Joshua Viola is a 2021 Splatterpunk Award nominee, Colorado Book Award winner, and editor of the StokerCon™ 2021 Souvenir Anthology. He is the co-author of the Denver Moon series with Warren Hammond, and the co-author of the True Believers comic book series with Stephen Graham Jones. As a video game artist, he worked on Pirates of the Caribbean: Call of the Kraken, Smurfs' Grabber and TARGET: Terror. He is also a film producer, with his upcoming project being Deathgasm II: Goremageddon, the eagerly awaited sequel to the cult classic. Viola is the owner and chief editor of Hex Publishers in Denver, Colorado.

Awards and bestsellers lists:

-2022 Colorado Book Award winner

-2021 Splatterpunk Award nominee

-2019 Best Book Awards winner

-2017 Independent Publisher Book Awards winner

-2016 International Book Awards winner

-2015 USA Best Book Awards winner

-Denver Post bestseller

Ancient peoples knew there were lands given over to shadow and spirit. The world is full of haunted places that exact a terrible toll on trespassers. Our forebears paid a heavy price to earn the wisdom and the warning they bequeathed to future generations. Time transformed their precious knowledge into superstition, but there are those whose hearts beat in rhythm with the past and whose vision is not clouded by modernity. Seeking to reclaim humanity's early secrets, the Umbra Arca Society was forged. For centuries, this private league of explorers dedicated their lives to uncovering the oldest mysteries of the Americas. Armed with boldness and guile, and equipped with only a compass, a journal, and devotion to truth, these adventurers braved cursed landscapes, dared unnatural adversaries, and exposed hidden civilizations.

Many did not survive.

None were forgotten.

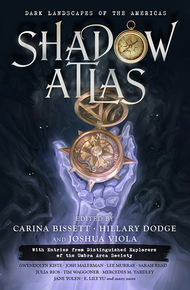

Their stories are maps revealing the topography and contours of landscapes unimaginable and dark. The Shadow Atlas collects their adventures.

The premise of Shadow Atlas: Dark Landscapes of the Americas electrifies. Secret explorers come back from all corners of the Western Hemisphere with tales of encounters "with sinister legends and harrowing mythological creatures," as Kirkus Reviews enthuses. Sumptuously illustrated throughout by Aaron Lovett, Shadow Atlas compiles contributions from a jaw-dropping who's-who of fantasy and horror, among them Josh Malerman, Jane Yolen, Tim Waggoner, Lee Murray, Julia Rios, and Christina Sng. Get these maps and go where they take you. – Mike Allen

"A host of sublime writers and settings create an entertainingly macabre collection."

– KIRKUS REVIEWS"Think The DaVinci Code or Indiana Jones, but with more literary force."

– MIDWEST BOOK REVIEW"Dead serious in its horror, yet delightful and inviting in its design and conceit, Shadow Atlas is a rare, beguiling treat, a collective fantasy with teeth, vision, and grounded in urgent, ancient truths."

– BOOKLIFE REVIEWSDear Editors:

Before publishing the pages I've included from the Shadow Atlas, it is imperative to know more about the book's origins, the Umbra Arca Society, and the man behind the hoax.

Few readers require an introduction to Professor Donald Sorensen. He researched and wrote in many fields—archaeology, history, and anthropology, of course; but also computer encryption, world finance, travel, numismatics, and equine sports. Sorensen had the good fortune of being that rarest of constructions, an academic embraced by popular culture. A precious few will argue his penchant for showmanship denigrated his scholarship. Many more offer it as final proof of his genius. He was Indiana Jones and Inigo Jones, P.T. Barnum and Barnum Brown, Andy Kaufman and Hans Kaufmann.

And I'm sorry to say, in the end, my dear mentor and colleague—my friend—Donald Sorensen was quite insane.

"Not content with the four corners of the world, I went looking for the fifth."

