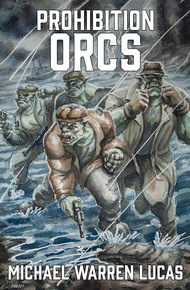

Michael Warren Lucas has published over fifty books, despite society's best efforts to stop him. His other titles include Apocalypse Moi, the Prohibition Orcs historical fantasies, and the 80s SF satire Laserblasted.

ELVES WENT INTO THE WEST—TO AMERICA.

GENERATIONS LATER, ORCS FOLLOWED.

1927 Detroit. Orcs fight Prohibition, avoid police, and labor hard for their children. All while doing their best to navigate the narrow human world. Men drive fancy Dodges and Cadillacs; orcs squeeze into fourth-hand Model Ts. Dwarves dominate the skilled trades; orcs push brooms. And behind everything, elves make it their life's work to deny orcs have worth.

To be an orc is to endure, but when the world tries to deny even that, an orc must act.

And Uruk-Tai will do anything for his family.

This long-demanded collection includes all the Prohibition Orcs tales—Spilled Mirovar, Final Gift, Drowned Mirovar, Witness November, Degreased Hopes, Woolen Torment, and the previously unpublished A Debt of Meat.

Try a thought experiment: Pretend that the Victorian era continued and Prohibition still happened. Now imagine Detroit. That's where you find a group of Orcs, just trying to get along. I've loved the Prohibition Orcs from the moment I first saw them, and they could only come from the imagination of Michigan writer (and tech wiz), Michael Lucas. – Kristine Kathryn Rusch

"I love these stories"

– Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Hugo- and Nebula-award winning author of The Fey"The fun you need, the spite you crave. Lucas's orc tales are the most humane fantasies I've read in a long time. They leave me wanting more from that world, not because there's anything lacking, but because they're so fully-realized. And fun."

– ZZ Claybourne, author of Afro Puffs are the Antennae of the Universe"As methodically, absorbingly constructed by Lucas, each story is a poignant step forward for an individual orc… and, by extension, all orcs inhabiting America."

– Robert Jeschonek, author of My Favorite Band Does Not Exist1

Uruk knelt on one knee on the verge of the rock-strewn gravel beach, letting his thick wool coat almost brush the ground and give his legs a little more protection from the sleet screaming down from Grosse Pointe's furious night sky. He had yanked his collar up and jammed his corduroy flat cap tightly over his scalp, and crammed his strong hands into the coat's pockets.

One hand bore brutal brass knuckles. He'd chosen the braided knuckles, the ones without the spikes. The other hand cradled the wooden grip of an orc-scale revolver, slightly too large for humans and chambered for .75-caliber bullets. Spare bullets rattled in the bottom of the pocket.

Like any American orc, he kept his talons trimmed so that they wouldn't tear out his pockets. Or the rest of his clothes.

Or other soft things. Like bricks.

If events continued as they had, though, he might have to let them grow.

The modern year of 1927, and orcs still had to fight elven asshole bullshit.

Lake Saint Clair wasn't really a Great Lake but tonight it raged like one, thrashing up waves that clawed their way fifteen or twenty feet inland before they collapsed, sometimes even sluicing over the macadam of Lakeshore Drive. Each wave discarded a fresh skein of noxious seaweed, dead from the November cold, and the greatest surges sprayed the stink of dying algae across his face.

Uruk wondered if the lake felt like an orc. Lake Huron, Lake Superior, they all got the glory. They were strong and angry lakes, yes. They demanded sacrifice of blood and bone, on their own calendar. But even little Lake Saint Clair, when roused, devoured those who disrespected it.

An orc with any sense would be at home. Even his family's seething, roach-ruled tenement apartment in Hamtramck would be nicer than this freezing, angry midnight. Grandpa always said anger keeps you warm enough, but the icewater punching the gap between cap and collar and shivering down his spine disagreed. Still, his heavy boots with the layered leather soles repulsed rain and cold alike, and beneath the pleated wool coat his thick black sweater and brown canvas pants kept his vitals warm enough.

Fury did not keep you warm.

It just kept you where you needed to be.

Elves could see in the dark—but not on a night like tonight. Even orcs couldn't see in the dark when the screaming wind and sleet stole the heat from the air. The sprawling mansions facing the lake across Lakeshore Drive were merely darker shadows buried in trees.

