Michael Moorcock is among the most influential British authors of fantasy, science fiction, and mainstream literature. His many novels include the Elric series, the Cornelius Quartet, Gloriana, Mother London, and King of the City. Moorcock has received the Nebula, World Fantasy, and British Science Fiction awards and is a Grand Master of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. As editor of the science-fiction magazine New Worlds, Moorcock was one of the progenitors of the experimental and controversial new-wave literary science-fiction movement. His nonfiction has appeared in many UK outlets, including the Guardian, Daily Telegraph, and New Statesman. A member of the progressive rock band Hawkwind, Moorcock received a platinum disc for the album Warrior on the Edge of Time.

Voted by the London Times as one of the best writers since 1945, Michael Moorcock was shortlisted for the Whitbread Prize and won the Guardian Fiction Prize. He has won almost all the major Science Fiction, Fantasy, and lifetime achievement awards including the "Howie," the Prix Utopiales and the Stoker. Best known for his rule-breaking SF and Fantasy, including the classic Elric and Hawkmoon series, he is also the author of several graphic novels.

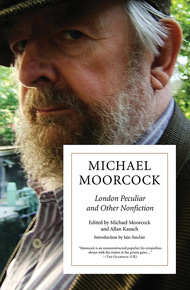

Now, in London Peculiar and Other Nonfiction, Michael Moorcock personally selects the best of his published, unpublished, and uncensored essays, articles, reviews, and opinions covering a wide range of subjects: books, films, politics, reminiscences of old friends, and attacks on new foes. Drawn from over fifty years of writing, including his most recent work from the pages of the Los Angeles Times, and the Guardian, along with obscure and now unobtainable sources, the pieces in London Peculiar and Other Nonfiction showcase Moorcock at his acerbic best. They include:

•• "London Peculiar," an impassioned statement of Moorcock's memories of wartime London. The architectural "improvements" wrought by the rebuilding of the city after World War Two brought cultural changes as well, many to the detriment of the city's inhabitants.

• • Review of R. Crumb's Genesis, previously unavailable in English, this lengthy review of the underground comic artist's retelling of the first book of the Bible leads Moorcock to address nostalgia for the sixties.

• • "A Child's Christmas in the Blitz"—An autobiographical recounting of Moorcock's childhood in wartime London, with memories of the freedom and hardships he encountered during the bombings, and the happy times he spent with his parents.

These, along with dozens more, make this a collection Moorcock fans won't want to miss, and the perfect introduction for new readers who will soon discover why Alan Moore (Watchmen) says: "Moorcock seizes the 21st century bull by its horns and wrestles it into submission with a Texan rodeo confidence."

"Moorcock's reviews and critical essays seem to me exemplary. They are never routine, never obligatory, never tired. They seem to me to be models of what a creative writer should do when producing critical prose. His writing here is always a conversation, never a monologue…we feel lucky to be listening in."

– Alan Wall, writer, poet, and professor of writing and literature at the University of Chester, UK"London Peculiar is the first full sampling of Moorcock's most important and imperishable musings on subjects both vast and various: movies and music, science and politics, the old days at New Worlds, from Philip K. Dick to R. Crumb, classics from Huxley to Pynchon, and tasty tidbits from the Tea Party to Texas barbecue. Gleaned from a full half century of opinion and outcry, London Peculiar is the work of a man of letters in the grand tradition of Orwell and Dr. Johnson. It's Old School and it's all you need to know about Tomorrow."

– Terry Bisson, Hugo and Nebula award-winning novelist"Moorcock's writing is top-notch."

