Aliya Whiteley's strange novels and novellas explore genre, and have been shortlisted for multiple awards including the Arthur C. Clarke Award, BFS and BSFA awards, and a Shirley Jackson Award. Her short fiction has appeared in many places including Beneath Ceaseless Skies, F&SF, Strange Horizons, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, Lonely Planet and The Guardian. She also writes a regular non-fiction column for Interzone magazine. She lives in West Sussex, UK.

Aliya Whiteley has been recognised by many awards committees, including two shortlistings for the Arthur C. Clarke Award – 2022 for Skyward Inn and 2019 for The Loosening Skin

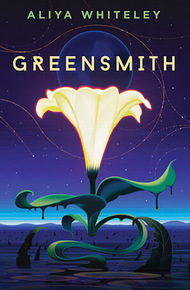

Penelope Greensmith is a bio-librarian, responsible for a vast seed bank made possible by the mysterious Vice she inherited from her father.

She lives a small, dedicated life until the day the enigmatic and charming Horticulturalist arrives in her garden, asking to see her collection. He thinks it could hold the key to stopping a terrible plague sweeping the universe.

Soon Penelope is whisked away on an intergalactic adventure by the Horticulturalist, experiencing the vast and bizarre mysteries that lie among the stars.

But as this gentle woman searches for a way to save the universe, her daughter Lily is still on Earth, trying to track her down, and struggling to survive the terrible events unfolding there…

I've been a fan of Aliya's for years, and even got to blurb her very early – and excellent! – collection Witchcraft in the Harem back in the day. Since then she's gathered award nominations left right and centre (or center, for US readers!), and quietly produced some of the best British SF/F works of recent time, of which Greensmith is a fabulous example. – Lavie Tidhar

"A brilliant mind altering, intergalactic delight. Brimming with humour and flair. Greensmith marks Aliya Whiteley's distinctive talents as something to get excited about."

– Irenosen Okojie, award-winning author of Nudibranch, Butterfly Fish and Speak Gigantular"One of the most poignant, elegiac and spiritual works of science fiction I have read all year."

– Nina Allan, award-winning writer of The Race, The Rift, The Dollmaker and more"an exuberant adventure across time and space, busting with questions of mortality and morality, identity and biology. Told with real heart and appealingly Phythonesque humour, this is a gloriously compact tardis of a book."

– Vicki Jarrett, author of Always North"Greensmith is a head-spinning, brain-expanding journey through the universe, alternating between wildly abstract concepts and meticulously detailed character studies. Funny, resolutely British and sometimes startlingly mournful, Greensmith proves that Aliya Whiteley is capable of producing stunning work in any genre."

– Tim Major, author of Snakeskins and Hope IslandReduction

"It shrinks without sacrificing information," Hort mused over the kitchen table, waving his spoon at her before thrusting it back into the bowl of muesli.

"Would compression be a better description?" said Penelope.

"Shrinkage, compression… What did your father call it?"

"He called it reduction. But that's because he said it always reminded him of jam-making."

"I beg your pardon?"

Hort's bemused expression made her laugh. "I know. He travelled the world, he learned so much, he somehow came up with this amazing, inexplicable machine. And then he described it as being similar to the process of making jam, because he used to watch my mother do just that, and he said he was always fascinated by it."

"And how does a person make jam?"

She explained the fruit, the sugar, the boiling, the sterilising, and the wrinkle test to him. "You put a spoonful on a cold plate, leave it for a minute, and then push it with your finger. If it wrinkles, it's ready."

"I don't think this line of thought is helping much," he said. "Did your mother manipulate it in some way? Were special words involved?"

She laughed. "I don't know. I don't remember her jamming process; she died just after I was born. She was German, in fact. All the money came from her side of the family, but they didn't want anything to do with my father after she died. I think they blamed him, somehow."

"Leaving you and your father alone." Hort reached across the table and squeezed her hand. She returned the pressure. Talking was coming more easily to her, and the more she did it, the more she found to say.

"I had a brother," she said. "Leonard. I never met him. He died before I was born. I think maybe that's why— That's why I've always felt quite… lonely."

