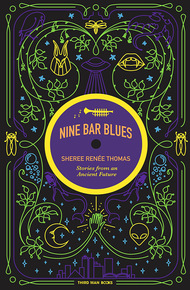

Sheree Renée Thomas is an award-winning fiction writer, poet, and editor. Her work is inspired by myth and folklore, natural science, and the genius of the Mississippi Delta. She is the author of Nine Bar Blues: Stories from an Ancient Future (Third Man Books), and the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and associate editor of Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora.

The stories collected in Nine Bar Blues weave emotion, spirit, and music, captivating readers with newfound alchemy and the murmurs of dark gods. Rooted in rhythm, threaded with magic, these tales encompass worlds that begin in river bottoms, pass through spectral gates, and end in distant uncharted worlds. These stories describe the pain that often accompanies the confines of sanctuary and the joy that is inextricably bound to the troubles of hard living. Nine Bar Blues sings a multiverse of fully realized worlds that readers will remember for ages to come and cherish from page to heart thumping, foot-stomping page.

Sheree Renée Thomas, two-time World Fantasy Award-Winner and editor of the seminal Dark Matter anthologies and Africa Risen, is a titan in the industry. Her debut short story collection, Nine Bar Blues, weaves Southern musical traditions with Afrofuturist musings, sure to deliver an unforgettable experience. – Zelda Knight

"Sheree Renée Thomas gives us a whirlpool of poem and story, a 'wild and strangeful breed' of cosmology … "

– Tyehimba Jess, Pulitzer Prize Winner, author of Olio and LeadbellyANCESTRIES

In the beginning were the ancestors, gods of earth who breathed the air and walked in flesh. Their backs were straight and their temples tall. We carved the ancestors from the scented wood, before the fire and the poison water took them, too. We rubbed ebony-stained oil on their braided hair and placed them on the altars with the first harvest, the nuts and the fresh fruit. None would eat before the ancestors were fed, for it was through their blood and toil we emerged from the dark sea to be.

But that was then, and this is now, and we are another tale.

It begins as all stories must, with an ending. My story begins when my world ended, the day my sister shoved me into the ancestors' altar. That morning, one sun before Oma Day, my bare heels slipped in bright gold and orange paste. Sorcadia blossoms lay flattened, their juicy red centers already drying on the ground. The air in my lungs disappeared. Struggling to breathe, I pressed my palm over the spoiled flowers, as if I could hide the damage. Before Yera could cover her smile, the younger children came.

"Fele, Fele," they cried and backed away, "the ancient ones will claim you!" Their voices were filled with derision but their eyes held something else, something close to fear.

"Claim her?" Yera threw her head back, the fishtail braid snaking down the hollow of her back, a dark slick eel. "She is not worthy," she said to the children, and turned her eyes on them. They scattered like chickens. Shrill laughter made the sorcadia plants dance. A dark witness, the fat purple vines and shoots twisted and undulated above me. I bowed my head. Even the plants took part in my shame.

"And I don't need you, shadow," Yera said, turning to me, her face a brighter, crooked reflection of my own. "You are just a spare." A spare.

Only a few breaths older than me, Yera, my twin, has hated me since before birth.

Our oma says even in the womb, my sister fought me, that our mother's labors were so long because Yera held me fast, her tiny fingers clasped around my throat, as if to stop the breath I had yet to take. The origin of her disdain is a mystery, a blessing unrevealed. All I know is that when I was born, Yera gave me a kick before she was pushed out of our mother's womb, a kick so strong it left an impression, a mark, like a bright shining star in the middle of my chest.

This star, the symbol of my mother's love and my sister's hate, is another way my story ended.

I am told that I refused to follow, that I lay inside my mother, after her waters spilled, after my sister abandoned me, gasping like a small fish, gasping for breath. That in her delirium my mother sang to me, calling, begging me to make the journey on, that she made promises to the old gods, to the ancestors who once walked our land, to those of the deep, promises that a mother should never make.

"You were the bebe one, head so shiny, slick like a ripe green seed," our oma would say.

"Ripe," Yera echoed, her voice sweet for Oma, sweet as the sorcadia tree's fruit, but her mouth was crooked, slanting at me. Yera had as many faces as the ancestors that once walked our land, but none she hated more than mine.

While I slept, Yera took the spines our oma collected from the popper fish and sharpened them, pushed the spines deep into the star in my chest. I'd wake to scream, but the paralysis would take hold, and I would lie in my pallet, seeing, knowing, feeling but unable to fight or defend.

When we were lardah, and I had done something to displease her—rise awake, breathe, talk, stand—Yera would dig her nails into my right shoulder and hiss in my ear. "Shadow, spare. Thief of life. You are the reason we have no mother." It was my sister's favorite way to steal my joy.

And then, when she saw my face cloud, as the sky before rain, she would take me into her arms and stroke me. "There, my sister, my second, my own broken one," she would coo. "When I descend, you can have mother's comb, and put it in your own hair. Remember me," she would whisper in my ear, her breath soft and warm as any lover. "Remember me," and then she would stick her tongue inside my ear and pinch me until I screamed.

Our oma tried to protect me, but her loyalty was like the suwa wind, inconstant, mercurial. Oma only saw what she wanted. Older age and even older love made her forget the rest.

"Come!" I could hear the drumbeat echo of her clapping hands. "Yera, Fele," she sang, her tongue adding more syllables to our names, Yera, Fele, the words for one and two. The high pitch meant it was time to braid Oma's hair. The multiversal loops meant she wanted the complex spiral pattern. Three hours of labor, if my hands did not cramp first, maybe less if Yera was feeling industrious.

With our oma calling us back home, I wiped my palms on the inside of my thighs, and ignored the stares. My sister did not reach back to help me. A crowd had gathered, pointing but silent. No words were needed here. The lines in their faces said it all. I trudged behind Yera's tall, straight back, my eyes focused on the fishtail's tip.

"They should have buried you with the afterbirth."