Ed Gorman is best known for his crime and mystery fiction. He wrote The Poker Club which is the basis for a film of the same name directed by Tim McCann.

He has written under many Pseudonyms including "E. J. Gorman" and "Daniel Ransom." He won a Spur Award for Best Short Fiction for his short story "The Face" in 1992. His fiction collection Cages was nominated for the 1995 Bram Stoker Award for Best Fiction Collection. His collection The Dark Fantastic was nominated for the same award in 2001. Gorman won the 1994 Anthony Award for Best Critical Work for The Fine Art of Murder and has been nominated for multiple Anthonys in short story categories.

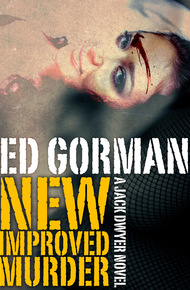

Jack Dwyer is a former cop who got the acting bug after he was cast in a local public safety commercial. He started acting lessons, quit his job, and applied for his private investigator's license (in very nearly that order). He also took a security guard job to keep the wolves away. The novel opens with Dwyer on a riverside park murder site. He was called there by a panicked former girlfriend. A girlfriend who left him for another man, and a girlfriend Dwyer isn't quite over.

The woman is nearly comatose when Dwyer arrives. She is distraught with grief and fear. The man who replaced Dwyer in her life is dead in the grass, and the gun that killed him is in her hand. The police arrive and everything fits neatly into a little package. No real investigation, other than into Jane Branigan—the girlfriend—and the case seems open and shut, but something about it bothers Dwyer. That something may be nothing more than his feelings for Jane, but Dwyer doesn't think she did it.

New, Improved Murder is a seriously good private eye novel. Jack Dwyer is a likable, compassionate, sometimes self-doubting reluctant good guy, who tends to stand on the outside. He is working class top to bottom, and the world through his eyes is a harsh, troubled place, with just enough hope and romanticism to keep him from the maudlin.

I first met Ed when I edited one of his books for publication. I fell in love with it in ten pages and made the publisher promise to let me edit all of Ed's books. His characters instantly become your best friends. New Improved Murder is one of the best and the fast pace will keep you flipping pages. – Patricia Lee Macomber

"Ed Gorman has the same infallible readability as writers like Lawrence Block, Max Allan Collins, Donald E. Westlake, Ed McBain, and John D. MacDonald."

– Jon Breen, Ellery Queen Magazine"One of the most original crime writers around."

– Kirkus"The modern master of the lean and mean thriller."

– The Rocky Mountain News"Intelligent characters uniquely motivated make for knock-out read."

– BooklistIt wasn't a park, really, just a strip of grass running along the river. In the summer it was a place for lovers, what with its picnic table and benches. Now, in November, with a steady, bitter wind slamming the gray water below into a jagged rock wall, it was home only for a few pigeons and stray dogs. Which was why the lovely blond woman in the tailored trench coat looked so out of place leaning against the rail above the river.

She showed no sign of recognition as I moved toward her, and I knew how bad a sign this was. Jane Branigan was almost neurotic about greeting you with deft little jokes and tiny, heartbreaking smiles. I should know. I lived with her for slightly longer than a year.

By the time I reached her, the noontime fog dampening my face, the chill deadening my fingers and knuckles, I saw that she held something in her left hand, something dangling just out of sight behind her coat. I shifted my steps slightly to the right to get a better look at what she was holding.

Jane Branigan held a .45 in her hand. Not the sort of thing you expected a woman who worked is a commercial artist, and who was the daughter of a prosperous trial lawyer, to have in her hand.

She didn't become aware of me until I was within three feet of her. Then she looked up and said, simply, "He's dead, Jack. He's dead."

From my years on the force it was easy enough to recognize that she was in shock. The patrician features, the almost eerie ice blue of the eyes were masklike. I was surprised that she even knew who I was.

"You'd better sit down," I said.

"Doesn't matter."

"Come on," I said. "It'll be better for you."

"He's dead."

"I'm sorry."

"The way he looked –"

My impression was that she was going to cry, which would have been better for her, but all she said was "Dead."

The .45 slipped from her fingers to the ground. I helped her to the park bench, sat her on the fog-slick surface. She was a statue, sitting there, poised, numbingly beautiful, as dead in her way as the man she mourned.

"Jane, can you hear me?"

Nothing.

"Jane, I have to ask you a few questions."

Nothing.

"Jane, where did you call me from?"

For now, anyway, it was no use.

I sat a moment longer staring at her, at her beauty that had turned my bed bitter and lonely, at her predicament, which rendered my old grudges selfish and embarrassing.

I sat there in silence, trying to think of what to say, what to do. Finally I had an idea. I touched her shoulder and said, "You remember the little puppy we almost bought that Christmas?"

Our first holiday together, shortly after we moved into our joint apartment, each of us in flight from terrible first marriages. We'd gone to the city pound and nearly taken a small collie home with us. Then we'd decided, sensibly enough, that because both of us had careers, and because we lived in an apartment, such confinement would not be fair to the dog. Still, from time to time, I remembered the pup's face, his wet black nose and the pink open mouth as we wiggled our fingers at him.

Apparently Jane had a reasonably clear memory of the dog too. She didn't smile or say anything specific, but something like a response shaped in her eyes as she stared at me. I took her lifeless hand, held it, saw in the slight tightening of her mouth and the tiny wrinkles around her eyes the stamp of late-thirties on her otherwise flawless face. I felt a little sorry for both of us. Our lives had not been exemplary and we'd hurt many people needlessly along the way. It had taken her hurting me before I understood that.