– Publishers WeeklyThe Man on the Stairs

Introduction to Michael Moorcock

I could never quite persuade myself that there was any such human entity as Michael Moorcock. I mean in the sense that you could touch him, or talk to him, or sit down with him for a meal at which the seamless stories, the astonishing anecdotes, the myths and memories, would ravel and unravel, lap and overlap like swirling, contradictory, sediment-heavy Thames tides. The man was too fecund, too prolific, in too many places, high and low culture, for me to believe that he was one person and not a Warholite factory or a nest of Edgar Wallace typists. Comics, sombre periodicals, political pamphlets, rock shows, numerous TV and fanzine interviews: Mike was a shape-shifter, a character actor in the labyrinth of his own fictions. He was Sydney Greenstreet, Robert Morley, Akim Tamiroff. And the always reliably untrustworthy Colonel Pyat. He played so many parts in this complex, many-chaptered, cliff-hanging serial of a life that readers, panting to keep up, were left dizzy and breathless by the rush of language. But somewhere beyond the Casablanca cafés, the arms dealers in the lifts of Cairo hotels, somewhere behind the smoked glasses, the Bedouin headgear, is a well-setup Englishman with a proper pen in his shirt pocket and a sturdy notebook tucked into his linen jacket. A person quite capable of writing with the precision and clarity of a coin-per-word professional. Nobody knows better than Moorcock how to manipulate the white spaces, how to compose pages so slick with narrative devices that they do the turning for you. Our trust has been won by the confident and breezy tone of the author's address; very soon, we are walking in his sleep, navigating by the architectural markers of a fantastic city much like London. Moorcockian prose is discovered, not prescribed or advertised. You will come across it like a monument in a park you thought you knew. His books seem to have been there for generations, waiting on readers with the right password: affection. Affection for self, for a remembered and ever-present past, for place. For people. The bruised and the blustering mob of individuals.

The trappings of style are just part of a magician's kit, like the conjuring tricks of Orson Welles, the pass of a scarlet cloak disguising the authorship of Citizen Kane and an afterlife of sherry commercials. That Moorcock beard has a genealogy of its own: Rasputin, James Robertson Justice, Robert Newton, Richard Hughes, Augustus John. The beard's cultivator is revealed as pirate, clubman detective, Russian prince, Crowleyite magus, desert prophet. But, underneath those curling barbs, is a handsome, seductive presence: Michael Moorcock, the absolute storyteller of our time. An author whose genius lies in the range of his sympathies, the depth of his affections (and his piques). Mike is intensely local, and loyal to the ground of his upbringing in South London, and also comfortable in the world at large, in Texas, Finland, Istanbul, Majorca. All those fabulous harbours and Circle Squared ranches. The Kensington apartments from the Arts and Crafts era. And the hidden Holborn yards of a customised geography. The London Peculiar of Moorcock initiates. Those strange creatures able to step out of literature and into the streets. Psychic detectives healing the wound in society, taking on the eternal battle with the forces of darkness, politicians, developers, undying vampires.

Moorcock is the essential conduit between Beowulf songs and sagas of mead-hall poets and the banjo-plucking, cattle-drive yarns at campfires of the American West. He shifts, effortlessly, from the established forms of the Victorian and Edwardian masters of narrative to the fragmentation of high modernism. I am stopped by the quiddity of voice, that point of recognition for any good writer. You know, from the confident rhythms of the first sentence, you can trust the person who is spinning this tale. Trust him to trick you, lead you astray, excite you, carry you right back to that good place where there is a suspension of disbelief and the closing down of critical faculties for the pure pleasure of wanting to know what happens next. Both author and actor, Moorcock is the designer of a complex Word City in the last era when readers have the stamina and wit to undertake a journey through such a vast and unknowable concourse. A voyage during which they understand that they must allow themselves to be swept away by oceanic surges of inspired prose.

London Peculiar is the chart of a writer's odyssey through time and space, from the fertile dreams of childhood, through encounters with teachers and fellow visionaries, to heartfelt polemics and tender tributes to the immortals with whom Mike has shared tea and sympathy. All dues paid, the labyrinth of this imagined city is illuminated in every ditch and twitten, from hard-drinking journalists' pub to some enclosed religious order, where high walls mask the entry to a subterranean world so improbable that it has to be true. Readers coming to the anthology London, City of Disappearances (2007) were as inclined to believe the mythical gazetteer of Michael Moorcock as the authentic research undertaken by the historian Sarah Wise. I'm sure there are folk out there now, tapping at bricks, poring over ancient maps, trying to find their way into the Hearst Castle of Ladbroke Grove or the tunnel beneath the Convent of the Poor Clares. Moorcock's London is a multiverse, curled back on itself, traumatised by war, papered with shilling-shockers and odd-volume three-deckers, enlivened and animated by collisions between the real and the fabulous.

