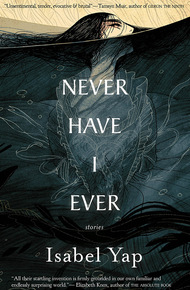

Isabel Yap writes fiction and poetry, works in the tech industry, and drinks tea. Born and raised in Manila, she has lived in the US since 2010. She holds a BS in Marketing from Santa Clara University and an MBA from Harvard Business School. Her debut collection, Never Have I Ever, received the British Fantasy Award for Best Collection. Her work has been a finalist for the Ignyte, Locus, Crawford, and World Fantasy Awards, and has appeared in venues including Lithub and Year's Best Weird Fiction. Her website is isabelyap.com.

Spells and stories, urban legends and immigrant tales: the magic in Isabel Yap's debut collection jumps right off the page, from the friendship and fear building in "A Canticle for Lost Girls" to the joy in "A Spell for Foolish Hearts" to the terrifying tension of the urban legend "Have You Heard the One About Anamaria Marquez." Never Have I Ever won the British Fantasy and Ladies of Horror awards, was selected for as a NYPL Best Book for Adults, and was a finalist for the World Fantasy Award.

Isabel Yap's debut, Never Have I Ever, full of "extraordinary, strange tales" (Booklist), landed on the World Fantasy Award shortlist and won the British Fantasy Award. Rich with urban legends and Filipino folklore, spanning many genres, from science fiction to straight up horror to paranormal romance, this amazing book from a fresh, gifted voice belongs in your digital bookshelf. – Mike Allen

"Where Yap consistently dazzles is her unsentimental, tender, evocative and brutal examination of the life and interiority of young women and girls: the innate monstrousness of growing up in the shoes marked 'woman'. A masterclass collection."

– Tamsyn Muir, author of Gideon the Ninth"An outstanding collection. . . . Yap's stories come at readers with the straightforwardness of a real conversation, which is a testament to the author's storytelling skills. However, once they get going, they always peel off a few layers to reveal something incredible—or incredibly dark, mysterious, or strange."

– Gabino Iglasias, Nightfire"Overflows with life and magic, and if you are not familiar with the vibrant literary scene in the Philippines, let this serve as a worthy introduction."

– Washington PostHave You Heard the One About Anamaria Marquez? (excerpt)

Isabel Yap

It all started when Ms. Salinas told us about her third eye. It was home ec., and we were sitting in front of the sewing machines with table runners that we were going to make our moms or yayas do for us anyway. I was pretty anxious about that project. I knew Mom was going to tell me to do it myself, because she believed in the integrity of homework. "Mica," Mom would say. "Jesus expects you to be honest, and so do I." I was wondering how to get Ya Fely to do it for me behind Mom's back when Ms. Salinas started blabbing about the ghost on the bus.

"You see, girls, most ghosts are very polite. At first I didn't even notice he was a ghost, and then I realized the woman sitting next to him couldn't see him, because she looked at me with this suplada face and said, 'Miss, are you not going to sit down?' Then the ghost shrugged, like, it's okay with me. So I had to sit on its lap, while at the same time sitting on the bus seat, and that felt so . . . weird."

Ms. Salinas was young and super skinny, which made up for her ducklike face. On the scale of teachers she was neither bad nor good. She liked to wear white pants, and a rumor had recently spread about how she liked to wear lime-green thongs and was therefore slutty. We amused ourselves during home ec. trying to look through her white pants every time she turned, crouched, or bent.

"Miss S!" Estella piped up. By then we had realized that if we kept her occupied, she might forget to give us our assignment. "When did you open your third eye?"

"I was born with mine open," she said. "My dad had it, and so did my Lolo. Oh, but my Kuya had to open his. He just forced it open one day by meditating. It's really easy as long as you know where yours is." A snicker from somewhere in the back made her look at the clock. "Girls, don't stop sewing."

We obediently hopped to work. I stepped on my machine's presser foot and stitched random lines through my table runner. Someone tugged on my elbow. "Help," Hazel whispered. She gestured at her machine: the cloth was bunched up in the feed dog, the needle stabbing through it at random points. I reached over and jerked one end of the cloth until it came unstuck. It was now full of micro-holes. She made a face. I smirked.

"You trying to give your cloth a third eye?" I asked.

• • • •

Anamaria Marquez was a student at St. Brebeuf's, just like us. One day she stayed after school to finish a project. At that time the gardener was a creepy manong, and when he saw her staying in the classroom all by herself he raped her. Then, because he did not want anyone to know about his crime, he killed her and hid her body in the hollow of the biggest rubber tree in the Black Garden. Nobody found out what had happened to her until after the manong died, when finally a storm knocked over the rubber tree—that was years ago, it's grown back now, duh—and the police found her bones.

If you look at the roots of the tree at night you might see Anamaria's face, or some parts of her naked body. If you stand in the Black Garden and stay absolutely silent you will hear her crying and calling for help.

But you shouldn't go near, because if you do she will have her revenge and she will kill you.

• • • •

It was fifth grade, a weird time when we were all changing. It seemed like every week someone was getting a bloodstain on her skirt, and sobbing in the bathroom from shame and hormones, while her barkada surrounded her vigilantly.

At the start of the semester we had a mandatory talk called You and Your Body! We were given little booklets with "chic" illustrations, diagrams of the female reproductive system, and free sanitary napkins. We spent a lot of our time vandalizing the chic illustrations. Lea found an ingenious way to turn a uterus into a ram by shading in the fallopian tubes, and we took turns drawing uterus-rams in each other's notebooks.

I held a slight disgust for all of this girl stuff, though I couldn't explain why. Maybe it was because I only had brothers, and some of their that-is-GROSS attitude rubbed off on me. My skin crawled whenever Mom or Ya Fely or the homeroom teacher made some reference like, "You are now a young lady. You are developing."

Our barkada had decided that we would tell each other "when we got ours," and that would be it, no hysterics or anything. I was more afraid that someone was going to get a boyfriend. Bea, the class rep, took every chance she could to tell people about her darling Paolo from San Beda. I was fine with Bea having a boy, and Bea was my friend too, but she wasn't part of our group. If any of us got a boy, I knew the dynamic would change so much we'd be screwed.

It was around this time, after all, that people's barkadas were getting shifted around, and that scared me more than I liked to admit. I loved my friends and wanted us to stay the same forever. There were four of us: me, Cella, Lea, and Hazel. Hazel and I were both in section C this year; Cella was in B, and Lea was in D. We had all ended up at the same assigned lunch table in first grade, and had continued eating lunch together since. We had our fights and silent periods and teary reconciliations, like everyone else, but otherwise we were one of the tightest groups around. These girls were the sisters I'd never had, and I thought we'd forgive each other anything.

So when Hazel told me she had opened her third eye, I laughed in her face and thought nothing of it.