British Science Fiction, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Award winning author Lavie Tidhar (A Man Lies Dreaming, The Escapement, Unholy Land, Circumference of the World) is an acclaimed author of literature, science fiction, fantasy, graphic novels, and middle grade fiction. Tidhar received the Campbell, Seiun, Geffen, and Neukom Literary awards for the novel Central Station, which has been translated into more than ten languages. He is a book columnist for the Washington Post, and is the editor of the Best of World Science Fiction anthology series. Tidhar has lived in Israel, Vanuatu, Laos, and South Africa. He currently resides with his family in London.

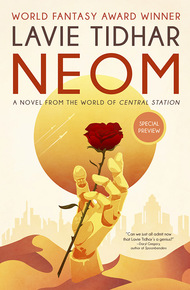

Special Preview: Excerpt from NEOM

Only Available in this StoryBundle

The city known as Neom is many things to many beings, human or otherwise. Neom is a tech wonderland for the rich and beautiful; an urban sprawl along the Red Sea; and a port of call between Earth and the stars.

In the desert, young orphan Elias has joined a caravan, hoping to earn his passage off-world from Central Station. But the desert is full of mechanical artefacts, some unexplained and some unexploded. Recently, a wry, unnamed robot has unearthed one of the region's biggest mysteries: the vestiges of a golden man.

In Neom, childhood affection is rekindling between loyal shurta-officer Nasir and hardworking flower-seller Mariam. But Nasu, a deadly terrorartist, has come to the city with missing memories and unfinished business.

Just one robot can change a city's destiny with a single rose—especially when that robot is in search of lost love.

My latest novel came out of a lockdown (I was supposed to be writing a different book!). It returns to the science fiction world of Central Station but is set mostly in the Arabian Peninsula and along the Red Sea, where a robot came one day to buy a flower. Who was this robot, and what was it doing? I wrote the book to try and find out. Neom will be out in November – here is an exclusive first look! – Lavie Tidhar

Beyond Central Station, that vast spaceport that links Earth with the teeming worlds of the solar system, there is a city. The city lies past the Gulf of Aqaba and the Straits of Tiran, in the old Saudi desert province that was once called Tabuk. The founders of the city called it Neom.

In sandstorm season the hot air is cooled down by gusts of wind blown into the wide boulevards of the city. The solar fields and wind farms that stretch from beyond the city proper deep into the inland desert capture all the energy Al Imtidad needs, feeding it back to serve all the city's needs.

On the shores of the Red Sea the sunbathers gather. The bars are open late. The kuffar sit smoking sheesha as children run laughing on the beach. Suntanned youths kite-surf in the wind. It is said it's always spring in Neo-Mostaqbal, in Neom. It is said the future always belongs to the young.

Mariam de la Cruz, who came trudging down Al Mansoura Avenue, was no longer so young, though she did not consider herself in the least bit old. It was more of that in-between time, when life finds a way to remind you of both what you'd lost and what lay still ahead.

Of course she was perfectly fine. But she was minutely aware of the ticking clock of senescence on the cellular level. Or in other words, ageing. Which was a problem in a city like Neom, which had been built and then sold—floated on the stock exchanges of Nairobi Prime and Gaza-Under-Sea and Old Beijing—on the premise that anything can be fixed, made good, made better, that things do not have to remain the way they'd been.

In Neom, everything was meant to be beautiful, ever since the young prince Mohammad of the Al Saud dynasty first dreamed up the idea of building a city of the future in the desert of the Arabian Peninsula and along the Red Sea. Now it was a mammoth metropolitan area.

Al Imtidad, the locals called it. The urban sprawl.

Mariam had grown up there, had never known another place. Her mother came to Neom from the Philippines in search of work, had met Mariam's father, a truck driver from Cairo who knew the desert roads from Luxor to Riyadh, from Alexandria to Mecca.

He was dead now, her father, had died in a collision on the border of Oman, delivering Chinese goods to the markets of Nizwa. She still missed him.

Her mother had lived on, remarried once, was now in a care facility on the edge of town, in the Nineveh Quarter. Much of what Mariam made went on paying the fees. It was a good place, her mother was well cared for. In the old days families would live together, would look after each other. But now there was only Mariam.