A wave crashed up towards Uruk. Behind him, Daka cursed in Orcish. His brother had planted himself too close to the water, again. He probably had wet feet. Again. Daka always put himself too close to the edge, any edge. Uruk had tried to ease him back for years, but finally resigned himself to the fact his brother liked wet feet and dented fenders and angry landlords.

But for something like this, Daka was on the side of right. As were Tara and Kaba.

Uruk had tried to fit into America. He'd listened to all his father's stories about the Old Country and what it meant to be a real orc. Uruk saw a difference in the United States, though. He'd gone to school for two whole years, and could sign his name and count and knew the sagas of General Presidents Washington and Lincoln. He'd learned English, though he spoke Orc at home. He let the humans and dwarves call him Urka—their feeble misshapen mouths and flimsy voices could never properly pronounce his good, traditional Orcish name.

Uruk might show a fang at a bar, but had never killed anyone. He'd never even broken a jaw, no matter what some ignorant human or dwarf said.

Even Uruk's aging father had learned the comforts of the overstuffed chair. Now that he'd become Grandpa, he spent his days grumping at how things had changed and how much more Orcish the Old Country had been. He watched the children with not-so-secret pride, though.

Detroit was a wonderful place.

But some things went too far. Like the Eighteenth Amendment. Humans could ban their own booze all they wanted. It was feeble, not even fit for washing floors. They'd left exceptions for their church, for the elvish sacraments, even for the dwarven rituals.

But the elves in Congress insisted that orcs had no sacraments. Elves had supported that Prohibition, and immediately started smuggling their mirovar from Canadian distilleries. As the orcs had done with their draught, until last month's disaster.

Without the Orcish draught, without the rites, Uruk's fine strong boys might grow tall. They might earn respect. They might have many fine children of their own and, in time, name Uruk Grandpa.

But they would never be orcs.

There—a sudden flash of light, right on the point!

And again!

Elves.

Guiding their pet bootleggers in.

Uruk raised his left hand in a fist, just like Grandpa talked about, and rose to his feet. "For our children," he snarled in Orcish.

Even with sleet pelting his cap, Uruk heard the gravel behind him shift as his brothers rose with him. "Our children."

An orc who wanted respect had to take it by force.

2

The quick dash down a quarter-mile of grassy, squelchy verge between the broken rocks of the beach and the muddy mess of Jefferson Avenue felt like nothing, even in the cold darkness and the pummeling sleet. Uruk's heart beat steadily and his breath came easily. He worked as a laborer down at the Port of Detroit with Daka and Kaba. Hauling boxes and toting bales that would cripple a human or crush an elf had only strengthened him.

Tara lagged a little behind. The youngest brother had gotten himself apprenticed to a janitor—honorable work, yes, but not labor that would make him strong. Uruk didn't question his brother's heart, though. Tara's weakness might kill him. But if needed, he would fall with elf blood under his trimmed talons and an elven throat in his teeth.

Uruk had passed this place before, driving the clan's rusty decrepit Model T. During the summer, the narrow spit of land stabbing into Lake Saint Clair was a pleasant, grassy picnic spot for elves and humans and even a few dwarves. A dozen families with basket lunches could comfortably sprawl on that peninsula, leaving room for their children to run and play, surrounded on three sides by water and watching the sailboats and freighters and the distant Canada shore. Maybe even flying kites.

There was no law against orcs stopping at that little park.

Laws are written down.

Tonight, though, Lake Saint Clair battered the peninsula, clawing at the tumbled boulders along its edge, spitting and spraying like a rabid wolf. Lightning shattered the sky, and thunder demanded obeisance.

The flash of light exposed a fifteen-foot boat wedged up on the peninsula, through a narrow gap in the rocks. Rowboat? No, in a storm of this madness it had to be a powerboat. Crewed by madmen, or elves. A four-wheeled delivery truck with a giant tomato painted on the side sat facing the road.

The tomato convinced Uruk this was the rendezvous.

Anyone could have a new truck. The lightning had reflected off the great swooping fenders in even curves, unmarred by dents and bumps and all the other damage of Detroit's busy traffic. Maybe they'd just bought the truck today.

But the sole tomato on the side wasn't the work of a sign painter. Nobody had dropped a sawbuck in an artist's hand and said "Gimme a great big tomato." No, even in the quick flash of monochrome lightning, this tomato advertised richness and flavor. The artist had poured the very essence of tomato into the paint, and brought the perfect ripe tomato to life on taut waterproof canvas.

The tomato was elf art. And elves painted only for elves and Presidents.

The informant had been right. The transfer was tonight.

