Brian Hodge is the award-winning author of eleven novels spanning horror, crime, and historical. He's also written close to 120 shorter works, and five full-length collections. His first collection, The Convulsion Factory, was ranked by critic Stanley Wiater among the 113 best books of modern horror.

He lives in Colorado, where he also dirties his hands with music, sound design, and photography; loves everything about organic gardening except the thieving squirrels; and trains in Krav Maga, grappling, and kickboxing, which are of no use at all against the squirrels.

To the warrior-shamans of the Venezuelan forest people, the drug is a sacred substance: part pain, part pleasure, all power. Skullflush is pure psychic whiplash … an exhilarating gateway to an advanced consciousness beyond time and species.

Deep in the Amazon, the primitive tribe has kept its secret safe from civilization. Until a rising drug lord ends up with a stolen six-kilo stash, and begins to peddle his prize in the nightclubs of Florida.

Tampa's thrill-seekers are eager to sample the pale green powder. But generations of urbanized decadence have left them jaded, shallow, and weak … too weak to handle the drug's mystic high. The ancient rain forest chemistry warps bone, muscle, and sinew in their city-soft bodies, setting free the ferocious power of man's basic nature.

On the rebound from a life in ruins, Justin Gray is the sole witness who can connect the fearsome power of skullflush with the carnage left in its wake. A marked man, with a new love and an unlikely ally from the heart of the rain forest, he's forced to learn the ways of the urban jungle, where everyone is both hunter and hunted.

Nightlife is a novel I read when it was first issued that has never left me. It draws on spirts of nature, the deep mysteries of the rain forest, and throws them in the face of "civilized" men who care for nothing but profit. It shifts through different worlds without moving much more than into the periphery of "the real." – David Niall Wilson

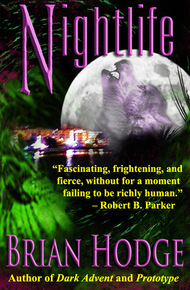

"Nightlife is fascinating, frightening, and fierce, without for a moment failing to be richly human."

–Robert B. Parker, author of the Spenser series"Color, sprawl, melodramatic action, and a feel not altogether unlike the prime of Miami Vice ... it's right in there like a Charles Willeford portrait of South Florida at its grotesque best. Lots of heat."

–Ed Bryant, in Locus"Switching back and forth between the mundane, the desperate, and the surreal, Nightlife displays a fascinating range: varieties of darkness."

–Farren Miller, in Locus"Hodge has come up with a scary winner. Unlike many of today's horror genre, Nightlife is believable … keeps you moving in a straightforward line until you get to the catastrophic end."

–The Santa Cruz SentinelThe jungle grew shadows, and the shadows grew eyes.

Across the Western Hemisphere, dawn was coming simultaneously to tens of thousands of locations. Millions of souls arising for their days, stumbling sleepily for radios and coffee and morning editions, oblivious to anything going on in the world not covered by Bryant Gumbel and the rest of the mass-media pack.

Equally oblivious to the denizens of high-tech civilization were those who rose with the dawn in the equatorial jungles of southern Venezuela. They were the Yanomamö. They were the Fierce People.

Angus Finnegan watched as the brown-skinned warriors crept near to the low stockade wall surrounding the village of Iyakei-teri. The raiding party, numbering just over twenty, moved like predatory cats, jaguars silently stalking prey. They carried bows made of palm wood, so hard it deflected nails, that were as long as the Yanomamö were tall. The arrows alone were six feet long, built for interchangeable tips. This morning war tips were in place — bamboo lanceolate coated with sticky brown curare.

Angus made a curious sight among the raiding party. Better than a full head taller than the tribe's tallest man, he stood a hulking six foot five. His long, unkempt hair and beard had gone white several years before, giving him a look of some Old Testament prophet sun-blasted toward madness in an unforgiving desert. He wore dirty khakis instead of robes, but the allusion wasn't far off. And at sixty years old, he looked to have the power of a man twenty years younger.

Kneeling beside a thicket of brush and ferns, Angus scanned through the gloom toward the village. Weak shafts of sunlight cut through at a slant, and the air was alive with the calls of birds. Macaws, parrots, others. Beneath the constant canopy of trees, the jungle was never very bright, and during the chill of dawn, visibility was murky at best.

