Melissa Scott is from Little Rock, Arkansas, and studied history at Harvard College and Brandeis University, where she earned her PhD in the Comparative History program. She is the author of more than thirty original science fiction and fantasy novels, most with queer themes and characters, as well as authorized tie-ins for Star Trek: DS9, Star Trek: Voyager, Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis, and Star Wars Rebels. She won Lambda Literary Awards for Trouble and Her Friends, Shadow Man, Point of Dreams (written with her late partner, Lisa A. Barnett), and Death by Silver, written with Amy Griswold. She also won Spectrum Awards for Shadow Man, Fairs' Point, Death By Silver, and for the short story "The Rocky Side of the Sky" (Periphery, Lethe Press) as well as the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. She was also shortlisted for the Otherwise (Tiptree) Award and the Midwest Book Awards. Her latest short story, "Sirens," appeared in the collection Retellings of the Inland Seas, and her text-based game for Choice of Games, A Player's Heart, came out in 2020. Her solo novels, The Master of Samar (2023) and Fallen (2023) are both available from Candlemark & Gleam.

They traveled the starlanes together, bound by their desire for freedom and by the call of destiny.

Imagine a future in which alchemy, the carefully manipulated power of the elemental harmonies, has made interstellar flight a reality . . . human civilization thrives — with variations — on numerous far—flung worlds . . . and Earth is little more than a haunting memory — a legendary planet lost during the Millennial Wars.

Silence Leigh is luckier than most of the women in this future. Trained as a pilot —a rare privilege for a mere female — and more than happy to spend her life steering her grandfather's ship, The Black Dolphin, between stars, she had managed to avoid most of the restrictions governing women on the worlds of the Asterion Hegemony. Until her grandfather died.

With no legal status, Silence needed a male guardian in order to inherit the Dolphin. But her greedy Uncle Otto was so unconcerned about his niece's welfare that he neglected to show up in court. And she refused to become the ward of a powerful, opportunistic local merchant whose interest in her was only slightly less than his interest in her ship.

Frustrated by her helplessness, infuriated by the knowledge that she would be cheated out of her inheritance anyway, Silence was just about convinced that her career as a pilot had come to a bitter end — when Captain Denis Balthasar stepped in.

Baithasar needed a pilot for his ship, Sun—Treader—a woman pilot, he said, which was suspicious in itself. But Silence's fears about the enigmatic stranger were soon replaced by astonishment. For the Captain had an odd but honest proposal to make. Literally. He wanted her to join him and his engineer, Julian Chase Mago, in a three—way marriage–a marriage of convenience that would legally extend Balthasar's own, highly desirable Delian citizenship to his partners.

It was an offer Silence could not refuse: freedom for all of them — the kind of freedom only a star-traveler could know. And hope for the future — a future that would take them to a pirates' stronghold in space, where they would be given a chance to strike back at the Hegemony; a future in which they would confront the awesome power of the magi, whose alchemy controlled the universe; a future that would set them on a dangerous path starfarers had been seeking for centuries: the road to Earth.

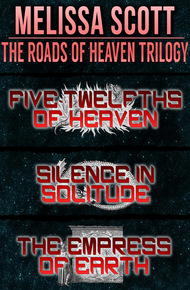

Includes Five-Twelfths of Heaven, Silence in Solitude and The Empress of Earth.

Space Opera at its best. Silence Leigh is defrauded from her inheritance and dragged into a deadly political struggle against the dread and the glory of Magi's power. – Steven Savile

"Scott had me hooked from the first "The" to the final "victory"."

– James Nicholl Reviews"…the world is so startlingly original and so impressively well-designed and thoroughly expressed (and so smoothly, with a beautifully slow reveal to the reader) that it defies comparison to any other starfaring adventure SF I've read. I fell in love with Scott's world within the first fifty pages…after one taste, I think most people will want more. Highly recommended."

– Eyrie.org"Space opera for grown-ups — that's my idea of heaven."

– SF ReviewsThe court complex was crowded as it always was, jammed with contentious Secasian natives babbling away in the local variant of the Hegemony's official coine. Silence Leigh edged her way through the crowd toward the entrance of the Probate Court hall, trying not to draw too much attention to herself. For all that she was decorously veiled, the stark mourning cloth drawn so tight across her face that she could barely stand to breathe the stifling air of the corridors, she had neither man nor homunculus to escort her, and an unaccompanied woman was fair game at any time. Almost as if conjured by the thought, a bearded man jostled against her, trying to see her face beneath the veil. Silence turned slightly, so they met shoulder to shoulder, refusing to let herself be pushed aside. The man grinned down at her, then was lost in the crowd. Silence felt a surge of pure, screaming fury. In the three weeks since her grandfather had died, stranding her on Secasia until his affairs could be settled, she had had to put up with that sort of harassment almost daily.

