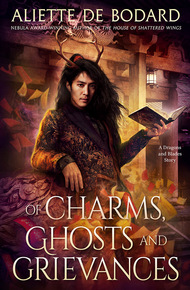

Aliette de Bodard writes speculative fiction: she has won three Nebula Awards, an Ignyte Award, a Locus Award and six British Science Fiction Association Awards. She is the author of A Fire Born of Exile, a sapphic Count of Monte Cristo in space (Gollancz/JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc., 2023), and of Of Charms, Ghosts and Grievances (JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc, 2022 BSFA Award winner), a fantasy of manners and murders set in an alternate 19th Century Vietnamese court. She lives in Paris.

2022 BSFA Award Winner for OF CHARMS, GHOSTS AND GRIEVANCES

2022 BSFA Award finalist for THE RED SCHOLAR’S WAKE

2022 Locus Award finalist for THE RED SCHOLAR’S WAKE

Winner of the 2022 British Science Fiction Association for Best Short Fiction

Finalist for the 2023 Locus Award for Best Novella

From the author of the critically acclaimed Dominion of the Fallen trilogy comes a sparkling new romantic adventure full of kissing, sarcasm and stabbing.

It was supposed to be a holiday, with nothing more challenging than babysitting, navigating familial politics and arguing about the proper way to brew tea.

But when dragon prince Thuan and his ruthless husband Asmodeus find a corpse in a ruined shrine and a hungry ghost who is the only witness to the crime, their holiday goes from restful to high-pressure. Someone is trying to silence the ghost and everyone involved. Asmodeus wants revenge for the murder; Thuan would like everyone, including Asmodeus, to stay alive.

Chased by bloodthirsty paper charms and struggling to protect their family, Thuan and Asmodeus are going to need all the allies they can—and, as the cracks in their relationship widen, they'll have to face the scariest challenge of all: how to bring together their two vastly different ideas of their future…

A heartwarming standalone book set in a world of dark intrigue.

A Note on Chronology

Spinning off from the Dominion of the Fallen series, which features political intrigue in Gothic devastated Paris, this book stands alone, but chronologically follows The House of Sundering Flames. It's High Gothic meets C-drama in a Vietnamese inspired world–perfect for fans of Mo Xiang Tong Xiu's Heaven Official's Blessing, KJ Charles, and Roshani Chokshi's The Gilded Wolves.

I love Aliette's books, and it's always a privilege – and pleasure! – to include one in these bundles – so come along on this award-winning, dragon-charming romantic adventure! – Lavie Tidhar

"A darkly delicious romp full of ghosts, murder, dragons, and romance, with a couple that just keeps getting better and better as they push each other to new limits."

– Stephanie Burgis, author of Snowspelled and Scales and Sensibility"Beautifully described, deeply caring, and satisfyingly murderous, it's an immersive delight."

– KJ Charles, author of the Will Darling AdventuresUp until Asmodeus spoke up, it had been an uneventful day — or, at any rate, not more eventful than usual. Thuan was visiting his family: the dynasty of shape-changing dragons that ruled the underwater kingdom of the Seine, among whom was his Second Aunt, the empress of the kingdom, and his many cousins. He and his Fallen angel husband Asmodeus had come down from the ruins of Paris, taking a much-needed break from Hawthorn, the House they jointly ruled. It was a holiday for both of them: Thuan didn't miss the committees, or the intrigues among the various magical factions within the House — or worse, the state dinners with other Fallen angels, very few of whom he actually appreciated.

Thuan's cousin had asked him to mind the children — an offer Thuan had said yes to, because the next person on his cousin's list had been Thuan's husband Asmodeus, and the words "Asmodeus" and "babysitting" in the same sentence were properly blood-curdling. Anything involving Asmodeus and patience and gentleness and diplomacy, in fact. It wasn't that he didn't understand children: it was just that his idea of age-appropriate included lectures on stab-wounds and detailed explanations on how to terrorize other children to do one's bidding. Thuan was absolutely sure none of his aunties would approve. Worse, they would pointedly remind him at every single family occasion that he was the eldest in the couple and should provide his husband with a good example.