But they had not come too late. The Colombians were still at the village; probably overnight. Their rowboat, powered by a large outboard motor, rested against the muddy bank of the stream near the village's main entrance. A few winding kilometers downstream, it linked with the larger Orinoco River. Odds were that the Orinoco would take them back to one of the more civilized areas with its own airstrip.

Before Angus even heard him coming, the headman of the raiding tribe, from Mabori-teri, was at his side. His name was Damowä, and like many of the raiders, he had painted his body black with the pigments they used in ceremonies and warfare.

"Are the enemy still here?" he asked in the native tongue. Angus nodded.

The black paint ended just under Damowä's eyes; above the line, those eyes spoke a profound mixture of ferocity and fear. "Will they have the wasp-guns?"

Angus lowered his great shaggy head for a moment, then raised it. Inside, what the Yanomamö called his buhii — his inner self — was cold. Their expression for sadness.

"Yes," he said softly. "I think they will."

Damowä nodded once. "Then we will just have to kill them before they point them at us."

If only it were as simple as it sounded. As Damowä silently padded away on his callused feet, Angus bowed his head once more. And left it there.

"Father Cod," he prayed, whispering, this time in English, "there will be deaths this morning. But I see no other way. And so I ask You, if there is to be punishment for them, that You'll heap it upon my head, and not theirs. Because I'm the one who led them into this. Through the blood of Your Son, amen."

Some of the Yanomamö had long since accepted the presence of God. Or Dios, as they sometimes called Him, depending on the nationality of the missionaries who had first arrived to convert them. In many cases, their religion was a mixture of reverence to Dios and a tenacious clinging to the spirit world served by countless generations of their ancestors. Of the ten thousand or so Yanomamö in the rain forests of Venezuela and Brazil, many had been converted to some degree.

Angus wondered, not for the first time, how often it happened the other way around. That a missionary was converted by the Yanomamö. He was willing to bet that he was the first and only.

Angus lifted the shotgun he'd brought. He wasn't one to leave all the dirty work to his primitive charges. If they were going to be risking death at the hands of an enemy village, at his bidding, he could do no less than join in the fray. And in their eyes, it made him just that much closer to being Yanomamö — and therefore human.

The cultural values running deepest in their souls were nearly a complete flip-flop of what Angus had known as a Scots-Irish Catholic from Boston. Christianity taught meekness, forgiveness, turning the other cheek. The Yanomamö believed that ferocity and avenging all trespasses was the key to living. Theirs was a society of small villages, usually numbering seventy to eighty, never more than 250. A village grows too packed, and it becomes one giant pressure cooker, with feuds and fights constantly erupting over sins real or imagined. Stealing food, sorcery, trysting with one man's wife while the husband's back was turned. Theirs was a society in which men beat their wives to show they cared, and a wife without scars was considered unloved. Should she cheat on her husband, he might go so far as to hack her ears off with a machete as just punishment. Yanomamö country was indeed a man's world.

It was a society in which nearly every afternoon, the men of the village would load yard-long hollow tubes with ebene, a pale green powder made from the inner bark of a particular tree. They would squat and take turns blasting the ebene into each other's nostrils with strong breaths. Ebene was hallucinatory, putting the takers into a trance in which they met with their personal demons. Experienced shamans could sometimes even coax the demons into living within their chests.

Naturally, men of God were appalled. And over the last few decades they had attempted to dispense with the naked pagans' filthy demons and bring them around to the ways of Western society. American Evangelicals, various Catholics, Spanish Salesians. Methodology and doctrine differed. The results were invariably the same: The gradual erosion of a culture that had heretofore remained pure for thousands of years.

Angus Finnegan had spent nineteen years with the Yanomamö of Mabori-teri. The first fifteen trying to strip them of their silly spirits. And the last four trying to repair the damage.

For in their well-intentioned meddling, the missionaries had managed to trip a row of dominos that would eventually lead to the twentieth century bulldozing right over one of the last sovereign Stone Age tribes in the world.

Missionaries led to mission posts. Posts led to airstrips. Airstrips led to increased contact with foreigners, including tourists with a yen for the exotic. Which led to exposure to diseases that the Indians had never encountered and, therefore, had no resistance or immunity to. A measles epidemic could kill, and had. Trinkets of the West had wormed their way into the Yanomamö way of life, even in the most remote villages.

At first such trade goods were innocuous — machetes, aluminum pots, steel axes and knives. Later came boats with outboards, and clothing. And shotguns.

