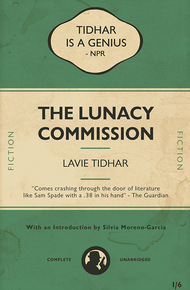

British Science Fiction, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Award winning author Lavie Tidhar (A Man Lies Dreaming, The Escapement, Unholy Land, Circumference of the World) is an acclaimed author of literature, science fiction, fantasy, graphic novels, and middle grade fiction. Tidhar received the Campbell, Seiun, Geffen, and Neukom Literary awards for the novel Central Station, which has been translated into more than ten languages. He is a book columnist for the Washington Post, and is the editor of the Best of World Science Fiction anthology series. Tidhar has lived in Israel, Vanuatu, Laos, and South Africa. He currently resides with his family in London.

With an introduction by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, author of New York Times Bestseller Mexican Gothic

Lavie Tidhar's ground-breaking, award winning novel A Man Lies Dreaming introduced Adolf Hitler as a down-at-heels private detective, forced to eke out a miserable living in 1930s London. Forgotten by history, the man now calling himself Wolf is the lowest of the low, suffering fresh humiliations at every turn.

Now Wolf is back, in five darkly comic new stories that see him take on blackmail, murder, and theft – not to mention his old comrades.

A brilliant alternate history noir with a heart, these stories are in turn shocking, horrifying and comic, as could only come from the mind of World Fantasy Award winner Lavie Tidhar.

After I wrote A Man Lies Dreaming I still couldn't get the voice of Wolf (my alternate history version of Adolf Hitler) out of my head. To try and get rid of him I wrote a story, "Red Christmas", one year, but he kept hanging around and I wrote four more stories – with tales of blackmail, theft and murder – before finally and mercifully he left. I hope he never comes back, but these were fun enough to finally put together into one volume. – Lavie Tidhar

"Tidhar is a genius at conjuring realities that are just two steps to the left of our own."

– NPR"A warped genius... There is no one like him."

– Ian McDonaldONE

Red Christmas

In another time and place, Shomer still has Fanya and the children. He watches his wife as she lights the Hannukah candles on the windowsill. A hush has settled over the ghetto, and the children, Avrom and Bina, watch the weak, flickering lights of the candle stubs. Shomer watches them too, how they struggle to survive, to hold this flickering flame. He knows that soon, no matter what he'd do, these lights will burn out and die.

But for now, he has them all, and there is no happier man alive than Shomer, that one time purveyor of lurid tales, back when there were still rags to print such nonsense; and after the lighting and the blessing, he takes the children out for a walk. How thin they are, he marvels, watching them spin their makeshift dreidels with the other children, squatting on their haunches in the corner like born gamblers. 'And are we not all gamblers?' he says to Yenkl, who materialises out of the Yiddish Theatre's door, still dressed as Kuni Leml. 'Betting against the odds?'

And Yenkl merely nods his head, and rolls a cigarette with long thin fingers. 'They say the trains will soon take all of us all to the east,' he says. 'A promised land of miracles and plenty, eh, Shomer?'

And Shomer knows the children listen, and he knows that he cannot tell them. Rumours only, whispered, of what's happening in the east, what they do to the Jews in those camps in Poland. Rumours only, and surely there can be nothing in them, there can be no truth—

And so his mind shies from the glare of time present and travels elsewhere, to another time and place of his own making, and to a sordid little tale of shund, that is to say, of pulp—of blackmail, violence, and murder.

1.

She puffed on the cigarette with quick, nervous jerks of her hand. The fur coat she wore was mottled in places and her big, dark eyes looked at me with a sort of nervous excitement. 'I am being blackmailed, you see, Herr Hitler.'

I hated the smell of tobacco. I hated the cold of my office, above the Jew baker's shop. I hated London, and this cold, soulless island on which I'd found myself, a refugee. I hated what I had become.

'It's Wolf, now,' I told her. 'The name. Just Wolf.'

She shrugged. She didn't care who or what I was.

