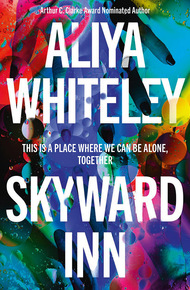

Aliya Whiteley's strange novels and novellas explore genre, and have been shortlisted for multiple awards including the Arthur C. Clarke Award, BFS and BSFA awards, and a Shirley Jackson Award. Her short fiction has appeared in many places including Beneath Ceaseless Skies, F&SF, Strange Horizons, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, Lonely Planet and The Guardian. She also writes a regular non-fiction column for Interzone magazine. She lives in West Sussex, UK.

Drink down the brew and dream of a better Earth.

Skyward Inn, within the high walls of the Western Protectorate, is a place of safety, where people come together to tell stories of the time before the war with Qita.

But safety from what? Qita surrendered without complaint when Earth invaded; Innkeepers Jem and Isley, veterans from either side, have regrets but few scars.

Their peace is disturbed when a visitor known to Isley comes to the Inn asking for help, bringing reminders of an unnerving past and triggering an uncertain future.

Did humanity really win the war?

I fell for Aliya's writing years ago, with one of, and I'm not kidding, most disgusting and hilarious stories I ever read – and she'd only gotten even better since. Her latest is the best kind of science fiction – you're in for a treat! – Lavie Tidhar

"When it comes to misdirection, Aliya Whiteley is the very devil."

– The Times"Whiteley's trademark subtle surrealism shines."

– Publishers Weekly"Skyward Inn feels like an instant classic of the genre."

– The Guardian"Whiteley explores questions of identification, attachment and belonging, tying everything together in a wonderfully surreal and weirdly uplifting denouement."

– The FTThey've drunk their drinks and sung their songs, and it's time for them to head for home. I wave them off, turn my back on the first streaks of light in the sky, and close the door to the inn.

Isley says, his voice soft and self-mocking, 'Alone at last.' He says it every time we've got the place to ourselves. He practised his English on Tung Base, millions of miles away, by watching old films, and sometimes I can imagine the kind of drama he thinks we're in. The lamps on the walls are burning low. I love this time, time between times. It's a soft grey bleed from night into morning.

'Pour,' I say. I walk back to the bar and pull up the well-used stool with the cracked leather top. The smell of the heaped glass ashtray between us is very strong, and I slide it to one side. The ash settles into the grooves patterning its rim.

The glasses Isley pulls out are his good ones. We're getting a taste from the best bottle. I smile when I see him lift it from under the counter—an automatic reaction to that conical shape, in the orange clay from his world.

'Special occasion?'

'You don't remember?' He pulls out the cork with his thick, blunt teeth and tips the clear liquid into the glasses. 'I thought you remembered everything.'

It's the thirteenth of September. It's not any anniversary I can think of, and we have drunk to them all.

'It's seven years since I first told you I love you,' he says, and clinks his glass against mine.

That was in this bar, and I was sitting on this very seat. His chin trembled when he said it, and I remember I thought only that I wanted him to not be scared of what comes next, of where love leads.

'I told you I loved you too,' I say. 'I didn't even have to think about it. The words came easily.'

'Are they still true?' He frowns into the glass he holds just below his mouth. When he drinks, the moment will be over with, done. It's impossible to feel bad with Jarrowbrew in your body.

'Everything I say to you is true,' I tell him, but it sounds unreal, so I add, 'At least, I try to make it that way.'

'You do try,' he agrees, 'and that's why I still love you now.'

It's a good thing to drink to. We drink.

Here it comes, here it is: the sweetness I associate with fields, and the depth I think of as the sea. The soft light it brings to my mind belongs to the sky of Qita. What do the regulars at our inn see, feel, when they drink brew, I wonder? Most of them have never been off this planet, or even out of the Westward Protectorate. They must translate it into their own experiences, which are no less potent, I'm thinking. Just—miniaturised. Pin-sharp, unshakeable, mired in the thick grasses of the West Country moor.

'Jem,' he says, 'You know Toulu? Where the rock divides? Did you ever go there?'

'I did.'

'Did you look at the fossils? In the heart of the rock?'

I fix Isley with my patient eyes. 'You know I did. I went to all the places, with my leaflets.'

'Yes,' he says softly. 'Your leaflets. Your letters of peace, from Earth to Qita. You put them up everywhere you went, for us to find.'