The quote is among Professor Sorensen's most famous, engraved even upon his cenotaph erected last year at Woodlawn Cemetery. Very few know its first recorded attribution comes from 1953, in an excised portion of Tenzing's famous memoir. If the redacted writing is to be believed (Evidence exists that Professor Sorensen paid Tenzing a considerable sum to add the fictional encounter into his memoir, though if this is true, we can only hope he got his money back when the author failed to follow through on the prank.), Sir Edmund Hillary and his Sherpa guide heard these words just as they reached the outcropping of rock near Everest's summit where a twenty-year-old Sorensen lounged like a man in a hammock. I bring up this anecdote not only as the perfect early example of the professor's mischievousness and flair, but perhaps as a dark foreshadowing of his desire to insert himself into history's great moments. Indeed, it may even give evidence of a troubling psychosis: if one cannot participate in history, then one must reinvent it, with one's own life rough-hewn into the preferred narrative.

If you do not comprehend the difficulty of the accusations I must make, then perhaps a brief self-introduction is in order. Professor Sorensen took me under his wing when he was forty years old and preparing for a sabbatical expedition into the Andes. At twenty-two, I was among seven graduate students who accompanied him as assistants. The other six are dead a long time now, but there are nights when I see their faces as I remember them best, revealed by a campfire in some cave or on some mountain crag, wide-eyed and hunched toward the man who favored us through the night with his voice. In those romantic climes, his mere presence turned the most unpromising of places into an ashram. We listened to strange tales of mythology and folklore, bits of incidental knowledge about geography and geology, little immoral parables regarding vanished tribes and fallen cities that brought forth the most delicious shiver. Call it a little touch of Sorensen in the night.

We'd forged our way high into the Andes and made camp for the night. Everyone had gone to bed when Sorensen's chanting woke us. We poked our heads from our tents in unison, looked at each other and then at our teacher. I might say shaman, for he had stripped himself almost naked and sat on the cold ground in the posture of a yogi, his spine rigid, his knees drawn tight against his chest, his palms sweeping the air above his head. My training being in archaeology, I had competence in Latin and Greek, but the chant was in neither language. I had a sense the words must be quite old, each syllable among the world's many dead things that found life again through Sorensen's benefaction.

To our great fortune, my colleague Samantha was a linguist, an expert in countless tongues. She stood to my left, and began whispering a fascinating translation—

—for kingdoms conserve

power, light, coins,

and the memory of ruin.

It is thin as paper,

as full as a coffin,

holds centuries

as if they are weightless.

And it will help you find

the way home,

even if it is not yours.

Samantha stopped translating. Her brows furrowed.

"What is it? What is he talking about?"

"Something called the Shadow Atlas," she said with a great deal of uncertainty in her tone.

We repeated the name amongst ourselves. Our supplies included any number of maps, many of dubious origin and quality. But we'd never heard of anything called a Shadow Atlas. Professor Sorensen went on chanting for another twenty minutes, but we found no elucidation there. Then he stopped and unfolded himself, noticed our attention, and smiled.

"I'm sorry if I disturbed your sleep," he said, and walked past us to enter his tent.

The next morning none of us spoke of what had happened, believing Sorensen would bring the matter up on his own time. But I was always the impatient and impetuous apostle, the professor's Peter, and two days later I took it upon myself to question him outright. Our band had found a mountain pool of crystal-clear water where we stopped to refresh ourselves. Sorensen knelt by himself, splashing his face and arms. He seemed oblivious to my approach as I crouched beside him. Staring down at my distorted reflection, I said, "What is the Shadow Atlas?"

Sorensen went on splashing and scrubbing his face. He continued for half a minute, and I feared he might not have heard me. Just before I dared repeat the question, however, he said, "Seek out Umbra Arca, and you will know."

The answer had an air of simplicity, as if I'd asked a dullard's question whose answer could be found in the index of National Geographic. He then stood and walked away, leaving me to mull the words.

Umbra Arca.

Shadow Cabinet?

Shadow Box?

A sense of shame stole over me. I'd been arrogant to ask the question, and he'd answered my vanity and presumption with a nonsensical response. I tell you no amount of water from the mountain pool could cool the heat from my cheeks that day.

I'll not demonstrate all the ways Donald could be cruel in his jests when directed at inferiors in need of a comeuppance. Doing so might make this entire letter seem nothing more than justification for a non-existent personal grudge. What I wish to bring to light is the difficulty in determining early evidence of mental illness in a man well-known for "playing the long game" when it comes to sowing the seeds of his pranks. This is, after all, the same person who began manufacturing and planting so-called Atlantean artifacts off the coast of Bimini in 1985, for the express purpose of fabricating the discovery of that ancient city in 2010. Who contemplates or proceeds with a hoax whose payoff won't happen for another twenty-five years? Is such a deed evidence of genius—or madness?