Then her anger was drowned by the numb misery that seemed to follow any thought of her grandfather's death. It had been so unexpected, had given her no time to spot the warnings of ill health or sheer old age, no time to prepare herself for the unthinkable. There had been only the call from the planetary police, then the chill, sterile hall where she had identified the body, and finally the search for her uncle, the third member of the crew, whose signature was required before the police could release the body. She still could not fully understand what had happened. Bodua Leigh had been an old man, true enough, but not that old. Certainly he himself had felt no warnings of impending doom: he had left his business in its usual state of inspired confusion. Silence shook her head. Her grandfather had been a brilliant businessman in his way—it had been his talent for profitable improvisation that had made him the chief man of business for the richest oligarch on Cap Bel. But that had been ten years before, before the Hegemony had conquered the Rusadir worlds, and in passing ruined the oligarchs of Cap Bel. Bodua Leigh's methods were less suited for managing the affairs of a single starship, trading along the fringes of the Hegemony. But he had refused to change, and now she was paying the price of his stubbornness.

Two men were waiting at the door of the Probate Court, both in the dark red livery of the court's staff. The older of the two held out a hand to bar her from entering.

"This is the Probate Court, miss. Women's Court is two floors down."

"Yes, I know," Silence answered.

"You're a litigant, then?" The guard's expression made it quite clear that he found that hard to believe but, given the Hegemony's laws, there was no other plausible explanation.

"Yes, I am."

This time, the off-world cadence of her speech betrayed her, and the two guards exchanged glances. The older said, "This way, miss. You're familiar with Hegemonic law? You know you need a guardian—a male guardian—to speak for you in court."

"Yes," Silence said, and was unable to keep the bitterness out of her voice. "I'm meeting him here."

"I see, miss." The guard's expression showed only too clearly what he thought of a guardian who would allow a woman to travel alone to the court complex, but he said nothing. He escorted her to the benches reserved for the litigants, handed her to a seat, and then returned to his post. Silence loosened her veil slightly, letting in some of the cooler air of the courtroom, then glanced nervously around the long hall. The Probate Court was even more crowded than the corridors, the benches on the floor of the hall filled to capacity with both local notables and off-worlders who thought they might have an interest in one of the many wills to be proved today. The gallery was equally crowded, filled with idlers from the port come to see the show. They were in a holiday mood, she thought sourly, and why not? There was a special attraction today: It was not often that an off-worlder died so magnificently intestate, or with a woman as his sole heir. She scanned the hall again, looking for the pudgy figure of her maternal uncle. There was no sign of him in the sea of unfamiliar faces. Where are you, Uncle Otto? she thought desperately. I can't do anything without you to sanction it.

Then her lips thinned slightly. She could guess where her uncle had gone. There were only two choices. Either he was drugged in one of the many smokehouses around the port, or he was being swindled by a dealer in curiosities, feeding his obsession with lost Earth. No, she corrected herself, it hardly qualified as an obsession. The explorers and magi who sought Earth simply because the true roads had been lost during the Millennial Wars, or for the lost knowledge, or because Earth was mankind's proper home were obsessed. Otto Razil was interested only in the profits involved. The last time he had tried to persuade her grandfather to make a search, Razil had quoted a possible profit of over five million Delian pounds. The old man had laughed at him, and Razil had stalked out, muttering something about going where he would be appreciated. Silence's eyes filled with tears she could not afford.

The group talking softly in front of the judge's high bench broke apart, and the clerk-of-court consulted his sheaf of printouts.

"The case of Bodua Kesar Leigh," he announced, his voice carried to the corridors and waiting rooms by the microphones embedded in the heavy torque of his office. "Will the interested parties come before the face of justice?"

Silence hesitated, hoping against hope to see her uncle's stocky figure appear at one of the doors. There was movement at the farthest door, someone shoving his way into the hall, and she sighed her relief. Then the figure came clear, and a merchant in long robes shifted sideways along a rear bench to make room for his colleague. Silence whispered a curse.

"The case of Bodua Kesar Leigh," the clerk announced again, and Silence shook herself. She gathered her full, ankle-length coat around her, and edged her way out into the open space before the judge's bench. The old man peered down at her, his wrinkled brown face not unfriendly.

"Is there no one else?" he asked the clerk, who shrugged. "Call again."

The clerk repeated his call, but there was no response except for an appreciative chuckling from the gallery.

"No one at all?" the judge repeated, frowning. "Young woman, come here."

Silence did as she was told, staring up through the narrow slit in her veil.

"Now, what's this all about, girl?" the judge asked. "Surely you know the Hegemony's laws."

"Yes, your Honor," Silence said carefully. "I've been told that I cannot speak for myself, but must be represented by a male guardian, and I had made arrangements for my uncle to be here. But he isn't, and I'm from Cap Bel, in the Rusadir. I don't know anyone else who'd be able to speak for me."

