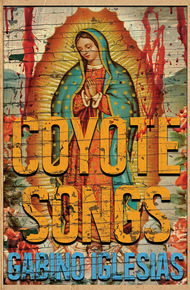

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, journalist, professor, and literary critic living in Austin, TX. He is the author of ZERO SAINTS and COYOTE SONGS and the editor of BOTH SIDES and HALLDARK HOLIDAYS. His work has been nominated twice to the Bram Stoker Award as well as the Locus Award and won the Wonderland Book Award for Best Novel in 2019. His nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Electric Literature, and LitReactor. His reviews appear regularly in places like NPR, Publishers Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, Criminal Element, Mystery Tribune, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and other venues. He's been a juror for the Shirley Jackson Awards twice and has judged the PANK Big Book Contest, the Splatterpunk Awards, the Newfound Prose Prize, and the 2021 FIU Student Literary Awards, among others. He has offered keynotes at various institutions and events, including the Lighthouse Book Project, ARRTCon, the inaugural POP_UP Academic Conference on Popular Culture, and the Revolve Creative Conference. In 2021, he received the Horror Writer's Association Diversity Grant. Iglesias has worked as a mentor with the San Francisco Creative Writing Institute and the Periplus Collective. He is a member of the Horror Writers Association, the Mystery Writers of America, and the National Book Critics Circle. He teaches creative writing at Southern New Hampshire University's online MFA program. You can find him on Twitter at @Gabino_Iglesias.

In Gabino Iglesias' second novel, ghosts and old gods guide the hands of those caught up in a violent struggle to save the soul of the American southwest.

A man tasked with shuttling children over the border believes the Virgin Mary is guiding him towards final justice. A woman offers colonizer blood to the Mother of Chaos. A boy joins corpse destroyers to seek vengeance for the death of his father.These stories intertwine with those of a vengeful spirit and a hungry creature to paint a timely, compelling, pulpy portrait of revenge, family, and hope.

Gabino's novel is a superbly written, gritty tale of heartbreak, violence and revenge that interweaves the lives of a cast of characters living on the US/Mexican border with those of vengeful spirits, gods, and the supernatural. This book was my introduction to Gabino's writing and it stuck with me for a long time. – Tricia Reeks

"Sometimes the drums beating in my blood get too loud. They take over and silence all the other nonsense, all the other things trying to distract me with their immediacy, their apparent ties to the apocalypse, their loud, obnoxious wrongness. When that happens, I close my eyes and listen to my blood, and when I do that, this is what I hear:

I hear the drums, the stretched skins of dead animals, thrumming powerfully, undeniably through my veins, carrying with them the songs of lost people, mixed cultures, and a plethora of angry gods hidden inside the new gods the Spaniards imposed on two thirds of my DNA.

I hear the strength of my great-great-great-grand- mother, who escaped slavery across a deadly river that poet Julia de Burgos later loved with her cuerpo y alma. I hear her voice in my blood say that no person should ever be owned and that laughing in the face of death is better than having to live as abused property.

I hear the labor and the love and the blood and the patience of generations of women who fought for better days and more opportunities and less hunger and more justice. I hear the soft rasping sound made by the calloused hands of men who battled to put food on the table and did all they could to make sure their kids grew up knowing the difference between right and wrong. I hear them all saying I need to remember everything, especially because I am the migrant daughter of a migrant, the daughter of a mother whose DNA carries the knowledge of escape and the fear and hatred that comes from abused flesh, from the whistling of the whip in the air.

I hear the world spinning as poems are written and babies are born and bullets fly and music is made and jobs are lost and spells are cast and cars crash and alcohol disappears down gullets and leaves fall to the ground and alley cats sing to the night with voices they borrow from depressed demons and hatred tries to win the battle and inspiration vanishes and a kid becomes a walking miracle as she crosses the border without being raped or abused or denigrated and an angry lover puts his vengeance inside a sharp blade and water flows full of memories from its eternal recycling and some nameless bird bathes in it before a homeless man drops a cigarette butt that will end up in the creek, mixed in with all that eternal return.

I hear the obscene screams of angry gods who were forced to dress their black skin in whiteness to survive once their devotees were brought to the Caribbean. Their strength is there, coursing through the streets like the blood courses through my veins, because we still call their names, pray to them, light candles, offer them tiny deaths and food and fire and dreams.