Now she walked, slowly in the heat, cars zooming past her in all directions. Latest model Bohrs, a Faraday roadster, a Gauss II black cab. No one ever named cars after poets, she thought. Her own taste in poetry ran to the neo-classical: Ng Yi-Sheng, Lior Tirosh. They weren't the most famous, they just . . . were.

The cars swarmed around her, ferrying people every which way. They resembled the movement of fish flocks, the way they flowed independently yet in unison. It was illegal to drive a car in Al Imtidad. They were all run by an inference engine. It was usually the way of things, Mariam had found. People didn't trust other people for things like driving them, or for making investment decisions, or for medical care.

Unless, of course, it was a matter of status.

Al Mansoura Avenue, on the outskirts of midtown, was a pleasant road with many equally-spaced palm trees providing shade along the pavements on either side. The buildings were only a few stories tall, shops on the ground floor and nice spacious apartments above. Dog-walkers walked other people's dogs and nannies pushed other people's babies along the pavements. Cafes were open, blasting out cool air, and the patrons who sat sipping cappuccinos were busy interacting with each other in a meaningful manner, signalling to any passer-by that they were not merely relaxing but engaging in important face-to-face connectivity.

The shuttle plane to Central Station flew low overhead. Mariam passed the cafes, the shops selling cultivated pearls and imported perfumes, anti-drone privacy kits, an artisanal bakery wafting out the smell of fresh sourdough loaves and sticky baklawah. A florist stall sold bouquets of fat red roses. The people who lived on Al Mansoura were the upwardly- mobile, and they lived on hope. Hope was a powerful drug.

Another shop, this one renting out luxury watches. She never understood that desire to wear these overpriced, tiny mechanical machines that measured time. Her own watch was a plastic knock-off from the roadside markets in Nineveh, mass-produced in Yiwu, shipped across the world on the Silk Road that China built. The sort of junk her father would have ferried in his truck. But people wore watches to tell the world they were rich, successful, that they were going places. That they took time seriously.

Mariam did too. She was paid by the hour. Now she made her way to the address and punched in the code and rode up in the elevator to the Smirnov-Li apartment. It was a nice spacious apartment, with floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the city and the sea far in the distance. The sort of place that was always rented because it was too expensive to own.

Hardly anyone owned their own place on Al Imtidad. Everything in Neom was rented—living spaces, luxury watches, people.

Smirnov and Li weren't in. Mariam filled a bucket with warm soapy water in their gleaming bathroom. They were a nice, handsome couple, men in their early thirties, their wedding photos hanging in the living room from some beach-side ceremony in Fiji or Bali, anyway one of those places people always went to get married in. While Neom's land belonged still to the Saudis, the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice—the Mutaween—had no power beyond the border, and Mutaween agents had no power of enforcement within the sprawl. Neom's freedom had been part and parcel of the pitch package long before it ever had stocks for sale, when it was still just a corporate promo on a video-sharing site, some wealthy prince's unlikely, faintly ridiculous dream.

As Mariam cleaned the windows she stared out at the city. She liked having the apartment to herself, imagined herself living there, in all that minimalist simplicity. Sometimes Smirnov or Li would be there, but mostly they left her alone to do her job. It was a Neom thing. She knew from the last time she'd seen them that they had been talking about having children, which caused an argument since Smirnov (she never learned their first names, which was another Neom thing) was pushing and Li was resisting, worrying about the costs of an exowomb and arguing over the baby's eye colour.

She cleaned and vacuumed, fed the fish, dusted the shelves, took out the trash and dumped it into the automatic recycling chute.

If people were any poorer they just used some general- purpose household robot. If they were much poorer, they cleaned by themselves. If they were much richer, they had live-in staff. Li and Smirnov were at just the right income level to employ a human cleaner on a part-time basis. Just enough to drop casually in conversation, "Oh, yes, we just had the cleaner in yesterday," and so on. "Lives down in Nineveh, the poor thing." They were nice people and they paid her well enough, and on time, which meant something. They always told her she could have whatever was in the fridge but, whenever she opened the gleaming chrome door, all she found inside were probiotic yoghurts. People in Neom took care of their gut bacteria the way people in other places looked after their children. Which is to say, personally.

When she left the apartment that afternoon she was hot and she was hungry, and she grabbed a falafel at a roadside stall. Oil ran down her chin and she wiped it with a paper napkin, not caring for the moment about the heat or anything else. Everybody loved falafel. A street was not a street if it didn't have at least one vendor on it.

