Cara Hoffman is the author of three New York Times Editors' Choice novels; the most recent, Running, was named a Best Book of the Year by Esquire. She first received national attention in 2011 with the publication of So Much Pretty, which sparked a national dialogue on violence and retribution and was named a Best Novel of the Year by the New York Times Book Review. Her second novel, Be Safe I Love You, was nominated for a Folio Prize, named one of the Five Best Modern War Novels, and awarded a Sundance Global Filmmaking Award. A MacDowell Fellow and an Edward Albee Fellow, she has lectured at Oxford University's Rhodes Global Scholars Symposium and at the Renewing the Anarchist Tradition Conference. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Paris Review, BOMB, Bookforum, Rolling Stone, Daily Beast, and on NPR. A founding editor of the Anarchist Review of Books, and part of the Athens Workshop collective, she lives in Athens, Greece, with her partner.

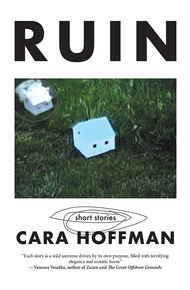

A little girl who disguises herself as an old man, an addict who collects dollhouse furniture, a crime reporter confronted by a talking dog, a painter trying to prove the non-existence of god, and lovers in a penal colony who communicate through technical drawings—these are just a few of the characters who live among the ruins. RUIN is both bracingly timely and eerily timeless in its examination of an American state in free fall, unsparing in its disregard for broken institutions, while shining with compassion for all who are left in their wake. Cara Hoffman's short fictions are brutal, surreal, hilarious, and transgressive, celebrating the sharp beauty of outsiders and the infinitely creative ways humans muster psychic resistance under oppressive conditions. The ultimate effect of these ten interconnected stories is one of invigoration and a sense of possibilities—hope for a new world extracted from the rubble of the old.

"One should not pick favorites, but I'll say it anyway: Cara Hoffman is my favorite living American writer. In her latest work, RUIN, each story is a wild universe driven by its own purpose, filled with terrifying elegance and ecstatic harm. I never wonder why what she's telling me matters. Brilliant and anti-redemptive, she traces the desire of her characters with surgical dexterity, each red line exposing life."

– Vanessa Veselka, author of the National Book Award–nominated The Great Offshore Grounds"Hoffman writes with a restraint that makes poetry of pain."

– New York Times Book Review"Tough, scarred, feral and sexy. The book and the characters refuse to conform and like in all good outlaw literature [Hoffman] takes sharp aim at the contemporary culture's willingness to do so."

– Justin Torres, author of We the Animals"Hoffman maps the atmosphere of paranoia that descends on a formerly tranquil town as she moves deftly between its inhabitants."

– New Yorker"Hoffman writes like a dream—a disturbing, emotionally charged dream that resolves into a surprisingly satisfying and redemptive vision."

– Wall Street JournalWAKING

After the boys had taken their flushed faces and the lingering spirits of their breath down the steps and back to the car, we would stay up and watch the black-and-white films we had made, projected against the gray cement of the basement wall. It was as if the night were only just now starting, at one or two in the morning, and we were suddenly entirely ourselves. The projector hummed and clacked. The focus was primitive, and we dealt with it by moving the entire apparatus forward or backwards on its folding chair. The outside shots were often overexposed. Sometimes we watched these films projected against a mirror that hung near the laundry room door. Sometimes against a sheet. Sometimes I would read a novel out loud while we went through every reel, over and over. The Sheltering Sky. The Trial. And all the while fields flashed by, birds flew, fires burned, bicycles raced past, eyes blinked and mouths smiled. Image after image made of light.

This would end around nine or ten in the morning and then we would go outside, sleepless and energized, to walk beside the stone-colored river. To walk along the trails. Sometimes we would shoot while we walked. Stills, super eight, Polaroids. Polaroids, she said, said everything. Their form alone, their very being. The subject of the photograph itself was irrelevant. It was how it came to be, she said. We filmed Polaroids as they developed. Oversaturated, grotesque, pulling their plastic genius into the silent light.

And we never talked about the boys, once they were gone. We talked about the fastest way to get through school. You can, in tenth grade, graduate. You can. You don't even need perfect grades, just mediocre grades in upper-level courses. But what would we do then? What would we do then? I asked. She shook her head and smirked at me.

Stand over there, she said, pointing to a field of Queen Anne's Lace. Go into the middle of it. Kneel. Stand. Stand with your head turned. Take off your coat. Put it back on. Do that thing with your arms where they look like they spin all the way around in front of you. Good.

We didn't think to show them the films. We didn't film them. We didn't give them books to read. We didn't talk in the same tone of voice to them or when they were around. We said, Come over. Or we said, We'll meet you. We said, We'll be over later. We didn't care what they did. We didn't care where they were when they weren't with us. Disinterest sometimes made it necessary to terminate and replace. There was always another boy. Lying on the couch, sitting in the movie theater, or in the car. With the clothes they wore, with the seven-day stubble, with stereo equipment and various talents, or interests, gleaned from television. There was always another with his own "identity," immediate and plastic like a Polaroid.

I remember the silent lips parting and the gray smoke drifting out. I remember a shot, several seconds on the reel, of a girl skidding across the asphalt on her shin, grinning from the adrenaline before she took the skateboard up the halfpipe again. I can remember the shot of her lying in the grass laughing, her face wide and bright.

Run. And while you run, take off your clothes, till you are naked when you reach that tree, and then duck down in the grass to make it look like you were swallowed up by the earth. Good.

When the boys had taken their soft skin and their swollen mouths away, we would walk outside in the dark. We would walk through the empty neighborhoods shining beneath the street-lights. Until we reached the abandoned downtown. The parking lots beneath the constellations. The tall buildings cut out against the black sky. The cool air. The expanse of concrete. This is how we walked then. In an enormous loop that led back to the pools and gardens and fountains of the west side. And we swam behind our neighbor's houses, our quiet laughter drowned by the sounds of crickets. The smell of grass and chlorine, and our breasts were weightless in the water, like they weren't even there.

You can finish college at twenty. You can. You don't even need good grades. Just mediocre grades. You can finish at nineteen if you take twenty-four credits a semester. Then you're done. And you can go to graduate school then. You can finish grad school at twenty-two. You can have your PhD by twenty-three. You can. You simply can. You can have at least three or four books written by then. You can be working for the Associated Press. You can study at a conservatory. You can sell guns. You can work in an orphanage. Smuggle spice out of the East.

We would make it home in those last crepuscular hours and hunch over the sink gulping cold water from the tap. We would sleep side by side on the floor in long white V-neck T-shirts. Our eyes shut, reading an invisible page. Our eyelashes resting against the tops of our cheekbones. Our mouths open, sucking in the night.

We slept this way until we saw how the boys were coming into finer focus. They pressed their bodies against our jeans in hayfields behind the monastery at night, and we saw how they could be made beautiful. Inside the monastery basement, white candles burned for the dead, and outside in the fields the boys were ghostly images whose fascination lay in their unfolding and hardening form. But they were as yet interchangeable. Your fist closed around one the same as any another. And only one or two required further study, or became sentimental items in their familiarity. Became desired. And once desired, ruined our sleep. Ruined our sleepless wandering.

It was like this in East Berlin, she'd said about the boys. She'd been in Berlin for a summer studying art. The wall was still standing then and she'd written our names on it.