"Your uncle's name?" the judge asked.

"Otto Razil."

The judge gestured to the clerk. "Call Otto Razil."

The clerk nodded, and adjusted his transmitters to reach every area of the court complex. "Otto Razil! On pain of fine and forfeit, answer to the Court of Probate. Otto Razil!"

Silence held her breath, but refused to look at the open doors of the hall. Razil wasn't coming, that much seemed clear; he was as useless as he'd always been, and she was stuck with the consequences yet again….

The judge cleared his throat and leaned forward. "We can't wait all day, girl. You can either hire an advocate—" One withered hand swept out, indicating a bench of shaven-headed lawyers toward the front of the hall. "—or the court will appoint a guardian for you. Which will it be?"

"My money is tied up in my grandfather's estate," Silence said, forcing herself to think constructively. "Unless I can draw on that, the court will have to appoint a guardian."

"Since it is the court's responsibility to decide the rightful owner of the estate," the judge said dryly, "you could hardly be permitted access. The court will appoint a guardian. Your name?"

"Silence Leigh."

The judge raised an eyebrow at the old-fashioned name. "And your relation to—" he glanced at his printout "—Bodua Kesar Leigh?"

"My grandfather," Silence answered, then corrected herself, remembering the Hegemony's laws. "My father's father."

The judge nodded. "The uncle you mentioned, he's not of agnate kindred?"

Silence hesitated. "He's my mother's brother."

"Not the agnate line," the judge murmured, noting that on his printout, then signaled to the clerk. "There's quite a bit of property involved, young lady."

The clerk rose to his feet. "Is there any free man, citizen of Secasia or other world of the Asterion Hegemony, who will, under the provisions of the Tabiran Laws and the decree of the Hegemon, act as guardian for this woman, Silence Leigh, granddaughter and heir of Bodua Kesar Leigh, provided thereby that guardianship is not taken away from any legal guardian? A fee of three solas is offered for the service."

There was an excited stirring in the gallery—three solas was a day's wage on Secasia—and some quick exchanges among the merchants on the floor of the hall, the latter prompted by the preliminary assessment of Bodua Leigh's estate, now displayed on the viewscreens that ringed the hall. The sound died away in a disappointed mumble as a man rose to his feet in the front row, lifting his hand to attract the judge's attention.

"May it please the court, I'm willing to act as Miss Leigh's guardian."

The judge nodded gravely. "Come forward, and give your name."

The man stepped out from the row of merchants, his hands folded politely in the sleeves of his crimson coat. Prominent on one sleeve was the mark of Secasia's largest trading house. "My name is Tohon Champuy, merchant-master and freeholder of this world. I have often had dealings with the young lady's grandfather, and know something of his business."

"No!" Silence bit back the rest of her startled exclamation. Champuy knew her grandfather's business, all right, but only because he'd been trying to cheat the old man for the past five years. "Sir, your Honor, rather, can I refuse?"

The judge frowned. "On what grounds?"

"Merchant Champuy's been trying for five years to buy Black Dolphin, or to get Grandfather under contract," Silence said. "And at scrap prices, too, for a starship with a new keel and engines—" She broke off, realizing that she was babbling, and Champuy spoke quickly into the silence.

"I don't like to contradict a lady, your Honor, but the Black Dolphin isn't worth much more than the scrap price. In fact, that was one of the reasons I offered Bodua Leigh a contract, in hopes that he'd be able to repair the ship properly. I'm sure the strain of handling so battered a ship hastened his death."

"That's not true," Silence said.

The judge glanced dubiously at her, then touched buttons on the control pad embedded in the surface of the bench. Screens slid across the upper windows of the hall, dimming the light considerably. A display globe descended slowly from the ceiling, a scale replica of Black Dolphin coalescing in its center. Silence's eyes filled with tears at the sight, and she shook them away angrily. There was no time for that now, she told herself. If she wanted to keep the ship that was rightfully hers, she would have to fight for it, and she could not afford emotion.

"What was your position aboard the Black Dolphin, young lady?" the judge asked.

"I am the pilot, your Honor."

"The pilot?" the judge repeated incredulously, and a murmur of surprise rippled through the hall.

Silence ignored it, used to being an oddity. "Yes, your Honor."

"A pilot has very little to do with the maintenance of the ship," Champuy said quickly. "I am certain that Bodua would not have burdened a woman—"

"Wait, please." Silence clasped her hands in supplication, playing for time. She had been thinking like a man, in terms of ships and cargos, the economics of a star-traveller's life, but that wouldn't help her in the Hegemony. Only the Hegemony's peculiar customs could rescue her—if she could make them work for her. "Sir, I don't want him as my guardian because—there's another reason he wanted the ship, battered as it may be. He wanted not only the ship, but her pilot—myself." She bowed her head as if in shame, scanning the surrounding faces from under the protection of her veil. "My grandfather, all honor to his name, wouldn't sell."

