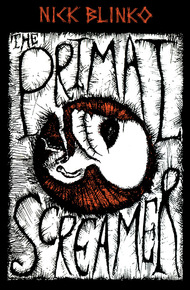

Nick Blinko was born in 1961. His band, Rudimentary Peni, whose records include Death Church, Cacophony, and Pope Adrian 37th, enjoy international acclaim in punk and avant-garde circles. A legendary figure in the "outsider art" scene, his paintings are exhibited across the world. He continues to write, paint, and make music in Black Langley, Hertfordshire, UK.

A Gothic Horror novel about severe mental distress and punk rock. The novel is written in the form of a diary kept by a psychiatrist, Dr. Rodney H. Dweller, concerning his patient, Nathaniel Snoxell, brought to him in 1979 because of several attempted suicides. Snoxell gets involved in the nascent UK anarcho-punk scene, recording EPs and playing gigs in squatted Anarchy Centers. In 1985, the good doctor himself "goes insane" and disappears.

This semi-autobiographical novel from Rudimentary Peni singer, guitarist, lyricist, and illustrator Nick Blinko, plunges into the worlds of madness, suicide, and anarchist punk. Lovecraft meets Crass in the squats and psychiatric institutions of early '80s England. This new edition collects Blinko"s long sought after artwork from the three previous incarnations.

A stunning short novel from the singer/guitarist for the seminal (and semenal!) punk outfit Rudimentary Peni. This is perhaps the only novel that is both transparently weird fiction and obviously autobiographical. Why yes, it does take place largely in a mental hospital, and in the form of psychiatric notes with some amazingly creepy doodles and illustrations. As an aging wannabe punk, I had to include this short sharp shock. – Nick Mamatas

"Dense, haunted, shot through with black humour."

– Raw Vision"Nick Blinko is a madman. That's not intended as pejorative opinion but rather a statement of plain fact."

– Maximum RocknRoll"The insights it offers into the punk scene and into the unsettling landscapes of its author's mind are fascinating. The whole book has a distinct sense of coming from a mind unlike most we are used to."

– The Big IssueTUES NOV 20

This day has been the most harrowing of my career to date. A young man was ushered into the surgery by his mother. As the drastic nature of his condition became apparent, I was sent for immediately.

Both his wrists had been cut, as deep as is possible without actually severing the arteries, which were semiexposed and quivering. He hadn't lost much blood. That which had been spilt was nevertheless a frightening purple colour. Fortunately, thick clots had already formed on the wounds. He had only slight feeling at the base of his thumbs, but otherwise his hands functioned perfectly. I was hurriedly informed that the case was an attempted suicide. He had really meant it.

I was greatly shocked. My stomach turned. The young man apologised for being a burden and for the obvious distress he was causing me; common enough sentiments among such cases. He also stated that this place was not where he had intended to be, as if he had failed to reach some preordained destination. I believe he said these things partly in reaction to the nurse who, in her fright, was muttering under her breath the cliche "it's a cry for help" and generally tut-tutting. Rather than offering the insight of amateur psychology, her response was more an effort to calm herself. I must have a word with her about this.

It is never pleasant dealing with emergency cases, but at least one can normally label such incidents as genuine accidents and quickly tend to the injury. However, I have never—even during my training—seen such grievous self-inflicted injuries as those that lay upon the wrists of Nathaniel Snoxell.

Within the hour, using a new "freezing" spray aerosol as a makeshift local anaesthetic, I had completed the stitching of his horrific lacerations. I found the work went better if I imagined myself stringing my violin. The nurse completed treatment with lints and bandages and an overall clean up of the affected areas, whilst I spoke with the young man's mother. I had seen the knife he had used and an antitetanus injection wasn't necessary—not that they're of any real use, save as placebos. The youth and I then retired upstairs to my room, the remainder of my afternoon schedule being cancelled. Two greatly appreciated cups of tea were brought up to us.

9

NICK BLINKO

I had never met Nathaniel before, his family doctor being one of my colleagues. The patient was tall and thin, slightly bent over, with short but wild black hair erupting over a high dome-like forehead. In fact, his head seemed too heavy for his neck to support and he held it to one side, virtually resting it on one shoulder. His eyes were very piercing yet somehow old. They were almost as black as his hair; an impression intensified by the glowing whiteness of his face. Dressed entirely in black he was on the darker, Gothic side of Romantic. He was not exactly clumsy in his movements, but he was self-conscious to a painful degree. He surveyed the view from my window whilst eagerly sipping his tea, which was piping hot. A somewhat fastidious appetite was, at least, intact, as he would take neither sugar nor milk. Eventually I coaxed him into a chair. I thought he looked like a mad doll, but quickly dispensed with the dangerous preconceptions suggested by his appearance, and began the gentle probing of his psyche.

