Walter Jon Williams is an award-winning author who has been listed on the best-seller lists of the New York Times and the Times of London. He is the author of over forty volumes of fiction.

His first novel to attract serious public attention was Hardwired (1986), described by Roger Zelazny as "a tough, sleek juggernaut of a story, punctuated by strobe-light movements, coursing to the wail of jets and the twang of steel guitars." In 2001 he won a Nebula Award for his novelette, "Daddy's World," and won again in 2005 for "The Green Leopard Plague."

His fantasy novel Metropolitan was nominated for a Nebula Award for novel. Its sequel, City on Fire, was nominated for both a Nebula and a Hugo.

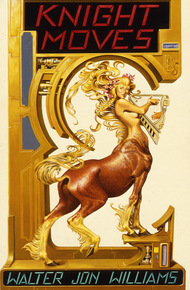

Eight hundred years ago Doran Falkner gave humanity the stars, and he now lives with his regrets on a depopulated Earth among tumbledown ruins and ancient dreams brought to life by modern technology.

But word now comes that alien life has been discovered on a distant world, life so strange and impossible that the revelation of its secrets could change everything. A disillusioned knight on the chessboard of the gods, Doran must confront his own lost promise, his lost love, and his lost humanity, to make the move that will revive the fortunes both of humans and aliens . . .

I first learned of Walter Jon Williams when he burst onto the publishing scene with his visionary magazine stories. Walter went on to write twenty-seven novels and three story collections, appear on the New York Times and London Times bestseller lists, win the Nebula, be nominated for the Hugo, Nebula, and World Fantasy Awards, and also write for comics, the screen, and for television. Walter brings his visionary style to Knight Moves, which takes us to a far-future Earth depopulated by a space-faring humanity, a lonely and fantastic place where legends roam again, thanks to modern technology. I welcome this classic science fiction to the Philip K. Dick Award Bundle. – Lisa Mason

"Knight Moves is an engrossing and evocative read, a tale of immortality and love and death rendered in a style that reminds me more than a little of the early Roger Zelazny. Williams' people are intriguing and sympathetic, and his portrait of an Earth left transformed and empty by a humanity gone to the stars, where aliens dig among ancient ruins for old comic books while the creatures of legends stir and walk again, will linger in my memory for a long time. Williams is a writer to watch, and– more importantly– to read."

– George R.R. Martin, author of Game of Thrones"Knight Moves uses an unmatched cast of characters, human and otherwise, to tell an intriguing story."

– Fred Saberhagen, author of the Book of Swords TrilogyProjected against the darkness of the polarized window was a plain, bathed in a harsh bright light that made the green of the grasslike stuff seem almost black. The sky was a blazing white. Strange flat-topped trees, like inverted cumulonimbi, stood on the horizon. It looked like an awful place to spend a weekend.

In the foreground moved a herd of lazy animals, bipedal, each with a long, snakelike balancing tail and questing, grasping forepaws. Despite a heavier head and eyes on stalks, they resembled nothing so much as large kangaroos, except when they walked, they did not hop but placed one foot in front of the other and could do so quickly if they wanted to. I'd been told they made bad eating. They were called lugs, named, I gathered, after a member of the initial survey team who rather resembled one.

"The ecology and the assumed evolutionary history of Amaterasu make little sense," said Dr. Nelda Li-Shing y Saavedra. She was a short, dark-haired, round-faced woman who lectured in peremptory tones that sounded disapproving.

Amaterasu, it seems, did not meet her standards. She sniffed and spoke on.

"The lugs are the largest animals on the planet," she reported. "Nothing else even comes close; there are small insect forms, burrowing creatures, fish in the seas and lakes. We have found nothing larger than one-tenth of the mass of the average lug, and that was a fish. All the other life forms on Amaterasu are at a fairly primitive stage of evolution. While any Earth analogue is bound to be imprecise, few of the planet's life forms exceed in complexity the earthly forms of the Devonian, although in variety they are not nearly as numerous, and they do not display the gigantism so prominent in Devonian aquatic life.