Right now.

Between the truck and the road, two men.

Uruk held his hands out to warn his brothers, and stopped behind an ancient oak tree. His heart suddenly beat more quickly, and a ripple of tension flowed up his spine and tensed his shoulders. Grandpa talked about preparing for battle any time you were willing to listen.

Grandpa hadn't mentioned the sudden spike of fear through the gut, though.

Turning to face his younger brothers, sleet spattered Uruk's face and the sharp wind burned tears from his eyes. Daka, in his fedora and long coat of rough brown leather, looked almost relaxed. As Tara panted for breath and hugged his thinner wool coat his mouth hung open a little, exposing his two Great Tusks but not the Lesser. Surprisingly Kaba, the strongest of them all, looked the most nervous. His leather-gloved hands were clutched into almost human fists.

Uruk had planned to take Tara, the weakest of them. But Kaba's eyes flickered nervously between the lake and the road. There is more than one kind of weakness, Grandpa said. While Tara's weakness might kill him, Kaba's might murder them all. "Kaba, with me. We take the one on the left. Tara, Daka, the right." Uruk raised the hand with the brass knuckles. "Do not kill unless we must."

Little Tara nodded and slipped on his own pair of knuckles. These had inch-long steel spikes above each hole.

You'll need every advantage, littlest brother.

Uruk put a heavy hand on Kaba's bicep. "We have not done this before," he hissed in English. "But we are orcs. It's in our blood. We can do this."

A stream of water spilled off of Kaba's flat cap. Then his chest heaved with a deep breath and he gave a quick nod.

"Good orc." Uruk looked at his brothers. "Go!"

They charged.

Uruk could barely see Kaba thundering beside him. Grandpa was right—an orc's matte purple-green skin was made for the night. If he couldn't see his other two brothers from ten feet away, the guards would have no chance.

The guard stood with his back to the thrashing lake, silhouetted against the crazy reflections of the incoherent water. Almost big enough to be an orc, the outline of his fedora showed him swinging his head one way, then the other, looking for lights or motion. Not complacent, but not alert enough. Uruk gave heartfelt thanks to the lake for the spray and the splash and the pounding waves that covered his thudding feet.

The guard had a short-barreled Tommy gun with a big round magazine slung over one shoulder, barrel pointed down to keep the rain out. The weapon could down an orc in two seconds, and the sight sent fear fluttering through the bottom of Uruk's guts, but he used it to charge faster and harder.

They were maybe ten feet away when the guard caught the motion in the darkness. His head snapped towards them, and his hands fumbled at the submachine gun.

A high-pitched human scream pierced the spray and crash.

The guard wrenched at the Tommy gun, spinning towards the darkness that hid his partner. He might have opened his mouth to shout.

Uruk hit him like a freight train striking a dog, sheer momentum throwing the brawny human to the ground. A second later he heard an oof of exploding air, and glanced over his shoulder to see Kaba pulling the Tommy gun off the guard's shoulder. The guard lay still on the ground.

Kaba saw Uruk's expression, and pantomimed a punch to the guard's gut.

Shouts rose from behind the truck.

Uruk charged again.

Four humans stood behind the truck, each lugging a wooden milk crate from the boat to the back of the truck. A couple of bigger humans, the sort the elves passed off as muscle, loomed near the boat.

And near the truck, in an immaculate yellow rubberized rain slicker, an elf.

Uruk had hoped he'd finally get to see an elf look surprised. Instead, the elf gracefully pirouetted out of the path of Uruk's charge, raising his hands as if waving a red cape for a bull.

The workmen didn't matter. Not now. The elf was the threat.

Uruk scrabbled to reverse course, but the leather soles of his boots wouldn't grab the slick grass. He barreled into one of the workmen, feet-first, sending the human tumbling aside.

The crate spun through the air.

Glass bottles shone in a barrage of lightning, then the crash of glass breaking against stone introduced the thunder. The smells of honey and roses and tulips and a dozen other flowers pierced the air.

Uruk had never smelled mirovar, the sacramental—no, sacred—drink of the elves. It smelled just as stuck-up as he'd thought.

The elf shrieked, "Unspeakable cretin!" He raised a finger at Uruk.

Lightning crackled again, this time from the elf's outstretched finger.

Sudden pain lashed up Uruk's legs, scorching through his chest and out towards the sky. Uruk smelled burning wool and hair and something like scorched bacon.

The blast left him hollow.

The spray and storm flooded in to fill the space with darkness.