Matthew Hughes writes fantasy, space opera, and crime fiction. He has sold 24 novels to publishers large and small in the UK, US, and Canada, as well as nearly 100 works of short fiction to professional markets.

His latest novels are: A God in Chains (Dying Earth fantasy) from Edge Publishing and What the Wind Brings (magical realism/historical novel) from Pulp Literature Press.

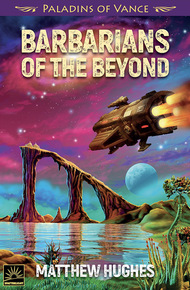

A NOVEL SET IN JACK VANCE'S DEMON PRINCES UNIVERSE

Twenty-some years ago, the five master criminals known as the Demon Princes raided the peaceful community of Mount Pleasant to enslave its five thousand inhabitants in the lawless Beyond. Now Morwen Sabine, a daughter of captives, has escaped her cruel master and returns to Mount Pleasant to recover the hidden treasure she hopes can buy her parents' freedom.

But Mount Pleasant has changed. Morwen must cope with mystic cultists, murderous drug-smugglers, undercover "weasels" of the Interplanetary Police Coordinating Company, and the henchmen of the vicious pirate lord who owns her parents and wants Morwen returned – so he can kill her slowly.

Barbarians of the Beyond is a return to "Jack Vance Space" and space-opera derring-do that follows in the science fiction Grandmaster's footsteps.

"I really enjoyed Barbarians of the Beyond. Matthew Hughes does Jack Vance better than anyone except Jack himself."

– George R.R. Martin"Lock the door, turn off the phone, get into a comfy chair, and deep-dive into a marvelous continuation of Jack Vance's Demon Princes series. Matthew Hughes is a treasure and Barbarians of the Beyond is a terrific adventure."

– David Gerrold"Matthew Hughes follows nimbly in Jack Vance's footprints, then breaks some fresh trail. First-class space opera."

– Robert J. Sawyer"Engaging and enchanting…a fine companion adventure to Jack Vance's The Demon Princes series, told with Matthew Hughes's excellent sense of charm, ethical complexity and exotic worldbuilding. Let's hope this is just the beginning!"

– Kurt BusiekThey touched down at the Nichae spaceport, sealed the yacht's hatches, and passed through the terminal to where the airship left every hour. It was mid-day on this part of Sasani when they boarded, mid-afternoon when the aircraft descended to its short tethering mast outside a huddle of flat-roofed structures of mudbrick and white stone that the ship's operator announced as Sul Arsam. A battered, long-bodied vehicle resting on four fat tires awaited them some distance away, its driver leaning against the dusty side with an expectant grin on his face.

Thanda activated his sonic repellent and Macrine did likewise. They stepped down from the airship's gondola and paused so Morwen and the two scrutineers could close in upon them, then they marched as a tight-packed quintet toward the disreputable old bus.

The other passengers, unwarned, found themselves under assault from a cloud of black insects that swept up from burrows in the ground and attacked any uncovered flesh, each biting off a minuscule but painful mouthful and flying away to deliver it to their grubs. The victims screamed and cursed and flailed their hands about their faces and necks, as they ran stumbling across the distance to the bus. Morwen and the Dispers marched stolidly on until they passed the grinning driver and boarded the vehicle.

The ride out to Interchange was only slightly less comfortable than the dash to escape the biters. The bus's suspension was a faint memory and they drove not on any semblance of a road but over the naked desert ground, which was rutted and pitted from the effects of seasonal floods brought on by infrequent, though torrential, rains. The driver's seat was cushioned, while the passengers sat on bare metal.

Their first sight of Interchange was the tumble of crumbling ocher sandstone rising above the desert's flat horizon, with a grove of feather-leafed trees at its crown. As they grew nearer, Morwen could make out the low-built concrete structures straggling along the base of the great reddish mound. They were gray and utilitarian-looking, and she imagined how they must have appeared to her parents as the slave carrier rumbled toward them.

The bus slowed and entered a walled space, then stopped on a paved apron. Grinning again, the driver opened the door. Another swarm of flesh-biters rose up as the passengers followed a series of yellow arrows across the tarmac to the nondescript door that bore a sign: Reception.

Inside, the new arrivals were confronted by a counter behind which a diminutive clerk whose skullcap bore the clasped-hands symbol of Interchange made entries in a ledger. He disdained to notice their presence. A sign instructed them: Take a seat and wait.

Most of the people from the bus shuffled across the tiled floor and sat. Thanda stared at the functionary for a long moment, then advanced to the barrier. The clerk ignored him. Thanda waited a little longer, then rapped his knuckles on the counter top.

The small man paused in his notations, then went back to work.

Thanda spoke quietly. "You are probably used to people who creep in here, intimidated by the circumstances under which they must pay the ransom that frees their loved ones from bondage."

The clerk did not look Thanda's way, but Morwen saw that he now had the little man's attention. She also saw him glance toward a button nearby on the counter top.

"I am not such a person," Thanda said. "But I am the sort of person who never forgets an insult, no matter how slight. Moreover, I am of the kind who can wait quite a long time to repay the affront, and during that period I can be most inventive in deciding exactly what punishment is merited."

The clerk now ignored the button. He put down his stylus and showed Thanda an attentive face. "How may I help you, Ser . . . ?"

"My name is of no moment. You may help me by providing information about this facility."

"At your service, Ser."

Thanda leaned on the counter. "Interchange holds funds until they can be disbursed as kidnap-ransom and the hostages released, yes?"

The clerk said that the correct terminology was "fees" for the "rescission" of "guests." How the guests came to be housed at the facility was beyond Interchange's purview.

"I do not care what the terminology is," Thanda said. "Is my assumption correct?"

"It is."

"Therefore, you are a kind of bank."

The functionary's first instinct appeared to be an inclination to argue, but a glance at Thanda's face vitiated whatever energy the impulse grew out of.

"Kind of, I suppose."

"Good," said Thanda. "We are making progress."

Thanda indicated his party ranged behind him. "We wish to open an account and deposit funds into it. We then wish to use some of those funds to purchase the liberty of some persons who were sold out of here more than twenty standard years ago."

The clerk looked apologetic. "That is not our normal business. Once guests' fees have been paid, they are discharged and no longer our concern."

"Regard my degree of patience," Thanda said, "as I expand your concept of where your 'concern' lies. You are accustomed to charging management fees for certain services, correct?"

"Correct."

"One such service could be to consult your records as to the 'rescission' of the fees for the two persons in question?"

"Yes."

"Which would identify the name and contact information of the party who paid those fees?"

The clerk visibly swallowed. "That information would be kept in confidence."

"Only appropriate," said Thanda. "But there would be nothing preventing Interchange from contacting that person and making an offer on behalf of a third party to bring the persons in question here for a substantial fee, would there?"

The little man thought about it. "Unconventional," he said after a while, "but conceivable. Of course, we would have to charge a commission."