For a moment, she thought she had overdone it, that the judge and the staring spectators would catch her lie, but then there was a swelling mutter of voices from hall and gallery, angry and indignant. The judge glared at Champuy, who spread his hands wide.

"Your Honor, the young lady is distraught. I assure you, my offer was genuine, and my concern for her merely fatherly, prompted by my long association with her grandfather. I will state, in open court and under binding oath, the terms I offer. I will purchase Black Dolphin from her—at the assessors' price, even though I believe it to be an inflated figure—and I will keep Miss Leigh on as pilot, if she should choose to stay." He turned and spoke directly to the pilot. "You will not find a better offer, young lady."

I know a threat when I hear one, Silence thought. To the judge, she said, "Your Honor, I do not want him for my guardian."

The judge glanced from her to the merchant and shrugged irritably. "Very well. Merchant Champuy, the young woman has declined your services as guardian, and I will uphold her refusal. Please stand aside."

Champuy bowed, expressionless. "As your Honor pleases."

The judge nodded to his clerk, who rose to his feet. "Is there any free man, citizen of Secasia or other world of the Asterion Hegemony, who will, under the provisions of the Tabiran Laws and the decree of the Hegemon, act as guardian for this woman, Silence Leigh, granddaughter and heir to Bodua Kesar Leigh, provided thereby that guardianship is not taken away from any legal guardian? A fee of three solas is offered for the service. This is the second time of asking."

There were a few stirrings among the lesser merchants toward the back of the hall—after all, there were potential profits to be made from the guardianship of a woman who was heir to a starship—but Champuy turned to look blandly at them and the noises subsided. Silence winced. Champuy was one of the most powerful merchants on Secasia by virtue of his combine directorship—certainly he was the most powerful in the hall. If he had some scheme, none of the others would risk interfering in it.

The judge leaned forward, scowling first at the more solvent audience on the floor of the hall, then up at the galleries. "This is absurd," he exclaimed. "Is no one willing to fulfill his obligations—even for three solas?"

There was a burst of conversation in the gallery then, as the unemployed men seated there realized that they were being given the chance to earn a day's pay, and to have some fun in the process. She had outsmarted herself, Silence realized, and her stomach twisted. She had avoided the Champuy's direct guardianship, but a guardian chosen from the gallery would have no reason to try to protect her interests, as one of Champuy's rivals might. In fact, to avoid offending Champuy, and to buy favor and perhaps a job, anyone from the gallery would cheerfully sell Black Dolphin, regardless of her wishes. Under the Hegemony's laws, there was nothing she could do to stop it. If only the Rusadir hadn't resisted its absorption by the Hegemony ten years ago, she thought greyly. The Hegemon might have let us keep a few of our old rights…. But there was no use wishing. She was going to lose the Dolphin, and with it her only chance to lead a star-traveller's life. Oh, she would get enough money for ship and cargo to take her back to Cap Bel in style, to let her live without a husband, or provide her with a highly respectable dowry, as she chose. But without a ship, she would have no way of proving herself as a pilot. It had been hard enough to get her license for the Rusadir, and to have it extended to cover the Hegemony, when she was twenty and her family had influence with the Commercial Boards. Now, with the Hegemony in complete control of the Rusadir, and threatening to expand into the Fringe, there wasn't a captain alive who would make trouble for himself by hiring a woman pilot. Silence closed her eyes, momentarily grateful for the veil that hid her despair.

"Excuse me, most honorable. May I speak?"

The call came not from the gallery but from the back of the hall. Silence looked up quickly, but could see only an arm, encased in star-traveller's leather rather than Secasian rosilk, waving above the heads of the men standing behind the last row of benches. Then the arm's owner worked himself free of the crush, stumbling over someone's leg as he stepped out into the aisle.

"I beg your pardon, sir, but I believe I can help."

The speaker was not a particularly impressive man, of average height, hawk-faced and greying, but he was a star-traveller—a captain, from the medallion slung around his neck. Silence held her breath as the judge glanced from her to Champuy, who was frowning openly. The latter seemed to decide the judge.

"Come forward, Captain."

"Thank you, sir." At the head of the aisle, the star-traveller bowed twice, first to Silence and then to the judge. "If the court allows it, I'm willing to act as the lady's guardian—given her consent, of course."

"Your name and status?" the clerk asked.

"Denis Balthasar, owner-captain of the Delian ship Sun-Treader." He held up a hand to forestall Champuy's immediate protest. "I am a citizen of Delos, but I have commercial rights—citizen status in the courts—as granted under the Johannine Law to persons doing a significant amount of business in the Hegemony." He reached into a pocket of his jacket and produced a thin metal disk slightly smaller than his palm. The clerk took it and fed it into one of his machines.

