Lee Murray is a multi-award-winning author-editor, essayist, screenwriter, and poet from Aotearoa-New Zealand. A USA Today Bestselling author, Shirley Jackson and five-time Bram Stoker Awards® winner, she is an NZSA Honorary Literary Fellow, and a Grimshaw Sargeson Fellow. Lee lives in the sunny Bay of Plenty with her well-behaved family and a naughty dog.

Geneve Flynn is a multi-award-winning speculative fiction editor, author, and poet. Her work has won two Bram Stoker Awards®, a Shirley Jackson Award, and an Aurealis Award. She's also been shortlisted or nominated for the British Fantasy, Locus, Australian Shadows, Ditmar, Elgin, and Rhysling Awards, as well as the Pushcart Prize. She is a recipient of the 2022 Queensland Writers Fellowship.

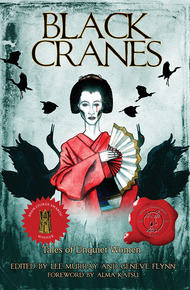

Black Cranes has won The Bram Stoker Award and The Shirley Jackson Award. It was also a finalist for the Aurealis, Australian Shadows, Locus, and British Fantasy awards.

Almond-eyed celestial, the filial daughter, the perfect wife.

Quiet, submissive, demure.

In Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women, Southeast Asian writers of horror both embrace and reject these traditional roles in a unique collection of stories which dissect their experiences of 'otherness', be it in the colour of their skin, the angle of their cheekbones, the things they dare to write, or the places they have made for themselves in the world.

Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women is a dark and intimate exploration of what it is to be a perpetual outsider.

I'm thrilled to include in this StoryBundle the groundbreaking anthology from Lee Murray and Geneve Flynn that swept the Bram Stoker and Shirley Jackson awards. Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women smashed stereotypes surrounding Asian women to smithereens even as the authors drew on their cultures and mythologies to open new frontiers in fear. This book and the stories within it were nominated for many more honors, with the Eugie Foster Award bestowed on Elaine Cuyegkeng's hauntingly beautiful opener, "The Genetic Alchemist's Daughter." – Mike Allen

"The beauty of this collection is in the diversity of the voices and the individuality and uniqueness of each story coming together in one book."

– Tor Nightfire"The preconceived notions of both the authors' identities and of the limitations of the horror genre itself will be smashed to pieces, to the delight of readers."

– Becky Spratford for the Library Journal"Resonates with bold originality throughout."

– Space & Time MagazineFRANGIPANI WISHES

Lee Murray

Some things you knew already. Some things you knew before you were born; they were revealed to you in the rhythm of your mother's heartbeat and in the echoes of her sighs. Later, you heard it in the closing of doors, in the scuff of a suitcase, and the low hum of a ceiling fan.

the bitterness of smiles / the perfidy of eyes

That was back when you lived with your bones squeezed sideways into the spaces between the floorboards of your father's villa, cowering from the sharp tongues of lesser wives and the cruel taunts of your half-sisters. Back when you were waiting to live, when you lived and waited, comforted by the soft scents of your silly frangipani wishes. Embroidering silk dreams, you waited, listening for the hundred-year typhoons that whipped across the harbour, tugging at rooftops, flattening shanties, and stealing away souls. Because only when the winds raged and the waters of the harbour thrashed, only when the villa rattled with unease, only then were the ghosts quiet. Only then, were you able to breathe.

* * *

Since the moment you were born, generations of hungry ghosts swirled around you, teasing the air, your breath, your hair. Not your fault, although First Wife and Little Wife and the entanglements who dwelled in your father's villa, those living repositories of secrets, they blamed you still. They whispered behind their hands, hiding smiling teeth, muttering, uttering, chattering. Your mother had unleashed them, they said, spawned them as she spawned you, let the starving ghosts escape into the night. A hundred dragon's teeth could not drive out such demons. Nor a thousand dragon teeth ground to powdered dust. It was as well she was gone.

Your mother might be a ghost herself; you didn't know. No one had thought to tell you, although they said other things—mean, sunken, tortured things. Things with thin bony limbs and slender necks. Swollen bloated-bellied things which wormed their way beneath your ribs, pushing aside your lungs, where they took up residence: pulsing, and pulsing, and pulsing… You learned to live with them, the tortured, swirling wisps of ghosts and the ugly, swollen pustules lodged under your heart, while you waited for the tempests, while you waited to live, in your father's villa on the hillside.

A cousin came to the villa. He worked in the textile business and came to weft and weave words with your father. A distant cousin, although not so distant. Little Wife called for you, she liked to see you underfoot, so you squeezed your way up to where the living roamed, hauling yourself from the damp crawlspace, through the gaps in the floorboards. Scrubbed and pretty, you served Distant Cousin tea in the salon, hands trembling with reverence, since he was your father's guest. You served the sweet red bean cakes that were everyone's favourite. You nibbled on the crumbs, caught the rifts of conversations, and a waft of sultry sandalwood. After that, Distant Cousin stayed on, stopping to play mah-jong with your father and his friends, their voices murmuring, and the tiles clattering long into the night.

the harbour / glints / in his eyes

Hello, little cousin, he whispered as he passed you days later in the hall, setting your insides aflutter, like the wings of the skylark Little Wife kept in a domed teak cage in her room. Just in time, you remembered to drop your head respectfully and hide your smile behind your hand.