He sounds so sad. I give him what he wants, and what he never asks for, directly: a description of his homeworld. It's changed, of course. But here, right now, in my words, it hasn't. Not for us, on our different sides, meeting in the middle.

I say:

I remember Toulu.

Your creatures from your past, your fossils, are only shapes in old stone, so very far away. I put my hand on their outlines. I can tell you evolved from swimming organisms with long limbs and large domed heads; these were weighty bodies, leaving ribbed regular marks upon the rock, suggesting a shell. Your people have lost the shell through the path of time, just as humans did. Some things, we all have in common.

Toulu—the rock itself, a vast standing stone in a lake—was split by a great force, perhaps a natural event like lightning, leaving a clean edge. That, too, happened a long time ago. So there has been at least one act of violence on your gentle planet. A cataclysm of its time, for those creatures that lived near it; around it.

I was one of the first visitors to that place, and I was keen to suck up experiences of Qita, to better do my job of bridging the gap between us. When I saw it, I thought of how similar and how different it was from the earliest paintings made in caves here on Earth: Chauvet, Lascaux, Altamira, long cordoned off from casual visitors. They are far too precious to be worn down under the weight of endlessly curious humanity. Toulu is free, and open. I could never explain to anyone on this planet what it is like to have that genuine, amazing sight all to myself.

I spent time absorbed only in the marks of those long-dead bodies, frozen in the act of their own movement. They swam in perfect fractal patterns, proving—what? That Qita was always a planet of order, even down to its basic organisms?

I don't understand, even now. I never have.

I did not want to hang my message upon it, but that was my job, so I went ahead anyway. I used the nail gun to attach the leaflet. Not to the rock itself. To a nearby tree. But as I punctured its bark I thought: is this tree less beautiful? How long has it been standing here, keeping the rock company? They're an old married pair, and if I wound one, that injury will be mirrored in the other.

I put these thoughts down to my own ridiculousness, finished my job, and returned to the base. I made my report, and the regular tourist rides out to Toulu started soon after. Military tourism keeps trouble at bay, I was told.

'Jem?' says Isley, into the silence that follows. Jarrowbrew telescopes time as well as distance. It is, no doubt, morning proper by now. If I stepped outside, or moved aside the curtains, I would see it.

'Yeah?'

'Go to bed.'

'You too,' I tell him. To our own beds. Our separate rooms.

'I'll clean up a bit first.'

'Right then,' I say, and his timing is exactly right, as usual, for the glow of the Jarrowbrew has faded, and I have no energy for doing the tasks of a tomorrow that has already become today.

'Two more pies, one with mash, one with chips,' I tell Isley, through the hatch.

It's my job to be out the front, pulling the pints, listening to the conversations. The talk is always the same and forever mutating, growing to fit the crowd that listens. It might start with one deer, spotted on the moor, and then it becomes a magnificent stag, the biggest ever seen in these parts. More ears engage, and then it's two stags, and by the end of the week Bill is telling everyone I was close enough to see their nostrils flaring and I wonder where he'll go from there. Will he ever touch one, in his growing story? Will a stag come and eat from the palm of his hand?

They're laughing again, as Isley starts preparing the order. He was reluctant to cook tonight. Perhaps it's a reaction to what happened last week. I don't want him touching my meal said one of the farmers from the next village along, passing through on trade, and everyone at Bill's table stood up and stared him down, in silence, until he left.

We'll have none of that here, said Bill. They're a good bunch.

'Hey,' says Isley, through the hatch. 'Pies.'

There's laughter from the bar again. The stories are coming thick and fast tonight. They are inching and evolving around me.

'Come out and sing with us!' shouts Bill Sedley through the serving hatch, after they've eaten and drunk, and drunk again. They've been singing "Harmless Molly" for what feels like hours, and I know Isley hates the arguments they have about which version is the right version, and the ensuing cacophony they create, but he comes out to a cheer and accepts their claps on the back with good grace.

They are allowed to touch him.

Still, I smile along as they launch once more into the story of a man who must leave his love to go to sea and fight the Spanish, and Isley joins in with his clear, cool voice. He's a wonderful singer. The locals don't know it, but that comes from the Qitan language, which is itself a song, beautiful to listen to. Preferable to the ruination of "Harmless Molly."

'You're a good lad,' says Steve Purley, at the end. 'Isn't he? He's a good lad. Fits right in.'

There's a high compliment indeed.

'Time, gentleman!' I call, and they complain, but it's good-natured moaning as they make for the door.