Once the Yanomamö roamed their homeland nearly naked. All the men wore was a narrow waistcord, to which they tied the foreskins of their penises to keep them from dangling. That the sight of a naked body stimulated thoughts of lust had never entered their minds until the missionaries insisted so. Increasingly the Indians felt ill at ease without some sort of covering. Swimming trunks, loincloths, even Fruit of the Loom jockey shorts were often the rule rather than the exception now. Headman Damowä had come by a pair of which he was extremely proud, boasting drawings of a jubilant Mickey Mouse, whom he called "the happy rat."

But whereas clothing was harmless and sometimes even amusing, the arrival of shotguns was not. They were finding their way more and more into Yanomamö warfare. And where a quarter of adult male deaths were already due to warfare, an arms race was the last thing they needed.

A lot of the shotguns had even come from the missionaries themselves. Give them flashlights and shotguns, went the logic, and the Indians will be forever dependent on you for batteries and ammunition. Even the missionaries were not above petty squabbles over who would be first to reach uncontacted villages.

Angus was fully aware that violence and treachery were a part of daily Yanomamö life. Still, as bad as it could get, that seemed far preferable to hypocrisy. And hypocrisy was something the Yanomamö did not know.

It was learned by example.

Angus had long resided in hushuo — emotional turmoil. For he had come to know the Indians on a level that most of the missionaries never would. With dignity, nobility, wit, with a strength of kinship unsurpassed anywhere. As fellow human beings. While some of the missionaries outspokenly professed beliefs that the tribesmen were subhuman, on a par with animals.

Well then, let him who is without sin cast the first stone, Angus had thought at his breaking point four years ago. As for me, I'll have no part in destroying their lives any longer.

Not that they shouldn't come to know God. But God dwells in unspoiled jungles as readily as in suburban tract homes. There had to be a happy medium.

But the die had been cast, and its path was downhill all the way. Change could not be stopped. Impeded, perhaps. Which meant knowing what to expect. It was only a matter of time, then, before they were contacted by traffickers in the drug trade. At least in Iyakei-teri.

Angus still kept a calendar, kept track of days and dates. This was April, tail end of the dry season, and that had been of enormous benefit to hopes of ending things here and now. Intervillage gossip ran rampant during the dry season. During the rainy season, the trails between villages became impassable swamps, isolating each tribe for the duration. Had the Colombians come between next month and September, he would never have heard the news. About men from the outside world coming to trade fabulous supplies for a magical powder recently cultivated by the Iyakei tribe. A powder called hekura-teri, which had made them the most feared tribe around.

May God have mercy should it reach the outside world.

The raiders could see thickening plumes of smoke rising from within the village. Newly awake, the Iyakei were stoking their dwindling fires with fresh wood. It wouldn't be long now.

The raiders nervously worked wads of green tobacco in their mouths. They were edgy. Mabori-teri was a three days' walk away. Their traveling food — the bananalike plantains, a dietary staple — was nearly gone. And last night they could have no fire, since it might have gotten them spotted. As a result they were cold and feared spirits that might have approached overnight. Raids were always like this.

They could hear voices now, steadily increasing chatter.

Yanomamö villages consisted of an oval-shaped succession of huts called a shabono. Each hut was built adjacent to its neighbor, until the oval was enclosed. An open plaza in the middle. A log stockade surrounding the huts. Periodic gaps in both for entrance and exit. Overnight, these were filled with brush, a first-defense burglar alarm.

Angus watched and listened as the Iyakei removed the deadbrush and a few emerged. Voices mostly announced intentions to defecate. Bodily functions were as ripe for talk as plans for later in the day.

The raiders, concealed in brush and gloom, were as silent as ghosts, notching arrows into their bowstrings. Ready. Meat-hungry for war. They waited patiently as the Iyakei, armed even during this commonplace activity, relieved bowels and bladders. Alert for any sign of discovery. Angus tensed as a taller man in bush pants came out to do his duty as well, fifteen feet away. Long hair; certainly not Yanomamö. They kept theirs trimmed by razor-grass into bowl-shaped cuts, men and women alike.

Colombian. Toting along a small machine pistol. What Damowä had called a wasp-gun, because the spray of automatic fire reminded him of an attacking swarm of angry wasps. No doubt these were their fundamental trade gifts for the hekura-teri powder. Keep the tribe full of incentive for continued cooperation. All they'd have to bring next time would be ammunition. If the missionaries could play that game, why not the drug exporters?