"Well, what do I call you?" My usual opening gambit in such situations.

I already knew his strange and peculiarly pronounced name from the brief conversation I had had with his mother: "Nathaniel Snoxell".

"That's perfect iambic pentameter!" I had exclaimed. "Yes", she had said, suddenly calm. "He was a very poetic baby". I wondered, however, if he preferred to be called by an abbreviation

or nickname. I had expected at best a morose reply, but was surprised by his smile and his laughter. So many things, it seemed, had to be contained within that laughter.

"Nat".

This high-pitched, monotone, monosyllabic form of verbal communi- cation was, I soon found, greatly favoured by him and, at first, he practiced it almost exclusively. It had taken him a long time to reply, and after the utterance he returned to studying the pattern of my carpet.

"Well, Nat, where do we go from here?" I prodded. "Usually people are carted off to mental hospitals for what you've just done". I was attempting to provoke him into responding. "It's not exactly Britain's favourite way of ending it all, is it?"

Between long pauses he informed me of his high ideals and how the cruel world had shattered all his hopes; a familiar enough story. He grimaced frequently, lending pathos to each precisely worded statement. Nat had a magical reverence for certain things which had only recently been dashed. He had struggled to break free of his family, but the ties with his childhood had proved too strong, and he had allowed his mother to brow-beat him into finding work, in a toy shop. This was the antithesis of

10

THE PRIMAL SCREAMER

all his artistic and spiritual ideals. He had therefore decided to annihilate his existence.

So few and far between were his ejaculations that I had to be wary of putting words into his mouth and could not tell for sure if the picture I was building up of him was true, or merely a fabrication purposely designed to trap me.

Of the violence itself, he said the following. His parents had gone to work. His elder brother, who works the night-shift at a helicopter factory, was asleep. Funny, I'd had Nat down as an only child! His younger brother, with whom he shares a room, was at school. First Nat had tried jabbing at his arm with a variety of bizarre sharp objects. These included a jaw- bone of unknown origin, and some eighteenth-century scissors. (Perhaps a tetanus was in order after all.) Then he had taken a kitchen knife, which had recently been sharpened by his father, who was once a saw-doctor. Such personal minutiae seemed to obsess the gawky youth. This knife was the one the nurse and I had seen. Then Nat had set out for a nearby wood, "Oval Wood" I believe he called it. He had known it as a child. It was here that Nat had hacked away at his wrists but, he claimed, become too bored with the murderous task to finish the job. Lacking this passion, he had returned home, where his mother found him when she got back from her part-time work.

"It must have been very painful". I found myself adopting his pathos-filled grimaces. Although I quite often choose to mirror patients' expressions, this reaction was involuntary.

He spoke slowly but bravely of the most painful emotions, but refused to discuss sex. The abrupt ending of his spiritual quest had brought to the surface some previous conflict which he had been obliged to reenact.

We spoke, and gazed into space and at one another, for over two hours. His eye contact was good, if a little alarming at times. Eventually I concluded that he wasn't mad and informed him of my verdict. He looked a little disappointed, as if he felt he might belong in an "asylum", but it was difficult to tell. Whatever was happening to him was happening internally.

I told Nat I had some free time, late in the afternoons, and would be more than content to see him. I also informed him that I was well qualified psychologically speaking. We mutually agreed on an appointment for the following day. I gave him my card and he read it softly to himself: "Dr. Rodney H. Dweller M.A., M.B., B.Chir., D.Obst., R.C.O.G. . . ."

Afterwards I spoke again with his mother, and also his father, who by this time had been summoned from work. They seemed immensely

11

NICK BLINKO

grateful that I was taking the case on. Money was not mentioned. Instead I advised them not to allow Nat to let his hands flop, for he appeared to be all too ready to take on the guise of an elderly invalid.

The look in his eyes didn't belong to a youth of eighteen. I felt that the secret of what those eyes had gazed upon would not be surrendered lightly. It was this demoniacal-visionary aspect of Nat that has made my day so utterly disturbing, and not merely the physical carnage, upsetting though that was. However, I felt we had established a useful contact and, despite remaining darkly morbid and speaking openly of his desire for death, it was my belief that Nat would not suicide. My intuition detected within him a strand—a spark—of something strong. I felt that this would sustain him through the problematical days that inevitably lay ahead of us. I had made him promise to contact me if, at any time, he felt he would kill himself, and had sufficient confidence in him not to burden him with drugs, which would only compound his worries.