Angela Carter, another magnificent writer from the wrong side of the river, presented Mike's literary terrain as 'a vast, uncorseted, sentimental, comic, elegiac salmagundy'. The scale, richness and diversity, does that to commentators; adjectives spill promiscuously as we struggle to hint at the boundless energy of the original. Carter saw the work as coming from a zone 'so deeply within a certain tradition of English popular culture, that it feels foreign, just as Diana Dors, say, scarcely seems to come from the same country as Deborah Kerr.' And this too is on the money, no one was better placed than Carter, the white witch of Streatham, a celebrant of rouge and gin and talcum powder, and the best kind of bad behaviour, to equate Moorcock with an actress who could live a life of tabloid sensation and, at the same time, deliver the broadest of lowlife comedy and the scrubbed-down realism of Yield to the Night. Moorcock's sprawling, sharp-tongued old ladies, Mrs Cornelius and the rest, are worthy of Angela Carter. He has been, for many years, a champion of his friend Andrea Dworkin and a promoter of W Pett Ridge's wild child of the streets, Mord Em'ly. (Both find their place in the pantheon of London Peculiar. Along with a tribute to hardboiled novelist, screenwriter, and author of influential works of science fiction, Leigh Brackett. Only Moorcock could discuss Brackett by way of a 'Spanish-speaking Swede', encountered while hitchhiking through Germany. A person who recommends the stories of Borges, before the Argentinean has been published in England. Moorcock, of course, met both Brackett and Borges.)

I was in the process of deprogramming myself, after emerging from school and university, when Jerry Cornelius began his seductive dance across my London consciousness. I was a dim provincial, originally from Wales and, more recently, from a Dublin still unravished by the Celtic Tiger, when I noticed Mike's dandified, Carnaby Street assassin in the comic strip drawn by Mal Dean for IT, the underground newspaper. As much countercultural impresario as author, Moorcock would appear in the strip, offering jocular asides and winking at the audience. Dean, who drew on Tenniel and Heath Robinson, as well as jazz and movie lore, and the German satirists of the twenties, was married to the poet Libby Houston. Houston sometimes performed with the travelling poetry circus of Michael Horovitz and Pete Brown. It seemed, from where I was sitting out on the eastern fringes, that Notting Hill was the only show in town. It was, among other things, a famous street market drawing in tourists and outsiders. The district held on to echoes of the novels of Colin MacInnes. And, behind these, the vegetal stink of Rotting Hill by Wyndham Lewis. And faint whispers of The Napoleon of Notting Hill by GK Chesterton. William Burroughs, in his brief, hallucinated English exile, lived in a small hotel on the edge of this area. Moorcock brought JG Ballard, his New Worlds collaborator, along to see him. The children of the Raj, the private income gypsies, the psychedelic hustlers, and the indigenous traders, working folk and layabouts who had been there all along, rubbed shoulders with rock musicians and, occasionally, with Michael Moorcock, in pubs where legends of place cooked and simmered. The end of the era was signalled by the Nicolas Roeg/Donald Cammell film, Performance—which was, among other things, an unconscious salute to the Jerry Cornelius template. (Even if those teasingly titled Cornelius books, A Cure for Cancer, The English Assassin and The Condition of Muzak, were still to be published.) It wasn't that Mick Jagger, the sequestered rock star of Performance, was the inspiration for Jerry Cornelius, but, rather, the other way round. Dartford's Sir Michael was a gaunt Xerox spectre, his stellar career anticipated and resolved in Moorcock's dazzling fictions. Which are always intercut with melting news, headlines of the moment sliced like Cubist cut-ups.

It seemed, in the mid-sixties, that Moorcock had the keys to the kingdom. He swayed and drifted through temporal vortices, channelling postwar bohemians, Dylan Thomas and Mervyn Peake, recognising Burroughs and Borges as mentors and peers (good sources to steal from), nodding to Angus Wilson in the British Museum, sitting in with skiffle groups in Soho, anticipating new waves of hopeful and ambitious authors, a friend and supporter to China Miéville and Tony White. And in all of this activity, with all these avatars and off-cuts, the fundamental reality was a man in a room with a typewriter. A man who has now assembled, like a market trader, a spread of objects, startling or familiar, as a form of refracted autobiography. 'Here I began, look at my fleet of miniature battleships. Step out into Christmas suburbs that do not fade or change their season. Follow me into bazaars that never close. Come closer and I'll tell you about Arthur C Clarke's curious birthday party in Tottenham. About adventures in the Hollywood night. And cruises on Russian liners.'

