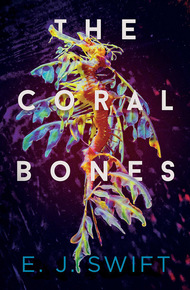

E. J. Swift is author of THE CORAL BONES, a work of eco-fiction connecting three women across the centuries by their love of the ocean, and is published by Unsung Stories.

Her other novels include PARIS ADRIFT, a tale of bartenders, time travel and the City of Light, is published by Solaris and The Osiris Project series, a speculative fiction trilogy published by Del Rey UK and Jabberwocky (US), exploring the geopolitical impacts of climate change. Book One, OSIRIS, is set in a future ocean metropolis, a failed utopia whose inhabitants believe they live on the last city on earth. The second book, CATAVEIRO, is set in South America, and expands the series to explore the world beyond Osiris. The series concludes with TAMARUQ.

THE CORAL BONES was shortlisted for the 2022 BSFA Award for Best Novel and The Kitschies Red Tentacle (Best Novel).

Three women: divided by time, connected by the ocean.

Marine biologist Hana Ishikawa is racing against time to save the coral of the Great Barrier Reef, but struggles to fight for a future in a world where so much has already been lost.

Seventeen-year-old Judith Holliman escapes the monotony of Sydney Town during the nineteenth century, when her naval captain father lets her accompany him on a voyage, unaware of the wonders and dangers she will soon encounter.

Telma Velasco is hunting for a miracle in a world ravaged by global heating: a leafy seadragon, long believed extinct, has been sighted. But as Telma investigates, she finds hope in unexpected places.

Past, present and future collide in this powerful elegy to a disappearing world – and vision of a more hopeful future.

I'm a huge fan of Emma Swift's writing, and The Coral Bones might be her best and most ambitious yet, an urgent and compelling novel across three timelines, about climate change and so much more. This one should get a whole bunch of awards. – Lavie Tidhar

"A rich and brilliant novel about the connectedness of humanity in itself and with its world: beautifully written and compellingly drawn, layering history, present day and the future with brilliancy and power. It's a novel about the climate crisis, but it's a naturalist's novel too, with some wonderfully, vividly observed writing about sealife from coral to sharks and seahorses. Just marvellous."

– Adam Roberts, author of The Thing Itself"A beautifully crafted love letter to our endangered coral reefs. E. J. Swift confirms her reputation for writing elegant, heartfelt and compelling eco-fiction."

– Anne Charnock, Arthur C. Clarke award-winning author of Dreams Before the Start of Time and Bridge 108"Beautifully realised, vivid versions of past, present and future combine in The Coral Bones to powerful effect. It gave me much to think about. I won't forget it."

– Aliya Whiteley, author of Skyward Inn and The Loosening Skin"E. J. Swift pulls no punches in this beautiful and terrifying yet boldly hopeful novel. The wonder of the Great Barrier Reef is laid out for us via a vivid multi-dimensional tour through the lenses of past, present and future."

– Vicki Jarrett, author of Always NorthHana

MAY

We found the body in an orange inflatable off the south coast of Lizard Island. Face, limbs and torso had been painted entirely white, and in black letters on the surrounding lip of plastic were the words: This is what it looks like when coral dies. In the days that followed Coral Man's appearance, I read numerous theories about his demise, and more about his desecration. He was a prophecy, a wake-up call, also an affront. Some claimed he was the work of activists, eco-warriors and the like who had been on the warpath since the beginning of the bleaching crisis. A few right-wing outliers blamed the scientific community, never to be trusted when it came to climate. One tabloid posited a radical form of protest through self-immolation, and then of course there was that singular article, which argued the words were a twisted tribute to the musician and international icon Prince, days after the anniversary of his death at his home in Minnesota.

The man was a stranger to me, but death brings unforeseen intimacy. To look at him was vertigo. Reading that message, I felt as though all the events of the days and months preceding were smashing together: the words I had said to you and withheld, the promises made and the too many I had broken. Something other would be forged in the collision. Molecular structures would split and reconfigure, just as all around us the ecosystems we had depended upon for millennia were melting, mutating, metastasising into unpredictable forms. Reading that message, it was clearer than ever to me that we had reached the brink, were poised on the very edge of the abyss, uncertain if we would fly or fall.

Did you see the story, Tess? All the major news outlets ran it, so you must have caught the headlines at least. Probably you thought of me, and probably you wished you hadn't. I'm sorry for that – I'm sorry for a lot of things. There's no reason you should have placed me at the scene, but I did in fact play a role in Coral Man's discovery. As for the media hyperbole, you're too astute to have paid much attention to that. The truth, as we both know, lies in the interstitial. To reach it, you must be prepared to go under.