"There are no creatures that prey on the lugs— there aren't any big enough for that. So far as we can tell, there have never been any. There aren't any parasites either, not even intestinal parasites. The type of grass that covers the plains of the planet rarely exceeds a foot in height, even when at its most mature. So why develop fast-running, warm-blooded bipedal creatures with eyestalks, if there's no grass to have to peer over and no predators to run from?"

The lecture went on. The grasses were mossy and uniformly low to the ground in order to avoid being burned around noontime by Amaterasu's pulsing blue-white sun. The trees were not trees but sophisticated, cooperative colonies of moss; their branches and leaves were sun-reflecting rather than sun-absorbing; they created a shady spot underneath which the real work of photosynthesis went on without the danger of being seared by the sun. The lugs didn't make ecological sense from this perspective either; they were simply too large.

No wonder the place had never been colonized despite its proximity to Earth. The pioneering expedition had taken one look, filled out its report card, and fled in horror after naming the place after the Japanese sun goddess. Centuries later, a team intending to study the system's blue-white sun had brought word of the first anomalies.

Great, I thought. Hot, with horrible solar radiation, and boring.

"We have theories that attempt to explain some of the anomalies," Dr. Li-Shing continued. Her tone indicated that she disapproved of theories as well. "Perhaps other, larger life forms did evolve, including a carnivorous species preying on the lugs, and perhaps all these other forms were wiped out in some catastrophe— solar flares from the sun, possibly, or collision with a meteor several miles in diameter that would have thrown up enough debris to darken the planet for years. Possibly even some kind of plague. The theories seem incomplete. They don't explain how the lugs survived or why evolution and species differentiation seem so stunted even in environments that would be least affected by a catastrophe, such as the aquatic environment. However, the survey teams failed to find any evidence of a catastrophe, and there is no evidence of a large extinct species. The astronomers have concluded that the planet's sun entered a stable period many millions of years ago and that there is no evidence of its ever having deviated from its current pattern. And nothing we've come up with has ever explained this.'"

I leaned forward in my seat, paying close attention. After all these preliminaries I was at last going to witness what the fuss was really about.

A white cartoon-type circle appeared around one of the lugs in the mid-foreground, a bull's-eye calling attention to something that was going to happen. Then the circle was still there, but empty. The lug had vanished.

"On this particular occasion," Li-Shing went on, "the lug was instantaneously displaced approximately eight hundred kilometers to the westward. All the lugs in this herd were tagged with radio beacons; our computers picked up the anomaly at once and signaled us."

I watched more examples. Lugs vanished. On other, rarer occasions, when the recorders happened to be pointing in the right direction, they appeared out of nowhere. The movement seemed to be coexistent with the movement of a volume of air equivalent to that from which a lug vanished— since it did not leave a vacuum behind, which would have made a loud popping noise. Displacement was apparently random; no pattern had been observed. It was also instantaneous. The computers monitoring the tagged lugs registered no gap in time between one existence and another. The lugs took no time to move from one place to another, nor did they spend any time elsewhere; they simply moved.

Instantaneous, in this case, meant faster than light. Faster than a beam of light could have moved even had it traveled on a straight-line path through the planet's crust.

Dr. Li-Shing reported in an exasperated voice that no evolutionary reason for the existence of such a talent had ever been determined. No predators to escape from, you see. Team members had considered the possibility that the lugs were not native to the planet but had been deposited there at some time in the past by sentient beings.

There was no evidence for this theory either, although the stellar neighborhood was being scoured by robot craft in hopes of discovering the lugs' planet of origin. No word as yet from the robot probes.

She asked me if I had any questions. I didn't. None that she could answer anyway.

There followed a biologist who gave a report on lug anatomy. Nothing out of the ordinary for any grazing animal of that size. Multiple stomachs for the digestion of the tough foliage. Small brains, decidedly unintelligent. Certainly no organ discovered capable of producing the effect described. Any questions, Mr. Falkner? Thank you.

Her place was taken by an obese behaviorist named Innis. Lugs, he reported, had no social organization worth speaking of. They were herd animals, but since herd animals generally congregate to protect themselves from predators, and there were no predators on the planet, it was assumed that the lugs herded because they preferred one another's company to solitude.