"Your identification disk?"

Balthasar slipped his medallion from around his neck and handed it over. The clerk consulted his machines again, then returned both disks. "Your status is confirmed."

"One moment," Champuy exclaimed. "Your Honor, you cannot uphold the right of a mere Delian, even one with commercial rights, and give him precedence over Secasians born and bred."

The judge looked at him with undisguised distaste. "Merchant-master Champuy, the majority of Secasians present today show no desire to do their civic duty. Captain Balthasar is a star-traveller, and therefore the young lady's kin by association. If Miss Leigh has no objection, I am willing to appoint Captain Balthasar to represent her interests."

Silence hesitated only momentarily. While the men had argued, she had had time to think. Balthasar was an unknown quantity, and it was certain that no man would offer to take on the duties of a guardian unless he thought there was some advantage in it for him. But he was also a star-traveller, part of a world she understood and could manipulate, and a Delian—and a far better choice than anyone else she had seen. She could worry about his motives later. "Your Honor, I accept Captain Balthasar as my guardian."

The judge nodded. "See to it," he said, and the clerk rose to pronounce the formulae. When he was done, and both parties had set their thumbprints to the agreement, Balthasar drew her aside, smiling a vague apology to the judge.

"Quick, was any of that true?" he murmured, still smiling.

"Which?" Silence whispered back.

"What you told them," Balthasar answered.

Silence hesitated, then admitted, "Champuy's never wanted me, just my ship."

"Well, then—"

"No, hold on," Silence said. "Why're you doing this?"

"I suppose you wouldn't believe mere benevolence?" Balthasar asked.

"No," Silence said flatly, old fears stirring. There were worse things than ending up back on Cap Bel—but the man was a fellow star-traveller, she reminded herself, and would follow those codes. At least this way, there was a chance of keeping the ship.

"I need a pilot," Balthasar said quietly, suddenly serious, "and for reasons I can't explain here, it's worth a lot to me to get a woman pilot. You're the first one I've found."

Or at least the first one who was desperate enough to take the job, Silence thought. Sure, there were no female pilots in the Hegemony or, any more, in the Rusadir—it was not explicitly illegal for a woman to hold a pilot's license, but the legal and customary restrictions, particularly the veil, that kept women under some man's tutelage throughout their lives, made it impossible for a woman to meet the licensing requirements. But there were no legal bars to women on the Fringe Worlds and, if custom kept them out of piloting, there was always Misthia. Women ruled on Misthia; women flew Misthia's starships, and no star-traveller was averse to money. If the price were right, he could always hire one of their pilots—though, to be fair, no Misthian liked working for a man. Still, she thought, I don't like the sound of this.

"You'll have to tell me more than that," she said.

Balthasar looked pained. "I can't tell you now, not here," he said. "Look, I don't blame you for not trusting me. I'll do whatever you say I should about your ship, about your grandfather's things. But look what I'm offering. I'll give you a pilot's job, passage from here to Delos guaranteed even if you turn down my other offer, and you can leave the ship there without any other obligation. On Delos, you're bound to find work."

Delos. Black Dolphin had never traded there; the ships that plied the Delian lanes were owned by richer men than Bodua Leigh. But Silence had heard tales of Delos. It was the richest of the non-aligned Fringe Worlds, their unofficial leader—richer even than much of the Hegemony. And Delos was free. She would not have to resort to fictions there. Silence shook her head, an almost unacknowledged dream dying stillborn. She had thought, in the first days after her grandfather's death, of trying to run Dolphin herself, as pilot and owner. But she would never find a crew willing to serve under a woman, especially not on Secasia. She had no choice worth making, except to accept Balthasar's offer.

"All right," she said slowly. "I'll do it."

"Thank you." Balthasar looked over his shoulder at the display globe, and the ship's image frozen in its center. "What do you want done?"

Silence took a last look at the ship she had piloted for nine years, then resolutely looked away. "Sell it—the assessors' price is the absolute minimum, but I doubt you can get much more. The cargo's included in the assessment, so we can forget that. There'll be some debts—field fees and the like—but the money in Grandfather's accounts should cover them."

Balthasar nodded and turned back to the judge. "I beg your pardon, sir. We're ready to proceed."

"I'm glad to hear it, Captain." The judge glanced at his printouts again. "You're prepared to take possession of Bodua Leigh's property—the standard freighter Black Dolphin, her cargo, and the assets currently in accounts held under that name—and to assume responsibility, within the limits of those assets, for any debts legally incurred by Bodua Leigh, all this in the name of Captain Leigh's heir, Silence?"

"Yes, your Honor," Balthasar said.

Silence touched his shoulder. "The debts first."

The captain nodded. "Sir, it's Miss Leigh's—and my—wish that the money in Captain Leigh's accounts should go to pay off his legal debts. Any surplus, of course, should go to Miss Leigh."