Fifteen minutes later, the same Colombian led two others out, armed as well. Couldn't be any more left inside. Three men and their load would be pushing it as it was, given the size of the boat. They stood guard and oversaw Iyakei tribesmen, who came out toting canvas bags to load into the boat. Now or never. Angus signaled.

Damowä was the first to let his arrow fly, and a second later some twenty more went streaking in. A Colombian was the first hit. He took Damowä's arrow in the throat, the war tip snapping off as the shaft fell to the ground. As one voice, the Mabori roared their savagery.

In answer, the wasp-guns roared back.

Angus unleashed his own war cry and erupted from his crouch. He let the shotgun do the talking from then on.

His first blast peppered the leg of another Colombian and sent him sprawling into the mud of the stream bank. He jacked another shell into the chamber and spun, an avenging angel with broken wings, and blasted a tribesman clumsily attempting to sight in on him with a machine gun.

Pandemonium had arisen from within the village. Screams from the women and children, enraged cries from other warriors who came out to join the battle. Arrows whizzed back and forth, bullets chewed up trees and foliage all around the Mabori. Twenty feet to Angus's left, the machine-gun fire nearly tore one of the raiders in half. Six guns were firing at once, two with the Colombians and four in the inexperienced hands of the Iyakei.

Experienced or not, it didn't matter as long as they pointed in your direction and squeezed the trigger. You were just as dead or wounded. And the casualties began to mount up on the raiders' side quicker than on the Iyakei's.

Angus fell to the ground as bullets chopped at a tree above his head, then took out one of the gunners with another shotgun blast. One of the Mabori, Kerebawa, took out another one with an arrow. The wound itself, in the thigh, would never be fatal. But the curare wasted no time in taking over, paralyzing him from the outside in.

The Mabori were pinned down behind their cover, with little recourse left but to fire blindly into the air and hope the arrows got lucky. Dumb luck and instinct. While the injured Colombian laid down covering fire from the ground, his longhaired partner and a tribesman crouched low to finish loading the boat.

Another gunner fell, after which a Mabori warrior loosed an arrow and sprinted closer. With a quick burst of fire, his head showered apart.

Another Mabori screamed for vengeance and charged from his cover, a machete held aloft. He actually managed to outrun the path of bullets sent after him, and Angus watched as he descended upon the hapless gunner and hacked him across the face. A moment later, the avenging Mabori was skewered by the sharpened end of a seven-foot club.

The one saving grace for the Mabori was the Iyakei's unfamiliarity with their guns. They wasted ammunition, firing long bursts instead of short ones. And once their clips were empty, their attempts to reload were clumsy, those who had extra clips to begin with. It was the only thing preventing Mabori extinction.

Still, the Iyakei had managed to buy enough time to finish loading the boat. Angus swore aloud and clenched his teeth firmly when he heard the outboard fire up. He rose again, heedless of the danger, an arrow nearly skinning off his nose. He unleashed two rapid shotgun blasts toward the boat. When the injured Colombian rose to return fire, he took an arrow in the belly.

But the third throttled the engine and kicked up a sudden wake as the boat took flight. Angus could have wept with frustration. Unless a wild arrow claimed him, and this seemed less and less likely the farther away he got the entire massacre had been for nothing.

As he looked at fourteen bleeding bodies strewn across the forest floor, with more likely to fall, he could have ripped out his hair in great handfuls. Even greater than the sense of failure was the self-loathing over what he had done: He'd torn apart the very men whose souls he had come to save. If a man like that was not condemned to Hell, who was? His buhii was so cold by now, it was a glacier, scraping his heart raw.

He was about ready to motion to Damowä that they might as well retreat when he heard it. When they all heard it. The entire jungle split with the sound, and it held its breath to listen in awe.

From within the village came as unearthly a shriek as any of them had ever heard. Angus had heard something similar twice before, this dry season, and had prayed to never hear it again. Now it was worse, though. Now he was going to get a chance to witness its source close up.

It wasn't quite human. It wasn't quite animal. It wasn't quite spirit. It was somehow the worst of all three, and then some.

Every warrior still alive on the battlefield froze as it tore the morning air to shreds. The upper canopy exploded with birds that hadn't even been driven off by the sound of gunfire taking flight. From deeper in the jungle, monkeys screeched in fear.