He didn't reply. His thumb stroked the back of her hand, and that was all the comfort he could have given her. It was so odd, how the smallest of gestures could be so meaningful.

"Anyway…" she said, eventually.

"Yes!" Hort dropped her hand and returned to his muesli. "Compression. Reduction. What's the difference?"

Penelope drank her tea. The kitchen was bright and warm; her favourite room in the cottage first thing in the morning. "No. You're right. It's only semantics, really. Although I wonder – if you can't describe it accurately, can you ever claim to—"

"Understand it, yes, understanding things, but that's so overrated, for me, Pea. Knowing it is better than understanding it. It's the difference between standing inside a place and looking through a window at it."

She shook her head. "Still just semantics."

"You think that language choice is just the same as swimming in a different part of the same sea?" He punctuated his thoughts by waving his spoon in the air. "All higher thought relies upon the act of communication. You can't share it, you don't know it."

"So if Einstein didn't speak or write a word for twenty years he wouldn't have been a genius?"

"A creature that does not express itself is not engaged in the act of refining itself. It's the act of translation that makes thought blossom from unformed possibility to knowledge. This is delicious," he said. "What is it?"

"Muesli."

"I like muesli best, I think. But to you, it's all just breakfast, right? A question of semantics."

"And to you, every breakfast is a unique and special moment that should be not classified in one great lump of experience," she said, smiling.

He swallowed his last mouthful and said, "Touché. But we're off topic. You're certain your father left no notes about the Vice?"

"Nothing. I sorted through his papers again recently, what with the house move."

"And there are no marks on it, no signs of construction," he mused.

"I always remember him having it. But it's possible he didn't build it." She mentally reviewed the process. The flower itself was fed through the main slot. The Vice then created a disc inside itself that, once filled with the flower's information, popped out from its underbelly. There was no obvious power source, and yet it created a record, of a kind. Each disc rattled, when shaken. The seeds inside it, she had thought. But how did it create the image? She had never been brave enough to try to open it up, although gentle explorations had revealed there was no apparent way to open it, anyway.

"Have you ever…" said Hort. "I mean, have you experienced the urge to…"

"What?"

"Never mind. We're no closer, are we? I thought if I saw your process it would throw some light on it all."

"For your own research, you mean?"

He nodded.

"You've got a machine that's similar to the Vice?"

"Oh no. I suspect the Vice is unique."

"Then what's your point of reference?" she asked him.

He looked away, his face intent with concentration – was he considering the question? "Ah," he said. "Time has passed. That flew by. You made it so easy to get lost in this space. Thank you for that. It's probably time you spoke to your daughter. She'll have something to tell you about the news."

"What news?"

"Bad news."

› • ‹

Lily didn't pick up the call.

Hort had wandered off to the rose garden, claiming she would need time alone for some reason, so Penelope switched on the laptop and did something she hadn't done in weeks. She browsed the news outlets.

There was a rare consensus between the multi-coloured harbingers of doom. A mysterious disease was sweeping across all forms of plant life on the planet. Anything that used photosynthesis to create the nutrients it needed was dying, and scientists had come together across the world to search for a cure.

The sites didn't agree on much beyond that. One claimed that genetically modified crops were responsible. Another talked off a team of British professors who had already developed a "plant vaccine" and were testing it on carrots. A third described in purple prose how people in some countries were eating their children. Articles focusing on the UK contained pictures of empty supermarket shelves and people in baseball caps with scarves over their faces carrying off large televisions. Why is it always televisions that got looted?she wondered. It didn't seem sensible. She took those reports with a pinch of salt.

But the video footage of the great rainforests of the Earth melting, oozing into a thick green paste, creating vast swamps – she couldn't stop watching them, so many of them, and although she would liked to have dismissed them as doctored they were simply too amateur to remind her of the feature films she had seen about end-of-the-world scenarios. The people filming observed quietly, spoke in hushed tones, said banal things like Look at that or There goes another. Shouldn't people have been screaming? In the trial runs for the end of the world found in fiction, from Armageddon to zombies, there had been screaming and everyone had known it was the end. Yet, in this reality, nobody online was admitting any such thing.

