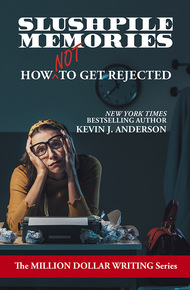

Kevin J. Anderson has published more than 190 books, 58 of which have been national or international bestsellers. He has 24 million copies in print in 34 languages.

He has written numerous novels in the Star Wars, X-Files, and Dune universes, as well as the unique Clockwork Angels steampunk trilogy with legendary Rush drummer Neil Peart. His original works include the Saga of Seven Suns series, the Wake the Dragon and Terra Incognita fantasy trilogies, and humorous Dan Shamble, Zombie P.I. series and The Dragon Business series.

He has edited numerous anthologies, written comics and games, and the lyrics to three rock CDs. Anderson is the director of the graduate program in Publishing at Western Colorado University, and he and his wife Rebecca Moesta are the publishers of WordFire Press.

He worked on the recent films Dune Part One and Part Two as well as the Dune: Prophecy TV series from MAX.

His most recent novels are Nether Station, Horn Dogs, Persephone, and Princess of Dune (with Brian Herbert).

An Amazon #1 bestseller!

Turn those rejections into acceptances—and contracts.

"Dear Author, Your story does not meet our needs at this time..."

You know your story is good, but still it was rejected. Over and over again. What are you doing wrong?

Are the odds against you?

How can an author climb to the top of a pile of competing manuscripts and actually catch an editor's attention?

"This book is a valuable resource for writers who want their SF&F stories professionally published."

– Amazon Reader"Anderson's decision to use real-world examples, many of which border on the ridiculous, makes this book a page-turner."

– Amazon ReaderIntroduction

I am no stranger to rejection—and I don't just mean my various attempts to get a date for prom in high school. I vividly remember the day I got my first rejection slip for a story I had submitted to a magazine.

I was twelve years old.

I'd always wanted to be a writer, and I spent every second of free time in my bedroom at an electric typewriter, pounding out drafts of a science fiction novel I'd been writing with since third grade. As a Christmas present one year, my parents got me a subscription to Writer's Digest magazine, and I learned all about manuscript format, markets, and the submission process. I bought a copy of Writer's Market, a big fat directory of magazine markets and their submission guidelines.

As a freshman in high school, I wrote a short story for history class about young twin boys trying to survive the Black Death in the 14th Century. I thought it was pretty good, and it got an "A" in history class, so I screwed up my courage, typed a clean copy, and mailed it to Boys' Life magazine, which seemed the appropriate market. I included a stamped, self-addressed return envelope, added a polite cover letter, and dropped it in the mailbox with a silent prayer. Then I waited … nearly three months.

I went to the mailbox every day, hoping and hoping, until finally the manila envelope came back. My heart fell. I tore open the envelope. Clipped to the front of the manuscript was a printed form rejection slip: "Dear Author, We regret that your story does not meet our needs at this time. Please try again." Cold and generic.

I was devastated. All that work, all that waiting—for nothing more than a rejection!

It was the first of many.

Undaunted, I resolved to try again and again—not just with the Black Death story, but with new stories. I would polish each one, make myself better, improve my writing. I vowed that I would get something published.

I combed through the Writer's Market, found magazines that might be appropriate for my stories. I developed an index-card recordkeeping system in a recipe box to keep track of where I had submitted my stories and which markets had rejected them.

I collected 80 rejection slips before I got my first acceptance—a one-page flash-fiction story that was published in a Wisconsin high school writings magazine. I received no pay, only a couple of contributor copies. I was a junior in high school.

A year later I finally sold a short story for pay—$12.50—to a small press magazine, Space and Time. I was thrilled! I could finally say I had been paid for my fiction.

Seeing the dollar amount, my parents were not overly impressed. It didn't come close to reimbursing even the postage I had invested so far. But it was a start.

I kept collecting rejection slips, hundreds and hundreds of them. Now, in retrospect, I can see that most of those early works weren't worthy of publication anyway. But my writing, plotting, characters, and descriptions improved. Practice makes perfect. I studied writing. I read voraciously. I tried to get better and better and better. Those form rejection slips were frequently replaced with personal letters, words of encouragement, suggestions for improvement.

