R.S. (Rod) Belcher is an award-winning newspaper and magazine editor and journalist, as well as an author of short and long fiction in a number of genres.

Rod has been a private investigator, a DJ, a comic book store owner and has degrees in criminal law, psychology and justice and risk administration, from Virginia Commonwealth University. He's done Masters work in Forensic Science at The George Washington University and worked with the Occult Crime Taskforce for the Virginia General Assembly.

Rod's first novel, The Six-Gun Tarot, was published by Tor Books in 2013. His novel, Nightwise, was released in August 2015, and was reissued with additional material in January of 2018. The sequel to Nightwise, The Night Dahlia was published in April of 2018.

Rod's novel, The Brotherhood of the Wheel was published by Tor in March of 2016. It was a Locus Awards finalist for Horror in 2017 and is currently in development as a television series. The sequel to Brotherhood, The King of the Road, was released by in December 2018.

Rod has spoken at numerous schools, colleges, and universities on the subject of being a full-time working writer and the craft of writing.

He is represented by Lucienne Diver of The Knight Agency.

He lives in Roanoke, Virginia with his children, Jonathan and Emily.

NEVADA, 1872. Out of the merciless 40-Mile Desert, a stranger appears in the town of Golgotha, home to the blessed and the damned. He carries with him an innocent victim of a horrible massacre and a dire warning for Sheriff Jon Highfather.

The conflict between the Indian nations and Mormon settlers has been brewing for years, and now the spirits of the fallen Indian dead have begun to rise to join in the fight. Deputy Mutt's old nemesis, Snake-Man, returns to begin a final bloody war against the Whites, purging them from the land forever. An insane U.S. General with his own genocidal agenda sees the coming conflict as a perfect solution to the "Indian problem," and, as is often the case, the people of Golgotha find themselves caught in the middle.

Mayor Harry Pratt's leadership of the town is challenged and he is threatened with the revelation of his greatest secrets, and with a betrayal that could utterly destroy him. The hungry, antediluvian terror imprisoned under the Argent Mine seeks release to devour the world through the most innocent of souls—Auggie Shultz and his wife, Gillian's, newborn. Not only is the fate of an innocent soul at stake, but the fate of all life.

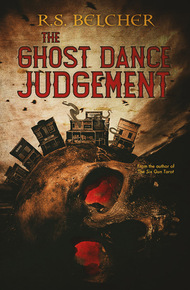

The Ghost Dance Judgement is the fourth book in the Golgotha series from R.S. Belcher, the author of The Brotherhood of the Wheel series and The Queen's Road.

I'm an R.S. Belcher fan from way back, so when the opportunity to acquire the Golgotha series came to me, I jumped on it. It's gritty, dirty, magical, thrilling, and so full of heart it aches. I'm so happy this series is continuing, and so honored to be able to give it new life in the small press world. – John G. Hartness

September 12, 1854

She ran as fast as she could, from the death at her back, but she couldn't escape the horror waiting behind her eyes. They had come before dawn, the hooves of their horses shaking the ground. It was their rumbling that woke her. It was late summer, so everyone was still sleeping in the cooler brush shelters.

They began to set fire to the rush-and-grass-covered huts as they rode by. Her father's strong hands scooped her up out of her bed. She heard many hushed and panicked voices in the darkness of the shelter. Outside was the crackle of mad fires, the blast of gunfire, and the screams of the dying.

"The damned federals," her uncle, Tooele, hissed, fumbling for his rifle. "They must think we're the damned Ute. Stupid taipo!"

Her father kissed her mother and then planted a gentle kiss on her forehead, too. He took up a rifle. He looked to her mother. "Take the children. Run as fast as you can and stay low. Go to old Cameahwait's hut out by the grazing patch. Warn them, and all of you ride as far away as fast as you can."

