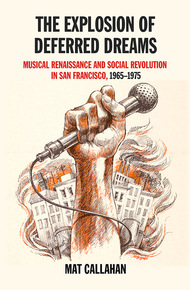

Personal Introduction

Iwas hanging around with my buddies in the schoolyard. Herbert Hoover Junior High in San Francisco, to be exact. It was Monday morning, February 10, 1964. What we were wearing said as much about

us as anything: Ben Davis or Levi jeans, Pendletons or work shirts, Keds or Converse sneakers, the basic look of kids into sports, cars, and girls. For a couple of us, this meant surfing. Though we lived in San Francisco and the Pacific Ocean is cold, we had graduated from baseball, foot- ball, and basketball to surfing, because it was cool. We were killing time before the bell rang for homeroom and up rushed some of the girls we hung out with. "Did you guys see them last night?" they said all at once.

"Who?" I asked. "The Beatles!" the girls exclaimed in unison.

I'd heard a song on the radio. I knew the name. But I'd missed the show. (I certainly didn't miss the next broadcast on February 16!) Still, I'd heard music around me all my life. My mom played Bill Haley, Ray Charles, Billie Holiday, Gene Vincent, and Elvis Presley. I had heard folk music from Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie to Joan Baez, Odetta, and Bob Dylan. In fact, The Times They Are a-Changin' had just come out and was in heavy rotation at my house. But something was going on here that didn't quite fit the picture. Instead of more music, another song in an endless stream of songs, we had a disruption, a break in the continuity. Of course, in hindsight, it is easy to see how we were being manipulated by the mass media, how the Beatles were just another in a tedious parade of teen heartthrobs, and that their appearance on Ed Sullivan was contrived by a cabal of executives in the entertainment business. But this does not diminish the fact that for us it was different. Very different.

With remarkable speed, a transformation began. I was bounced from one trajectory to another, from heading down a path common to most kids of that time to becoming a musician. Or, maybe it would be truer to say I went from having no path at all to finding one I wanted to follow. While there were other contributing factors, the moment I declared my intention to play the guitar is indissolubly bound up with the Beatles and the subsequent "British Invasion." In fact, it came within weeks of first seeing the group on television. Moreover, the controversy unleashed in my house by my wanting to play guitar is indicative of what was at stake. (I'd been taking piano lessons since I was nine, so it was not music per se that was the issue.) My father strictly opposed it. He predicted I'd start playing "that racket" (as he called rock 'n' roll), start taking drugs, and become a bum. My mother prevailed upon him to reconsider. He did, but only on the condition that I get a classical guitar. Nylon strings. No electricity. Lessons.

Of course, that didn't stop me from almost immediately taking that guitar (classical, nylon strings) and the few chords I'd learned to begin playing rock 'n' roll with a couple of my friends who, like me, had caught the bug. Now, it's hard to separate what I think I knew from what I actu- ally knew then. It's difficult to be certain I'm not imposing what my sixty-four year old memory tells me happened onto what my thirteen- year-old mind actually thought at that time. But there are a couple of important thoughts I'm quite certain came to my brain at that time and are not invented memory. One is that in a flash, sports and cars were out and music was in. The hero was no longer the athlete, the emblem was no longer the hot rod or the surfboard. And the girls? . . . Well, the cutest girls idolized musicians (musicians who played instruments, not teen heartthrobs like Fabian).

Within a few months, another eruption took place that would yet again shake me from my predetermined path onto another, one not chosen for me. I mean, I might have become a longshoreman or a dancer. That's what my father and mother were, and in 1964 most people still did something similar to what their parents did. Upward mobility? The truth was that you emulated and accepted your "station in life." That was the horizon of possibility. Anyway, my father awoke my sister and me at 4 am to drag us over to Berkeley, California, where the students had taken over Sproul Hall. It was December 3, and the gov- ernment was finally cracking down, eventually hauling eight hundred students off to jail. The same man who didn't want me playing rock 'n' roll wanted me to "see history being made" and, most importantly, to take sides with the students. On the one hand, my experience with the Beatles is one I share with millions. On the other, my experience with the Free Speech Movement is uncommon. How many fathers shook their children awake at 4 am to carry them to the site of chaotic turmoil?

Yet there I was, and I vividly remember the scene of my sister and I marching along in support of the students, as the police dragged them out of the building they had been occupying since October 1, throwing them violently into paddy wagons. Such things leave an impression on young minds; it certainly did on mine.

A bit more background is in order. My father and mother were com- munists. My father worked on the waterfront and was a member of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU). He was a militant in a militant union with a history (often retold) in which he played a part. He'd been there in the 1934 General Strike (although as a member of another union), which more than any other event had made San Francisco a "union town." He'd participated actively in every other major battle that created and nourished the labor movement in Northern California. This continued throughout the McCarthy era into the blossoming of the civil rights movement, including the sit-ins and demonstrations that took place in the Bay Area in the early Sixties. My sister participated in the famous demonstration at the HUAC hearings in San Francisco on May 3, 1960, where demonstrators were hosed down City Hall steps by the police. This marked the end of McCarthyism, because a new generation was no longer afraid.

What took place in a few months of one year, 1964, heralded all that was to come in the decade ahead and the themes with which this book is concerned: 1965–1975 in San Francisco and its environs. The two forma- tive experiences of my own youth are the seeds of music and revolution that, in the eyes of the world, made San Francisco the center of both for a brief moment in time. But some moments are forever. These are moments that disrupt the continuum, disorder the "natural" or accepted norm, and create entirely new, unpredicted conditions for social think- ing and being. They are moments in which people cease being objects and become subjects, determining the course of events instead of only being determined by them.

Three years later, the final rupture between sports and music took place in my life. I had made the high school football team, so my mother had bought me new cleats (shoes worn for football). But I was simulta- neously in a band. We played a "battle of the bands" at our high school (Lick-Wilmerding). There were only two bands in the competition— ours and another composed of close friends. We set up on the auditorium floor. On the stage above us was a band that will play an important role in this story: The Sons of Champlin. We were sixteen-year-olds. They were twenty-year-olds. Men. How that four-year difference matters. And how we idolized these guys who were already on "the road," as it appeared to us. Besides, they were a great band, and that is not just my memory playing tricks on me. Their first LP Loosen Up Naturally still sounds fresh and exciting today. There'll be more about that later on in this narrative; for now, suffice it to say that after that event, I left my uniform and my new cleats in the locker room and never looked back. From that point on, I was a musician.