"I beg your pardon, Captain," the clerk interjected, "but Captain Leigh's debts were substantial. Even applying the total amount available, over half the debt remains unpaid."

"Let me see that," Silence snapped.

Balthasar caught the printout as it emerged from the clerk's console, and held it while Silence scanned the columns of numbers. There were half a dozen entries of which she knew nothing, repairs and modifications that had never been made, supply purchases that made no sense, contracts that suddenly showed losses instead of profits…. Even her grandfather's haphazard methods should not have produced such strange results. Her confusion was replaced by anger as she read the list of creditors' names. Herlich and Wak; Chandlers; Adelphi Yards; Swirka Company: they were all part of the combine Champuy headed. Champuy's own name was even on the list, and according to the faint printing Bodua Leigh had owed him more than he owed any other single creditor. Silence frowned. She actually remembered that contract, a cargo of rosilk, to be sold on Akra Leuke. They had indeed bought on credit, but had made a decent profit, and had paid off the debt on the return trip. It would have been easy enough for Champuy to change his own records, and the other companies' as well, but the ship's data bank should have shown payments to Champuy, and should have proved that Bodua Leigh never bought any of the other things—

"Uncle Otto," she said aloud.

"What?" Balthasar turned to look at her.

"Uncle Otto. He could sign for Grandfather; he's the one who ran up these debts."

"Can you prove it?" Balthasar asked calmly, too calmly for her liking.

Silence took a deep breath, fought back the urge to strike out at him and at Champuy, to shriek her fury. "No, of course not." It was clear now why Champuy had tried to get himself made her guardian, and why her uncle had failed to appear at the court. Champuy might be owed the largest amount of money, but that did not give him clear title to Black Dolphin if she were sold to pay the creditors. And it would be the ship he was interested in, not just the money—no, she realized, not the ship so much as the ship's fittings, her charts, and most especially the star-books, the collections of pilots' instructions that took the ships from sun to sun. Rusadir star-travellers, free until the absorption from the Hegemony's strict regulations, had always kept better books than the Hegemony's star-travellers were allowed to own. Or was there more to it than that? she wondered suddenly, remembering port gossip. Champuy, it was said, was interested in Earth—interested in the same mercenary way as was her uncle. It looked as though Razil had finally found himself a backer, though she could not tell why the merchant would be willing to go to so much trouble when he could afford to buy another ship for Razil and leave her stranded…. She put that train of thought aside as unprofitable: he was doing it. Well, the joke's on you, Tohon Champuy, she thought. You may get the charts as part of the ship, if I can't get it broken up and that price split among the creditors, but I know there's nothing you can use in them. The star-books are my own property—they're the tools of my office, and that makes them dower-property, and even Hegemonic law can't take them away from me.

"What's the total I owe?" she asked.

"Here." Balthasar pointed to a figure at the bottom of the sheet.

Silence winced. The scrap price she would get if the ship's value were divided among the various creditors would hardly cover that. She would have to sell.

"What's Champuy after?" Balthasar asked. "Your books?"

Silence looked up in surprise. "How—?"

The captain shrugged. "I've seen this kind of trick before. What do you want to do?"

"I don't have much choice, do I?" Silence said bitterly. "See if he'll buy it—but by God he'd better pay the assessors' price—and claim my books as dower property. I'll have to let him have the charts."

"All right." Balthasar turned to the judge. "Your honor, since Captain Leigh turns out to have owed such an unexpectedly large amount, Miss Leigh has asked me to sell the ship, and use that money to pay the various creditors. Her personal—dower—property, which wasn't included in the assessors' survey, of course isn't included in the offer of sale." He glanced at Champuy, his grey eyes suddenly mischievous. "Merchant Champuy had already said he would buy the Dolphin, at yard price. Do I hear a better offer?"

Behind her veil, Silence smiled for the first time that day. It was a petty revenge, but it was a beginning.

"My offer was made under other circumstances," Champuy said warily.

The judge cleared his throat. "Merchant Champuy, your offer was made in open court, and I am compelled to hold you to it. Is there a counteroffer?"

There was an echoing silence in the hall. Clearly, no one was prepared either to challenge the merchant, or to get him out of his current position. The judge's eyebrows twitched, though Silence could not tell if that were a sign of annoyance or amusement. "Very well, the ship is sold. Draw up the papers."

Silence waited while the clerk tapped at his keys, and the machine spat sheet after sheet of paper. Both Balthasar and Champuy signed, then Silence added her thumbprint and accepted Champuy's voucher for the pitiful four hundred Secasian solas that remained after all debts were paid. It would be less than half that amount in the more usual currencies, Delian pounds or Asteriona marks, but she made no outward protest. It would be one more item on Champuy's account, if ever she had the chance for revenge.