Thuan cleaned up a lot of Asmodeus's messes, and he didn't need extras.

So Thuan took the children to a deserted area at the back of the citadel, on the edge of the forest of kelp that sheltered the imperial hunting lodge, and watched them play. They ranged from about nine to three years old, and all knew each other; and Ai Nhi and Camille, Thuan and Asmodeus's nieces — who had come from Hawthorn, so that their parents could have a break — were busy bossing all of them around with an ease which suggested they'd been practicing.

It was a quiet, beautiful day: over them was the sun of the dragon kingdom, a distant rippling orb, as if seen through water and from a great distance. The kingdom was underwater, its denizens water spirits, but it existed in a bubble of its own where magic kept everyone breathing and anchored to the riverbed: the children were kicking up clouds of silt as they ran, and the huge stalks of varech bent in what might have been a current, or what might have been an invisible wind.

Asmodeus had come along: he'd spent the first half of the morning sharpening an impressive array of knives that he'd managed to secrete in his swallowtail suit. Thuan had had to shepherd the children away, because Asmodeus looked quite ready to give a lecture and a demonstration. Now Asmodeus was reading a book, lounging on a rock. He'd shrugged off his jacket, and the crisp white of his shirt shone in the wavering sunlight. His entire being appeared limned with light: the black hair with a touch of grey at the temples, which Thuan ached to run his fingers through; the rectangular tortoiseshell glasses he wore over grey-green eyes, an affectation since like all Fallen, he had perfect eyesight; his long, delicate fingers and the white gloves he always wore outside. His face was sharp, focused on his book — another of the Gothic romances he enjoyed, especially when he got to complain about the characters' surplus of scruples or lack of intelligence.

He'd offered to help and Thuan had emphatically shot that down, and Asmodeus's only answer had been a sharp, ironic smile. By evening Thuan would be worn out, and they both knew it — and Asmodeus would be sure to offer sex Thuan wouldn't even have the energy for, and to regretfully downgrade it to cuddles and tea and steamed buns. Bastard.

Thuan was focused on the three children racing each other at the edge of the group — the other four were playing shells, with Camille gleefully snatching all the ones she'd won and holding them in a chubby death-grip. The first three were a little too close to a clump of giant kelp, which meant he'd lose them if he didn't pay attention.

"Thuan," Asmodeus said. His voice was quiet, matter of fact. It was that, more than anything else, which made Thuan look up with his heart in his throat — the very idea that something was serious enough that his husband wouldn't have any sarcasm for it.

"What?"

"You have one extra child among your charges."

"I—" Thuan stopped. He stared. Things kept blurring and seizing — which in itself should have been a clue, because six children shouldn't have been that hard to tell apart. "I count six."

"No, seven. The last one is a ghost."

"Uh." Thuan stared, hard, at the seventh child, transparent and faded — they kept weaving their way between the six others, blurring between their bodies. He couldn't make out the last child's face, or their clothes, or anything, and ghosts were a serious matter. He looked for threads of khi-water, the natural magic of the dragon kingdom — could he weave a peachwood sword or a drum and a gong with it? How did he warn the other children to get away from the ghost without warning the ghost?

And saw, to his horror, Asmodeus walk straight up to the ghost child, kneeling to be at their level with not a care in the world. "Hello there. What's your name?"

The child stopped blurring. The temperature in the air plummeted. Asmodeus gestured for the other children to shelter behind him — which they all did, except Camille, who stuck to Asmodeus's leg with the ease of long practice. Asmodeus, with equally long practice, peeled her off, and gestured for her to join the others: Camille pouted with an "Unka" which died on her lips when she saw his face, and dove behind his back.

The ghost was a girl, perhaps seven or eight years of age, the same age as Ai Nhi. She had a topknot and ill-fitting clothes — not linen ones, but folded and creased paper ones, and the smell of ashes clung to her. Her eyes were silver, the light in them shimmering like molten metal.