She smelled the acrid sting of smoke and snorted it out. There was another smell—sweet, greasy—like cooking meat. The child saw how her mother looked at her father, and she grew even more afraid. "I will meet you at the old man's place, with anyone we can free," Father said to Mother. She held him tight; the little girl clung to him, too. "Ne en tepitsi tsaa suankanna," he said to them. He didn't have to; they knew how much he loved them. "Now, run!" he said, and they did.

It was the child, her cousins, her mother, and her aunts; they did as Father had said. They stayed low and hurried toward the edge of the village. Fire capered about like a drunken vandal, making the shadows shiver and jump. The most horrible noises and smells were everywhere, smearing the air. The whites' preachers spoke of a terrible place called Hell. The child wondered if she and her family had fallen into that evil place. Mother held her hand tight as they sped away from the only home the child had ever known.

"What did we do?" one of her cousins asked softly. They watched the mounted soldiers cut down their neighbors and family as they fled their burning homes. The child saw a man running. He was on fire. He staggered, crying out in pain, and then dropped and burned silently. "Why are they doing this to us? We've done nothing!"

"Because we were foolish," one of her aunts said, the anger tight and cold in her voice. "We treated them as neighbors, as equals, as human beings. They're animals. We should have wiped them out when we had the chance."

"Hush," her mother said to her sister. "The children do not need to hear such..." She never got to finish. The child felt the hot splash on her face. Her mother's hand gripped hers tightly, squeezing. Then the thunder of the gun arrived. Mother's hand slipped loose from hers as she fell to the grass. The child looked into what was left of her mother's face. All reason left the world.

"No!" her aunt screamed as the federal cavalryman fired again and again. Angry bees whined all around the little girl. Her aunt, her cousins, her mother all torn apart around her. She saw the soldier's face; the dancing flames made him look like a co'a-ppiccih, a monster, as he cocked the lever on his gun and fired again and again. The soldier, the white man, took aim on her, the last one standing.

The little girl did not even know the word for "hate," had no idea of its meaning, but she felt something rise up in her as she felt her mother's blood dripping down her face, tasted it on her lips. The feeling consumed her like the fire devouring the homes. She clenched her tiny fists, and she screamed at the soldier, at the world, at the heavens, with the purest form of hatred ever known. The soldier clutched his chest as his rifle fell from numb hands. His eyes rolled back in his head, and he fell from his horse, quite dead.

The child looked around. She felt like she was sunburned on the inside. She was glad the murderer, the thing that looked like a person but wasn't, was dead, and she was glad she had done it. She wished she could kill them all, kill all the whites, every last one. She felt ugly for a moment, thinking such a thing, hearing her mother's voice, like cool water, trying to quench the fire inside her. Then she hugged the dead meat that had been her mother, and she was no longer ashamed of what she was feeling. She ran toward the old man's house. She never saw her father again.

Outside Cameahwait's hut, she hid in the bushes as she watched the soldiers drag the old, crippled widower out of his hut and set it ablaze. When he cursed them and shook his fist at them, they shot him in the head without a word and rode back toward the false dawn that was the burning village. She ran, ran from the fires, ran from the whites, from the madness and death. She ran and never wanted to stop running.

The days across the basin were exquisite in their cruelty. The heat gnawed on the child, devouring her slowly. Her skin was red, swollen, and blistered. Her tongue was dry and dead in her mouth. Her stomach ached with hunger, and her feet were cut and burned as she staggered through the wasteland. The nights were equally a nightmare, frozen and full of dangerous predators. Even tears were denied to her in this awful place. The girl staggered along, no idea where she was going or why she was even going on.

Then, the memory of her parents, her family, and friends would swim into her dizzy, humming, pain-filled brain, and she would remember why she would live. She was the last, the only survivor of what the whites had done, the only one who could make them pay. The rage would balloon up in her and give her the fuel for another step, and then another. She summoned the anger to move forward, to refuse to die and give the taipo final victory.