"The case of Sumi aBrand," the clerk announced, and Silence started.

"What now?" she asked.

Balthasar made a face. "Let's get out of here," he said roughly. "Then to Dolphin, to get your books. You don't want to have to fight with Champuy after he's already taken possession."

"No," Silence agreed, and followed him from the court.

The Secasian streets were drowning in an afternoon sunlight that bleached all color from the world. The buildings and the people alike had faded to a uniform sandy shade. Only the few women, shrouded as law and custom required in black or dark blue veiling, provided any break in the uniform pale brown. Sweat pearled on Balthasar's harsh-boned face, one drop running down a curious bleached patch of skin on one cheek. Silence reached automatically to push aside her veil, wipe the sweat from her own face, but realized in time where she was. She brushed feebly at the weighted cloth, feeling like a fool, then jammed her hands into the pockets of her coat.

At the edge of the court plaza, a line of cabs was waiting, their domes on the reflective setting to drive off some of the heat. Balthasar tapped on the window of the leader and was rewarded by a sudden clearing of the shell. A mechanical voice spoke from the driver's compartment.

"You wish transport."

A homunculus, Silence thought, and barely restrained a shiver. She had spent most of her adult life in space, where heavy work was done almost exclusively by the homunculi, but she still could not be comfortable in the presence of the quasi-living specimens of a magus's art. They were little more than crudely shaped pseudo-flesh slapped onto a metal skeleton, given rudimentary intelligence and volition, and turned loose to do the dirty jobs no human being wanted. She knew they were useful—necessary, even—but today more than ever, the thought of the caricatured face, like a child's drawing, made her cringe, and she was glad that the part of the dome that covered the driver's section remained reflective.

Balthasar did not seem in the least affected. "Yes, to the port—to the assessors' dock."

"Enter," the homunculus said, and the rear canopy rose slowly. Balthasar scrambled in, and Silence followed more carefully, gathering the skirts of her coat about her. The canopy slid closed again, and the interior fans whined, sending a stronger jet of cooled air into the compartment. Balthasar sighed and leaned back against the seat cushions, eyes closed.

The homunculus droned on. "The meter will run at a standard rate of two bazai each kilometer. Luggage is carried at the rate of three bazai per piece, one las per large parcel or crate…." There was more, but it was dulled by the thrum of the motors as the cab lurched away from the plaza. Silence sighed and loosened the uncomfortable veil, folding back the piece that had covered her nose and mouth. The touch of the air was deliciously cold on her sweating skin.

"So that's what you look like," Balthasar remarked. Silence looked at him, and he quickly changed the subject. "You really think this uncle of yours made a deal with Champuy?"

Silence shrugged, wondering again what the Delian wanted and what price she'd have to pay for this much help. But there was no reason yet not to answer the question honestly. "If Champuy wanted the books, there's plenty he could offer Otto—my uncle's not picky. And that could cause me trouble later, since he's still my legal guardian."

"I forgot that," Balthasar muttered.

Silence said, "The Tabiran law only allows the courts to appoint a temporary guardian in the absence of a male relative. It doesn't give you any permanent rights."

"I see," Balthasar said. There was a speculative look in his eyes, but he did not pursue whatever thought had occurred to him.

Silence watched him out of the corner of her eye, trying to guess what had caught the other's attention. But after that one brief, calculating glance, Balthasar's face closed up, discouraging questions and giving nothing away. Silence looked away again, nervous and dissatisfied. The sooner I find out what's really going on, and what his real price is, the happier I'll be, she thought. And the sooner I have some real bargaining power—however I can get it, even if I have to use my starbooks somehow—the safer I'll feel. But it'll have to be an awfully good offer before I'll take his second job.

The cab slowed then, and they passed through the massive arch that was the gate to the port area. Peering through the darkened dome, Silence could make out the delicate spire of the main control tower, the customs house, and the other administrative buildings clustered at its feet. To either side of them ran rows of the long, low barns that were the docks and tuning sheds and mechanics' workshops. It was remarkable how little those buildings varied from world to world. Only the control tower and its associated complex was ever different.

Beyond the docks was the field itself, a flat expanse of fused earth, linked to the docks by a network of taxiways. A cradled ship waited at the far end of the field, its tow scurrying away toward the bunkers at the edge of the fused strip. As soon as the tow had vanished inside, the ship's harmonium whined to lifting pitch—even two kilometers away, Silence could feel the vibration in the walls of the cab. The ship trembled once, a great shudder that racked it from nose to tail. Then it lifted, rising at first quite slowly, then faster and faster, the gleaming silver of the sounding keel lifting it toward heaven. Silence watched it dwindle until the cab turned into the tunnel that led to the assessors' buildings, and the walls cut off her view.