'Tell me about growing up with your brother,' says Isley, when the last of them has gone. He's poured out two glasses of the standard brew for us, the one he makes by the gallon in the cellar, leaving the good stuff under the counter tonight. I don't mind. Not every night can be bathed and put to bed in the best memories.

'Why do you want to hear about Dominic?'

'He's a powerful man and I need friends.'

'You have me,' I tell him. 'Cosying up to a local official won't do you much good, anyway. He can't change anything. All he wants is to look responsible for it.'

'Was he always that way? Keen to… take responsibility?'

I shake my head. I don't talk about the here and now on Jarrowbrew, even the weak stuff. I don't talk about childhood, either. Nothing before Qita, and nothing after.

'Don't they say that the oldest sibling is keen to take responsibility?' Isley persists. 'They can be the bossy one.'

'How do you know what siblings can be like? I thought Qitans didn't have any.'

'Who told you that?'

'You did.' I can't be certain. Maybe I simply assumed it. Qitans have always seemed so separate to me: islands of their own. 'Or maybe it was Coach.'

He considers this, then says, quietly, 'I've got many siblings.'

This is new information, and I find that not only do I not want to talk about my family: I also don't want him to talk about his. The ties and losses on both sides. I thought we had an agreement not to even start down this path. The Skyward is the place where we can be alone, together. I don't want the past beyond our own timeframe to intrude. 'Let's drink to coolness,' I say, quickly, and we clink our glasses together, and drink it down. That will put an end to this line of conversation.

I have to conjure up a memory of Qita, quick, if I want that, so I say, 'This batch isn't a patch on the stuff in Langzin Square, is it?'

'Isn't it?'

So I tell him again about market time.

We were both there, but in different times, from different angles. I speak of it the way I remember it, mingled with the way it was told; the rules were explained to me before I arrived because it was not the kind of place one could understand simply by looking and listening. It made no sense unless you knew how to see it, make sense of it. So I came with foreknowledge through Coach.

Coach was the device implanted in my head by the Coalition, providing for all my information and entertainment needs—how did Coach already know about Qitan life, I wonder? Qitan workers on the base? I had Coach removed years ago, at the end of my contract, but it has left its ghosts. Sometimes I still ask a question to it, expecting an immediate answer to pop into my brain. Living that way can be addictive. I think maybe it's why I hate questions so much now. My thoughts need to be my own. Mine, and in the wake of Jarrowbrew, as I talk to you of our past, yours.

A high stone wall surrounds the square, in the centre of a bustling town. Traders queue at the start of each day to receive identical rectangular slabs from the market keeper. They're cut from the same stone as the walls; each one has a supple, shiny strap attached to one side, hung around the neck to balance the slab on the chest, creating a ledge upon which items for sale can be placed.

When all the slabs are taken, the keeper takes up a weighty metal cylinder and swings it in a circle overhead. The loud peal of a bell pours forth. The traders are then admitted, and they walk clockwise inside the walls, while prospective buyers sit on the central benches, in the shade thrown by the central cluster of fruiting trees.

The small surface area of each trader's ledge means that Jarrowbrew is the most popular product to sell. A tall, transparent container is placed in the centre with glasses around it, in a design said to mirror the market itself. Often Jarrowbrew has colour or flavour added to it, and the glasses may be individually decorated. The displays can be elaborate and ingenious, but does that mean the brew is better? Not necessarily, but then, this is all moot—at least in ways that I, a human, an outsider, can understand. The most inexplicable part to me is that no money changes hands. Locals insisted trade is the concept that explains Langzin Square best, but this is not supply and demand: when the glasses have all been used and the container is empty, the trader must leave. It does a trader no good to offer a more or less popular product—not that they strictly offer it at all.

On the day I visited, I was prepared. I did not approach the traders, which would have been considered impertinent. I sat, in a shaded spot, and waited for one to come to me.

It took an age, and I felt so many eyes upon me. It was their chance to, at the very least, humiliate me. For what I was, for what I represented. But then a trader came to me, and said the words I had been hoping to hear. He spoke in his own language, then in Chinese, which I translated to English:

I give if you take.

He was tall, and his chin was even bigger than the usual, probably from years of wearing the strap upon it. His Jarrowbrew was plain, his glasses small and undecorated. The Qitan on my left shifted and tilted his head; I supposed jealousy on his part. I guessed this trader was well respected.

What made him trade with me? To learn his classic phrase in other languages, for just such a moment? What could I give him in return?

