Brian Riggsbee is the creator of Retro Game Books and the author of The Complete History of Rygar, Video Game Maps: NES & Famicom, and Pixel Art: Metroid. As a former game developer he contributed to games such as Medal of Honor, Gods & Heroes, and numerous Disney games that continue to haunt his nightmares. When he isn't writing he can be found watching basketball, playing retro games, and eating massive quantities of pasta. Brian lives in San Francisco with his wife and boy.

Brian Riggsbee is the creator of Retro Game Books and the author of The Complete History of Rygar, Video Game Maps: NES & Famicom, and Pixel Art: Metroid. As a former game developer he contributed to games such as Medal of Honor, Gods & Heroes, and numerous Disney games that continue to haunt his nightmares. When he isn't writing he can be found watching basketball, playing retro games, and eating massive quantities of pasta. Brian lives in San Francisco with his wife and boy.

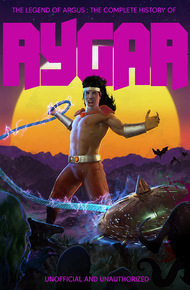

From Argool to Zane, The Legend of Argus: The Complete History of Rygar is a comprehensive look at the history of the games, characters, and world of Rygar (AKA Argus no Senshi). Included is the history of every Rygar game and port, an interview with Rygar Amiga developer Graeme (mcgeezer) Cowie, Q&A with ROM hack developers, fan art from 50 artists, action figures, mods, cover bands, classic ads, arcade flyers, speedrunner spotlight, trading cards, magazines, guides, and reviews of the era. With a Foreword by Kurt Kalata, Editor-in-Chief of Hardcore Gaming 101.

Brian Riggsbee's complete history of Rygar delivers precisely what the author promises: a deep dive into the making of every Rygar game and port, along with a trove of fascinating bonus material such as interviews with ROM hackers and speedrunners, flyers from the franchise's arcade days, and reviews and guides from its heyday. The book is itself a monument to one of the greats that many have forgotten. Riggsbee aims to remedy that, and does so expertly. – David L. Craddock

"It's the kind of thing you might expect from a book about Mario or Samus, but not so much from one about a semi-forgotten shirtless hero carrying, as foreword author Kurt Kalata calls it, "a gigantic spiked yo-yo." And it's fantastic."

– Matt Leone | Special Projects Editor, Polygon"It digs into some pretty obscure versions [and] was an interesting read."

– Jeremy Parish | Media Curator at Limited Run Games and Host of RetronautsA New Adventure

While the Famicom and NES version of Rygar (Warrior of Argus: Extreme Great Charge in Japan) shares the basic ingredients with the arcade original — a Diskarmor-wielding hero who travels through a desolate world fighting an army of monsters — it uses them to create something very different. Like when Bionic Commando, Strider, or Ninja Gaiden transitioned from arcade to 8-bit home console, Rygar too evolved from a repetitive slasher into a much deeper experience. Perhaps Nintendo was asking for higher quality with their third party games, or perhaps developers just saw more potential in the home console experience.

Whereas the arcade version of Rygar features a linear level progression, on NES the game encourages the player to return to prior areas. RPG elements were introduced, with experience points that boost the attack power and health of the hero. A brand-new spellcasting mechanic was added, with Mind points that replenish during play by defeating and looting foes. As with Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (released three months prior to Argus no Senshi: Hachamecha Daishingeki), there are NPCs to assist the player, as well as two different gameplay perspectives: While most areas appear in a side-scrolling view, transitional areas feature a top-down perspective. With no passwords or built-in save feature, Rygar asks players to conquer its sprawling adventure in a single sitting, but unlimited continues at least make this feat feel possible.

First Impressions

Upon pressing start, the hero appears and an epic melody boldly squeals out, with an intro riff that rolls into a dense musical composition. You're in a barren wasteland, just a small blip in the vast unknown. A giant orange sun hangs in the background, and that celestial orb remains center stage as you begin to sprint across the uncharted landscape. Obstacles and monsters appear to test your agility and might as you, the warrior of Argus, leap with ease, dancing over your foes. When you transition into the next area, the depth of this world — and your adventure — begins to be revealed as the music shifts and branching paths begin to make themselves known.

All Day Play

The ability to resume your progress after powering the NES back on was not always an option for games of this time. Classics like The Legend of Zelda or Metroid had battery-powered save features or password systems, both of which allowed the player to pick up where they left off. Despite being a long and grueling game, Rygar lacked such a convenience. For most, this meant an incomplete experience, an ending that was never to be reached. For others, like myself, it meant practicing, exploring, and learning before the inevitable big push, the day dedicated to powering through the game end to end. This might even last many days, if they dared pause and let the NES bake overnight (at risk of a power outage or mom turning the system off). As with other NES games, I shared this experience with my neighbor, taking turns after each death and strategizing before our next attempt. Today, lacking a save feature for a game as long and involved as Rygar would be practically unheard of. It makes one wonder: If Rygar did offer the ability to save your progress, giving more players the opportunity to reach the deeper depths of its world, might it be remembered more fondly?

Metroidvania

The exact definition of Metroidvania is a bit disputed, but the most commonly agreed upon factor is that a Metroidvania game has a non-linear style of gameplay. In many cases, this equates to traveling through an open world, acquiring items that will open up new paths that branch off from previously visited areas. Castlevania: Symphony of the Night is one of the most popular and referenced Metroidvanias, and exemplifies the genre for most due to its deep RPG elements, stellar combat system, expert character design, and massive network of rooms to explore.

While the term Metroidvania comes from the two franchises that cemented a particular style of non-linear gameplay, it's noteworthy that Rygar was already experimenting with concepts that would later define the genre even before Metroid and Castlevania II: Simon's Quest. With Metroid releasing just four months after Rygar in Japan, it'd be foolish to make the argument that Rygar influenced Nintendo's Alien-inspired sci-fi adventure. Yet Rygar nonetheless feels like a step along the path to games like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. It seems like there was just something in the air in the world of Famicom development, pushing designers to explore what was possible beyond the scope of arcade-like experiences.

When it comes to Rygar, the game fits neatly into the most basic definition of a Metroidvania: A character that explores a non-linear world, collects items and power-ups, increases his attributes, and backtracks in order to make use of the tools. Markers such as grappling hook points tease the player of future areas to revisit. Hints and clues are scattered across the world, coming in the form of helpful NPCs.

So why is Rygar so often forgotten in the conversations around the early Metroidvanias? If Rygar had continued to have sequels in this style, might we be calling these nonlinear games Rygarmanias today?