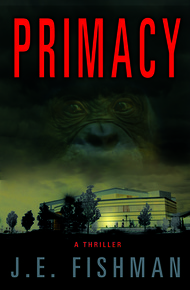

J.E. Fishman, a former Doubleday editor and literary agent, is author of the bestselling thrillers Primacy and The Dark Pool, the off-beat mystery Cadaver Blues, and the Bomb Squad NYC series of police thrillers: A Danger to Himself and Others, Death March, The Long Black Hand, Blast from the Past, and more to come. An occasional blogger for the Huffington Post, the Nervous Breakdown, and the Weeklings, he divides his time between Chadds Ford, PA, and New York City.

Researcher Liane Vinson thinks she can handle her promotion to the primate lab at Pentalon, the world's biggest and most secretive animal testing facility. But when Liane discovers that one of her favorite apes, a young bonobo called Bea, has shockingly developed the ability to speak, all her doubts awaken—doubts about right and wrong, about following the rules, and about sacrificing individuals to the supposedly greater good.

Soon, at risk of life and limb, Liane must challenge forces almost beyond her comprehension: a malevolent corporation, a venal federal government, an animal rights movement that's lost its way—and all of our assumptions about man's primacy in nature.

I've been a fan of J.E. Fishman since being introduced to his Bomb Squad NYC series. With Primacy, though, Fishman takes us into the world of animal testing, which you may or may not know is commonplace in many different industries. This book will have you questioning everything you think you understand about man's place in the evolutionary chain, while forcing you to hang onto the arms of your chair as you take a wild ride. – Allan Leverone

"Fishman is a deft, fluent writer who's great at turning out intricate action scenes, and he gives us appealing characters—even the chimp grows on you—to boot… More fun than a barrel of overgrown monkeys."

– Kirkus ReviewsAn "appealing debut thriller... Those with an interest in animal rights will be particularly enthralled."

– Publishers Weekly"A magnificent job… This debut novel is a marriage of medical thriller, along the lines of Robin Cook, to fear on a scale you have never experienced, as typically brought to readers by Michael Crichton."

– Suspense MagazineHe had the poet T.S. Eliot in mind as he felt for his weapon in the winter woods, Eliot who wrote about shadows falling between emotion and response, between essence and descent.

They crouched among shadows, two men in camouflage. The white and the black. The light and the dark. Above them, a tall chimney spewed smoke toward the low overcast.

A furnace in the kingdom of despair, he thought.

"Smell it," his partner, the black African, whispered.

It was sweet and sharp and carbon-saturated, the scent of something beyond death: of putrid flesh consumed.

The African held a pair of whitetail deer, halter-tamed, while the white man examined the chain link fence in the glow of a penlight. With a clip he attached the wire in his hand to a line woven through the fence at eye level, walked six feet, and clipped the same line with the other end of his wire. He repeated the procedure for the second line, which was near ground level. Exactly in the middle, he severed the fence vertically with spring-loaded bolt cutters.

Dit. Dit. Dit. Dit. Dit. Dit. Dit. Dit. Dit.

It gaped open.

"Pedza," he said. Done.

They retreated fifty yards with the deer in tow, sat on the ground and waited, leaning against cold tree trunks.

For an hour they didn't move. No one came.

They exchanged a silent nod and the white man stood with one lead shank in hand. His small doe, stirred from boredom, sensed something new and became skittish. He reassured her with a pat and directed her to the hole in the fence. When they were on top of it he straddled her and deftly unsnapped the halter, pushing her through with a smack on the hindquarters. She hustled into the darkness, kicking up dried leaves.

By the time motion detectors tripped the floodlights he had retreated into the shadows. From lawns to macadam, the grounds inside the fence looked like a moonscape under the glare of the lights, all color washed out to gradations of silver.

Two spotters appeared on the flat roof of the boxy industrial building. They scanned the property with binoculars. A third guard moved behind the glass doors of the newly illuminated front lobby. He had a pistol and a two-way radio. He tested the doors with a shove and looked out into the parking lot. There was nothing but the doe cantering across the lawn with its white tail raised. The guards exchanged a few words over the radio and withdrew to their original positions.

The men in the woods waited longer, undiscovered.

The floodlights powered down.

Half an hour later, the black man stood with his doe. He led her to the fence as the first man had, straddled her, unsnapped the halter, smacked her in the rear and received a kick in the knee. Grimacing but silent, he limped back into the shadows as the floodlights surged on again.

Once more the guards appeared on the roof and in the doorway. They registered the second doe, which cantered to its grazing mate. Over the radios, a longer exchange ensued, then noncommittal gestures, and the guards retired. When the floodlights snapped off again, the men in the woods waited for their eyes to adjust and traded knowing glances.