Are you ready?

Then take a deep breath.

›•‹

Aaron and I were out in one of the research station dinghies, assessing the damage to the surrounding reefs after the latest bleaching event. I was already in the water, about to submerge, when we saw the inflatable. It was a hundred metres away, being slowly guided to shore by two divers, masks pushed up from their faces. Inside, we could make out something long and white and inert. Aaron gave the divers a wave and we manoeuvred our dinghy carefully around the bommie to give them a hand with their mysterious cargo. As we drew closer, it became clear that the white object was indisputably human and indisputably dead. I looked to Aaron and saw my alarm mirrored, his eyes widening with incredulity. My gut twisted. The dread that I'd been carrying all morning contracted into something hard and stony.

The first diver, a man, hailed us.

Hey, guys! Do you work here? We found this – this dude—

Just floating! Out past the reef—

The second diver was a woman. They were American – tourists, I assumed, from the island resort. Aaron assured them that we did indeed work here. That was good enough for the Americans. Aaron brought the dinghy close to the beach so I could jump out and I helped the tourists push the inflatable up on the sand. They were both white, heavily tanned, and of my parents' generation – I guessed them to be in their sixties.

As we wrestled with the inflatable in the surf, the body inside slid to an angle, making all of us swear. The soles of the feet were now pointed towards me. Beneath the paint I could see the hard skin of the heels and the softer curve of the instep, wrinkled by exposure to water. My stomach buckled again. The sand underfoot shifted with the backwash and a surge of dizziness caused me to stumble. The American man grunted, adjusting to the redistribution in mass. I'd always imagined the dead to be light, but the load was greater than you would believe one person could weigh. Sweating in the heat, hampered by the suction of our wetsuits, all three of us were breathless and panting by the time we'd got the inflatable clear of the water.

We stood there on the pristine beach, a narrow strip of sand between turquoise sea and acacia woodlands, flanking the orange inflatable with the corpse inside and the loaded message on its rim. I had to force myself to look beyond the words, to give the dead man the courtesy of acknowledgement. He was broad-shouldered and still muscular, although a degree of thickness around the waist suggested he was losing the battle against middle age. He wore board shorts, the material stiffened with streaks and gullies of white paint, and flecks of it surrounded him in a spattered halo. His eyelids were glued closed. There was no evidence that I could see of physical assault – that is, nothing to indicate murder – but I couldn't suppress that vestigial sense of foreboding. I leaned in, swallowing back my nausea. Studied the face. Thick eyebrows, neatly trimmed beard and a largish nose, a tinge of sunburn glowing through the paint. Its physiognomy, from above, not unlike the contours of a reef. There was no bloating.

Hana! called Aaron, who was still in the dinghy. It's not anyone we know?

I looked up, startled. It hadn't occurred to me that the dead man could be from our community, an acquaintance or colleague from the research station.

I don't recognise him, I called back.

We should get help, the American woman said nervously.

Of course, there is no mobile phone coverage on Lizard Island.

We were roughly halfway between the resort and the research station. In the end, Aaron had to take the dinghy around the island, and the Americans and I waited with our dead ward, moving a good few metres down the beach before seating ourselves, trying not to dwell upon the question of who he might be and how he had come to be here. Instinctively I checked the skies, but the beautiful day was holding. Our vista eastwards could have been an exact replica of the advertisement that must have brought these tourists halfway across the world: a view that completely belied the destruction Aaron had recorded only this morning. If this was irony on an existential scale, I wanted no part in it.

By now it was approaching midday, and the three of us retreated into the slim shade offered by the acacias. I heard the call of a pheasant coucal, caught a brief glimpse of the bird itself before it took flight inland, unimpressed by this incursion on its territory. The heat bore down. The wetsuit seemed to squeeze my chest ever tighter. I succumbed, peeling off the top half, then the bottom, aware of a crashing relief as the air entered my lungs with greater ease. I sat in my bikini, conscious of being nearly naked in the company of strangers; and of the corpse, which was worse somehow, as though its proximity were contagious. But anything was better than being in that skin at noon in the tropics.

The Americans watched me, then hesitantly they too rolled down the top halves of their wetsuits.

What was your name again? the woman asked.

Hana, I said.

I'm Erica. This is Bruce. We're staying at the resort.

I nodded.

We're from California, said Erica.

Brisbane.