Her mouth moved. Her lips stretched, jaw yawning wider than any human one should have done. Her teeth were white, with a network of yellowed cracks, like old celadon but without any of the fragile beauty. What came out was a thin, reedy whisper like a dying man's gasp. Asmodeus didn't flinch, but Thuan didn't like the expression on his face: it suggested he was seconds away from stabbing someone — though it wouldn't be the child. Asmodeus treated children with a mixture of fascination and extreme protectiveness.

Blood blossomed from some invisible wound in the chest, staining the clothes. Asmodeus opened his mouth, but Thuan got there first. "Show me," he said.

The child shrugged. She held out a red-stained hand — blood dripped, slow and steady, to the ground. Ancestors, watch over me, Thuan thought, as he grabbed it.

It was cold, but not unpleasant. The blood didn't seem to touch or stain him, and she led him, gently but firmly, out of the patch of kelp forest Ai Nhi and the other children had been playing with, and into its deeper and darker areas. Behind him, only silence, and over him, shadow; the child's feet made no noise. Thuan's hackles rose, the antlers of his dragon form shimmering into existence on his temples, just below his topknot. He didn't take on his full dragon form — the long, serpentine body with stubby arms and clawed hands, and a flowing mane in addition to the antlers — because it was too large, and Heaven only knew where he was headed and how narrow it would be. But all the same, he was wary.

The child led him to a dilapidated courtyard in a ruined complex, with huge swathes of kelp growing over scattered rocks. Thuan thought, at first, that it was a temple complex, but he soon saw that it was the ruins of something much smaller: there was only one courtyard, and no tower or large shrine. Three buildings clustered around the courtyard: unusually, not pavilions with a covered gallery and pillars at the entrance, but squat ones with rectangular doorways at the top of short flights of stairs, and no flaring roofs. Everything was covered in a thin layer of the mould that was omnipresent within the dragon kingdom, a testament to the general decay both above and under the Seine.

The ghost led him, unerringly, towards one of the buildings: a large shrine with a defaced statue of a woman. She had a soft, narrow face that must have been quite beautiful once, before robbers got into the shrine: the eyes had been gouged out and the cheeks dug into, and her hands were broken off at the wrists. Scattered offerings lay in front of her: in spite of the state of its central statue, the shrine was obviously still frequented, with incense still being burnt and fruit being laid out. There was something... haphazard about the offerings.

Too few of them, that was the issue. It was a single person bringing these, and no one else, which meant few worshippers. An isolated shrine with a functionally dying cult.

The child stopped somewhere to the left of the statue, in the shadow of its left arm. She stood, jaw still yawning impossibly wide, and pointed. "Here?" Thuan asked.

The child said nothing. She was wavering, as if in a great wind, the contours of her face blurring. Thuan walked forward, and felt something crunch under his feet.

Bones.

They were small, and scattered, and unmistakably human. Thuan knelt, raising a cloud of dust, and stared at them, trying to collect his thoughts. He wove strands of khi-water, letting it tremble over the floor — his spell lit up, one by one, each of the scattered bones, a host of small islands of icy blue shivering in the darkness.

"That's a lot of bones."

Thuan hadn't heard Asmodeus come in. "The children!" he said.

"At the door," Asmodeus said. "I told them not to come in unless they wanted me to get very cross with them." They were clustering, uncertainly, in the door frame — Ai Nhi was holding them back, speaking urgently about Unka Asmo and how he always knew best. Trust his niece to never shut up, even in situations like these. "What do you have?"

"These," Thuan said. He gestured towards the floor. "You said there were a lot of them."

"Hmmm," Asmodeus knelt. A whiff of his perfume — bergamot and orange blossom — wafted up to Thuan. Asmodeus looked up, briefly, at the ghost, and then back at the bones. "Just very scattered. They're hers. The build matches, and I don't see extra ones. How did you die?" he said, to the child.

The child was cocking her head, as if pondering what to say.

"Asmodeus! That's hardly appropriate."

