Kristine Kathryn Rusch writes in multiple genres. Her books have sold over 35 million copies worldwide. Her novels in The Fey series are among her most popular. Even though the first seven books wrap up nicely, the Fey's huge fanbase wanted more. They inspired her to return to the world of The Fey and explore the only culture that ever defeated The Fey. With the fan support from a highly successful Kickstarter, Rusch began the multivolume Qavnerian Protectorate saga, which blends steampunk with Fey magic to come up with something completely new.

Rusch has received acclaim worldwide. She has written under a pile of pen names, but most of her work appears as Kristine Kathryn Rusch. Her short fiction has appeared in over 25 best of the year collections. Her Kris Nelscott pen name has won or been nominated for most of the awards in the mystery genre, and her Kristine Grayson pen name became a bestseller in romance. Her science fiction novels set in the bestselling Diving Universe have won dozens of awards and are in development for a major TV show. She also writes the Retrieval Artist sf series and several major series that mostly appear as short fiction.

To find out more about her work, go to her website, kriswrites.com.

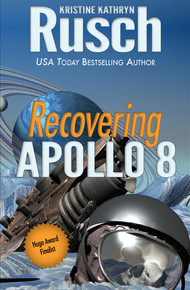

In a world where Apollo 8 veered tragically off course, the event sent the astronauts, and the space program, hurtling into space, lost and helpless. The tragedy so affected eight-year-old Richard Johansenn that he dedicates his life—and the fortune he amasses along the way—to recovering the capsule. But Richard's quest proves more complicated than a simple recovery mission, causing him to question the meaning of life, the meaning of death and the heroisms in between.

I had initially asked one other major author to join us in this bundle, but she couldn't free up an appropriate sf novel in time. I prefer to have ten books in a bundle, so I decided it was easier to add something of mine than miss the deadline or short the bundle. This award-winning novella has been reprinted all over the world. It seems to have touched a chord with readers everywhere. I hope you enjoy it as well. – Kristine Kathryn Rusch

"This is a thoughtful, introspective piece that speaks to themes of hope, doubt, perseverance, and obsession."

– Tangent Online"There is very little of this sort of science fiction published nowadays—the real thing, the exploration of Earth's solar system, without the slightest concession to the fantastic. Rusch celebrates the spirit of exploration, the adventure into the great unknown. … this tribute to humanity's first ventures into space is Recommended."

– The Internet Review of Science Fiction". . . this is one of the most exciting short story collections I've read in years, perhaps ever."

– SkyLightRain2007

RICHARD REMEMBERED IT wrong. He remembered it as if it were a painting, and he was observing it, instead of a living breathing memory that he had a part of.

The image was so vivid, in fact, that he had had it painted with the first of what would become obscene profits from his business, and placed the painting in his office—each version of his office, the latter ones growing so big that he had to find a special way to display the painting, a way to help it remain the center of his vision.

The false memory—and the painting—went like this.

He stands in his back yard. To his left, there is the swing set; to his right, clothes lines running forward like railroad tracks.

He is eight, small for his age, very blond, his features unformed. His face is turned toward the night sky, the Moon larger than it ever is. It illuminates his face like a halo from a medieval religious painting; its whiteness so vivid that it seems more alive than he does.

He, however, is not looking at the Moon. He is looking beyond it where a small cone-shaped ship heads toward the darkness. The ship is almost invisible, except for one edge that catches the Moon's reflected light. A shimmer comes off the ship, just enough to make it seem as if the ship is expending its last bit of energy in a desperate attempt to save itself, an attempt even he—at eight—knows will fail.

Someone once asked him why he had a painting about loss as the focus of his office.

He was stunned.

He did not think of the painting, or the memory for that matter, as something that represented loss.

Instead, it represented hope. That last, desperate attempt would not have happened without the hope that it might work.

That's what he used to say.

What he thought was that the hope resided in the boy, in his memory, and in his desire to change one of the most significant moments of his past.

***

The real memory was prosaic:

The kitchen was painted bright yellow and small, although it didn't seem small then. Behind his chair were the counters, cupboards and a deep sink with a small window above it, a window that overlooked the sidewalk to the garage. To his left, two more windows overlooked the large yard and the rest of the block. The stove was directly across from him. He always pictured his mother standing at it, even though she had a chair at the table as well. His father's chair was to his left, beneath the windows.

The radio sat on top of the refrigerator, which wasn't too far from the stove. But in the center of the room, to his right and almost behind him, was the television, which remained on constantly.

His father could read at the table, but Richard could not. His mother tried to converse with him, but by his late childhood, the gaps in their IQs had started to show.

She was a smart woman, but he was off the charts. His father, who could at least comprehend some of what his son was saying, remained silent in the face of his son's genius. Silent and proud. They shared a name: Richard J. Johansenn, the J. standing for Jacob, after the same man, the family patriarch, his father's father—the man who had come to this country with his parents at the age of eight, hoping for—and discovering—a better world.

That night, December 24, 1968, the house was decorated for Christmas. Pine boughs on the dining room table, Christmas cards in a sleigh on top of the living room's television set. Candles at the kitchen table, which his father complained about every time he opened his newspaper. The scent of pine, of candle wax, of cookies.

His mother baked her way to the holiday and beyond; it was a wonder, with all those sweets surrounding him, that he never became fat. That night, however, they would have a regular dinner since Christmas Eve was not their holiday; their celebration happened Christmas Day.

Yet he was excited. He loved the season—the food, the music, the lights against the dark night sky. Even the snow, something he usually abhorred, seemed beautiful. He would stand on its icy crust and look up, searching for constellations or just staring at the Moon herself, wondering how something like that could be so distant and so cold.

That night, his mother called him in for dinner. He had been staring at the Moon through the telescope that his father gave him for his eighth birthday in July. He'd hoped to see Apollo 8 on its way to the lunar orbit.

On its way to history.

Instead, he came inside and sat down to a roast beef (or meatloaf or corned beef and cabbage) dinner, turning his chair slightly so that he could see the television. Walter Cronkite—the epitome, Richard thought, of the reliable adult male—reported from Mission Control, looking serious and boyish at the same time.

Cronkite loved the adventure of space almost as much as Richard did. And Cronkite got to be as close to it as a man could and not be part of it.

What Richard didn't like were the simulated pictures. It was impossible to film Apollo 8 on its voyage, so some poor SOB drew images.

At the time, Richard, like the rest of the country, had focused on the LOS zone—the Loss Of Signal zone on the dark side of the Moon. If the astronauts reached that, they were part of the lunar orbit, sixty-nine miles from the lunar surface. But the great American unwashed wouldn't know they had succeeded until they came out of the LOS zone.

The LOS zone scared everyone. Even Richard's father, who rarely admitted being scared.

Richard's father, the high school math and science teacher, who sat down with his son on Saturday, December 21—the day Apollo 8 lifted off—and explained, as best he could, orbital mechanics. He showed Richard the equations, and tried to explain the risk the astronauts were taking.

One error in the math, one slight miscalculation—even if it were accidental—a wobble in the spacecraft's burn as it left Earth orbit, a miss of a few seconds—could send the astronauts on a wider orbit around the Moon, or a wider Earth orbit. Or, God forbid, a straight trajectory away from Earth, away from the Moon, and into the great unknown, never to return.

Richard's mother thought her husband was helping his son with homework. When she discovered his true purpose, she dragged him into their bedroom for one of their whisper fights.

What do you think you're doing? she asked. He's eight.

He needs to understand, his father said.

No, he doesn't, she said. He'll be frightened for days.

And if they miss? His father said. I'll have to explain it then.

Her voice had a tightness as she said, They won't miss.