Mating took place twice a year, mates choosing one another apparently at random. Gestation took about three-quarters of a year. Luglings were born fully developed and hungry, and within hours of their birth were generally walking and eating the same monotonous diet as their parents. The luglings hung about their mothers for a month or so, after which both lost interest and the little ones were on their own. Full maturation took place over a couple of years. Average life expectancy was about ten years. There were no checks on population save for fertility, which was fairly low. Satellite data estimated the total population to be about a billion. If those tagged were a representative sample, fifteen or twenty thousand could be expected to teleport in a given year.

The population was stable. Despite the lack of natural enemies the lug population was refusing to increase. Innis offered no explanation for this peculiar fact.

In a jolly, burbling voice, he then went on to describe various attempts to make the lugs teleport. Lugs had been captured and shut up in pens within sight of large amounts of food. Instead of teleporting, the lugs exhausted the food in their pens and then starved. Lugs had been shut up in utter blackness, with the hopes they would teleport away. They also had starved. Vast amounts of food had been presented to lugs who had successfully teleported, in the hopes this would be perceived as a reward and the lugs induced to teleport again. The lugs had eaten the food and stubbornly refused to make another jump.

If Innis were forced to make a guess, he said, he would guess that teleportation was not something that the lugs did but rather something that was done to them. But he would prefer not to have to guess until he saw further data.

He did not ask me for questions. I did not ask any.

Innis was followed by the recording of a middle-aged, kindly looking priest of the Ptolemaic Church of the Christ, a sect embracing respectable, sensible, moderately intelligent, non-excitable and usually very dull worshipers. After making a series of odd, tentative noises into the recording device in an effort to determine whether it had been switched on, the priest, with a slight stammer and a number of nervous twitches that showed his general inexperience with recorders, went on to explain, in an amazingly circumlocutive style, the possible theological import of what was being called the "lug phenomenon."

Since the dawn of the age of reason, he reported, believers, in order to confirm their intuitional faith, have been looking for objective proof of the existence of God. A true miracle has always been considered a manifestation of God's grace, but few miracles come ready-supplied with the sort of objective proof demanded by the intelligent skeptic.

The appearance of a creature which, for no conceivable reason, is able to teleport from one place to another about its planet, and which, after rigorous and scientific inquiry, is seen to be able to do so in abrupt contradiction to any known law of nature, might, Q.E.D., be considered objective proof of the existence of the Creator.

Amen. I yawned, reflecting that this was the first time I'd heard anyone say "Q.E.D." in many years. The priest smiled uncertainly, signaled to someone to turn off the recorder and did not ask for questions.

There were more recorded reports on minor topics. Blue-white stars. Detailed illustrations of lug cell structure. Last of all, a presentation by the physics team itself, concerning how it all might have been done. I felt a cold hand touch my neck. I didn't want this.

My three former students were introduced one by one. First was Muhammad al-Qatan, looking studious and grave in the blue collarless uniform, complete with medals, in which Kemp's dressed their professors. He was brilliant and one of the most stable, reliable people I knew— not quite self-effacing, but willing to sublimate his ego toward a goal if necessary. When his researches led to the discoveries of the chronograph, I'd had to fight to make sure he received proper credit. He'd been married to the same woman for two hundred years, ever since his undergraduate days, a record among people of my acquaintance. He looked odd without his mustache. He had apparently shaved it off fairly recently since he kept rubbing his upper lip as though expecting to find something there.

Next to him was Peirce Hourigan, his eyes grinning at me from beneath a shock of kinky hair. A radiant madman, half Irish, half Australian aborigine. I hadn't heard from him in years and was glad he'd survived his lunatic, impulsive attempts to scale, unaided, the exteriors of large buildings, to dive old-fashioned atmosphere craft under bridges, to set fire to colleagues' wastebaskets and sometimes their clothing. His lanky body was sprawled all over his chair, and perched on his shoulder he carried an enormous cockatoo, his uniform white with its droppings. It nibbled his ear and squawked from time to time. Leave it to Hourigan to figure out some way to subvert the dignity of a scientific conclave.