"She's dead," Asmodeus said. "And she just led you to her corpse. Don't be sentimental. Ghosts who stick around have unfinished business, do they not?"

"She could simply want a proper funeral," Thuan said.

Asmodeus's magic was trembling on the skeleton, a faint shimmering glow of Fallen radiance: a spell of reconstruction to tell him how she'd died. His face was grave, his gaze moving over the scattered bones. "There's no trace of violence. No fractured bones, no blood, and no weapon." He frowned, as the magic picked out a rib, then another. "She was slight, and the bones are too fragile. Malnourished. Very malnourished."

Thuan opened his mouth, closed it. "She died of hunger?"

"I think so." The anger in Asmodeus's face was visible. "Crawled here to seek refuge, to beg the protection of the immortal."

"How long ago?" The ghost was watching them, her face unreadable. She didn't look sad or angry, but then she wasn't human anymore.

"Fifty, sixty years ago? At least." Asmodeus made a stabbing gesture, and the magic snuffed itself out. "She looks like a wandering beggar. A hungry and desperate child, in the wide and wondrous dragon capital. I would guess an orphan. She wouldn't have ended up here, in such an isolated shrine, if she'd had parents or anyone watching over her." His face was stretched in that familiar smile: irony that barely masked anger.

Thuan didn't react. Truth be told, Asmodeus had a point. No one should die of hunger, and that it had happened this close to the palace was an abomination. "Do you think she wants revenge on those who neglected her? Sounds like all of them would be dead at that point." Thuan was half-minded to go have a word with them, possibly with an entire squad of imperial soldiers to get the point across.

"She doesn't feel angry to me," Asmodeus said. "Still hungry in death, perhaps?"

"She doesn't look like a hungry ghost."

Asmodeus raised an eyebrow. "How can you tell?" And, to the child, "Are you hungry? For food? For blood? For something else?"

The child yawned, displaying those cracked teeth — her lips moved, shaping a word. She seemed to have realised neither of them could hear it, for she shook her head instead.

Since Asmodeus didn't have any knowledge of dragon kingdom ghosts, Thuan felt obliged to say, "Hungry ghosts look more unkempt. Or pulling out people's entrails and eating them, depending on how bad the hunger gets."

Asmodeus didn't look impressed, but then he'd seen worse. And done worse, quite likely. Thuan got in the next question before his husband could lead them astray. "Do you want a proper funeral?"

The child keened, a piercing sound that sent Thuan to the stone floor. She was still frantically shaking her head — clearly he'd said something wrong. "I'm sorry I maligned you—" Thuan started, ignoring Asmodeus's sarcastic smile — his husband hadn't moved, and didn't look to be bothered by the keening at all — the child screamed again, cutting him off. She squared her shoulders, finally, and pointed.

There was a single bone in a corner of the room, which looked to be a rib. Thuan wasn't an expert in bones or in bodies — he didn't have Asmodeus's casual familiarity with hurting people, thank Heaven, but there didn't seem to be anything special about the bone —

Oh.

"Wait," he said, and walked across the dusty floor, towards the darkened area. There were no other bones, which meant everything was dark. Which meant that they'd missed the obvious.

There was another corpse.

This one wasn't just bones, and there was no question they had not died a natural death. For one thing, there was too much blood.

"There's no smell," Asmodeus said. He knelt by the corpse's side, looking briefly back at the statue of the shrine. "Of blood, or of decay."

"No," Thuan said. Both he and Asmodeus had a fine sense of smell, especially for things like this. "I think it's the ghost. Or the magic in the place. Or both." Everything was saturated with khi-currents of water, the usual magic of the dragon kingdom and the one that Thuan wielded, like most dragons. But there was a weave on top of everything else, some kind of preservation spell — probably something to keep the offerings safe.

"Or something else," Asmodeus said.

The ghost was kneeling on Asmodeus's other side. She smiled, showing those very creepy teeth again. She looked almost... satisfied? "I'm going to make inquiries about a monk when we get back," Thuan said. "There's got to be a way we can talk to her that doesn't involve guessing."