I watched her push down the urge to ask where I was from originally. It was hardly the occasion for casual chat, but we needed to distract ourselves from the inflatable. I asked if this was their first trip to Australia. Erica said they'd visited once before, the west coast and Ningaloo.

Most people do it the other way round, I commented.

Bruce wanted to see whale sharks, said Erica. But it's true the east coast is prettier. Don't you think, Bruce?

It's pretty, sure.

How long are you staying on the island? I asked.

Seven nights. We did Cook's Look yesterday, but really we're here for the diving. We've been all over the world, the Maldives, the Red Sea… so we had to come here. It's terrible what's happening to the oceans. You know, when we started out, the reefs were pristine. There were so many corals and thousands of fish, literally thousands.

You don't see groupers and sharks now, said Bruce. Not in numbers. Not like you used to. Tell you what, there's a ton more jellies out there too.

Gives me the creeps, said Erica.

Cascades, I murmured, more to myself than to the Americans. That was the thing: bleaching was just the start of it. Maybe the Americans knew that, maybe they didn't. A quarter of all marine species depended on this habitat. When corals died, it wasn't a death in isolation. The benthos was next – all the lesser loved creatures, the millions of worms and snails and crustaceans that made their home on the reef – then the fish went, and the turtles, then the cartilaginous predators, the sharks and rays. An entire ecosystem collapsed.

But surely your government's gotta do something? said Bruce. This is gonna hit the tourism industry hard, if nothing else.

Don't get me started, I said.

There was a pause. Erica said, Anyway, I guess we're telling you things you already know. If you're a scientist here?

I don't work on the island all the time, but yeah. I'm a marine biologist.

This time the pause was longer, and I knew we were all thinking about the message on the orange inflatable. This is what it looks like when coral dies. The palette of a common clownfish, I thought. Orange plastic, white paint, black letters. The reef's most flaunted icon, for anyone familiar with its inhabitants. Given that it was the Americans who had found Coral Man – as I was already thinking of him, as the media would inevitably dub him – they would surely be suspects for his deceased state. They'd said it themselves, they cared about the oceans. And now that I had revealed my profession, doubtless the same possibility had crossed their minds about me.

I sized up the odds. Me, mid-thirties, average height, in reasonable shape from regular diving and cycling, though I'd let the latter slip more recently. I supposed it was just about conceivable to others that I might take on a hefty fifty-year-old man. The Americans were older, and saggier around the edges, but there were two of them and they were experienced in the water.

I reminded myself that Aaron was a witness, Aaron was fetching help. But now all I could think about was the man, and how he might have died. Drowning, if that were the cause, was a horrific way to go. In a rush, I remembered all the dives where something had almost gone wrong, when I'd lingered a few minutes longer than advisable at depth, or seen the shadow of something large, not yet identified, emerging from the gloom. I imagined my body pulled from the water, laid out on a slab to be named. What had this man been aware of in his final moments?

Don't think of it. I scanned the shoreline. It would be too easy to see menace in the isolation, the oppressive heat, to give in to the premonitory feeling of the day. A goanna eyed us up from further down the beach and began heading our way, its gait slow but determined. The Americans looked unsettled.

They don't bite, do they? asked Erica.

I told her the goannas weren't dangerous. The lizard stopped about fifty metres away from us, observing. Its tongue flickered in and out. Then it turned and lumbered away into the forest. After that, Erica kept checking behind her, as though the lizard might suddenly leap out from the bush.

I wished Aaron would return. My dive watch said he had been gone for twenty minutes. It felt much longer than that. I began worrying about the body in the heat. Should we have dragged it into the shade? Would it start to bloat?

Erica occupied herself with pointing out seabirds to her husband.

Is that a tern? she asked. I think it's a kind of tern. If we had the app we could check what they are.

We don't have the app, honey. We don't have our phones.

I know we don't have the app. I'm just saying, if we did—

Her gaze veered in my direction, inviting me to be her interpreter. I had no intention of taking on the role, or of telling her she was looking at two species of terns, bridled and lesser crested. The birds were fighting over a catch, their wings stretched into taut arches, talons outstretched.

I switched on the camera, which I'd had on my person when I was about to dive, and flicked through Aaron's photos. At first I was careful to keep myself oriented towards the Americans, but I quickly became immersed in the photographs. They were like everything else I had seen, from the scientific community and those media with enough of a conscience to report on the environmental crisis: image after image of bleached or dying corals. This reef had already flipped to a macroalgal state. Repeated bleaching had weakened the corals, and there weren't enough fish to keep the rapid growth of slime in check. The camera was a death memoir. I put it aside, gazed at the glittering ocean before me, the waves washing up and receding from the sand. I thought about the tourists at the extortionate resort, and wondered if they had any awareness of the massacre underwater, because that was how I thought of it: a massacre. A slow and insidious one by carbon dioxide, but a massacre nonetheless.