The recorder at last moved to Mary Liddell, and I realized I had been holding my breath. I expelled it as I saw the silver hair, the solemn gray eyes, the slight frown as she looked, businesslike, into the recorder and waited her cue. At first I thought McGivern had been wrong and she had changed her mind; but then she began to speak and I noticed the lines around her eyes and mouth, and when she raised a hand, I saw the thin boniness of it and the translucence of her skin, and I thought: She is dying. The silver hair will easily hide the gray.

She is the youngest of all, I realized. I felt my hands clench, nails scoring palms. She is the most brilliant of these three most brilliant students, and all of them were smarter than I had ever been... and she was killing herself. It was obscene.

I thought of space, of the indifferent and eternal brilliance and velvet blackness. The recording had taken almost twelve years to get here. If I gave in to McGivern's nonsense and went to Kemp's, how much older would she be when I saw her next? Ancient, I thought. Perhaps dead.

The recorder left her face and I breathed again. The presentation began, and great nonsense it was: It took a lot of time to say nothing. An instability, lasting for only a fraction of a picosecond, had been found in some of the higher-energy Zimmerman particles, and that might imply some peculiar interaction with other particles, possibly the long-theorized-but-never-discovered tachyon, but energies did not exist in sufficient quantity to create such particles if they did exist, or to track them when they were created. It was similar to the problems that existed with the chronograph, which could open a momentary, sideways portal through time, but only in a single direction. From our future we could view the past. We could even map it sufficiently to create an exact duplicate of Apollo's temple here in Delphi; but to actually insert a person or an object into the past— and thus to change the past— required a titanic consumption of energy, enough energy to alter the universe from that moment onward. And that energy, even with the use of the biggest Falkner generator ever built, was not available to us.

The presentation said nothing new. We'd known about the high-energy Zimmerman particles for years, but we had also known of the energy barrier. It was Mary who had the most sensible speech. Even if the lugs somehow had access to such energy, how could they control it? With the titanic expenditure of energy that we knew had to be necessary for a phenomenon such as teleportation, how did the lugs prevent leakage? At each event there should have been enough stray radiation to fry any organism nearer than the horizon, but there wasn't; so far as anyone could detect, there wasn't a single stray particle. The phenomenon was perfectly controlled, which suggested that it was imposed on the lugs from outside.

She fell silent and let the implications of that sink in. And then the recorder shifted to al-Qatan, who made a final summing up, stating conclusions that were little more than questions, conclusions that in the end came to a simple confession of ignorance.

Yet, he said, we know it could be done: We have seen it. Sooner or later we'll discover the secret.

End of presentation. I told the windows to shift polarization and admit the sun.

The faces of the deputation seemed bleached in the sudden hard light; there were no shadows, no reliefs, only pale blobs with eyes. The eyes were turned toward me.

"I'm with the Father," I said. "Let's call it a miracle and say the hell with it."

No one laughed. I rose from my chair and thanked them. "I have luncheon ready for you in the dining room, and I've had some good wine brought up from the cellar. I won't be able to join you, unfortunately; I have an appointment to speak with Mr. Odje, and I don't want to offend him."

They rose and thanked me for watching their presentation, their voices sounding hollow, insincere. They had come all this way, given up all these years, and for this?

I showed them to the dining room and bade them eat. I had a human cook, Eirene, who despaired of my small appetite. This was a chance for her to show off her talents. I walked to my study and saw my own midday meal sitting on a leaf of my desk: bell pepper, tomato, olives, cheese, a little oil, a small carafe of wine. A message light was blinking. I looked at my watch. It was too early for Odje.

"Mr. McGivern wishes to speak with you," the house said.

"Very well. I'll accept video."

When the picture came, it showed the old mosaics that had been lovingly transplanted to my bathroom. McGivern had gone there to wash his hands and place the call, presumably so the others wouldn't see.

"Doran," he said, "I'd like to talk to you. It won't take long."

"Is later this afternoon okay?" I asked. "I really do have a call placed to Odje."