Penelope tried to ring her daughter again, and there was still no response. She left a standard sort of message, felt the ridiculousness of it, and decided to try her ex-husband instead. He picked up straight away.

"Pen, she's with me, here," Graham said, without preamble, and that recognisable and pragmatic tone was a vast relief. "She's sleeping now. Kieran got into a fight at a supermarket over a packet of tomatoes. He was killed, she says. It's all going to hell out there."

Who was Kieran? The fiancé, she remembered, and her gratitude that he had been killed instead of Lily was strong, and instant. How quickly everybody could be divided into people that mattered and people that didn't. "But you've got her? She's safe?"

"Listen, she says you're living in the middle of nowhere."

"I'm fine."

"No, has it reached you? The virus?" Graham's voice was raw; she wondered if he had been shouting at people. He tended to do that in bad situations, but if he could make those situations better, he did.

"No, no, there's nothing, I just turned on the news and—"

"Can we come to you? It's no good here. I've got enough petrol left in the car. We can get organised once I'm there. Supplies. Defence."

"Of course," she said. "Of course."

"We'll be leaving within the hour."

He ended the call.

It was too new a disaster to be paralysed by it, even if Graham had just made it real to her, far more real than the news could ever have managed. It only seemed sensible to go out to the rose garden and tell Hort they were expecting company.

Hort, hands in pockets, head thrown back, breathing deeply, looked different. He looked older.

"It's here already," he said. "So sad." His gaze was on the Fimbriata; the tips of the leaves were turning a vivid, unpleasant shade of green and the petals looked fatter, fleshier.

"My daughter is on her way, with my ex-husband and his wife. He thinks they'll be safer. But they won't, will they?"

"No, I'm afraid not."

"Who are you?"

"I'm not from around here."

"No."

"I'm difficult to describe, which is ironic, considering."

"All the plants are dying."

"It's a kind of virus. That's not exactly right either. It's…" He shrugged. "It's very difficult to get to the point in your language, isn't it?"

"English isn't your first language?" Of course it wasn't. He spoke it perfectly, and yet each word seemed to mean something else as it emerged from him. His mouth never quite looked at home with the sentences it produced.

"Earth isn't my first language."

"Don't be flippant," she told him. "We need to do something, we need to prepare, perhaps even get to work on a cure, is that crazy? But why not us, I mean, solutions come from the strangest places."

He stood still, regarding the rose. Then he said, "Pea, you can't save it if you stay here. I've seen it before. There is nothing we can do while we're here."

"Here, in this cottage?"

"On this planet."

"What?"

"But I can take you with me. When I leave. Which is now." She stared at him. All the things he had been saying began to percolate through her brain. "We can find a cure for it together. The Vice is the key. I'm sure of it. I've been searching for something like it for so long, across the universe."

"You're saying you're a spaceman. No, that's not the word. An alien. A space alien. What do you call yourself?"

"I call myself the Horticulturalist, Pea. And I'm here to help. I promise you. I can help your planet. But not while I'm here, and it's dying around me. And it is dying." He opened his arms to her and she walked into the comfort he offered. He smelled of coffee and toast, which was odd considering he'd had muesli. "First the plants die, then the mammals, then the insects," he said. "Did you speak to Lily?"

"She was sleeping."

"That's a shame. It was realistically your last chance for a good long while. Okay, here's the thing. I'm leaving right now, and I want you to come with me. Because nobody knows that Vice like you do. And because we make a great team." He released her, and took a step back to squint up at the sun. "I have a method for travelling with a companion. For keeping a personality as intact as possible while moving through the universe, at speed, vast distances. It's a compression of self— Damn this language!" He stamped around the rose garden. "Damn it bugger it fuck it, it's knobtanglingly difficult at times, isn't it? It's quite therapeutic for swearing in, though. You knew this was coming, Pea? Didn't you?"

Penelope thought back to the feeling through the soil, in the roots, that she had long been attributing to the war. Now it had a shape, and it was not a human catastrophe at all. Unless.

"Did people make this virus? Scientists, in a lab, that kind of thing?" she asked.