I was up at Lizard as a favour to Aaron. His research partner had taken ill with appendicitis and been rushed to the mainland for treatment; she wouldn't be back in the field for a few weeks. Aaron was also the sole friend I had confided in about my breakup with Tess, and doubtless he considered me in need of distractions. He was probably right, but I hadn't been looking forward to the trip. What I had seen in photographs was devastating enough. While it remained in pixels, I could cling on to delusion, maintain a barrier between the known and the potential for fallacy. I wasn't sure I had the resilience to see the damage at Lizard in person. But Aaron was focussing on signs of reef recovery, looking at the big boulder corals like porites, and that was how he sold it to me – a grain of hope in a seemingly hopeless catastrophe.

I'd flown up from Townsville the previous afternoon. I managed to pick up a last-minute connection to Cairns, and from there Aaron had booked me on the afternoon charter to Lizard, another fifty-five minutes in the air. I was the only scientist on the flight. The other passengers were visitors to the resort, where the cheapest accommodation cost around two thousand dollars a night, and private lodgings such as The Villa rose to six. Some of the resorters were Australian; the majority were from abroad, and all of them exuded the casual confidence of the rich.

There was a time when I used to enjoy listening to the conversations on these flights. In my PhD days I was shuttling back and forth from Lizard every few months, and I'd relish the excitement of my fellow travellers, their growing anticipation as we headed into the remote northern section of the reef where the islands lay like jewels against the silk of the Pacific, cradling my familiarity with a place they were about to experience for the first, and probably the only, time in their life. This occasion was not like those. I put on my headphones as soon as we were seated, and turned up the volume.

Aaron was waiting to meet me by the tiny airstrip, which spanned half the breadth of the island's south-west flank. I sank into the air-conditioned Landcruiser with a sigh of relief. Aaron leaned across to give me a hug.

Hana Ishikawa! Long time no see, partner.

Aw, it's good to see you too, mate.

Flights all good?

I could have done without the tourists.

Aaron laughed.

And how're you going on campus? Still covering Lou?

She's back from mat leave in September, thank god. I swear the undergrads get more demanding every year.

We're getting old, darl.

I shucked him on the arm.

Speak for yourself, darl.

But the reference to Lou's baby had caught me off guard, and I changed the subject. Aaron didn't ask about Tess, or how I was more generally, and for that I was grateful. Instead, we exchanged gossip about colleagues while Aaron drove the two kilometres to the research station. The island's shoulders rose up beyond the airstrip on my left, the track through eucalypts and acacia interspersed with sudden, startling glimpses of an intensely blue Pacific. Twice we stopped while a goanna ambled past, and I let my gaze roam among the forestry, spotting sunbirds and bee-eaters and once the pink cap of a fruit dove, casual harbingers of the spectacular range of wildlife on this island. Being back was dredging up a host of emotions, none of which I knew what to do with.

Aaron showed me the quad-share where I would be staying with three other women. The researchers – another coral biologist, a mantis shrimp expert, and her PhD student – were out in the field for the day. Aaron's partner's belongings had been stowed in a box by the bed, presumably awaiting her return. I pushed it into the corner. I'd seen enough of storage lately.

That night it was the weekly communal barbie. I'd already told Aaron I'd skip it. I was too nervous there would be people I knew, dreading the questions that would inevitably be asked and which I couldn't answer truthfully. Instead I stir-fried some vegetables and tofu. The kitchen had recently been repainted so I ate outside in the shade of the quad, listening to the chatter of the island's residents. I tried to settle my mind by focussing on the bird calls, picking out individuals from the cacophony. On one of my first stints here I'd been billeted with an ornithologist. I remembered her telling me how the guano from seabirds helped fertilise not only the island soil but the surrounding reefs, feeding the sponges and algae and passing nutrients all the way up the food chain. There was so much interconnection between these habitats. So many links that could be shattered.

Later in the evening I wandered down to the beach, drawn by the desire to observe, if not partake in the social niceties. I could see people milling under lantern light, converging around the grill. I'd had the idea that the barbie would be a sombre affair, almost funereal, but people were talking as usual, laughing at each other's jokes and enjoying the spread. I felt naive then, intensely aware of a weakness within me that others did not seem to share. What use would it be for the community to wring our hands and surrender to despair? The work went on. It was more important than ever.