He nodded. "After lunch then," I said and broke the connection. I had finished half my salad when the call to Odje came through.

The president of the United Communities of Earth was in New York, and the muted light of dawn shone through the clear window behind him. Like me, he was an early riser. He was a dignified man of middle years, his skin ebony, his dress somber. A Diehard of a faction that considered me Lucifer incarnate, he nevertheless handled our inevitable meetings with grace and aplomb. He bore, like most of the Diehards I'd dealt with, an old-fashioned personal integrity that made me warm to him instantly. I think, religion aside, we liked each other.

The business concerned the Red Sea underwater leases. A dozen or so families had built homes beneath the surface there, where from their windows they could look out onto the living beauty of the coral reef and all its creatures. I was trying to acquire titles to their places, offering to swap them for improved homes in the Pacific. The government possessed certain rights in the Red Sea, and I was trying to buy those too, as part of the package, in exchange for liberalization of other treaties elsewhere. It would clearly be to Odje's advantage to accept, and with our robots in attendance, we worked out the details easily.

"It's curious," he said afterward, making a tent of his fingers and looking at me with narrow, measuring eyes. "There's a pattern to your purchases in the area. It's as though you intended to depopulate all Egypt and Sinai. What are you planning to do with the place once you have it? Rebuild the pagan temples, as you've done in Greece?"

I grinned. "Perhaps. Would that offend you?"

He shook his head. "No," he replied. "You attract no worshipers to your shrines, if that was ever your intention. You rebuilt only dead monuments to ancient vanity, and magnificent as they are, they are nothing compared to the cathedral God has made of his earth."

"That is true, Mr. President," I said. "Though I remember that God needed a little help in cleaning up his cathedral a while ago and it was I who had to pick up the litter."

A sylphlike smile crossed Odje's face. "Even the devils do God's will in the end, though they know it not," he said. "Have a good day, Mr. Falkner."

"Mr. President."

His image vanished. I frowned and drank a sip of wine. How much of my plan could be deduced by the patterns of my purchases, those I'd made in Mesopotamia, Africa, China, and now Egypt? It could be argued, I suppose, that all I was doing was enlarging my holdings, holdings that already encompassed most of the surface of the planet; but how much could be discovered by my choices in acquiring the bits that were still in other hands? Perhaps as a blind I'd have to arrange some purchases I hadn't planned on.

I finished my lunch, ordered coffee and told the house to tell McGivern I'd see him when it was convenient. During the interim I called up my purchasing comp, reviewed my plans for the next few years, and asked my world modeling comp to tell me if the purchasing comp's overall pattern was discernible. WORKING, it told me. Then McGivern was knocking at my door; I told the comp display to vanish and the door to let McGivern in. He smelled strongly of his after-luncheon cigar.

"Come in, Brian. Have a seat. Would you like a brandy?"

"Thank you, no." Sitting down, he tented his fingertips and frowned slightly, looking at me with wary intelligence. His expression was so like Odje's that I found myself grinning.

"What's bothering you, Brian?' I asked.

He spoke carefully, each word considered. "You know what it would mean to us— us being the human race— if we had some form of teleportation. If we were no longer bounded by the speed of light."

"It would be a revolution."

"A revolution as all-encompassing, Doran, as your own."

I bowed, conceding the compliment. If compliment it were.

"The worlds are too far apart," McGivern said. I sipped my coffee. "Human space is huge, a hundred light-years across. Getting bigger. It's diverse, but it's also provincial. Each planetary system has a homogeneous culture, but they're isolated from one another, getting set in their ways. Even the spacers who live between planets exist in their own zero-g environment and have no real interaction with the natives of the planets they visit. There's not enough communication between systems to create any kind of dynamic between them, any contrast that can lead to analysis and growth. Your revolution went far, Doran, but it's dying."

It was true, I knew. The information that came in from human space indicated, after the centuries of expansion, an end to growth, a cultural stasis of the planets based on the stability provided by the energies of the Falkner Power Systems, the comforts of cybernetics and the isolation of one star from another. The birth rate was down considerably, and with it the percentage of young people, with their more flexible and adaptable minds. Suicide, voluntary or the more subtle sort, was way up. The Diehards were too few and too short-lived to make a difference anywhere but on Earth. Any science being done was clarification of what had gone before; most literature and drama were merely sophisticated refinements of earlier forms.