Then I got up and went over to the .45. I bent down, took out my handkerchief, and lifted the piece as carefully as possible. It was unremarkable, the sort of weapon sporting goods stores sell as nothing more than a way to get you to come back and buy ammunition. I looked at it in my hand and imagined a prosecutor pointing to it dramatically in the course of a trial.

Then I went up to the phone booth on the edge of the hill and called 911. It didn't take them long to arrive. It never does.

Edelman, shrewd man that he is, had learned enough from the dispatcher to bring an ambulance along. Two white-uniformed attendants had helped Jane into the rear of the vehicle and taken her away. They would take her to the closest hospital and the police would decide what to do from there.

Edelman had also brought along a big red thermos full of steaming coffee, which we shared as we stood at the railing overlooking the river.

"You aren't getting any younger, Dwyer," he said, smiling, taking note of my gray-flecked hair.

"At least I've got enough hair to turn gray." I smiled back. Martin Edelman stands six-two, looks as if he trains at Dunkin Donuts, and is sweet enough in disposition to make an unlikely cop, a profession he took up only because, as he once drunkenly confessed to me, he'd been called a sissy during early years. Now the kids who called him names were pencil-pushers and Edelman had earned the right to ask them with his eyes: Who was a sissy and who was not? Like many of us, Edelman spends his older years trying to compensate for the pain of his younger ones.

We stood silently for a time, blowing into the paper cups of coffee, watching a few straggling birds pumping against the dismal, sunless sky.

Then he said, "She's one of the most beautiful fucking women I've ever seen."

"Yeah."

"How do you know her?"

"She used to be a friend of mine."

"Friend. When we were growing up, friend usually meant somebody of the same sex, you know? I can't get used to the way that word is used today." He paused. "You mean you slept with her?"

"Yeah. We lived together for a year or so."

"This was after you left the force, I take it?"

"Uh-huh."

"You don't sound happy."

I stared out at the water. "I'm a little confused right now, Martin."

"The gun, you mean?"

"Confused about a lot of things. My feelings, mostly." He had been a good enough friend from my detective days that I didn't have much trouble talking to him. "I had all these plans for us, including marriage. She worked at an advertising agency and fell in love with a guy named Stephen Elliot there. She left me for him."

"A good Catholic boy like you should maybe think that God was paying you back for living in sin."

Both of us knew he was only half joking.

"It was a lot more than shacking up, Martin. A lot more. I really loved her."

"This Elliot, that's who we're checking on now, right?"

"Right."

I had explained to Edelman that I'd had no idea where Jane had called me from when she'd hysterically begged me to meet her here by the river. But what with the gun and all her "he's dead" references, I thought that the police should check Stephen Elliot's house, which they were doing now.

"Heartbroken, huh?" Edelman said.

"Yeah."

"That happened to me, just before I met Shirley. This little Polish girl. Goddamn, she was cute. She kept telling me how much she liked me and I took her real serious. I asked her if she'd marry me and she looked like I'd asked her if she'd get down on the ground and push dog turds around with her nose."

"Well, then you know what I was like for a year or so.

"Greatest diet in the world," Edelman said. "I dropped thirty pounds. My parents wanted me to stay heartbroken."

I laughed. He was good company, a good man.

He took a sip of coffee, then said, "You think maybe you made a mistake leaving the force?"

"Sure. Sometimes I do."

"I mean, the acting thing—"

He paused, trying to be delicate. With my ex-wife, my mother and father, and every single person I knew on the force, what I want to do with my life will always be "the acting thing"—something pretty abstract and crazy, as that phrase implies.

What happened was this: One of the local TV stations asked me to play a cop in a public service announcement about drunk drivers. Easy enough, since that's what I was, a cop. Then a talent agent called and asked me if I would be interested in other parts on a moonlighting basis, which I was. A year later I'd appeared in more than two dozen commercials and was taking acting classes from a fairly noteworthy former Broadway actor. Then my marriage started coming apart. I suppose I got obsessive about acting in front of a camera where I could put off the guilt and pain. I decided, against the advice of everybody I knew and to the total befuddlement of my captain, to give up the force and try to become a full-time actor, supporting myself in the meantime with a P.I.'s license and employment with a grocery store security company, busting shoplifters and trying to figure out which employees were stealing.

That was me, Jack Dwyer, thirty-seven, a man who'd become a bit of a joke. Maybe more than a bit, as certain smirks and eye-smiles sometimes conveyed.

"It's what I want to do with my life," I said, and I could hear the defensive tone sneaking into my voice. If I'm so damned sure that what I'm doing makes sense, then why do I always feel the need to defend myself? Only my fourteen-year-old son seems to understand even a bit of my motivation. He always gives me a sad, loving kind of encouragement.

"Yeah, sure, hell," Edelman said, afraid he'd hurt my feelings. "I wanted to be a surgeon at one time."

I laughed. "Maybe you should start cutting people up. You know, practice it a while, see if you like it. The way I did with acting at first."

"You're a crazy sonofabitch, Dwyer. A genuinely weird guy."

But I couldn't keep up the patter any longer. "She's probably in big trouble."

"Probably. Yeah."

A uniformed man came running down the hill from his patrol car, through the slushy dead grass and the wraiths of fog and the winter cold.

"Malachie called from this Elliot's house," the patrolman told Edelman breathlessly. "Said there's a body there and that the building manager has positively identified it as Elliot."

Edelman shook his head and put his big hand on my shoulder. "Looks like we've got some problems, my friend."