I spotted Aaron at the centre of a group, intent on conversation. He'd always had a natural ease around people, the gift of connecting with any audience, regardless of age, culture or creed. In that moment I envied him. I saw a version of my life where I was more like Aaron, and the grief hit me like a monsoon. I watched the group for a while longer before making my way back to the quad. I went straight to bed, lying rigidly in the narrow bunk. Here, at least, there was no hollow on the other side of the mattress, no stray blond hair to find beneath the sheets. An hour or so later, the other occupants of the quad returned, bringing with them the scent of smoke and toothpaste. They moved considerately, trying not to make a noise, and I feigned sleep. The chorus of nocturnal creatures sounded clear and very close through the mosquito slats, a susurrus of insects, bush turkeys rustling in the undergrowth, the occasional squawk or screech. I lay awake until just before dawn.

GREENSMITH

BIO

Aliya Whiteley writes across many genres and lengths. Her 2014 SF-horror novella The Beauty was shortlisted for the James Tiptree and Shirley Jackson awards. The following historical-SF novella, The Arrival of Missives, was a finalist for the Campbell Memorial Award, and her very different novels The Loosening Skin and Skyward Inn were both shortlisted for the Arthur C Clarke Award. Her dark fantasy short story collection From the Neck Up was published in 2021.

She has written over one hundred published short stories that have appeared in Interzone, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Black Static, Strange Horizons, The Dark, McSweeney's Internet Tendency and The Guardian, as well as in anthologies such as Unsung Stories' 2084 and Lonely Planet's Better than Fiction.

She writes a regular non-fiction column for Interzone.

AWARDS

Aliya Whiteley has been recognised by many awards committees, including two shortlistings for the Arthur C. Clarke Award – 2022 for Skyward Inn and 2019 for The Loosening Skin

BOOK DESCRIPTION

Penelope Greensmith is a bio-librarian, responsible for a vast seed bank made possible by the mysterious Vice she inherited from her father.

She lives a small, dedicated life until the day the enigmatic and charming Horticulturalist arrives in her garden, asking to see her collection. He thinks it could hold the key to stopping a terrible plague sweeping the universe.

Soon Penelope is whisked away on an intergalactic adventure by the Horticulturalist, experiencing the vast and bizarre mysteries that lie among the stars.

But as this gentle woman searches for a way to save the universe, her daughter Lily is still on Earth, trying to track her down, and struggling to survive the terrible events unfolding there…

BLURBS

"A brilliant mind altering, intergalactic delight. Brimming with humour and flair. Greensmith marks Aliya Whiteley's distinctive talents as something to get excited about."

–Irenosen Okojie, award-winning author of Nudibranch, Butterfly Fish and Speak Gigantular

"One of the most poignant, elegiac and spiritual works of science fiction I have read all year."

– Nina Allan, award-winning writer of The Race, The Rift, The Dollmaker and more

"an exuberant adventure across time and space, busting with questions of mortality and morality, identity and biology. Told with real heart and appealingly Phythonesque humour, this is a gloriously compact tardis of a book."

– Vicki Jarrett, author of Always North

"Greensmith is a head-spinning, brain-expanding journey through the universe, alternating between wildly abstract concepts and meticulously detailed character studies. Funny, resolutely British and sometimes startlingly mournful, Greensmith proves that Aliya Whiteley is capable of producing stunning work in any genre."

– Tim Major, author of Snakeskins and Hope Island

"Aliya Whiteley takes her singular voice to the cosmos in this madly imaginative, affecting and witty novel. Greensmith's pages teem with life and wonder – it's the best kind of mind-bender."

– M.T. Hill, Author of Zero Bomb and The Breach

"A radiant, sensational samba across the stars and a paean to the wonders in the overlooked and the everyday… Penelope Greensmith will capture your heart"

– E.J. Swift, author of The Coral Bones, Paris Adrift and The Osiris Project trilogy

"Aliya Whiteley is one of the most imaginative science fiction writers of the twenty-first century. Everyone should be reading her."

– Helen Marshall, author of The Migration and Gifts for the One Who Comes After

LINK

http://www.unsungstories.co.uk/greensmith-aliya-whiteley

TWITTER HANDLES

@UnsungTweets

SAMPLE

Reduction

"It shrinks without sacrificing information," Hort mused over the kitchen table, waving his spoon at her before thrusting it back into the bowl of muesli.

"Would compression be a better description?" said Penelope.

