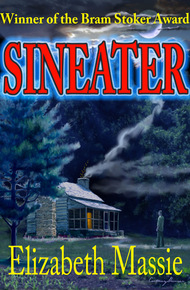

Elizabeth Massie is an award-winning author of horror novels and collections, short horror fiction, licensed media tie-ins, mainstream fiction, poetry, and educational fiction and nonfiction. Her novella "Stephen" and novel Sineater both received a Bram Stoker Award from the Horror Writers of America. Thy Will Be Done, her novelization of the third season of Showtime's original television series, The Tudors, won a Scribe Award from the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers. A film based on Elizabeth's short story, "Lock Her Room," was written, produced, and directed by Kai Soremekum and aired during the Showtime network's Annual Black Filmmaker Showcase Month. In 2012, Elizabeth's story, "Abed," was translated into a mid-length film by director/screenwriter Ryan Lieske, and it won the Radical Film Award at Thriller! Chiller!

Massie's more recent works include stories in the anthologies/magazines Tales from Crystal Lake, Dark Discoveries #25, Shadow Masters, and Qualia Nous, the zombie novel Desper Hollow (Apex Books), and the historical horror novel, Hell Gate (DarkFuse). Her new e-novella Fifty Shades of Hay (an erotic, over the-top country-fied satire of you-know-what, under the pen name JE Lames) will soon be released. She is also working on The House at Wyndham Strand, a new historical supernatural horror novel for young adults. Elizabeth like snow and geocaching and hates cheese and arrogance. She lives in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia with her husband, illustrator/artist Cortney Skinner.

The sineater is a mysterious, terrifying figure of the night, condemned to live alone in the mountains. He comes out only when a death occurs in the small community of Beacon Cove. As mourners at the wake turn to face the wall, the sineater enters to eat food off the chest of the dead, thus taking on the sins of the departed and cleansing the soul to enter heaven. The sineater has a family, yet even they must be asleep on the rare occasions he comes home for a midnight meal. The elder son, Curry, works as an oak weaver and prepares himself for life as the sineater when his father dies. Joel, the younger son, attends the community school but is either ignored or taunted by the other students.

A rash of violent crimes and murders rock Beacon Cove. The religious leadership announces that the sineater, overburdened with sins he has consumed, has become the embodiment of the devil. They must forbid him from attending wakes and do all they can to protect themselves from his evil. However, when troubled young Burke Campbell moves to Beacon Cove, he challenges the community's superstitions and fears and forces Joel to face the reality of who he is...and who his father is.

Sineater is the Bram Stoker Award-Winning novel of a young boy caught between dark forces, religious zealots, and a heritage that he can't shirk. Written against a stark background of deep country folklore and unflinching intolerance, this story will stick with you long after the last page has been turned. One of my favorite novels of all time. – David Niall Wilson

"Sineater is without a doubt one of the best horror novels I have read….The very detailed setting Massie portrayed made it very easy for me to feel like I was experiencing a part of the small town world detailed in the book. I can’t say enough about this highly recommended book!"

–Jenn's Bookshelves"I gotta tell you ... Sineater is one of the best, most touching, most intense "horror" novels I ever read. I actually cried at the end ... Real tears streaming down my face ... It is S-O-O-O-O good! Read it! Now!"

–Rick Hautala, author of Winter Wake, Chills, Reunion"The fanaticism that fuels the horror of this novel is very much alive in these parts. Sineater shows what a delicate balance exists between tradition and change, and how dangerous it can be when that balance is lost."

–Amazon Review"Sineater is exquisitely wrought terror that deserves every award and accolade it has garnered."

–Creature Feature Tomb of Horror1979

The young boy stands by his mother's bed, watching her scream.

Beside the boy is his younger sister, a tiny blond-haired five-year-old. The little girl's pale hair is plastered to her cheeks with tears and sweat. Her eyes are tightly closed. They wince with each scream. It is mid-June, and the room is hot and wet like a soaked wool blanket.

At the foot of the bed, sitting on a kerosene can, is the teenaged midwife. Her name is Jewel Benshoff. Jewel's eyes are nearly closed, too. The boy knows she does not want to be in this room; she does not want to be birthing the child who is soon to come. The boy's own fear terrifies him. But the midwife's fear excites him.

Curry Barker, the seven-year-old boy, the oldest of the two children, does not close his eyes. It is his duty to watch his mother. She said a new baby was the family's business, and it was not a private thing. Curry can see his mother's private things, though. They are splayed out between her spread legs, hairy and gaping and red. He makes himself look at them, and at the blood and wetness running out onto the mattress.

Curry's mother screams into the dishrag clamped in her teeth. She bucks her shoulders. Her fingers slash the air. Mottled, leaf-stained sunlight from the cabin window patterns her face. The rest of the room is dark, the walls of black wood and pitch. The mother's feet flex in the darkness, then draw up and push out violently. She takes a breath, a moment of silence, allowing faint goat bleats to be heard from outside. Then she screams again. The sound is loud and long, a throaty wail that rattles the bed frame.

Birthing is a family matter. Curry is there. His sister, Petrie, is there.

But, of course, the father is not there.

"Feel it coming!" cries the mother around the rag.

Curry clamps his teeth down. His eyes want to shut but he makes them stay open, and they sting. He watches the place between his mother's legs for it to come. The blood reminds him of the blood of the chickens he kills for the family meals; of the fresh, stinking blood of the deer his mother is teaching him to hunt. The white of the mattress makes him think of the white muscle of the stripped oak branches his mother is training him to form into simple baskets. Jewel's bloodied, grasping fingers make him think of the hands of the damned in the lake of fire of the Bible, reaching out for pity and salvation.