An elderly twilight, I thought. The senility of mankind, where the only pornography is death. What happens to such a system when a being can move in an eyeblink from one world to the next? Where all isolation is ended, where all provincial boundaries are down?

A revolution, as McGivern had said— as encompassing a revolution as the last couple I'd made. The unleashing of a social force so enormous that it would be impossible to foresee, or attempt to control, its effects.

"You have yet to explain," I said, "why I have to lead this new revolution. Al-Qatan said it best: Now that we know it can be done, sooner or later we'll do it. It might be done already, back on Kemp's."

"On Kemp's they weren't anywhere near it," he said. "It'll take years, Doran, and effort. And brilliance. And a certain amount of prestige to back the project. So far as I can tell, you have them all to spare." He leaned forward in his chair, his eyes intent. "You were the last and greatest pair of revolutions, Doran," he said. "Humankind was set in a pattern that would have led to its extinction, and you took the bits of the pattern and tore them apart and put them together in your own image. You made something new from a ruin, and from where I sat, you seemed to be enjoying yourself. Two revolutions, Doran. Wouldn't you like to make it three?"

And shake up this complacent humanity I had so unwittingly created? I propped my sandals on my desk and took a sip of wine. "I must admit the idea has a certain piquant attraction," I said. "But I'm hoping to build the next revolution from here."

He gave a brief nod, as though confirming something to himself. "Your centaurs," he said.

"My centaurs."

"Another intelligent race to contrast with our own and provide a dynamic interaction." He tugged at an ear. "It will take centuries."

"I've got them."

He tapped his fingers on the arm of his chair as he thought; then he looked up at me. "But they don't need you," he said. "They'll do it on their own, sooner or later."

"So will al-Qatan and the others."

McGivern sighed and rose. "So: an impasse," he said. "You'll do what you want, I know. I'd just hoped you'd be more... flexible."

I pulled in my legs and stood. "I promised you I'd see your people, Brian," I said. "That's all."

"Yes. They've come light-years for this morning. I suppose they shouldn't be disappointed."

I finished my coffee. "I'll join them at the table now if you think it'll make them feel better. But I didn't ask them to make the trip."

"No," he said dryly, "I did." He reached into his pocket and took out a message block. As though reluctant, he held it out to me. "Mary asked me to give you this privately. I don't know what it says. I should have given it to you last night but it didn't seem like the right time."

I took it, feeling it warm on my palm. "Thank you," I said. How well, I wondered for the first time, did Brian McGivern know Mary Liddell? I put the cube on the desk. "I'll join your people shortly for brandy."

"They'll be pleased to see you again," he said formally. There was suddenly a strange awkwardness in the air, as though we'd just met one another for the first time and didn't quite know what to say. There was a funny ache in my throat, and I suspected in his. I wondered what the hell was going on. I opened the door.

"I'll see you in a few minutes."

He bobbed his head and began to make his way out.

"Brian," I said, and he stopped in the doorway, looking at me questioningly. "If I do this thing, it might not be possible right away," I said. "There are some good-byes I'd have to say."

"I understand.' He gave a faint smile. "I'd like to see the centaurs again myself. I hope I'll have the chance."

"I'll see what I can do," I said and let him out.

He'd thought I'd meant the centaurs; a natural mistake for him to make.

There were worse things at large in the world— and to one of them I owed a great debt.

With what emotion does one regard a love thirty years dead? It is not, assuredly not, to hear the sounds of seraphs strumming the old, old songs in one's ears, to recall days of frolic on grassy hillsides and to find passion blazing anew in one's breast, hopeless and redeeming. I had spent twenty intervening years married to someone else; I'd fathered and helped raise two children; there had been other lovers, other desires.