"Shrinkage, compression… What did your father call it?"

"He called it reduction. But that's because he said it always reminded him of jam-making."

"I beg your pardon?"

Hort's bemused expression made her laugh. "I know. He travelled the world, he learned so much, he somehow came up with this amazing, inexplicable machine. And then he described it as being similar to the process of making jam, because he used to watch my mother do just that, and he said he was always fascinated by it."

"And how does a person make jam?"

She explained the fruit, the sugar, the boiling, the sterilising, and the wrinkle test to him. "You put a spoonful on a cold plate, leave it for a minute, and then push it with your finger. If it wrinkles, it's ready."

"I don't think this line of thought is helping much," he said. "Did your mother manipulate it in some way? Were special words involved?"

She laughed. "I don't know. I don't remember her jamming process; she died just after I was born. She was German, in fact. All the money came from her side of the family, but they didn't want anything to do with my father after she died. I think they blamed him, somehow."

"Leaving you and your father alone." Hort reached across the table and squeezed her hand. She returned the pressure. Talking was coming more easily to her, and the more she did it, the more she found to say.

"I had a brother," she said. "Leonard. I never met him. He died before I was born. I think maybe that's why— That's why I've always felt quite… lonely."

He didn't reply. His thumb stroked the back of her hand, and that was all the comfort he could have given her. It was so odd, how the smallest of gestures could be so meaningful.

"Anyway…" she said, eventually.

"Yes!" Hort dropped her hand and returned to his muesli. "Compression. Reduction. What's the difference?"

Penelope drank her tea. The kitchen was bright and warm; her favourite room in the cottage first thing in the morning. "No. You're right. It's only semantics, really. Although I wonder – if you can't describe it accurately, can you ever claim to—"

"Understand it, yes, understanding things, but that's so overrated, for me, Pea. Knowing it is better than understanding it. It's the difference between standing inside a place and looking through a window at it."

She shook her head. "Still just semantics."

"You think that language choice is just the same as swimming in a different part of the same sea?" He punctuated his thoughts by waving his spoon in the air. "All higher thought relies upon the act of communication. You can't share it, you don't know it."

"So if Einstein didn't speak or write a word for twenty years he wouldn't have been a genius?"

"A creature that does not express itself is not engaged in the act of refining itself. It's the act of translation that makes thought blossom from unformed possibility to knowledge. This is delicious," he said. "What is it?"

"Muesli."

"I like muesli best, I think. But to you, it's all just breakfast, right? A question of semantics."

"And to you, every breakfast is a unique and special moment that should be not classified in one great lump of experience," she said, smiling.

He swallowed his last mouthful and said, "Touché. But we're off topic. You're certain your father left no notes about the Vice?"

"Nothing. I sorted through his papers again recently, what with the house move."

"And there are no marks on it, no signs of construction," he mused.

"I always remember him having it. But it's possible he didn't build it." She mentally reviewed the process. The flower itself was fed through the main slot. The Vice then created a disc inside itself that, once filled with the flower's information, popped out from its underbelly. There was no obvious power source, and yet it created a record, of a kind. Each disc rattled, when shaken. The seeds inside it, she had thought. But how did it create the image? She had never been brave enough to try to open it up, although gentle explorations had revealed there was no apparent way to open it, anyway.

"Have you ever…" said Hort. "I mean, have you experienced the urge to…"

"What?"

"Never mind. We're no closer, are we? I thought if I saw your process it would throw some light on it all."

"For your own research, you mean?"

He nodded.

"You've got a machine that's similar to the Vice?"

"Oh no. I suspect the Vice is unique."

"Then what's your point of reference?" she asked him.

He looked away, his face intent with concentration – was he considering the question? "Ah," he said. "Time has passed. That flew by. You made it so easy to get lost in this space. Thank you for that. It's probably time you spoke to your daughter. She'll have something to tell you about the news."

"What news?"

"Bad news."

› • ‹

Lily didn't pick up the call.

Hort had wandered off to the rose garden, claiming she would need time alone for some reason, so Penelope switched on the laptop and did something she hadn't done in weeks. She browsed the news outlets.

There was a rare consensus between the multi-coloured harbingers of doom. A mysterious disease was sweeping across all forms of plant life on the planet. Anything that used photosynthesis to create the nutrients it needed was dying, and scientists had come together across the world to search for a cure.