Curry's father's hands would be eternally damned if Curry were not alive. Curry's father, Avery, is the sineater. Curry knows he was born to keep Avery from God's holy and terrible burning lake when he dies.

Petrie squeaks, a muffled scream. Curry gives her a stem look, and then looks back at his mother.

"Push," says Jewel.

Curry's mother growls with the pain. "I feel ... ," she begins, and then cries out with the contraction.

Jewel frees the heels, and her trembling hands reach between the thick, vein-marbled legs. A slick black mass appears at the opening. The mother's feet rise slightly, the toes spread and clutching, then fall back to the mattress.

Petrie utters a loud gasp of fear. Curry takes her firmly by the arm. "You hush now," he whispers.

"Mama's dying!"

"I'll slap you you don't hush," says Curry. "She ain't gonna die. And if she do, Avery will send her to heaven."

Petrie wails louder then, and Curry drives his palm against her cheek. Petrie chokes, shudders, and falls silent, wiping the red spot on her face.

"You got to push now," the midwife says. The mother strains and grunts.

"Coming!" screams the mother on the bed. Jewel shudders visibly. Curry feels blood rush the veins of his hands, and cold rush the skin over his skull. If Mama died having this baby, Avery would have to come and send her to heaven. Curry and Petrie would have to put food on her chest. They would have to turn away to the wall while the sineater came in, ravenous with hunger, slobbering and seething with the heat of sin. He would eat up the food. Curry wonders if sineater's drool is poisonous.

Jewel's hands cup about the baby's head.

"Now!" the mother barks into the rag. She bends at the waist, her face rising toward the midwife like a phantom in the shadowed room. Wet baby shoulders jump out. A rank, rich smell of blood and fluids hits Curry in the face. He gasps.

The mother twists herself back and forth, as if trying to shake the baby free. "Now!" she screams again, and the dishrag is spit into the air. She grunts hoarsely and slams her fists into the bulge of her belly.

The baby shoots out, red, gummy face squashed and silent. The midwife quickly folds it within a white scrap of flannel, then snips and ties the cord. The baby squeaks once, weakly. Jewel puts it onto the bed between the mother's legs and leans over to press the mother's stomach to help the afterbirth along. She begins to hum a Jesus song. Curry has heard his mother sing this song. She sings it when she is afraid. She sings it late at night when there is no wake and she knows Avery will come home to eat supper alone in the kitchen after everyone has gone to bed.

"Mama?" says Petrie. Her hands are clasped together as if she were trying to pray.

"It's all done now, Petrie," says the mother. She seems to sink into the mattress, her voice faint and small. She sighs and slowly licks her lips. It seems as if she is trying to lick away the spots of sunlight. "So what we got then?" she asks the midwife.

Jewel says, "Boy."

There is a long silence. Curry tries to see the baby, but it is covered in the cloth. "A boy." The mother's words are soft now, the abating pain edged with wonder. "His name is Joel."

"Joel," says Petrie.

"Curry," says the mother. "Is Avery outside?"

Curry's mouth goes dry. He has to work his jaw in order to speak.

"I think he's near the mailbox, Mama." Curry's father is the sineater; he knows when to be where he needs to be. About an hour ago, Curry had gone out to the porch with Petrie to bring in an armload of towels from the bench. Down in the deep shadows, something had moved. Something huge, thick, and dark.

The sineater.

"Call to him, then. Tell him it's a boy."

Curry's heart tries to turn inside out. It scrapes against his ribs, and he digs his fingers against his chest through the thin cotton of his T-shirt. He doesn't want to call out to the sineater. He didn't know he was going to have to say something to the sineater. It is too dangerous.

"Curry, what's matter with you? I say, go now."

"Mama, I don't want to," Curry says. The family has little to do with the sineater. Curry, Petrie, and Lelia are to be asleep on nights when the sineater comes to eat his meal. The family is to be hiding in bedrooms, clinging to the blanket of night's oblivion when Avery Barker has no wake to attend, and takes his midnight supper in the cabin's small kitchen. Curry doesn't want to call out to the sineater.

Petrie rubs her fist under her running nose.

The mother coughs. "Give me the baby," she says to Jewel. "Give Joel to me." And to Curry, "You hear me, boy?"

Curry watches as his mother puts the baby under her chin and strokes its ugly wrinkled face. The baby has dark hair like his mother. It is still for a moment then it flails its legs suddenly, loosening itself from the white flannel. It startles itself and begins to cry.

Petrie reaches out and touches the thin baby arm.

Curry's teeth fight each other, making scraping noises in his ear.

Then he says, "Yes, Mama."

Jewel draws herself up on the kerosene can and tucks her face down as if the sineater is going to come into the room with her. Curry grits his teeth, then goes out of the bedroom and down the short hall to the kitchen. Petrie's baby kitten, found with its dead mother several weeks ago down by West Path when Curry went to look for may apples, lies in its wooden box near the stove.

Curry puts his hand on the door to pull it open. He does not want to call to the sineater. What if your voice carries your soul?

Mama would not ask him if it were dangerous. Mama knows what to do.

What if your soul comes out when you scream? What if it comes out and the sineater sucks it up?

Mama would not make him do something dangerous. He thinks for a second that Jewel Benshoff should have to call to Avery. Her soul didn't matter as much as Curry's, because he would have to be sineater when Avery died. Jewel is only a midwife.

Curry pulls the door open. He steps one step out onto the porch. He digs his fingers into his hurting chest, where his heart waits to see what he will do. He puts his other hand to his mouth. The fingers cup. He calls, "It's a boy!"

The words fly down the stone walkway toward the trees and the mailbox and what hides in the seething summer shadows. He feels a hot wind whip back up the walkway, like a stinking, devil's belch.

And before Curry can feel or hear more, he slams the door and throws himself against the safety of the sturdy wood, panting.