You'll remember his serious press conferences, and the fawning admiration of media around the world. You'll recall the experts shaking their heads in disbelief as radio carbon dating proved the authenticity of the pottery and the DNA testing on the skeletal remains that demonstrated a Mediterranean origin. The sensationalism proved so great that the Penguin Classics edition of Plato's Timaeus and Critias, which contains the only ancient references to Atlantis, made it onto The New York Times Best Sellers list for one week.

Sorensen staggered his revelations in one amazement after another, building a fever pitch of astonishment over the course of two months. No professor, no archaeologist, no expert stood against him in the end. And once he had them all won over, once he had them all professing Atlantis must be true, Donald pivoted to laugh in their face.

What is this world's delight?

Lightning that mocks the night,

Brief even as bright.

I must admit those exquisite lines from Shelley crossed my mind as I considered the short fire of the joke's payoff against the long time spent gathering its kindling. How could there not be some genuine mental illness at work, a creative monomania at the core of his being?

But it would be a few more years before I realized I, too, had fallen victim to it.

Twenty-five years is the mere blink of the eye compared to the decades he spent developing the Umbra Arca hoax that came to pepper every public reading, lecture, and interview he gave between 2011 and late 2019, in media appearances that ranged from CNN and CSPAN to obscure YouTube channels pushing biblical conspiracies. His many perplexing pronouncements during this period would cripple the reputation of any scholar but Sorensen. Rather than greeting him with scorn, however, it seemed the public abetted him. No doubt they believed he was joking again, and this time they wanted in on it from the start.

I'm afraid I alone have that particular privilege.

As time went on, my relationship with Donald changed. I went from student assistant to colleague and friend. Our adventures together were not without their improbable escapes, but more often than not we dwelt in the bowels of libraries rather than the Earth. "It will never cease to amaze me," he often said, looking up from some forgotten tome, "how preserving knowledge in books is the surest way to guarantee it will be lost."

In 1965, we went to Morocco, granted special access to the al-Qarawiyyin Library. So few scholars receive such an invite, but even then Donald's reputation opened the most imposing of doors. Though he claimed to be visiting for the first time, it soon became clear my cherished friend was lying. He navigated the labyrinth of rooms with too much certainty and had an uncanny knack for discovering hidden passages. I said nothing, however, too overcome by giddiness to be in the world's oldest library with its shelves of arcane wonder.

We were questing after a rumored but otherwise unknown work by Averroes, and I sat alone resting my eyes from exhaustion when Sorensen brought forth a massive book, bound in cracked leather and sealed with a peculiar iron clasp that resembled the first known compass dating back to the Han Dynasty. I didn't need Donald to draw my attention to it, but he did so anyway.

"Magnificent, isn't it? I don't know if you ever read the monograph I wrote on book clasps a few years back."

"I somehow missed it," I said.

"It's quite the topic. Clasps have a wonderful variation and history. Here you can see the prong's forked spacer implies a creation date of about 1360, which I'm sure is correct. The clasp's presence, however, makes the volume appear far younger than its contents. The book's design is comprised of various cultural techniques passed down through the ages. Each of its custodians applied their own methods for maintaining the tome."

"What is this book?"

"Come, Dane," he said. "You know all too well. I told you once."

Trying to recall our conversations over the years was difficult then, almost impossible now. Defeated, I could only shrug and ready myself for a serving of his disappointment.

Instead, he smiled and said, "Umbra Arca."

It was as if our time in the Andes happened the day before rather than years. "The Shadow Atlas," I said, rising.

"Few have ever seen one, my friend."

The leather was stamped with the imprint of an unspecified map, and there was no writing on the spine or cover.

"Do you mean there's more than one?"

"Four," Sorensen said. "One for each corner of the world. One for each of Umbra Arca's scriptoriums."

"You make it sound like an organization, Donald."

"Humanity's oldest, I should think. Perhaps you might call Umbra Arca humanity itself."

"I don't understand."

"Think of it this way," he said. "Adventure and exploration are the heart of Umbra Arca's mission. True humanity was invented the moment our first ancestor walked toward the horizon not in a search for food or shelter, but from a simple desire to see what waited. Umbra Arca came into existence on that day, too."