To trade is the choice of the trader, not the necessity, in Langzin Square. It is the business of hunting, by their own criteria. Do they look for those who seem in most need of their product? Or those who might reciprocate one day? That, it seems, is their decision to make.

I replied.

I am yours and you are mine.

A glass was poured, and given. I drank down the brew, and dreamed of a better Earth.

I don't think I'll ever taste anything as good again. But sometimes, Isley, sometimes, after a long night on my feet, and the thought of my son's disinterest in me biting, your best stuff comes close.

I stop talking.

'You know,' says Isley. 'That's not strictly accurate. About the ledges.'

'What bit?'

'The traders are meant to leave the market when they're sold out. But here's the thing—they have accomplices. Helpers have worked outside the walls to make very small tunnels, slanted downwards, through which Jarrowbrew can be poured. They wait outside and at a set time a trader stops by their hole, and refills their flask. Everyone knows it, and it is tolerated. It's… amusing, isn't it? We all think so.'

I picture the traders, surreptitiously putting their flasks to the walls at their designated spots, filling up once more. I had missed that entirely when I was there, although I had watched them for hours. But then, I wasn't looking for it.

'It's funny,' I say, 'how you can learn the rules of a place, but not which rules are okay to break.'

'You couldn't have broken them. It wasn't your place.'

I wonder if Isley is aware of the double meaning of what he just said.

'If everyone's been busy making holes for generations, doesn't that mean the walls are weakened?'

'Of course. The square is in danger of collapsing. Last thing I heard, the Coalition awarded a grant to try to repair the "damage". A report concluded that some unknown burrowing creature had attacked the structure.' He laughs, and I laugh and how ridiculous everything seems, right now, in the way our two sides of information have just come together.

'Who told you that?' I ask. 'About the Coalition?' Outside news can be very hard to come by in the Western Protectorate.

'Go to bed, Jem,' he says, and takes away the glasses to wash them up.

I wake, and for a moment I don't know what I've heard. Then I place it—the squeak of the hinge of my bedroom door—and I know he's pushed it open, just a little.

'You okay?' I ask the darkness, in his direction.

'I did knock.'

'It's fine.'

'Can I come in for a minute?' Isley says, low and soft.

'Yeah. Come in.' He moves towards me, leaving the door open, and sits beside my hip, on the edge of my single bed. He's no more than a shape in the night. I sit up on my elbows, lean towards him. He has always been very clear that there can be nothing physical between us, but I've imagined moments like this: the possibility of this. Finding a way to be compatible.

'I have to tell you something,' he whispers.

What kind of things belong to this moment, between dreams and daily schedules? Am I hoping for certain words?

'Okay,' I say, taking his tone, matching the mood.

'I would ask you if you can keep a secret, but I know you can. You do. Keep your own secrets, I mean. Now I need you to keep one of mine. Is that all right?'

'It's fine.'

'There was an accident.'

But his voice is so casual. I push myself upright and lean back against the iron bedstead, icy through my thin pyjama top. My eyes are beginning to adjust to the darkness; he's still dressed in last night's clothes—the surfing tee-shirt, the loose trousers. He smells of the bar, and his curly hair hangs loose in those natural thick ringlets, around that large, curved chin. I can't focus on anything else.

I touch one of the ringlets. It's coarse and slippery. I hear his breathing.

It's so easy to touch him. I should have reached out years ago. His words are trickling through me. What did he say? There was an accident. Finally, I feel myself coming around to wakefulness, to possibility. To fear.

'Is it Fosse?' Please, not Fosse, not my son.

'No, no, it's me.'

'You're hurt?' The thought of that is unbearable. Don't let there be damage, not to him, to us.

'No, I just mean—it's here. Nothing to do with your kind.' Does he mean my family? Or my species? 'Can you come downstairs? I can't do this here. You'll want to get dressed.' He stands up and walks out, leaving the door ajar, and I dress with that crack in the door taking up all my attention, as if something unbidden might put its ugly eye to it, or slip through, if I'm not careful. I must guard against such disasters. I dress in my woollen jumper and loose jeans, over my pyjamas, then put on thick socks to keep out the cold of the stone floor. And only then do I dare to widen that crack in the door, and follow him down the stairs.

He has lit all the candles, snug in old wine bottles on the tables, and the fire is burning low. Isley is sitting at the small table nearest the fireplace, and he is looking at me.

'What is it?' I whisper.

He shifts in his seat, just a little, to one side, and only then do I realise that he's not alone.

