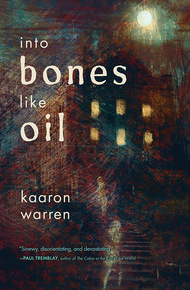

Kaaron Warren has been publishing ground-breaking fiction for over twenty years. Her novels and short stories have won over 20 awards, from local literary to international genre. She writes horror steeped in awful reality, with ghosts, hauntings, guilt, loss, love, crime, punishment and a lack of hope.

In this gothic-styled ghost story that simmers with strange, Warren shows once again her flair for exploring the mundane—themes of love, loss, grief, and guilt manifest in a way that is both hauntingly familiar and eerily askew.

People come to The Angelsea, a rooming house near the beach, for many reasons. Some come to get some sleep, because here, you sleep like the dead. Dora arrives seeking solitude and escape from reality. Instead, she finds a place haunted by the drowned and desperate, who speak through the sleeping inhabitants. She fears sleep herself, terrified that the ghosts of her daughters will tell her "it's all your fault we're dead." At the same time, she'd give anything to hear them one more time.

This is classic Kaaron Warren. A deeply haunting and atmospheric tale of a woman running from personal tragedy who checks in to a coastal boarding house rumored to help its residents find the sleep that illudes them. But they aren't the only inhabitants of the house: a nearby shipwreck has left a host of ghostly personalities who have their own stories to tell. – Tricia Reeks

"Into Bones Like Oil is an impressive, dark novella by one of Australia's most imaginative writers"

– The Canberra Times"This dark, ethereal novella by Warren . . . will especially appeal to horror readers who appreciate melancholic and atmospheric stories."

– Publishers Weekly"Dark, disturbing, visceral … it taps into a deep fear of not having our voice heard, our history recognised, our feelings taken into account and our motivations understood. Yet it is also a story which offers the chance of redemption, forgiveness, justice and, eventually, cathartic resolution."

– NB Magazine, Linda Hepworth (5 stars)The reception desk sat empty when Dora arrived at nine p.m. Good. That was the plan. The key to her room was in a lock box that wasn't locked ("It looks locked, that's the main thing," the landlord had told her). The key was there, along with a grease-stained sheet of rules and conditions (No Cooking In The Rooms ) and a hand-drawn map showing her where to find her bedroom.

She was on the ground floor, although it was really the lower ground level now since the building had sunk further into the ground over the years. She passed the doorway her map indicated opened into the breakfast room (7 a.m.–8 a.m. sharp). The room was dark except for the light of the hallway spilling in, but she could see six or seven tables already set up. Each table was laid for one person and she smiled; that was one less thing to worry about. The idea of having to eat with a stranger horrified her. She could barely stand eating with her own family. She thought she could smell bacon, but there was also mustiness and something else, like hot metal.

Someone had hand lettered a sign for the bathroom door—vacant—and that was a relief too, unless someone thought it was funny to turn the sign over when someone else was inside. She glanced up and down the hallway and, seeing no one, ducked into the bathroom, flipping the sign. The other side said: fuck off I'm in here.

The bathroom's floor and walls were tiled in pale purple streaked with gold. It gave the room an odd glow because the pale green glass-globed light fixture was set high in the ceiling and dimmed by dust and dead insects. The toilet was old but clean. There was no sign of spare toilet paper in the room. Against the wall was a shower and bath combination with a large, pale purple bathtub that sported rust stains and paint chips. The shower curtain was moldy and stained, but at least it existed. She hated showering without one.

She'd wash later, once she figured out who was around and where they were.

She listened at the bathroom door and, hearing nothing, stepped into the hallway. She flipped the sign back to vacant. There were three doors off this stretch, one marked linen, with a lock, the others numbered. It was very quiet, but from each room came a slow murmur, a hum like a one-sided conversation.

She heard the gentle ticking of a large clock but couldn't see one.

The map said her room lay at the end of the hall. The key was small and flimsy, and she hoped it would work. She was relieved when it turned smoothly as it must have done a thousand times before.

Dora slid the door open. It was lightweight, shaking in the track as it moved. It would provide very little security. But then she was in an inner-city rooming house, so her expectation of security was low.

Her room had once been the foyer, when the house was much smaller and the entrance faced the other way. Now, after renovations and changes, it faced an alleyway. The old front door, now most of one of the walls, was covered with clothes hooks of many kinds. Her wardrobe. She thought previous tenants must have hammered the hooks in as there was nowhere else to hang clothes. There was no chest of drawers in the room, only one shelf over the bed, set into the wall. It looked like the place where, decades ago when a family lived here and milk was delivered to the door, the milkman would have put the bottles. She didn't remember those days, but her grandmother did, once wistfully and now as if it were still the case, as if milk was delivered each morning. There were six or seven books on the shelf.

Dora had very little with her. One small suitcase that she'd used as a seat and a pillow over the last week. There was no room to lay her suitcase out on the floor so she hefted it onto the bed. Opening the zip, she threw back the lid. She hung T-shirts and skirts and pants, two of each, on the hooks, folded her underwear onto the shelf. She had one book (Chicken Soup for the Grieving Soul) but no photos. She zipped the suitcase closed, lifted it off the bed, and placed it upright on the floor. Once she covered it with a pillowcase or a towel it would be a fine bedside table.

She moved the seven books, all by R.L. Stephenson (Confessions of the Dead, Parts I–V, Lore of the Sea, and The Wreck) from the shelf and placed them beside her suitcase. There was a blue bottle she left on the shelf, and—beside it—she placed two children's hairbrushes, pink and run through with strands of hair.

It was dead quiet outside. She hadn't eaten since lunch but was loath to go out. She wished she could leave by the old front door, but it was nailed shut. At least she had a window, a bay window looking onto the alleyway. Thick lace curtains covered it, and successive tenants had layered paper over the window for privacy, but someone had scratched a small square at the top to let light in.

She placed her book on the suitcase-table. She had half a cheese sandwich she'd saved from lunch so she ate that, then turned the light out and changed. The single bed creaked as she climbed into it, and the sheets felt slightly clammy. The rooming house shifted and she could hear footsteps, voices, cars outside. She could hear the ticking of the old clock. She heard something heavy being dragged, and a creaking noise where the door used to be, as if that door was being opened.

She sat up. The door was only a reach away, and she could see by the streetlight leaking through the layers on the window and streaming through the bare patch. She could feel when she touched it that the door was nailed shut.

She lay back down, hoping for sleep.

It had been many months since she'd slept well. Even before the children disappeared and were found, her worries had weighed her down, kept her awake and thinking when all she wanted was blessed sleep.

Even when her mother looked after the children and she was on her own, still she couldn't sleep. Back then, she'd convinced herself her ex-husband was a monster, and she sat curled up in an armchair (one they'd paid a fortune for, which she'd never regretted) swamped by the large blanket crocheted by her grandmother, holding her phone, waiting for the call to confirm he'd taken them, that her children were kidnapped by their own father, the man who'd loved her once.

The call never came. The children were always fine at her mother's.

Dora pulled the blanket up under her chin. It felt clammy and smelled faintly of wet hair and bleach.

A gentle noise streamed from a corner of the room: the rhythmic wash of the sea rolling into shore and back. The sound came from a speaker in the ceiling. She'd heard about this, the white or pink noise that would supposedly help her sleep. Over that, she could hear the upstairs neighbor moving around. It sounded like they were dragging furniture and bouncing a ball and throwing glasses onto the floor—all at the same time.

She was tired. Very, very tired at her core. The body shuts down, sleeps when sick or starving or dying. You only had to look at footage of starving children to see that.