I came close, so close … but not quite.

When I was a senior in high school, age 17, I received a particularly encouraging, detailed letter from Dr. Stanley Schmidt, the editor of Analog magazine—the holy grail for science fiction writers.

October 15, 1979

Dear Mr. Anderson:

Thank you for letting me see UPON THE WINDS. It had an intriguingly imaginative idea behind it, and I think the telling shows a good deal of potential. Your ability to visualize an exotic setting, and enable the reader to do so too, is quite good. However, your skills do need some honing (which is hardly surprising); a good deal of that should come with practice, but sometimes the process is speeded by pointing out where some of the needs are. In style, the first thing I notice is that you have a tendency to lean rather heavily on long, lecture-like explanations of background: in general, it's better to get right into the action and reveal background gradually and as unobtrusively as possible. It's hard with a story like this, where there's a good deal that has to be established right at the outset, but it can be done and needs to be done

The other thing is a matter of a special set of science-fictional skills, which are always helpful, but for Analog they're essential. You have to make sure your exotic setting works. I don't think this one does; the picture I get here is of the Noreed living in isolation on an otherwise essentially lifeless world. This won't work; an animal functions only as part of an interlocking ecosystem which, at there very least, must also include some plants (or things that serve the ecological functions of plants). What I'd recommend doing is backing all the way up to the formation of this planet and thinking out how it evolved and life evolved on it. The process will almost certainly lead to a richer ecology and fuller understanding of why the Noreed act as they do — which may turn out, inevitably, to be significantly different from the way you've pictured it here. But it will be a more believable way, because the reader will sense that what you tell him is part of a self-consistent larger whole, even if most of the supporting detail never finds its way into the final story. This is one of the most important "secrets" of writing successful science fiction about alien worlds. I don't know how much you know about the astronomical and biological thinking that's needed to do this sort of thing, but there's a basic body of it which is so important that you should familiarize yourself with it as soon as possible if you're seriously interested in writing science fiction; the time will be well invested, and I think you'll enjoy it. A few readings you should try, if you haven't already done so, are these: the two essays on creating imaginary worlds and beings by Poul Anderson and Hal Clement, in Reginald Bretnor's book SCIENCE FICTION: TODAY AND TOMORROW; I. S. Shklovskii and Carl Sagan's INTELLIGENT LIFE IN THE UNIVERSE; and Poul Anderson's IS THERE LIFE ON OTHER WORLDS?' and Stephen H. Dole's HABITABLE PLANETS FOR MAN. I think you'll find these not only help you learn to create solid settings, but are just bristling with good story ideas.

Meanwhile, keep writing, and I'll look forward to seeing your future work.

Sincerely,

Stanley Schmidt

Editor"

That rejection meant the world to me—this was the biggest editor in my field! It was one of the best things to happen to me as a young writer. I was energized and determined, and eventually (many years later) I did publish a story in Analog, and then several more. I became good friends with Stan.

I went to writing conferences, entered contests, and even won my first award as a writer … although it was a dubious honor, at best. At a large writing conference I received a trophy—engraved brass plaque and everything—naming me "The Writer with No Future," because I could produce more rejection slips by weight than any other writer at the entire conference. Though it was meant to be a joke, I took the trophy as a badge of honor, and it only increased my determination. I would not give up.

The happy ending is that I did rise to the top of the slushpile. I have now published over 150 short stories and 170 novels, many of which became international bestsellers. I have 23 million copies in print in more than 30 languages—so I don't let the rejections get me down.

My friend and mentor, Dean Koontz, once said that a writer's first million words are just practice … and if you can get paid for your practice, that's great. But you are not wasting your time. You are learning your trade.

#

This book will give you a look behind the scenes at how the slushpile for a magazine or anthology works. I'll give you tips on how to cope with rejection and, more importantly, how to avoid it in the first place.

I hope it'll help you get out of the reject pile and into print.