Stephanie Rabig has been a fan of horror since she was old enough to sneak Stephen King books off her father's bookshelf. Her favorite horror subgenres include cryptozoology, isolation (John Carpenter's The Thing is a perfect example), and western. When she's not reading or writing, she's making resin art, wrangling her two children, or filming the antics of her (many, many) cats.

When a prairie-mad settler murders Milton Allen's brother and his family, the wealthy rancher offers an enormous bounty to bring the culprit in. Ada Marshall and Pearl Beckwourth, bounty hunters with twenty years experience, assume this is yet another straightforward job. But when a fellow bounty hunter is torn to pieces not fifty feet away from their camp, their natural wariness grows, and in the tiny, isolated valley town of Woodlawn, they learn that the attacker may not even be human...

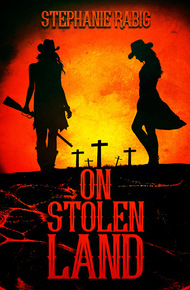

Stephanie Rabig's On Stolen Land is a vital and eye-opening work that offers an insightful perspective on the ongoing struggles of Indigenous peoples. Through powerful storytelling and well-researched analysis, Rabig delves into the history of colonization and its ongoing impact on Indigenous communities. This book is a must-read for anyone interested in social justice and understanding the complexity of land rights issues. – Tammy Salyer

"Gritty and bleak, On Stolen Land makes for a harrowing read, one filled with moments that'll remain with you long after you've read it."

– Steve Stred, Splatterpunk-nominated author of Sacrament"If you like your Westerns more James Wan than John Ford, you'll enjoy this."

– Janine Pipe, author of SAUSAGES: The Making of Dog Soldiers"Fun, fast paced, with glorious character building and a compelling storyline. A stellar sample of the splatter Western genre."

– Laurel Hightower, author of BelowAda Marshall sat in the dust outside of an elaborately-painted tipi, waiting for her wife's brother to die.

She and Jim hadn't always seen eye-to-eye: some of his remarks to Pearl over the years had seemed less the teasing of an older sibling and more his sincere belief that he was better than she was. But even her own considerable temper had been swayed to compassion by the hardships he'd suffered these past few years.

At least he was dying as much on his own terms as any man was likely to get. He hadn't been struck down by a bullet or an arrow, as both she and Pearl (and, to be honest, Jim) had long expected. He was surrounded by his family, both blood and adopted.

She could hear low voices inside, and despite herself strained to hear what they might be saying. Then one of the Crow women walked by, and though she didn't so much as give her a reproving glance, Ada still scooted away from the flap, ashamed of her snooping.

Inside the tipi, Pearl held her brother's hand, staring into a dear face that she'd never grown to know as well as she'd like. There were the powder burns in his left cheek that remained from when he'd grabbed the barrel of a gun that had been aimed at him; the bags under his eyes, while a more recent development, still seemed like they'd somehow always been there, even as a boy. Her brother, carrying a weight beyond his years since the day he'd been a child and discovered his playmates massacred in front of their home.

He'd been closer to those children than he had been to his own brothers and sisters, a habit that had continued throughout his life. Their father choosing to emancipate Jim and not any of the rest of them ("Freedom is a difficult thing," her father had said, in a tone he'd thought was kind. "You're safer here with me.") had created an inescapable rift, one that she'd never been able to mend to her satisfaction.

Two of her siblings had eventually escaped alongside her―Charley, who had followed Jim's footsteps as a mountain man, and Della, who had settled with her husband Alonzo in New York. She had been able to write Della, at least, tell her of her upcoming visit to Jim, but though she'd checked for a return letter at the nearest post office several times, none had come in. She doubted Charley would have come, either, even if she had known how to contact him. Jim, as Della had told her on their visit to New York years ago, was little more than a stranger―a famous stranger other people spoke of fondly and his own kin barely knew.

His mustache was stained with blood from a nosebleed that barely gave him a moment's peace. She reached out with her handkerchief to dab it clean again, but then he murmured something.

"What?" she asked.

Though he repeated it, the word made no more sense to her, and she realized then that he wasn't speaking English.

"My wife," he whispered.

She smiled. "Which one, Jim?"

He smiled back, which heartened her, if only for a few seconds. His skin felt like old paper, and the look in his eyes, even more than the frailty of his body, let her know that he wouldn't be here come nightfall.

"Blackfoot. As-as-to's daughter. I...I hurt her bad, Pearl."

"I know." He had told her about the incident one drunken night, about how he'd become infuriated at his new wife taking part in a scalp dance he'd told her to sit out, being that some of those men had been his allies. When she'd ignored his orders, he'd struck her a blow that had nearly killed her.

At the time, Jim had told it as a younger man still certain in his convictions. She, equally certain in hers, hadn't spoken to him for years. They had finally reunited only after his unwilling role in an event that eclipsed all of their arguments, both petty and serious, in the scope of its horror.

"Shouldn't have done that. Shouldn't have done a lot of things."

"Thought you told me you were going to the grave content."

"Thought I was."

"Well, I'll miss you. And I don't like many people enough to miss them, so you can take solace in that," she said, giving him the teasing smile they'd shared for such a short time as children, before their father had emancipated him and he'd been off first on blacksmithing work and then on trapping expeditions deep in the mountains.

She would miss him, was the damnable thing. But she'd spent most of her life missing him, so at least it'd come natural.