A man sits opposite him. Or a woman. A Qitan. I should have seen it straight away: the thick jawline, the tiny nose. Blue blush to the skin. Another Qitan, here. She turns to look at me, features alive in the glow of the embers. The voice is high and light when she says, 'I'm so sorry, I don't mean to be difficult.' The meaning of the words as much as the tone makes me evaluate her as female. Crazy human assumptions.

'How are you here?' I ask.

'I can't get back.'

'You came by ship? How could a ship get through the Kissing Gate without being spotted?'

'It's very small,' says Isley. 'It's the suit. It's broken now. Something went wrong.' He gestures to what she's wearing; it's an orange one-piece outfit, resembling a boiler suit—worker's clothes.

'The suit is a spaceship?'

'Jem, this is Won.'

'One,' I repeat.

'Won,' he says again, drawing out the vowel.

'You really can't be here,' I tell her.

'I know. It's a difficult situation. It's not by choice,' she says. Her English is as good as Isley's.

'Can we fix your suit?' There have been incidents in other villages. Attacks. And there are villages we don't deal with, now, out of principle, like Simonscombe. Dominic made the case for breaking off communications with them, gave a speech at an open meeting when we heard about the burnings. He talked passionately of how we couldn't condone a return to barbarity.

They're not human, said Trevor, mildly, after raising his hand, and I get my feed from there. Dominic said, as if talking to a child: They're not human, but we are, aren't we? A few people clapped. It's a balancing act, a seesaw of beliefs kept in check only by fear of public disapproval, and I was concerned once I realised that; worried for Isley. But everything settled back down. This could shatter the peace.

'I don't think it can be fixed straight away. Not without getting a…' She stops speaking. There's a brief silence.

'Starter motor,' says Isley. 'That's the nearest way to describe it.'

'Qitan tech? How are you going to get that?'

'I don't know,' says Won. She puts her hand to her forehead, swipes at her hairline. It's a very familiar gesture, speaking eloquently of weariness. 'If I can get a message out, perhaps.'

'Right. A message.' It makes no sense to me.

'But for now,' says Isley, 'You'll hide, yes? Down in the cellar. That's the safest place.'

'Did anyone see her land?' The use of the pronoun slips out of me. Neither of them seems bothered by it.

'No, it travels without light, without sound. Nobody has noticed anything before.'

'Before?' I ask, and then I realise this is not a freak event. This is an error in a regular occurrence, and—yes—they know each other well. They finish each other's sentences, even. There's a level of communication between them that I'm only just beginning to see.

'Could we discuss this tomorrow?' says Won. 'I'm very tired.'

'We'll show you the cellar. We can make it comfortable.' He looks expectantly at me.

'That's why you woke me? To fetch bedding?'

'I didn't want you getting a shock. Finding Won here. Not without explanation.'

'Seems to me you haven't explained anything,' I say, and I'm angry. I don't want to be, but it can't be kept down, and I won't sleep now; he's robbed me of that as well. She's not meant to be here. I'll lie in bed for the rest of the night thinking about it.

'Could we talk more about it tomorrow?' he says.

'We could.'

'Then we will.' There's that hint of humour to his voice. At least, that's how I think of it. Or possibly it's a liking for completeness. For having the last word. He always does have the last word. But at least this time he doesn't tell me to go to bed.

They get up from their chairs and leave the room together. He follows her. She doesn't know the way, but he follows her, which makes no sense to me, and didn't they leave the room in some sort of synchronicity? Their steps in time? It reminds me of what some of the peacekeepers used to say, once they'd had a few too many at the Friday night functions. They'd talk of the way that Qitans could move as one, sometimes, without speaking. Of their mass migrations from one settlement to another. They never put up a fight, but they could have slaughtered us, one would say, and the others would agree. Why just move over and let us take it?

No battle. No military. Not one voice raised—at least, not theirs. A society of perfect peace. And now the ships of Earth come and go, taking their resources, selling their wealth, when they could simply have moved with one mind, and overwhelmed us.

Us and them.

All it took was the arrival of one more Qitan and I've begun to separate this situation into sides. How human I am, no matter how hard I try. We residents of the Western Protectorate, setting up our boundaries, priding ourselves on not being barbaric compared to the tiny villages not a few miles away. Being human is the problem, the whole huge problem in a nutshell, and I turn it over all night in my mind, sitting in the chair closest to the fire, stoking it and feeding it because the only alternative is the cold.