I smiled at the simple grandeur of his vision, though I didn't reflect on his word choice of invented rather than born until years later. He sketched for me some sense of how this secret society was organized. Those familiar with Sorensen's more recent and rich elaborations may be surprised at the paltry details he provided at the time. I suppose his imagination or his madness was only just hatching the concept of the scriptoriums, the directorship, the daring field agents, and the sober scribes who recorded their stories. I can only say that when he introduced Umbra Arca and its purported Shadow Atlas to me, the society seemed to consist of perhaps one hundred members. As the hoax or delusion grew in his mind, Umbra Arca became a clandestine organization with thousands of initiates ranging across the globe on an eternal mission into the world's twilight places. The details accreted like layers of ash from multiple eruptions of Sorensen's overheated mind. You may remember his last rambling lecture at Naropa University just over a year ago, mere months before his disappearance and presumed death. Not only did he declare the Naropa University library's basement to be the location of the Western Scriptorium, he went on to say:

The oath they take…it is a blood vow. Blood of all blood…You will know an adherent of Umbra Arca by the compass in their hands. The compass pointer is needle-sharp, its tip stained red with blood drawn from the initiate's own palm. It never points true North, but it always points in the direction of true desire. There is a song they sing, you see. I will reveal part of it now. I have never before done so. A book of pages blank and white, a yellow day, a purple night, and a road of flame before us. That is as much of the song as I dare give you, but perhaps it is enough to let you hear hints of its melody upon the wind.

I could only shake my head when I heard this nonsense. I retained enough love for Donald that I almost wept at this insight into the ruined state of his mind. Then I heard the sustained applause of the crowd and the way they chanted Umbra Arca and Shadow Atlas like cheers at a football game. I wanted to believe it was the crowd going along with the delusions of a very old man, the way the citizens of San Francisco showed obeisance to their beloved Emperor Norton. But there was too much enthusiasm in their response, too much fervor. Even very intelligent people can be swayed by charisma. Innumerable cults demonstrate this fact. Hoaxes take root, turn into conspiracies and, if very pernicious, become religions.

This possibility remains my greatest fear regarding Umbra Arca: watching some new belief system rise before me. I understand Umbra Arca's power to work upon the mind, being its first convert and for many years its most devout—and perhaps only—follower.

I take you back to that moment in the al-Qarawiyyin Library, as I stood over the iron-clasped book my dear friend, colleague, and mentor Donald Sorensen called the Shadow Atlas. My imagination was aflame even without the embellishing details that came so much later. I was enchanted by the idea of underground societies and secret knowledge, and how could I doubt the veracity of the great Professor Sorensen? Above all else, did I not have my right palm resting upon the Shadow Atlas itself? Some of my life's great leaps of faith seem naive in hindsight, but any empiricist would have given the ancient book and Sorensen's explanation credence.

"Let me open it."

"What do you expect to find?"

"Lost maps?"

"Ah," he said. "Maps can take many forms and shapes, my friend. The Shadow Atlas charts a different geography. We members of Umbra Arca are cartographers of truth."

Whether or not I stifled a gasp at this revelation is irrelevant. "You mean to say that you belong to Umbra Arca?"

"I do, and I have long sought to bring in another initiate. I considered you long ago, Dane. That morning by the water, when you asked your question. Every question is a footstep, and I know you to be a fond traveler."

I moved to undo the clasp, but Donald grabbed my wrist. "Open the book before it's time, and you will find only heartbreak."

"In what sense?"

"In the sense that you've been judged unworthy of its secrets."

"But how can I possibly know when I'm ready? Will you tell me?"

Smiling, he said, "I may be quite dead before that date. The Shadow Atlas itself will tell you."

I laughed at the notion. "Oh? Will a little voice speak to me from within?"

"No," he said, pressing his lips together tight.

"Then how?"

"One day, you will find the clasp has fallen away on its own. When that moment comes, you may open the book. Not a moment before."

I vowed it would be so. My intrigue outweighed common sense and reason. I did not even question how Donald took the book from the library. Doing so only reinforced the notion that the library doubled as a secret scriptorium, and since my friend belonged to Umbra Arca's hierarchy, he did as he pleased. Now, of course, I conceive of a very different reason the librarians never opposed the book's removal. Why would they care about a volume that never belonged to their collection in the first place?

