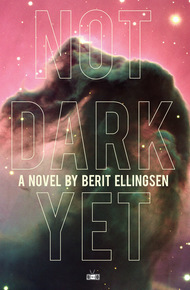

Berit Ellingsen is the author of the novels Not Dark Yet andUne Ville Vide (PublieMonde), and the short story collection Beneath the Liquid Skin (firthFORTH Books). Her work has appeared in W.W. Norton's Flash Fiction International, SmokeLong Quarterly, Unstuck, Litro, and other places, and been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and the British Science Fiction Award. Berit divides her time between Norway and Svalbard in the Arctic.

Brandon leaves his boyfriend in the city for a quiet life in the mountains after an affair with a professor ends with Brandon being forced to kill a research animal. It is a violent, unfortunate episode that conjures memories from his military background.

In the mountains, his new neighbors are using the increased temperatures to stage an ambitious agricultural project in an effort to combat globally heightened food prices and shortages. Brandon gets swept along with their optimism, while simultaneously applying to a new astronaut training program. However, he learns that these changes—internal, external—are irreversible.

A sublime love story coupled with the universal struggle for personal understanding, Not Dark Yet is an informed novel of consequences with an ever-tightening emotional grip on the reader.

I have been a fan of Berit's ever since I read her short story collection, Beneath the Liquid Skin. She had a unique voice and I definitely wanted to read more. My dreams have come true with this new novel, just out from Two Dollar Radio. It has already received a starred review in Publishers Weekly, and was listed as Buzzfeed's Top 5 books to read in November. I have a feeling this is just the beginning of many more accolades to come, especially given the novel's beautiful writing, relevance to our modern life, and wonderfully surreal aspects. Be the first on your block to read it now. – Ann VanderMeer

"Fascinating, surreal, gorgeously written, and like nothing you've ever read before, Not Dark Yet is the book we all need to read right now. It is art about science, climate change, and activism, and it vitally explores how we as people deal with a world that is transforming in terrifying ways."

– BuzzFeed"Suspenseful and haunting...Ellingsen projects a feeling of encroaching darkness on every page, and this tension guides the narrative like a purposeful current. Expansive and unsettling descriptions make it easy to fall under the story's spell. This is a remarkable novel from a very talented author."

– Publishers Weekly (starred)"Berit Ellingsen's new novel is a surreal, unpredictable work bringing together environmental devastation, a nuanced portrayal of a relationship, and questions of space exploration. Does it get under your skin? Oh yes."

– Vol. 1 BrooklynSOMETIMES, IN BRANDON MINAMOTO'S DREAMS, he found a globe or a map of the world with a continent he hadn't seen before. When that happened, a flash of excitement ran through him and he hurried on to explore the new place. Now he had the same feeling of sudden, unexpected discovery, and started running down the fir-shaded hill, stubbed one boot against a stone, stumbled in the soft, rain-sodden ground, nearly fell, and slid the remaining distance to where the grass-covered slope ended in a short overhang of roots and straw. In the pebble-strewn stream that ran beneath the beard of vegetation, he nearly twisted his ankle, making his ninety-liter backpack wobble and the steel canteen bang against his hip, nearly toppling him. But finally, he stood before the blue door on the wooden terrace, his boots caked with mud, his heart beating hard, and the air fragrant with the scent of pine sap and heather and earth. While he caught his breath, he took in the red walls, the unpainted deck, and the gabled roof where the dark eyes of solar cell panels gleamed even in the overcast day.

He felt weightless, only the pressure against the soles of his feet signaled the substance of the rest of his body. The cabin, the heath, the world shone inside him, in an intimate, shared existence. He closed his eyes and there was no body, and no world either, only the simple, singular nothingness he recognized as himself.

When his breath was less ragged and he could focus on something else other than gaining air, he took out his wallet and unzipped the pocket in the back where a small key bulged the brown leather. He pushed the key into the rust-spattered lock and turned it once. It didn't shift. He tried one more time, putting more weight on the key. The door held an antique ebony handle and had been painted a clear, deep hue without having been sanded down first, leaving craters and fault lines from multiple layers of pigment visible in the surface. A diamond-shaped pane of unevenly sealed glass sat high in the wood, but the window was dark and revealed nothing of the inside. He closed one hand around the handle and rattled the door while using the key with his other hand. The lock didn't turn this time either, but the door snapped back into its unpainted frame. He gave the door a good push and tried the key again, and this time the lock gave way. He shook his hand from its tight grip on the narrow metal and returned the key to his wallet. Then he pushed with both hands on the handle. The wood creaked open and swung wider to invite him in.

He stooped to avoid the frame and closed the door. Further inside the ceiling grew higher and more accommodating, with more than enough room for him to stand at his full height.

The interior of the cabin was a single space, about five meters in the short dimension and eight on the long. The floor was covered with wide hardwood planks the color of dried blood, edged with fake black nails painted at the ends. He almost laughed when he saw it. The maritime-style ship-deck floors had been popular some years ago, in executive offices, high-end stores, and newly built apartments, but then fallen harshly out of fashion. It had been a long time since he had encountered one. The former owners must have bought the flooring on sale or acquired it from another building, and transported it all the way up to the heath, far away from the ocean and the maritime look alluded to.

All four walls lacked baseboards and the northwest corner missed covering, but a few planks had been left on the floor. If there were tools in the cabin's lean-to shed the corner would be easy to fix. Otherwise, he'd buy a hammer, saw, and nails the next time he hiked through the heather to the nearest town. The cabin smelled of dust with an undertone of mold. He inspected the walls and ceiling, but found no stains of moisture or blotches of fungi.

The long wall to the east was occupied by the kitchen and consisted of a few cupboards in a delicate eggshell blue, a laundry sink in steel of a type he recognized from his grandparents' old house on the eastern continent, a small refrigerator at the end of the worktop, and a gas stove with a fat canister of propane gas beneath it. The kitchen was illumined by a rectangular window above the sink, the dim afternoon light bounded by once-white frilly curtains. On the floor was a rug made from rags in primary colors, the old fabric now tangled with dust. The stove was a large four-ring camping cooker mounted on a wooden frame. He hunched by the canister and sniffed. He detected no leakage, but he'd have to check the gauge and tubing in full daylight. The fridge was empty, but clean, a power cord curling to the socket in the wall behind. The cupboards held stacks of plain white plates in two sizes, large and small, and cups and saucers in the same non-patterned design. Some of the glassware was cracked and chipped at the edges. The drawers by the sink contained a red mesh tray of stained cutlery and some dented pots and pans, all gray with dust and the sticky remnants of spider webs. The kitchen ended at the blue-painted door that led to the deck outside.

A tripartite panorama window took up almost the entire west wall, looking out on the moor and the mountain range that constrained it. Dusk had almost swallowed the sky, and dark clouds rushed toward the distant peaks. The draft from the three large windows was palpable, even in the middle of the room. The white frame was gray with dust and the sill beneath it littered with curled-up spider husks and desiccated flies. There were some mouse feces as well, and lumps of brown fur, but he neither saw nor heard any other signs of rodents.

By the north wall stood a sagging three-seat sofa with printed purple poppies the size of human heads, and a long, frilly skirt. Leaning against the south wall was an old lime-green spring mattress. When he touched its surface dust whirled up, yet the smooth fabric seemed dry and free of mildew. He went over to the door, opened it to the dimming evening, and carried the mattress to the deck. There he hit the fabric repeatedly to get the worst of the dust off, then stood the mattress on end and bounced it a few times. More particles left to spread on the evening breeze. He sneezed, slapped the mattress some more, then carried it back inside and shut the door against the coming night.