyes to adjust to the gloom.

So many people. When I tried to do a quick head count, I realized that too many people crowded into the small space for me to do more than guess. A few stood, but most sat dejectedly on the dirty wooden floor, mud-spattered long coats drawn close against the cold. The women wore torn stockings and proper hats; the men fashionable woolen coats and fedoras. These were city people. They had not expected to exchange their urban apartments for a Polish barn.

"The guards say we may stay inside the stable for a moment only." Fräulein Ivona shifted in her white pumps. Mud smudged the once immaculate heels. "Your press credentials worried them."

I photographed as fast as I could, hoping that the dim light would be enough. Pictures would show what had happened more convincingly than any words I could muster. No one took notice of me as I clicked away. The tall ceiling absorbed sounds, and the refugees spoke in hushed tones.

Anton kept close and quiet. I wished that I had insisted he stay in the car so that he would not see what had happened to these people. But he lived in this world, and he was not keen on any attempt to protect him from it.

Yet I never would have brought him here had I known it was this bad.

I stopped in front of a woman sitting on the dirt floor, back propped against the edge of a stall. She cradled a baby inside her long black coat. I knelt next to her in the dirty straw.

"My name is Adelheid Zinsli." I used my best fake Swiss accent. "Do you speak German?"

"Of course I do." She sounded nettled, her accent pure Berlin. "I was born in Kreuzberg. In spite of what my passport says, I've never even been to Poland." She looked around the filthy stable and hugged her baby close.