She passed a branch of the old Banque Nationale de Djibouti, looking for her friend, Hameed. He could usually be found on the corner there.

Then she saw him, sitting as usual with his back to the wall of the bank. Looking up at the sun.

But something was wrong. Something about his posture, his stillness. She took a step forward and another. Then the wrongness intensified and she began to run.

When she reached him, for just a moment, she couldn't take it in. His face, usually so animated, was slack, the smooth skin scorched and torn, the head itself pummelled senselessly until it hung crooked from his neck. His left eye had been gouged from its socket and hung loose over his face. One of his arms was broken and his knees had been smashed, the whole motionless body crudely destroyed and left for dead.

"My God," Mariam said. "My God."

Her fingers stroked his cheek, tracing the soft flesh rubber. The biometric skin had been torn in chunks from the face, revealing the crude mechanical skull and brain behind it. It too had been bashed and broken, and the automaton sat lifeless against the wall.

"Hameed?" Mariam said. "Hameed?"

But there was no response. The one remaining eye stared into nothing. Mariam was shaken, for this was a kind of violence she had seldom experienced, and Hameed was her friend.

He had been a general purpose caregiver-automaton, the sort they used to have installed in old people's homes. He was old, had been made obsolete years before. Usually they'd dump the mannequins afterwards into recycling but Hameed escaped that fate and lived out on the street. He was always very chatty and he smiled a lot and people seemed to like him.

She wiped her eyes. Stood up, looked at the damage. It must have been kids, teenagers who did this. With crowbars or anything crude, some sort of bat. Mariam shook with anger. She called the shurta.

Other passers-by went round, ignoring the sight of the broken automaton. On a balcony on the other side of the road two women were having tea. A fruit-juice seller went past with his cart. A group of Djibouti bankers went past in faded suits.

Djibouti, situated on the Horn of Africa and the Gate of Tears, was the central hub of underwater cables linking Asia, Africa and Europe. They had gradually gained in political and economic importance as the digital overlaid the physical.

But they paid no attention to Hameed, either.

It wasn't long before a shurta cruiser pulled up, and an officer stepped out. The car was a sporty Marconi, striped green and white, with a curved sword on the side, and the officer was slightly less sporty, but with neatly trimmed black hair and polished shoes and an easy smile.

"Hey, Mariam," he said.

"Nasir," she said, relieved. She had known him since kindergarten, his mother had been friends with Mariam's. "I didn't know you worked midtown."

"I'm a sergeant now," he said, smiling a little self-consciously. "What seems to be the problem, Mariam?"

"It's Hameed," she said. "He's been murdered."

Nasir dropped the smile and approached the prone body of the automaton. He knelt down to look at the damage.

"I'm sorry," he said.

"You knew him?"

"Everyone knew Hameed. He was practically a fixture of the neighbourhood."

"So? Can you do something? Can you catch whoever did this?"

Nasir straightened. Looked at her closely.

"Would you like some tea?" he said. "There is a place around the corner from here."

"Can you catch them!" she said.

"Mariam, it's not a person," Nasir said. "It's just a chatbot with a face. It was designed to be appealing to people, but there was no consciousness, nothing but a set of pre-scripted responses in a neural network. It's not like one of the real robots, the old humanoid ones they made for the old wars."

"But you can't—!" she said. "You can't just not—"

"I could get them for property damage," he said, "only Hameed wasn't anyone's property, he was, well, discarded. I suppose someone would have to clean it up, so maybe you could get them on littering. Yes—" He brightened. "Littering is a serious crime. We're always on the lookout for—"

But she was no longer listening to him. She nodded, politely, when he spoke, and when he offered her tea again she shook her head, No, thank you, and Yes, I'm quite all right, and then he called it in to the street maintenance crew to come and clean up, and then he was gone again.

But before he'd left he said, "Look, it was really nice running into you again." He shifted from foot to foot.

"Would you like to, I don't know, go out for dinner one night? Catch up on old times, you know . . ." he trailed off.

"Sure," she said. "Sure. I'd like that."

"All right, then." And he smiled that beaming smile again. "Then I guess I'll see you."

"I'll see you, Nasir."

Then he was gone, and she was left alone with the robot.