* * *

The pregnancy was well-advanced when Little Wife discovered you, bent over the orchids in the garden. There was no longer any question of the pre-arranged marriage to the not-so-attractive second son of a government official. No chance to explain yourself. You were lost. From the moment your treachery was revealed not another syllable was spoken in your presence. An hour later, you left your father's villa carrying only your shame. At the window, your half-sisters turned away. First Wife's irises bowed their heads. Flies buzzed in the drains. On the narrow street, the boy charged with guarding your father's shiny green motorcar did not raise his eyes.

* * *

You walked, beside the gutters which carried the filth down the hillside to the grey waters of the harbour. Your toes ached in your satin house slippers as you travelled the length of the dragon's spine and along its mighty tail, while the dragon chuckled at your tiny footsteps massaging its back and tickling its ribs.

So imperceptible, he could barely feel them.

Perched on your shoulders, enjoying the show, the ghosts tugged at your hair, twisting it around their fingers into limp, damp tendrils, all the while hissing gleefully; they had always known it would come to this, had always known, always known, always known… Inside you, the child kicked and gasped for space beneath your breastbone. Queasy with freedom, you gazed at the greasy water of the harbour. A lettuce leaf floated by, buoyed by the current. Do it, do it, the ghosts shrieked, their voices strident now. Do it! Even the dragon lifted its tail, sending the foul water surging over your slippers.

on the water / a frangipani petal / dances with the moon

Your fingernails cutting half-moons into your palms, you turned and walked on, your feet wet and aching, and you realised with a pang why the skylark had not left its domed teak cage that day Little Wife had left the door open.

When you had walked the length of the Great Wall, when you were faint with walking, with the cruel taunt of the swirling ghosts, and the baby clamouring beneath your ribs, you sank to your knees on the greasy stoop of a darkened laundry, and, exhausted beyond death, you curled up on the concrete, the stoop stinking of urine and sweat and despair, and you let the steam vents warm you with their putrid breath while you slept.

* * *

The laundry owner's wife was made of rice paper. She had scissor-slit eyes and sallow yellow skin. You cringed and braced your bones, waiting for the kick that did not come. Instead, Rice Paper offered you a bowl of congee. She made no mention of your puffy eyes and bulging belly, but she put you to work in the laundry, repairing shirts and blouses and taking up hems. So, with your back bent, you paid your debt, breathing in the sweaty air, your eyes squinting into the future as you plied your needle. At night, you slept in the laundry's humid basement on a mattress shared with a girl from the provinces, and a few months later the two of you squeezed over to share it with your daughter, who was as beautiful and perfect as a button.

with dawn's breath / a tiny piece of heart

For two years, you stitched a life from scraps left in the laundry. Back then, you and your baby lived between the stacks of fresh towels, Button's glossy hair flashing black against white, black against white, as she tumbled and toddled through the days. You taught her to count, sing, and laugh, hushing her giggles whenever the laundry owner's wife was busy with a customer. Hushing your own giggles when they threatened to spill over the counter and into the street.

In these patchwork years, the ghosts were strangely quiet. Perhaps because Button was such a good child. You'd like to think that, wouldn't you? Yes, you'd like to think that. Perhaps, the ghosts were quiet only because the drone of the vents, the slosh of the tubs, and the hiss of the steam drowned out their voices. The pustules that bloated your belly had quietened too, although it's likely some of the tumours were expelled with the afterbirth, the slimy globules sluiced down the drain with a batch of grey laundry water. Whatever the reason, you revelled in the breathing space, that deceitfully simmering lull, because for a time you forgot those things you'd known before you were born; those things you'd learned in the rhythm of your mother's heartbeat and in the echoes of her sighs.

mountains / slumbering / in the bay

When the colony's water supplies were rationed, you put your mending aside, locking the baby in a storage cupboard while you carried a bucket back and forth between the laundry and the municipal tap. But outside the basket-bustle of the laundry, the ghost-voices returned, gusting in on the hot zephyrs that soared down the hillside and across the harbour. Standing sweltering in the queue, you longed for the quiet-simmer of the laundry. But while you were waiting, your fingers cramped around the handle of the bucket, ghosts whining in your ears, and your blood-humours bubbling, you spied a tiny white dogwood flower, its stem half-white and spindly, forcing crookedly through a crack in the concrete, and you realised you wanted more for your daughter than life in a cupboard, more than days on days spent squeezed between the stacks of white towels. So, the next day, when your buckets were full, you gave a coin to the girl from the provinces, asking her to mind Button for you, and, wearing clothes a wealthy client had forgotten to collect, you walked two blocks to the matchmaker.