Fierceness as a way of life be damned. Two of the Mabori flat-out turned tail and made tracks back through the jungle.

While it came running from the main entrance of the shabono.

Angus recognized it only by the clothing. Whatever it was now, it had been their chief. The Iyakei headman had ended up with a change of oversize clothes that he'd worn into filth-encrusted stiffness. Cotton pants, with the crotch cut out because the zipper was too bothersome to work. Ancient workshirt, unbuttoned and the sleeves rolled up. Apparently he had felt that clothes do make the man, and he'd learned enough Spanish to call himself capitán. Yes, it was the headman's clothing.

But the face … his face … his entire head.

"Iwä!" screamed one of the Mabori. "Iwä!"

Alligator.

From his upper chest on up, the headman's flesh had thickened into knobby hide, brownish green in color. From within chunky folds of skin, a pair of slitted yellow eyes gleamed. His mouth and nose were no more, at least not in human terms. The entire cranial structure had become rearranged into a long snout, flattened across top and bottom. And lined with so very many teeth. Sharp teeth. Snapping.

"Don't kill him!" Angus cried to the rest of the Mabori. Without need. They'd already learned their lesson once before. The hard way.

The headman came charging past his own awestruck warriors, locking onto Angus's voice. The yellow eyes alive with hunger.

Instinct said to shoot. Wisdom prevented it. And altruism thought, in the second before the iwä pounced, that perhaps his own death might buy more time for the rest to flee.

He lifted the shotgun in both hands, like a quarterstaff, as the headman bore him down to the ground. He wedged it sideways between the thing's jaws. Rows of teeth grated on metal, gouged out splinters of wood. He was bathed with the thing's foul breath, and as it sat atop him, it lunged relentlessly for his throat.

Claws. The man's hands had thickened into leathery reptilian feet, twisted claws instead of fingers. They flailed past the shotgun and ripped Angus's shoulder open to the bone. Blood soaked the ground beneath him.

The jaws, snapping, grinding through the shotgun…

The yellow eyes, inhuman, unblinking…

The face, mutated past anything he'd ever dared believe existed this side of Hell…

There was no point in struggling. To give in to its jaws would be the quickest way out. One brief moment of agony, then merciful oblivion.

But he couldn't. Life instinct was strong. Even as another swipe of the claws tattered his cheek. Even as yet another tore across his chest. Even as a claw worked its way between two ribs and punctured a lung.

He wheezed blood, swallowed it, coughed it.

A blur above him. No, they should run.

One of the burliest of the Mabori, a man named Ariwari, had come hurtling to Angus's aid, leaping onto the back of the headman and pulling him free. They rolled across the ground, and when they came to a halt, Ariwari was beneath him. One arm was clenched around the headman's swollen throat, the other around his stomach. The headman, the iwä, thrashed and bellowed another unearthly cry.

Kerebawa was close on Ariwari's heels, while the remaining warriors fired arrows to cover them. And as Angus watched, bleeding profusely and barely able to move, Kerebawa knelt beside the thrashing headman and tenderly rubbed his stomach. Ignoring the slashing jaws, the flailing talons. Rubbing the belly.

Incredible.

The thrashing weakened, and quickly ended altogether. Scrabbling limbs stilled and relaxed. Of all defenses — sleep.

Angus had seen this before, rolling an alligator onto its back and rubbing its belly. Something about the sensation and the backflow of blood into the brain induced sleep. That it should work here, now, was nothing short of a miracle.

Ariwari eased out from under the heavy body and scuttled away through the underbrush beneath a hail of arrows. Kerebawa reached beneath Angus's arms and locked his fingers to drag him away. Angus clenched his teeth against a feeble cry. The pain was almost beyond belief.

"I have you, Padre," Kerebawa murmured into his ear, and Angus watched his heels dig furrows on the jungle floor. "I have you."

Angus's head felt too heavy, a massive weight atop a fragile stalk. As Kerebawa pulled him backward, the remaining Mabori fell into position to retreat. Gradually falling back in teams to guard one another's escape.

And as Angus watched Iyakei-teri fade into the background, this savage green world turned gray. Then black. Then…

Nothing.

*

He came to later, and by the position of the sun, it looked to be midafternoon. Had they been home at Mabori-teri, the heat of midday would have driven most of them to their hammocks to rest.

As it was, they were resting now, ever alert for Iyakei warriors in pursuit. Or worse, the iwä.