Yet there was something unsettling about seeing her, the knowledge of a ghost not properly laid to rest. Symbolized in this transcript by that distant, sterile and very English use of the word "one," keeping one's distance from one's feelings, old man, trampling out the vintage where one's grapes of candor lay. Why couldn't I have used a more intimate adjective? Me, my, mine. My ears, my breast, my former lover. So.

I will not take your gift, she had said.

I will not watch you die, said I.

And thus it had ended. After her emigration we had exchanged letters, proper letters written on paper. No video. There had only been long reams of epistolary prose, but those had necessarily proved fairly pointless. The knowledge that one will have to wait twenty years for a reply to a letter can squash the life out of correspondence before it begins. So had it been with Mary and myself, as it had been before with my former wives, with many of my children, with friends and lovers and enemies whom I had sent, willing or unwilling, to the stars. Once, indeed, I had received a ponderous, official condolence on the suicide of one of my sons, and I had to frown for a moment and think who it was: Ah, yes, Julie's boy. I hadn't heard from him myself in scores of years. I hoped his bitter last thoughts had not been of me.

In another case I had found myself involved, unknowingly, in a wholesome carnal tangle with my great-granddaughter, the offspring of a child who had long ago emigrated. The girl had known but hadn't found the fact worth mentioning.

Nor, after contemplation, had I.

Sad facts all, I'm sure; saddest of all the fact that not one of them is out of the ordinary. Enough to make a person hope that something may come from this teleportation business.

Mary's image was frighteningly close in this small study, her head and shoulders larger than her image in the other recording, larger than life even, creating a forced intimacy I did not desire. The lines in her face were clear, and I could see gray in her silver hair. I pressed back in my seat against its reality. Her message was simple, sensible. Admirable. True.

I may, she said, not be justified in the assumptions— fears really, not assumptions— that lie behind this communication. I apologize if I'm wrong. But I won't feel comfortable with myself unless I tell you this.

You owe me nothing, she went on. Do not come on this journey because of anything I said or did not say. I am happy with myself; I am happy with my decision; I will not change. I am going to have myself frozen until the team leaves; that decision is not based on any regrets but on a wish to see this project through.

She raised her hands, one clasped over another, and touched her thumbs to her chin. I felt a flash of recognition at the gesture, for the way her cool, dark eyes looked steadily at mine; and I felt as well a surge of horror at the aged, veined, still-graceful hands.

You are free, she said. Free of anything I do or say, and of any consequence. You may rest assured that all hurts are forgiven, all loveliness remembered, and treasured. I am busy and content and loved. I hope you are the same. Bless you.

The image faded and I was suddenly aware of my heart beating fast in terror. I took a breath and looked with surprise at the sweat on my palms. I wiped my hands on the hem of my chiton. I was trembling for a drink. I wondered if this is how senility strikes.

I felt surprise at the horror I was feeling. Mary was in what was once called the prime of life, physical and emotional maturity, the age of greatest social accomplishment. I had once been as physically old as she, and I hadn't experienced it as a difficult time.

But now the sight of her was terrifying. And not simply because she was a Diehard— hadn't I just taken a call from Odje, who was older than Mary, without this kind of reaction? No, somehow it frightened me because it was Mary.

She was living an obscenity. But I, at least, was absolved from any complicity. I thanked her for that.

With what emotion does one regard a love thirty years dead? In this case, my case, with fear.

I went to join my guests and I ordered up the good brandy. "Absent friends," I said as I lifted my glass, and saw Brian McGivern's somber, searching eyes looking at me as he drank.

I spent the afternoon with them, chatting about Delphi as it was and had been, about Greece and the monuments they had seen ruined or being rebuilt. As I escorted them back to Ismenos's little hovercraft, I gave them a brief tour as we wound down the Sacred Way; I told McGivern I'd be in touch with him; and then I stood and made my way back up the hill.

KNOW THYSELF, the graven letters read, the words of the Seven Wise Sages.

Nice try, fellas, I thought. But you've missed my point. I'm over eight hundred years old, and it's been ages since I've managed to surprise myself at all.

Until this afternoon. Until I met an image with fear.

I went up the hill to my dinner, and with it a bottle of wine. I played the blues late and finished the bottle.