You probably wouldn't remember her, now. I will call her Elske Sturm, though that was not her real name, exactly. She often played the kind of girl who drowned at the end of the movie. Sometimes I wished a rain would come and drown the whole world, and everything in it. Once, I was going to conquer the world. Now I was a piece of gum stuck to a spassmacher's shoe.

I said, 'Blackmail, Fraulein Sturm?'

'I have been sent pictures,' she said. 'Compromising photographs. The blackmailer threatens to, well, you can connect the dots.'

'Is there any more?' I said. There usually was.

She shrugged. It was a very Teutonic shrug. 'The… other person in the photographs,' she said. 'He's married.'

'I see.'

'We're in love.' She said it like it meant nothing, and she was right, because it never does. It was just an ugly case of adultery, the kind I wouldn't usually touch, but I needed the money. It was December, 1937, and it was a cold winter and only going to get worse. I was behind on my rent and down on my luck, and the old wound from the concentration camp the communists had put me in after my Fall ached in cold weather.

'Who is the other party?'

'I'd rather not mention his name,' she said quickly. 'He is a prominent politician.'

'…I see.' And I did. She was just an actress, and no one expects high morals from a simple bird of paradise. They were pretty and empty headed, and dirty pictures would just as likely help their careers as ruin them. '…Does he know?'

She shrugged. 'I don't know,' she said in a flat voice. 'We haven't spoken about it.'

She was lying, of course. She was never that good an actress. I took down the details. She had met with this man three times in different hotels around London. The blackmailer must have followed them, snapped photographs through the window of one of the rooms. I could imagine it easy enough. I said, 'Do you have the note?'

'Yes. Here.' She pushed it across my desk. The message was short: Bring £300 in notes, Leave the bag by the Eleanor Cross, Sunday, 1pm, come alone, I will be watching you. No funny stuff.

'I had to look up the Eleanor Cross,' she said. 'It's that hideous monument outside Charing Cross Station.'

I nodded. I knew the place. I myself had arrived in London into that cesspit of racial impurity that was Charing Cross. It had become the gateway into London for us refugees from the Fall. The Jews and the communists held Germany now in their filthy hands, and good, honest Volk, proud Aryans, were now the scum of Europe, beggars arriving on the filthy shores of England cap in hand. How I hated them! How I hated them all!

'You will make the drop? Alone?'

She bit her nails. 'If that's what you'd advise.'

'It is.'

'And you will…?'

'I will be there. You won't see me.'

'I would be ever so grateful,' she said. She shimmered over to me. She draped herself over my desk and crossed her long pale legs, one over the other. 'I remember you from the old days,' she said. 'I saw you speak once, in Munich. You were so magnetic on stage. When you spoke, I really believed in you, we all did, I think. You said Germany could be great again.' She sighed. 'But I guess you were wrong after all.'

'Germany was betrayed!' I said. 'I would have led her to victory, to, to…!' Words failed me. She smiled at me pityingly. Her long fingers reached down and curled around my collar. Her nails were painted crimson. She was a cheap whore like all actresses are. Her perfume mixed with the smell of her cigarette as she leaned close into me. Her lips were red and ripe for the picking. 'I would be so grateful for your efforts…' she said.

With an effort I pushed her away. I liked my women the way I liked my dogs, vicious and submissive at once. 'I shall see you Sunday,' I said, coldly. 'A retainer of five pounds would suffice, Fraulein Sturm.'

For a moment her eyes flashed; then she laughed, her tongue darting in between those white teeth of hers, as though she held me in contempt. She took the money out of her purse and laid it on my desk.

'Is that all,' she said.

I let it go past me. These days, I let a lot of things slide.

'Auf Wiedersehen,' I said.

She nodded, wordlessly. Then she left my office, slamming the door shut in her wake. I guess for a woman of her kind seduction was just another transaction on the balance sheet of life, like buying bread or paying off a blackmailer. I sat there for a long moment, thinking of all I had lost. Then I got up, retrieved my raincoat and my fedora, and followed her.