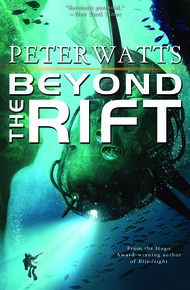

Peter Watts is a former marine biologist and a current science-fiction author. His debut novel in the Rifters series, (Starfish) was a New York Times Notable Book, and his novel (Blindsight) has become a required text in undergraduate courses ranging from philosophy to neuroscience, and was a finalist for numerous North American genre awards. His shorter work, including Beyond the Rift, has received the Shirley Jackson, Hugo, and Aurora awards. Watts's work is available in twenty languages and has been cited as inspirational to several popular video games. He lives in Toronto.

Skillfully combining complex science with finely executed prose, these edgy, award-winning tales explore the always-shifting border between the known and the alien.

The beauty and peril of technology and the passion and penalties of conviction merge in stories that are by turns dark, satiric, bold, and introspective. A seemingly humanized monster from John Carpenter's The Thing reveals the true villains in an Antarctic showdown. An artificial intelligence shields a biologically-enhanced prodigy from her overwhelmed parents. A deep-sea diver discovers that her true nature lies not within the confines of her mission but in the depths of her psyche. A court psychologist analyzes a psychotic graduate student who has learned to reprogram reality itself. A father tries to hold his broken family together in the wake of an ongoing assault by sentient rainstorms.

Gorgeously saturnine and exceptionally powerful, these collected fictions are both intensely thought-provoking and impossible to forget.

Does Peter Watts really need an introduction? Author of Blindsight? Hard SF maestro of his generation? Etc etc? I didn't think so. Who better to tell us about the hard, hard future than Watts? Just don't expect a cushy ride! – Lavie Tidhar

"A new book from crazy genius Watts is always cause for celebration—and this collection of short stories brings together some of his greatest work, including his mind-altering retelling of The Thing called "The Things." Known for his pitch-black views on human nature, and a breathtaking ability to explore the weird side of evolution and animal behavior, Watts is one of those writers who gets into your brain and remains lodged there like an angry, sentient tumor."

– io9 (Fall 2013 Must-Read Pick)"Canadian author Peter Watts is a biologist by training and a visionary by inclination. His novels are hard-edged yet coolly psychedelic extrapolations of our gene-modded future. Possessing the stern moral acuity of James Tiptree, he also exhibits the intellectual zest of Arthur C. Clarke…. His killer opening sentences ("First Contact was supposed to solve everything"; "Wescott was glad when it finally stopped breathing") are rabbit holes to strange futures."

– Paul Di Fillipo, The Barnes & Noble Review"[A] sharp and incisive stylist with a rather tragic, if clear-eyed, view of human nature, and the capacity for some remarkable hard-SF inventions."

– Gary K. Wolfe, LocusFrom "The Island"

We are the cave men. We are the Ancients, the Progenitors, the blue-collar steel monkeys. We spin your webs and build your magic gateways, thread each needle's eye at sixty thousand kilometers a second. We never stop. We never even dare to slow down, lest the light of your coming turns us to plasma. All for you. All so you can step from star to star without dirtying your feet in these endless, empty wastes between.

Is it really too much to ask, that you might talk to us now and then?

I know about evolution and engineering. I know how much you've changed. I've seen these portals give birth to gods and demons and things we can't begin to comprehend, things I can't believe were ever human; alien hitchhikers, maybe, riding the rails we've left behind. Alien conquerors.

Exterminators, perhaps.

But I've also seen those gates stay dark and empty until they faded from view. We've inferred diebacks and dark ages, civilizations burned to the ground and others rising from their ashes—and sometimes, afterwards, the things that come out look a little like the ships we might have built, back in the day. They speak to each other—radio, laser, carrier neutrinos—and sometimes their voices sound something like ours. There was a time we dared to hope that they really were like us, that the circle had come round again and closed on beings we could talk to. I've lost count of the times we tried to break the ice.

I've lost count of the eons since we gave up.

All these iterations fading behind us. All these hybrids and posthumans and immortals, gods and catatonic cavemen trapped in magical chariots they can't begin to understand, and not one of them ever pointed a comm laser in our direction to say, Hey, how's it going, or Guess what? We cured Damascus Disease! or even Thanks, guys, keep up the good work.

We're not some fucking cargo cult. We're the backbone of your goddamn empire. You wouldn't even be out here if it weren't for us.

And—and you're our children. Whatever you've become, you were once like this, like me. I believed in you once. There was a time, long ago, when I believed in this mission with all my heart.

Why have you forsaken us?

And so another build begins.

This time I open my eyes to a familiar face I've never seen before: only a boy, early twenties perhaps, physiologically. His face is a little lopsided, the cheekbone flatter on the left than the right. His ears are too big. He looks almost natural.

I haven't spoken for millennia. My voice comes out a whisper: "Who are you?" Not what I'm supposed to ask, I know. Not the first question anyone on Eriophora asks, after coming back.

"I'm yours," he says, and just like that I'm a mother.

I want to let it sink in, but he doesn't give me the chance: "You weren't scheduled, but Chimp wants extra hands on deck. Next build's got a situation."

So the chimp is still in control. The chimp is always in control. The mission goes on.

"Situation?" I ask.

"Contact scenario, maybe."

I wonder when he was born. I wonder if he ever wondered about me, before now.