The sites didn't agree on much beyond that. One claimed that genetically modified crops were responsible. Another talked off a team of British professors who had already developed a "plant vaccine" and were testing it on carrots. A third described in purple prose how people in some countries were eating their children. Articles focusing on the UK contained pictures of empty supermarket shelves and people in baseball caps with scarves over their faces carrying off large televisions. Why is it always televisions that got looted?she wondered. It didn't seem sensible. She took those reports with a pinch of salt.

But the video footage of the great rainforests of the Earth melting, oozing into a thick green paste, creating vast swamps – she couldn't stop watching them, so many of them, and although she would liked to have dismissed them as doctored they were simply too amateur to remind her of the feature films she had seen about end-of-the-world scenarios. The people filming observed quietly, spoke in hushed tones, said banal things like Look at that or There goes another. Shouldn't people have been screaming? In the trial runs for the end of the world found in fiction, from Armageddon to zombies, there had been screaming and everyone had known it was the end. Yet, in this reality, nobody online was admitting any such thing.

Penelope tried to ring her daughter again, and there was still no response. She left a standard sort of message, felt the ridiculousness of it, and decided to try her ex-husband instead. He picked up straight away.

"Pen, she's with me, here," Graham said, without preamble, and that recognisable and pragmatic tone was a vast relief. "She's sleeping now. Kieran got into a fight at a supermarket over a packet of tomatoes. He was killed, she says. It's all going to hell out there."

Who was Kieran? The fiancé, she remembered, and her gratitude that he had been killed instead of Lily was strong, and instant. How quickly everybody could be divided into people that mattered and people that didn't. "But you've got her? She's safe?"

"Listen, she says you're living in the middle of nowhere."

"I'm fine."

"No, has it reached you? The virus?" Graham's voice was raw; she wondered if he had been shouting at people. He tended to do that in bad situations, but if he could make those situations better, he did.

"No, no, there's nothing, I just turned on the news and—"

"Can we come to you? It's no good here. I've got enough petrol left in the car. We can get organised once I'm there. Supplies. Defence."

"Of course," she said. "Of course."

"We'll be leaving within the hour."

He ended the call.

It was too new a disaster to be paralysed by it, even if Graham had just made it real to her, far more real than the news could ever have managed. It only seemed sensible to go out to the rose garden and tell Hort they were expecting company.

Hort, hands in pockets, head thrown back, breathing deeply, looked different. He looked older.

"It's here already," he said. "So sad." His gaze was on the Fimbriata; the tips of the leaves were turning a vivid, unpleasant shade of green and the petals looked fatter, fleshier.

"My daughter is on her way, with my ex-husband and his wife. He thinks they'll be safer. But they won't, will they?"

"No, I'm afraid not."

"Who are you?"

"I'm not from around here."

"No."

"I'm difficult to describe, which is ironic, considering."

"All the plants are dying."

"It's a kind of virus. That's not exactly right either. It's…" He shrugged. "It's very difficult to get to the point in your language, isn't it?"

"English isn't your first language?" Of course it wasn't. He spoke it perfectly, and yet each word seemed to mean something else as it emerged from him. His mouth never quite looked at home with the sentences it produced.

"Earth isn't my first language."

"Don't be flippant," she told him. "We need to do something, we need to prepare, perhaps even get to work on a cure, is that crazy? But why not us, I mean, solutions come from the strangest places."

He stood still, regarding the rose. Then he said, "Pea, you can't save it if you stay here. I've seen it before. There is nothing we can do while we're here."

"Here, in this cottage?"

"On this planet."

"What?"

"But I can take you with me. When I leave. Which is now." She stared at him. All the things he had been saying began to percolate through her brain. "We can find a cure for it together. The Vice is the key. I'm sure of it. I've been searching for something like it for so long, across the universe."

"You're saying you're a spaceman. No, that's not the word. An alien. A space alien. What do you call yourself?"

"I call myself the Horticulturalist, Pea. And I'm here to help. I promise you. I can help your planet. But not while I'm here, and it's dying around me. And it is dying." He opened his arms to her and she walked into the comfort he offered. He smelled of coffee and toast, which was odd considering he'd had muesli. "First the plants die, then the mammals, then the insects," he said. "Did you speak to Lily?"

"She was sleeping."

"That's a shame. It was realistically your last chance for a good long while. Okay, here's the thing. I'm leaving right now, and I want you to come with me. Because nobody knows that Vice like you do. And because we make a great team." He released her, and took a step back to squint up at the sun. "I have a method for travelling with a companion. For keeping a personality as intact as possible while moving through the universe, at speed, vast distances. It's a compression of self— Damn this language!" He stamped around the rose garden. "Damn it bugger it fuck it, it's knobtanglingly difficult at times, isn't it? It's quite therapeutic for swearing in, though. You knew this was coming, Pea? Didn't you?"