Out of a raiding party of twenty-three men, they now numbered only fourteen. The bodies of the dead would remain, to be recovered later by the old women of Mabori-teri. Angus had always found it a strange double standard, that the young women were treated no better than chattel, but if they survived into old age, they were revered. Old women were often used as emissaries between warring tribes. Never harmed. Even when recovering the bodies of warriors who had slain the enemy.

Once home, the bodies would be burned. The remaining bones and ash ground into powder. The powder saved to be mixed with a soup of boiled plantains, and eaten.

Angus wondered if they would do the same with his bones. Burial by other missionaries? No. He didn't belong with them anymore. He belonged in Mabori-teri, in death as well as in life.

Kerebawa had tended the claw wounds as best he could, but they were gruesomely bad. If one of the shamans were here, he would chant a healing plea. Even so, it was not altogether unpleasant, feeling the numbness overtaking his body as he stared into the canopy overhead. Teeming with life that had no idea men killed one another over powders.

"I am cold inside for you, Padre," Kerebawa said. He held one hand behind Angus's head so he could drink some water.

Angus choked on a little, got the rest down. He patted the hand that fed him, felt the stinging trickle of tears. For the friendship to be severed. He'd known Kerebawa nearly all the young man's life. Angus didn't know precisely how old he was. There were only three numbers known to the Yanomamö: one, two, and anything greater than two. But he had been a small child when Angus had arrived nineteen years ago.

The way he saw it, Kerebawa had the brains and courage to assume headman status someday. If the tribe remained intact that long. Their survival depended on men like him, who could adapt.

Angus had singled out Kerebawa to introduce to the outside world. He'd told him of lands near and far: Mexico-teri. America-teri. England-teri. It was easier to put the names into a form and context Kerebawa would find meaningful. The -teri suffix denoted "village of." Mabori-teri meant, simply, village of the Mabori people. America-teri, then, village of the America people.

Nowhere was it more poignant, though, than when Kerebawa and the others had finally grasped the concept of Heaven: God-teri.

The Yanomamö had no way of conceiving of the enormity of the outside world. In their minds, they were the center of the universe. In their imaginations, the Venezuelan city of Caracas was merely a large shabono, just another succession of huts.

So Angus had shown Kerebawa the reality, in hopes that he might understand. And when the time was right, convey to the rest just how large and diverse the world was out there. Forewarned was forearmed.

Kerebawa had seen Caracas. Later, Mexico City. Eventually they had ventured all the way to Miami. The culture shock didn't seem to be particularly painful, no doubt in part due to the young man's schooling. As a child, he'd been educated with other Indian children in a mission school in Esmerelda, taught to read and write. He had learned to be marginally conversant in Spanish. Over the last four years, Angus had taught him a good deal of English as well.

A trilingual Yanomamö. Angus could have wept in bitter sorrow that such a rarity was needed. But better trilingual than extinct.

"Padre," said the headman Damowä, "today you became a true waiteri." A fierce one. "We will tell our children of this day. We will not forget."

Angus closed his eyes and smiled. The numbness had left his arms and legs nearly paralyzed. But he could smile. For now he knew that his bones would end up in their bellies. Living with them, in a strange way, forever.

Kerebawa gazed down at his teacher, his mentor, tears in his eyes. He wiped away the flecks of blood that Angus coughed up.

"The hekura-teri," Angus whispered. "They still got away with it. Do you know what that means?"

Kerebawa didn't twitch a muscle, didn't even bat an eye. But he knew. Angus could feel it. The young warrior understood it all.

"You wish to avenge my death … don't you?" There, appeal to centuries of inbred honor. Angus felt horribly manipulative. "Then you'll have to follow the path of the hekura-teri. And stop it."

"The world is too big," Kerebawa said. "It will eat me."

"Maybe not." A spasm shook his body; he didn't have long now. "The Colombians will take it back home, to Medellín-teri. To Vasquez. From there?" He shook his head in surrender.

Kerebawa simply closed his eyes in resignation.

"In my hut … papers, maps. The names of the men who took us to see the outer world. Barrows and Matteson? Use them all."

The paralysis crept up his chest to seize his throat. But no matter. He had said all he needed. After death, he knew his name would never be spoken again among their tribe. Their way of showing respect. But they would remember. Always.

And in the midst of this massive green cathedral, Angus let go his spirit, and let it soar.

While around his body rose the sudden sound of mourning.