I hear a whole house shaking and groaning as a train to who knows where rattles by on the too-close tracks as my grandmother pets an unnamed cat and adjusts her glasses on her almost useless eyes with hands covered in a mixture of lines and scars that heal you with their touch. I hear her spirit hovering above me, raining love down on my head, reminding me that wounds become scars that become stories that become herstory. Reminding me that nothing is free. Reminding me that my skin is a miracle and my soul its own deity and my future a malleable thing I can shape with sweat and blood and tears and effort.

I hear my other grandmother saying that the bathroom in the hallway belongs to the spirits, a los muertos, and the saints. Never blow out those candles, she says. Never forget your prayers, mijita, she reminds me. Never put your own purse or let the other women in your life put their purses on the ground. Never take a pregnant woman to a funeral, mija. Never leave your milagritos at home, she repeats, pulling her dress to the side to reveal a hundred tiny pieces of metal pulling at her bra. I hear her laugh and I hear her telling me to let dogs lick my wounds because that worked for San Lázaro and thus it will work for me. She tells me this as the huge statue of San Lázaro looks on, black, tall, skinny, and surrounded by a pack of skinny dogs I'll never forget.

I hear the aching eloquence of my father's silence as he drinks in the kitchen, cloaked in darkness, a million miles from home, probably regretting passing on to me the invisible gene that makes us nomads, hardheaded hustlers, beautiful, flawed creatures that are too quick to love and too quick to anger.

I hear my mother crying after calling the cops on me for fighting a girl in our barrio and threatening her with a knife and then laughing after lying to the cops for me and crying because my sister is doing things that never lead to good things and so am I and, carajo, she tried with all she had but sometimes all you have is not nearly enough.

I hear an endless succession of planes taking off and landing and more or less creating the fabric of life with their constant motion, their incessant pregnancy with all of us, their hunger for goodbyes and tears and promises.

I hear an old lady saying "Que Dios te bendiga, mija" while another says "Tranquila, niña, que Elegguá abre el camino." And then comes the holy music. Rubén Blades. Héctor Lavoe. Roberto Roena. Celia Cruz. Frankie Ruíz. Eddie Palmieri. Y después el gran Maelo, reminding me I'm still alive.

I hear the streets of Rio Piedras dancing to their own hot rhythm, the cobblestones of Viejo San Juan cracking under the weight of history and oppression, the cries of a pueblo that grew up as a colony and stayed there like a use- less daughter who lacks the strength to move out, to learn that some things are better left in the past. I hear Yukiyú screaming and floods and crying and parties and dominoes clacking together and violence and beauty and hurricanes and that thing in my chest that calls me home every day.

I hear waves and sweat and drunk afternoons and meat sizzling on a grill and someone vomiting out their pain and someone praying as they yank the head off a chicken and my grandma asking for blessings for the dead as we drive past a cemetery and a chord on a guitar with one finger in the wrong place and brakes screaming in the distance and the laughter of my friends at home, their skins and hair and eyes of every color imaginable and then the song of the coquí signaling another trip around the sun and finally guns going off in the Luis Lloréns Torres projects as I drift off to sleep. I hear someone explain that the things you love can haunt you, and vice versa.

I hear "Where are you originally from?" and "Where is your accent from?" and "Wow, you're so eloquent!" and "You're very pretty...for a dark girl" and "Are you Mex- ican?" and "Are you from Jamaica?" and "Is one of your parents white?" and "Nice hair! Can I touch it?" and a mil- lion other dumb comments that scholars say I should call microagressions but that sometimes feel anything but micro.

I hear my own anger claiming that I am a daughter of Changó while the sound of a bagpipe reaches into my DNA and threatens to put tears in my eyes and I want to stuff the whole world inside my heart and keep it there, next to that feeling I get when I read Langston Hughes or when the creek outside my window tells me to be like it, to carry on regardless of what others are doing and to teach them to fear my wrath.

I hear the cultures that came together to make my blood scream at the fact that no one wanted things to turn out the way they did. I hear them loud and clear in the faces that inhabit my memory, in the voices I carry in my heart, in the color of my skin and the irresistible pull of some spaces, some songs, some poems, some chunks of sand seldom visited by people.

I hear all this and more, and then I open my eyes and read about others wanting "pure blood," wanting to keep their racial purity, their god a blue-eyed hipster, their bastardized language intact. That makes me laugh with closed fists. You don't know the beauty of flavor, pendejo. You keep your dumb ideas of purity and I'll revel in the music of my mixed blood, my mutt blood, my earthly blood, my multitudinous blood, my brown and Rican and black and European and white and African blood, my eternal, magic, ancient blood.

Yeah, when nothing makes sense, I close my eyes and listen to my blood."