Fifteen minutes later, they stood poised at the gap in the fence with the deer a hundred yards to their right. They hugged the fence until they had an angle to the side door that would take them within twenty yards of the deer. They waited with a hand on each other's shoulder and surveyed the dim scene one last time. Then they bolted for the door as the floodlights buzzed to life again.

The deer skittered toward one another, alert. The guards were slower to appear. By the time they did, the intruders had flattened themselves against the reflective glass wall. The white man, using his partner for a ladder, quickly rose beside the plastic bubble that protected the camera by the door. He fixed a larger bubble over it with a hologram burned into the plastic — a replica of the real camera's view with no one at the door. He climbed down and they flattened themselves against the wall again, marking time.

Looking up, they saw the sleek barrel of a rifle extend over the roofline and steady.

"I should waste these damned deer." It was the voice attached to the rifle. "How many times are we gonna drag ourselves out here?"

"As many as it takes."

Radios barked.

"Fucking Christmas Eve, too, and all. Venison?" The rifle swung.

"Put it down, man. Discipline."

"These endless fence violations... They'll need another perimeter check in the morning."

The radios crackled once more, briefly. The footfall of the guards faded. A few minutes later, the lights powered down again.

With a small hand torch and his bolt cutters, the white man removed a push bar that held the door fast. Before allowing it to swing open, the African slipped a flat magnet where he knew the alarm contact would be.

The African produced a thick rubber exercise band, missing its handles. They raced up the hall. The lobby had wall panels of brushed stainless steel, gray marble tiles and indirect lighting. In one corner stood an artificial Christmas tree with a dozen wrapped presents piled beneath it. Music played in the background — Nat King Cole crooning "O Holy Night."

A single guard sat at the security desk, facing a panel of monitors. His hair looked greasy from behind. The intruders took him so quickly that he never left his chair and had no chance to unholster his sidearm. The African twisted the guard's gun arm behind his back and wrapped the rubber band around his neck. His partner held the sharp tip of a hawksbill blade to the point of the guard's nose, producing a bead of blood.

"Not one sound."

The guard tried to swallow, but the pressure of the rubber band constricted his Adam's apple. When he attempted to nod his head the knife dug into his nose. He blinked in terror.

They sealed his mouth with duct tape and fastened him to the chair. They took his passkey and rolled him into a nearby closet, closing the door. The African slipped the guard's pistol into his own belt.

The men had memorized the plan of the building. They headed straight for the ground-floor laboratories, which occupied the north side. They touched the guard's passkey to an electronic pad, and the door swung open.

Inside, a whiff of antiseptic mingled with the throat-constricting odor of animal excrement. Living things shifted and rustled in dark corners. As the lights flickered on, the sights and smells and sounds made the two men emotional. The African vomited into a biohazard bin. The white began to fling open cages, freeing rabbits and cats and dogs and monkeys. Some of the animals cowered in their enclosures, even with the doors open. Others lay listless. The two men sped up and down the lines of cages, unfastening every door. Monkeys screeched interminably. Two dogs circled, trailing catheters. A baboon, tied to the side of its cage, hugged itself with one untethered arm. It was covered in bloody bandages and open sores.

The white man paused before the baboon's pleading brown eyes.

"Sweet mercy is nobility's true badge," he quoted. He took out his suppressed 45-caliber Heckler & Koch and winced when the baboon's head exploded, blood and brains splattering the room. The bullet ricocheted off a steel countertop, and remnants of the baboon's skull vibrated the bars of the cage.

Several other animals, too debilitated to move, met the same fate while the African herded the remaining creatures out the door, down the hall, and into the open air.

"Dzikinuka," he instructed the walking wounded. Be free.

Back inside, an alarm sounded and the men's eyes met. The guards from the roof were certain to arrive shortly.

Each intruder replaced the magazine in his weapon.

There was no one in the hall and no sound other than the blaring alarm. They raced past the crematorium door, around a corner and into a room lined with filing cabinets. Sweating now, they threw open drawers and emptied folders onto the floor.

The white man sparked his torch into blue flame. He touched it to several piles of paper and smoke braided to the walls as the small fire slithered into an open blaze. A second alarm sounded and red exit signs began flashing.

"Bibinuka," he said. Get out.

The guards had the lobby flanked, their guns drawn. The intruders sprinted down a side hall, ignoring calls to halt. They flew through the original door, but the African was a step slow, limping.

"Rambauchiita!" he shouted. Go on!

His partner hesitated, extending a hand to assist.

The guards were gaining on them now.

"Rambauchiita! Rambauchiita!" the African pleaded.

Firearms snapped. Bullets ripped the air, and the African crumpled.

A dozen animals hobbled in the glare of the parking lot — dazed by unnatural brightness and unexpected freedom.

The white man weaved among them. As he reached the woods, a large explosion lit the night.