Hort smiled, and shook his head. "No. Not people. People aren't the be all and end all, you know. You're not responsible for everything. You'll understand that if you come with me. You'll have a better grasp of what it means to be human, because you won't be one any more. You'll be…" He clicked his fingers until the words came. "It's like your father said. If you're the fruit now, you'll become jam."

"Reduced," said Penelope. "Squashed."

"Intensified. And we're back to semantics. We'll take the Vice, get some answers. I'll take along the Collection, too. Keep it safe. I have the perfect place for it."

"This is bizarre," she said.

The sun was shining, the sky was blue and held perfect puffed dots of cloud, and she could hear a light rain falling in the woods. No, not rain. Not rain, after all. The branches were becoming bare, and the dripping was the sound of leaves turning to liquid and falling, in soft rhythm, to the ground. Penelope listened as she examined the Fimbriata; the petals were so soft and full, and trembling. She blew on one, and it heaved, broke its form, and splashed apart.

"It's a corruption," said Hort, which made no sense to her.

"I told them to come here. Lily. Graham."

"Could you leave a key under the mat? Or just leave the door unlocked."

It had been so difficult to believe in anything for years, apart from the flowers. There had been such fighting to control the world, and what people thought of it. Could she choose, at this moment, to not believe in Hort and the virus, of the evidence of her own eyes? It would have been easy to ignore it, go back inside the cottage, for a few minutes more, at least.

But that feeling, the feeling of something coming for her. It was here. It was time to make the decision to be a different person.

"I'll be the same in some ways, right? If you reduce me."

"Every aspect of you will be recorded in incredibly accurate detail. It's a little like the Collection. Those are still flowers, really, aren't they? Down in the basement."

"In a way."

"So you'll be you. In a way."

"How does it work?"

"I take a few – hmmmm…" Hort mused over the words, while all around them the natural world dissolved, "snapshots of you, and then you won't even feel a thing."

"That doesn't tell me much."

"I know. I'm sorry. I was attempting to be reassuring rather than accurate."

"And then what?"

"We go travelling, we get our answers, and we save the universe. Maybe even Earth, too, if we're quick enough."

She remembered what he had told her three days ago, upon his arrival. "You've been looking for a cure in the formal gardens."

"Of the universe, yes. This is a universal virus."

Other places, wiped clean of flora. Other planets.

"We could wait," she said. "We could take my daughter, too."

Hort squeezed her hand between his, and said, "No. If you're coming, you're coming now. Besides, you won't exactly feel… The emotional intensity of that connection in the same way, in your new form."

"I'll forget her?"

"You'll still care. Eventually, you won't care as much."

It was that idea that helped her to make up her mind. There were only two options open to her: stay put, and protect Lily to the end; or leave, try to save the world – the universe, even, okay, why not? – and find a way to not blame herself for leaving Lily behind. To hear not caring so much could be part of the deal. Yes, that would be possible. That could work. She could function, that way.

"Okay," she said. "What happens first?"

"It's already happened. I've taken two pictures, captures, of your personality. Just moments of thought really. It gives me all the information I need. It's an internal process for me. You haven't noticed a thing. So we're all ready to go. Just say the word."

"You took these captures without my permission?"

"I wouldn't have used them if you said no," he said. "Trust me. There's no fun in travelling with a permanently pissed-off companion. If you're coming along, it's because you want to. Because we have a job to do."

"A virus to stop," she whispered. But not on Earth, and not only for Earth.

The tree branches had melted to sludge and the trunks were starting to follow suit. The roses, all of them, were fat formless blobs in a child's painting and the smell in the air, growing stronger by the second, reminded her of petrol.

She shut her eyes tight. "Don't forget to bring the Collection."

"I won't."

"Or the Vice."

"Absolutely."

"I'm trusting you," she said, with a hint of warning, and was reminded of a little girl in a blue dress standing next to a hot tray of chocolate biscuits, fresh from the oven, with her hands clasped behind her back, promising not to touch. Lily, oh Lily, Lilium longiflorum, her Easter gift, such a generous gift considering she spent her own life so meanly, parcelled out, sorted, filed away and now about to be squashed. Squashed flat.

Compression, reduction, intensification.