"Mmm." Asmodeus was lifting the corpse's blood-soaked clothes. "Come here, will you?"

"What is it?" Thuan said. Up close, the corpse looked oddly inanimate: the face pale, the limbs shrunken.

"You're the expert in kingdom people. And clothes. All I can tell is that she was a fish of some kind." Fallen magic glimmered on Asmodeus's hands: he was casting another spell of reconstruction. "And that she died two days ago. Blade driven into her, a couple times: the first one went through a couple major organs and would have eventually killed her, but the second one sliced the jugular. She bled out quickly. I can't find the blade, but it was something sharp, and very thin." He looked, speculatively, at Thuan's face, and reached out to touch Thuan's topknot. "Like a slightly larger hairpin."

Thuan shook himself free. "I'm not a walking demonstration for your deductions."

"Shame." Asmodeus smiled. "I take it everyone wears hairpins here."

Thuan nodded, briskly. "All officials, and most concubines, too. Unbound hair is... mmm. Too wild."

"Ah. I did think it was going to have different connotations here than rakishly Bohemian." Asmodeus looked thoughtful. Thuan was afraid of asking what he was pondering.

Thuan peered at the corpse, for a while. "Low rank official," he said, finally. "Blowfish — look at the spines on her cheeks. These would have puffed up when she were angry." The spines in question now looked like drooping plants. "She has a patch of rank, but it's blank. A clerk in one of the outer offices, perhaps? It would explain why she was out here." He frowned. Come to think of here, why was she here at all? The shrine was deserted. "What do you want?" he asked the child. "A proper funeral for her?"

A hesitant shake of her head, followed by a yes. So a funeral, but not the only thing.

"Revenge," Asmodeus said, sharply and bleakly. "Someone killed that woman. In front of you?"

The child nodded, twice — one for each question. Her face was grave. Thuan couldn't really read the expression on it: too much remove from him, and her features subtly wavered. "Look," he said, "There are protocols and people. We really shouldn't—" but Asmodeus cut him off.

"We'll look into it. You have my word."

He was bored again, and wanted something to keep him busy in the middle of citadel politics — and fewer things kept him busier than vengeance. Or perhaps he was simply angry, because he had once been leader of the Court of Birth, responsible for the safety of all of House Hawthorn's children, and old habits died hard. Thuan wasn't sure which. "We need to talk about this," he said.

A shrug, from Asmodeus. "Not here." He was standing up, brushing his hands. "I've seen all I need to see. Have a look, and then we'll leave."

"Asmodeus—" Thuan stared at the ghost, who stared levelly at him — and then at the doorway, where the children were still clustering. "I see. The children. You're not usually so considerate."

"There's too much unknown in this place," Asmodeus said. He was on edge, then, and no wonder. He always was, when going into the dragon kingdom. It was Thuan's family home, but not a place where he held any power or influence — and in Asmodeus's world, power, and the threats it allowed him to make, was what underpinned everything. "I want them back in the citadel."

Asmodeus headed, purposefully, towards the children clustered in the doorway. Ai Nhi, detaching herself from the group, ran towards him, and stopped. She wanted a hug, and was well aware she probably wouldn't get one: Asmodeus didn't really do affection that way. Asmodeus made a gesture Thuan couldn't see, and Ai Nhi buried his face against his chest. The other children clustered around him, vying for attention.

All right, very much on edge then.

And then, Thuan realised with dawning horror that among the children was the ghost. He hadn't seen her move. "Asmodeus!" he said.

Asmodeus looked down, at the ghost child. An expansive shrug. "We did need to bring her too, didn't we? She's a material witness."

A ghost in the imperial citadel — how much paperwork and how many explanations and justifications would Thuan have to give to Second Aunt and to all his cousins; how many lectures would he get from concerned aunties to stop mingling with death as it was bad for him, with a sideways look that included Asmodeus in the death group. "We can't just bring a ghost with us!"

But Asmodeus had already walked off. Typical.