I'll not detail how our relationship soured in the ensuing years. The tensions between aging men are seldom interesting to uninvolved parties. For the longest time I kept true to my word. I put the Shadow Atlas on a table under glass in my library. How foolish I must have looked, checking on it at odd hours of the day and night, perpetually hopeful the clasp would be open.

I saw Donald less with each passing year. He kept to his adventures and increasing notoriety, while I became a prized guest lecturer at several universities. No matter how many honorary chairs I held, however, my true self-worth rested on being a member of Umbra Arca. Was anyone ever so self-deluded? Sorensen never introduced me to another member of Umbra Arca, nor did I ever attend a single meeting of this secret society. I was given no tasks which I might fulfill in order to prove my worthiness. As far as I knew, being a part of Umbra Arca just meant waking up and going to bed. I lacked even something as juvenile as a secret handshake.

But I had the Shadow Atlas, and I continued to check every day through the 1960s, the 70s, the 80s, the 90s. The century changed, but I did not. Day after day, year after year, I never failed to check the clasp of the Shadow Atlas.

It was always locked.

Until the day it wasn't.

It happened almost at the same time Donald began talking about Umbra Arca to the public. I rushed to the desk, removed the glass lid, and almost hyperventilated. To say I opened the book is accurate, but it diminishes the reality of at least ten false starts, the pulling back of the hand to touch my chest, the spasm of muscles in the forearms, the growing tremor that palsied the fingers. Yes, I opened the book and beheld an interior composed like a Mayan codex, a concertina of hu'un sheets stitched to the leather cover with a weave reminiscent of something from the Middle Ages.

The first page was blank. It was crinkly, almost brittle, and foxing everywhere.

The next page was identical. So, too, the third and fourth.

I began to treat each empty page with less care as I turned them, shouting, "It can't be!"

Had I failed Umbra Arca at the last minute? What else explained how the pages were bled of their precious, impossible contents? This secret society was such a concrete concept in my mind that I couldn't conceive it was never real, and that the Shadow Atlas was a clever invention built around some ancient book Donald found whose pages happened to be blank. No doubt he'd designed the clasp with a hidden spring meant to trigger according to some internal clock.

No, my self-excoriation did not allow me to entertain such thoughts at all. It would in fact be a full year before I allowed myself to consider alternative notions about the book and the organization supposedly behind it.

One night, I sat at my computer listening to a podcast. Donald was supposed to be addressing the finer points of stamp collecting, but he kept interrupting himself and his interviewer with long ramblings about Umbra Arca and details he'd never told me about the Shadow Atlas. He suggested that the Umbra Arca compass becomes one with its holder. That they can feel where they must go, and their very bones guide them to their destinations. He even suggested that the book's pages themselves are a compass, and the kineograph at the top of each page points to the story's corresponding region depending on where the reader is standing. But most interesting, he blathered on about a force or mysticism at play, linking all of the tomes together. When a new entry is added to a volume, it mysteriously appears in the others.

For just a moment, I shook my head, angered that he'd withheld the information from me all these years. Then I realized the grave possibility it was a terrible hoax concocted by a man who'd never been in his right mind. The more I listened, the more convinced I became. A fit of pique made me determined to destroy the Shadow Atlas. I resolved to burn the book's pages one at a time. I tore out the first and brought it to a candle. Before the paper caught, however, the flame's heat revealed words composed in invisible ink.

It was a table of contents.

Rushing but careful, I warmed every page and discovered what seemed to be a collection of stories. Tales of horror and adventure, folklore and myth. I read through the night, remembering those youthful nights hearing him at a campfire, holding court. Some of the entries were very old, but others were dated more recently. Had Sorensen gone so far as to orchestrate the addition of new, modern pages for me to find, decades after he'd gifted me the book, to fulfill this notion that the book updates itself with each new entry? Had he hired someone to break into my home to accomplish this task?

Of that, I have no doubt.

I now offer these stories and field guide pages in the exact order I uncovered them, including Sorensen's own notes, journal entries, and drawings he attached to various pages without a detail added or subtracted. I cannot say if sharing Sorensen's Shadow Atlas with the world is an act of love or an ode to the hatred for the man I once esteemed my friend and mentor. It is, at the very least, an offer of lies for the sake of a truth that must be told.

Respectfully,

Dr. Dane Essa