London Peculiar is a lovely record of the evolving tastes and fancies of the most sure-footed and generous author of his era. This book, like the blockbuster marvel Into the Media Web, edited by John Davey for Savoy Books, is an index of numerous careers, starts and detours, unlikely connections. Document morphs into fiction, fiction into legend. Moorcock is the only contemporary who could have rubbed shoulders with George Meredith, PG Wodehouse, Jack Trevor Story, Edgar Rice Burroughs and William Burroughs. And yarned with them on equal terms. He is a genuinely popular writer, in several genres, who has also produced such literary masterworks such as Gloriana, Mother London and the criminally undervalued Pyat quartet.

Towards the end of my active phase as a used-book dealer, I remember carrying out boxes of stock from the offices of a publisher who had decided to 'rationalise' the archive by dumping file copies going back generations, in a gesture of mindless cultural erasure (by which I was happy to profit). And as I staggered down the stairs, Michael Moorcock, in his fancy waistcoat, fingers flashing with rings, ascended, to become at once the centre of an excited buzz at a launch party. Literary London paid homage to a man who, little did they know, would soon be away on his travels. Never to return. As other than a passing rumour, a presence on stage or in some favoured Indian restaurant or fish bar.

Before this, I had seen Charing Cross Road brought to a standstill by a queue snaking out of the Forbidden Planet shop, which was then on Denmark Street, and right back, almost to Cambridge Circus. Furtive figures stooped under the weight of carrier bags filled with Moorcock multiples. Dealers. Ghosts. Hardcore fans up from Surbiton or Pinner. All of them soliciting the validation of that lavish, free-flowing signature. Mike was a dedicated defacer of title pages. I knew collectors who built up libraries of his playful (and clearly admitted) forgeries, when he livened up first editions of science-fiction worthies of the old school by offering presentation inscriptions on their behalf. Mike also kept street dealers such as myself awake by handing out many-sheeted wants lists of the lost volumes required to inspire and inform any one of the half-dozen books he'd be working on at the time.

It was a great moment for me when I met the Moorcocks, Mike and Linda, at the home of my Paladin editor, Nick Austin. Like all the other shuffling penitents on Charing Cross Road, I had my copy of Mother London personally inscribed. Soon after that, I began to meet Mike, and his friend Peter Ackroyd too, for lunches at which we rambled across the subject of London: as topography, gossip, memoir. Ackroyd, I felt, had an astonishing ability to absorb what he needed for the project in hand and then to brush aside matters of detail, names, dates. Not his concern. His sense of the city was of eternal recurrence, certain qualities assigned to favoured areas, such as Clerkenwell, Limehouse, Southwark. A conservative prospectus highly attractive to those who dealt with riverine heritage. We were being sold a consoling version of the past, gothic and occulted, to dress sets where new towers were mushrooming. The Ackroydian library, curated by 'Cockney visionaries' (from Blake to Moorcock), made London into a glorious theme park of approved history. Moorcock's sets and characters were quite different, animated by something that happened, an incident, a rumour. London was held in affectionate exasperation as she tried to live up to her own legends: the fire-storms of German WWII bombers bringing together a tribe of sleepwalkers, ranters, spivs, and damaged urban poets, who stitch a memory blanket for survivors.

London Peculiar is a personal audience with Moorcock. He tells stories, terse or at length. He reminds us of people we used to know. And he encourages us to take a look at those we might have missed on their first appearance in print. Journalism sits agreeably alongside fiction, diary with essay, obituary tribute with informed analysis. There is even a bibliography offering a glimpse at a fraction of what Moorcock has produced in the regular days of work that he describes, a routine that allows time for hairy escapades, travel, and meals with friends and loved ones. If there is such a person as Michael Moorcock, this might be a good place to search him out. Here is a magical staircase on which you can pass the same person, coming down, at every turn.

Iain Sinclair