Penelope thought back to the feeling through the soil, in the roots, that she had long been attributing to the war. Now it had a shape, and it was not a human catastrophe at all. Unless.

"Did people make this virus? Scientists, in a lab, that kind of thing?" she asked.

Hort smiled, and shook his head. "No. Not people. People aren't the be all and end all, you know. You're not responsible for everything. You'll understand that if you come with me. You'll have a better grasp of what it means to be human, because you won't be one any more. You'll be…" He clicked his fingers until the words came. "It's like your father said. If you're the fruit now, you'll become jam."

"Reduced," said Penelope. "Squashed."

"Intensified. And we're back to semantics. We'll take the Vice, get some answers. I'll take along the Collection, too. Keep it safe. I have the perfect place for it."

"This is bizarre," she said.

The sun was shining, the sky was blue and held perfect puffed dots of cloud, and she could hear a light rain falling in the woods. No, not rain. Not rain, after all. The branches were becoming bare, and the dripping was the sound of leaves turning to liquid and falling, in soft rhythm, to the ground. Penelope listened as she examined the Fimbriata; the petals were so soft and full, and trembling. She blew on one, and it heaved, broke its form, and splashed apart.

"It's a corruption," said Hort, which made no sense to her.

"I told them to come here. Lily. Graham."

"Could you leave a key under the mat? Or just leave the door unlocked."

It had been so difficult to believe in anything for years, apart from the flowers. There had been such fighting to control the world, and what people thought of it. Could she choose, at this moment, to not believe in Hort and the virus, of the evidence of her own eyes? It would have been easy to ignore it, go back inside the cottage, for a few minutes more, at least.

But that feeling, the feeling of something coming for her. It was here. It was time to make the decision to be a different person.

"I'll be the same in some ways, right? If you reduce me."

"Every aspect of you will be recorded in incredibly accurate detail. It's a little like the Collection. Those are still flowers, really, aren't they? Down in the basement."

"In a way."

"So you'll be you. In a way."

"How does it work?"

"I take a few – hmmmm…" Hort mused over the words, while all around them the natural world dissolved, "snapshots of you, and then you won't even feel a thing."

"That doesn't tell me much."

"I know. I'm sorry. I was attempting to be reassuring rather than accurate."

"And then what?"

"We go travelling, we get our answers, and we save the universe. Maybe even Earth, too, if we're quick enough."

She remembered what he had told her three days ago, upon his arrival. "You've been looking for a cure in the formal gardens."

"Of the universe, yes. This is a universal virus."

Other places, wiped clean of flora. Other planets.

"We could wait," she said. "We could take my daughter, too."

Hort squeezed her hand between his, and said, "No. If you're coming, you're coming now. Besides, you won't exactly feel… The emotional intensity of that connection in the same way, in your new form."

"I'll forget her?"

"You'll still care. Eventually, you won't care as much."

It was that idea that helped her to make up her mind. There were only two options open to her: stay put, and protect Lily to the end; or leave, try to save the world – the universe, even, okay, why not? – and find a way to not blame herself for leaving Lily behind. To hear not caring so much could be part of the deal. Yes, that would be possible. That could work. She could function, that way.

"Okay," she said. "What happens first?"

"It's already happened. I've taken two pictures, captures, of your personality. Just moments of thought really. It gives me all the information I need. It's an internal process for me. You haven't noticed a thing. So we're all ready to go. Just say the word."

"You took these captures without my permission?"

"I wouldn't have used them if you said no," he said. "Trust me. There's no fun in travelling with a permanently pissed-off companion. If you're coming along, it's because you want to. Because we have a job to do."

"A virus to stop," she whispered. But not on Earth, and not only for Earth.

The tree branches had melted to sludge and the trunks were starting to follow suit. The roses, all of them, were fat formless blobs in a child's painting and the smell in the air, growing stronger by the second, reminded her of petrol.

She shut her eyes tight. "Don't forget to bring the Collection."

"I won't."

"Or the Vice."

"Absolutely."

"I'm trusting you," she said, with a hint of warning, and was reminded of a little girl in a blue dress standing next to a hot tray of chocolate biscuits, fresh from the oven, with her hands clasped behind her back, promising not to touch. Lily, oh Lily, Lilium longiflorum, her Easter gift, such a generous gift considering she spent her own life so meanly, parcelled out, sorted, filed away and now about to be squashed. Squashed flat.

Compression, reduction, intensification.