He doesn't tell me. He only says, "Sun up ahead. Half lightyear. Chimp thinks, maybe it's talking to us. Anyhow..." My—son shrugs. "No rush. Lotsa time."

I nod, but he hesitates. He's waiting for The Question but I already see a kind of answer in his face. Our reinforcements were supposed to be pristine, built from perfect genes buried deep within Eri's iron-basalt mantle, safe from the sleeting blueshift. And yet this boy has flaws. I see the damage in his face, I see those tiny flipped base-pairs resonating up from the microscopic and bending him just a little off-kilter. He looks like he grew up on a planet. He looks borne of parents who spent their whole lives hammered by raw sunlight.

How far out must we be by now, if even our own perfect building blocks have decayed so? How long has it taken us? How long have I been dead?

How long? It's the first thing everyone asks.

After all this time, I don't want to know.

He's alone at the tac tank when I arrive on the bridge, his eyes full of icons and trajectories. Perhaps I see a little of me in there, too.

"I didn't get your name," I say, although I've looked it up on the manifest. We've barely been introduced and already I'm lying to him.

"Dix." He keeps his eyes on the tank.

He's over ten thousand years old. Alive for maybe twenty of them. I wonder how much he knows, who he's met during those sparse decades: Does he know Ishmael, or Connie? Does he know if Sanchez got over his brush with immortality?

I wonder, but I don't ask. There are rules.

I look around. "We're it?"

Dix nods. "For now. Bring back more if we need them. But..." His voice trails off.

"Yes?"

"Nothing."

I join him at the tank. Diaphanous veils hang within like frozen, color-coded smoke. We're on the edge of a molecular dust cloud. Warm, semiorganic, lots of raw materials: formaldehyde, ethylene glycol, the usual prebiotics. A good spot for a quick build. A red dwarf glowers dimly at the center of the tank. The chimp has named it DHF428, for reasons I've long since forgotten to care about.

"So fill me in," I say.

His glance is impatient, even irritated. "You too?"

"What do you mean?"

"Like the others. On the other builds. Chimp can just squirt the specs but they want to talk all the time."

Shit, his link's still active. He's online.

I force a smile. "Just a—a cultural tradition, I guess. We talk about a lot of things, it helps us—reconnect. After being down for so long."

"But it's slow," Dix complains.

He doesn't know. Why doesn't he know?

"We've got half a lightyear," I point out. "There's some rush?"

The corner of his mouth twitches. "Vons went out on schedule." On cue a cluster of violet pinpricks sparkle in the tank, five trillion klicks ahead of us. "Still sucking dust mostly, but got lucky with a couple of big asteroids and the refineries came online early. First components already extruded. Then Chimp sees these fluctuations in solar output—mainly infra, but extends into visible." The tank blinks at us: the dwarf goes into time-lapse.

Sure enough, it's flickering.

"Nonrandom, I take it."

Dix inclines his head a little to the side, not quite nodding.

"Plot the time-series." I've never been able to break the habit of raising my voice, just a bit, when addressing the chimp. Obediently (obediently. Now there's a laugh-and-a-half) the AI wipes the spacescape and replaces it with

..... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"Repeating sequence," Dix tells me. "Blips don't change, but spacing's a log-linear increase cycling every 92.5 corsecs. Each cycle starts at 13.2 clicks/corsec, degrades over time."

"No chance this could be natural? A little black hole wobbling around in the center of the star, maybe?"

Dix shakes his head, or something like that: a diagonal dip of the chin that somehow conveys the negative. "But way too simple to contain much info. Not like an actual conversation. More—well, a shout."

He's partly right. There may not be much information, but there's enough. We're here. We're smart. We're powerful enough to hook a whole damn star up to a dimmer switch.

Maybe not such a good spot for a build after all.

I purse my lips. "The sun's hailing us. That's what you're saying."

"Maybe. Hailing someone. But too simple for a Rosetta signal. It's not an archive, can't self-extract. Not a Bonferroni or Fibonacci seq, not pi. Not even a multiplication table. Nothing to base a pidgin on."

Still. An intelligent signal.

"Need more info," Dix says, proving himself master of the blindingly obvious.

I nod. "The vons."

"Uh, what about them?"

"We set up an array. Use a bunch of bad eyes to fake a good one. It'd be faster than high-geeing an observatory from this end or retooling one of the on-site factories."

His eyes go wide. For a moment he almost looks frightened for some reason. But the moment passes and he does that weird head-shake thing again. "Bleed too many resources away from the build, wouldn't it?"

"It would," the chimp agrees.

I suppress a snort. "If you're so worried about meeting our construction benchmarks, Chimp, factor in the potential risk posed by an intelligence powerful enough to control the energy output of an entire sun."

"I can't," it admits. "I don't have enough information."

"You don't have any information. About something that could probably stop this mission dead in its tracks if it wanted to. So maybe we should get some."

"Okay. Vons reassigned."

Confirmation glows from a convenient bulkhead, a complex sequence of dance instructions fired into the void. Six months from now a hundred self-replicating robots will waltz into a makeshift surveillance grid; four months after that, we might have something more than vacuum to debate in.

Dix eyes me as though I've just cast some kind of magic spell.

"It may run the ship," I tell him, "but it's pretty fucking stupid. Sometimes you've just got to spell things out."

He looks vaguely affronted, but there's no mistaking the surprise beneath. He didn't know that. He didn't know.

Who the hell's been raising him all this time? Whose problem is this?

Not mine.

"Call me in ten months," I say. "I'm going back to bed."