"Hello, little one," a voice said as she stumbled on through the desert. She paused and looked around. "Over here, child," the voice said again. She looked and saw a snake coiled on a stone off to her left. The snake had the most beautiful scales she had ever seen. They refracted the light of the sun into a scintillating rainbow of brilliant colors.

"Hello," the little girl croaked. "How can you talk?"

"All things speak," the snake said, "but only the wise can hear. My name is Dogoa; some call me Snake. I am here to help you. I heard your scream across the worlds. You possess very strong medicine, did you know that?" The little girl shook her head. "In time, I will teach you some secrets, but first, I want you to study with some other teachers. Would you like that?" She nodded. It was so hard to talk. "Walk in the direction of that rock way over there on the horizon that looks like a man's head. When you reach there, you will meet your teachers." The girl smiled as best she could; it felt like her skin was splitting as she did.

"Thank you," she said.

"We will meet again, child," Snake said. "Study well."

The child struggled on, buoyed by the thought of arriving at the boulder she began to call the Giant's Head. It took another day, and by the time she arrived, night was falling. She was so weak, so sick, she thought she would die.

Just past the Giant's Head was the great face of a mountain. In the rock surface was the yawning maw of a large cave. She thought she heard voices in the impenetrable darkness inside. The girl climbed the sharp rocks, her feet leaving a trail of blood in her wake. Just outside the cavern, the voices stilled, shushing each other, as they heard her approach.

"Who's there?" a voice in the gloom asked.

"Snake sent me," she said. It was so hard to make her tongue and throat work. "He said you could help me, teach me?"

"Did he?" another voice asked. "Well, isn't he a clever one. He fears to come to our lodge, afraid we will not allow him to leave, so he sends a child to harvest our secrets for him. His wit is as sharp as his fangs."

"Please," the girl said. "I'm cold, hungry, and I'm so tired. I don't think I can go any farther."

"You are close to crossing over," the first voice said, "but then it would be too late to teach you. You would know our wisdom then, but never be able to return to the sunlight lands with it."

"Why do you want our medicine, want our wisdom, child?" the second voice asked, almost accusingly. The girl tried to think, to form words, but it was so hard.

"I...everything hurts," she said. "I hurt inside and out. My memories hurt me. My family were all killed...my mother...this is my mother's blood on my face." She wanted to cry, but the only place she could was inside herself. "There is no place that doesn't hurt. I just don't want to hurt anymore."

"Pain tells you that you are alive," the first voice said. "Pain is a gift."

"I don't want the stupid gift," she said. "I don't want to be alive anymore."

"Well, you are," the second voice said, "barely, but alive. You can't come in here alive, girl."

"Let us talk with the others," the first voice said. "Wait there, girl." So, she did. She heard many voices, soft like wind, cold and sharp like stone. They argued and debated and went around and around. At some point, she blacked out. A voice, the first voice, coaxed her back to awareness.

"Child, child, awake!" it said. "We have decided to welcome you into our lodge, even though you still live. We will teach you all our secrets, all our medicine." The moon was out, bloated and scraping on the desert floor. Its light held her as gently as her mother had.

"Just know, girl," the second voice said, "there is no food here. We do not eat, though hunger gnaws at us like a rat. There is no heat here, no warmth. Your bones, your blood, will be as ice."

"I understand," she said. "I...I have nowhere else to go. What brought me to you, what kept me moving across the desert, it will sustain me."

"Your hatred?" the second voice said. "Yes. It will keep you warm and fill your belly. There are many of us here that it sustains, many who suffered the same fate as your people."

"You will be our door into the warmth of the living world," the first voice said. "We will...help each other."

"Thank you," she said, her voice weak and nearly as soft as the voices in the cave.

"Enter, and we shall begin," the second voice said.

The child pulled herself up to stand, and on wobbly, burned legs she stepped into the cave. In a moment, the cold, yawning darkness had swallowed her whole, and even the moon could not find her.