The cab stopped outside the double doors of the assessors' dock, and Balthasar fed local banknotes into the meter to pop the canopy. The docking bay was almost empty, only two of the twelve spaces surrounded by the durafelt baffles that marked the presence of a ship. There was a small glassed-in cubby just inside the door, and Balthasar approached it confidently.

"Excuse me," he said, tapping on the glass, and a gnomish little man appeared as if by conjuration.

"Yes?"

"We're here to get some things off the Black Dolphin," Balthasar said. "She's been sold, so you won't have her hanging around here much longer."

The watchman looked suspiciously at him. "I'll have to see the papers."

Balthasar handed over the paper authorizing his temporary guardianship, and Silence produced the bill of sale, pointing out the provision that exempted her own belongings. The little man examined each page with excruciating care, but finally nodded.

"All right, I'll let you aboard—but I'll have to come with you. And you can only take things from your cabin, miss. Otherwise I can't know what's yours."

"Fair enough," Silence said, when Balthasar didn't answer.

The watchman led them down the row of empty cradles, past the first baffled ship, whose bow curtain hung open enough to reveal the sharply raked nose of a customs lighter. The unprotected sounding keel showed silver, not the oiled lead of a true keel: it was a local ship, not capable of interstellar travel. There would only be enough Philosopher's Tincture in the metal of the keel to take the ship away from the elemental earth of Secasia's core, not enough to reach purgatory and the stars.

"Silence?" Balthasar called softly, striking a whispery echo from the two keels. "Are you coming?"

Somehow the other two had gotten ahead of her, were already standing on the catwalk that ran along the top of the Dolphin's cradle. Silence hurried to join them, her feet on the rattling stairway drawing a new low thrumming from the keel as she passed. The watchman was waiting at the now-open stern hatch, a rainbow-glittering key in his hand.

"Which is your cabin, miss?"

"This way."

Silence took them down the main corridor that ran the length of the ship to her cabin across the common room from the ladder leading to the lower bridge. The latch clicked open at her touch, and the door slid back. There was not much for her to take: clothes, tapes, trinkets, and jewelry, and finally, from the locked strongbox beneath the mattress in the platform of her bunk, her star-books. They were real books, bound in thin metal, the paper edged with metal as well, to help protect the fragile contents. Charged locks bound covers and pages tightly together, a pinpoint light winking red in the center of each touchplate. She lifted them out of their hiding place, the New Aquarius and the ninety-first edition of the Speculum Astronomi, written in the bastard Latin that had been the magi's first language; then the fussy, much-abused Star-Follower's Handbook, and her copy of the Hegemonic Navy's Topol. One was missing. She frowned, and looked around the cabin again, wondering if she could have left it out on the shelves. But she remembered putting it with the others and locking the box over it.

Balthasar glanced at her and said in an undertone, "What's wrong?"

"My Gilded Stairs. It's not here." Silence frowned more deeply. Only the captain had the master key that would unlock the cabin strongboxes, and she had seen it among her grandfather's effects; Razil could not have stolen it. "Unless Grandfather borrowed it, and left it in his cabin?"

Balthasar nodded once, then cleared his throat. "Was that your bell, watchman?"

"Hm?" The man frowned suspiciously—as well he might, Silence thought disgustedly, that was one of the oldest tricks in the book—but then sighed. "I didn't hear it. You'll have to come with me while I check. I can't leave you aboard alone, you know."

"I'm ready anyway," Silence said.

Balthasar hoisted the larger bag, the one containing the rest of her belongings, to one shoulder. "Is this everything?" he asked. Face and voice were still expressionless, but there was a new tension in his stance.

"All except the books, and I have those," Silence said, and let him precede her from the cabin. The watchman glanced back, but saw only an incompetent woman fumbling with the latch of her carryall. Balthasar was with him, and that was what mattered. Silence held her breath, timing her steps carefully. When the watchman reached the hatch, she was beside her grandfather's cabin, her hand, concealed behind the carryall, fumbling with the latch buttons. She pressed them in the proper sequence, upper left, lower right, lower left and upper right, and then, as the watchman leaned out of the ship to listen, she kicked the opening panel. The door popped open, and she slipped inside. There was no time to look around; the familiar grey binding of the Gilded Stairs stood on the shelves beside the door, and she seized it and swept it into the carryall in one motion. Then she was outside again, the door closing behind her, consumed by the nightmare fear that she had gotten the wrong book after all.

"Sieura Leigh?" That was Balthasar, calling from the hatch. She looked up and saw both men staring at her, the watchman not bothering to hide his annoyance. "The men are here to claim the ship," Balthasar went on.

"Oh?" Silence said, trying to keep her voice level. She glanced down into the carryall, saw the proper title, and hid her sigh of relief. "Then I suppose I'd better hurry." She left the carryall unlatched and walked on to the hatch. Balthasar was still staring at her, one eyebrow slightly raised in question, and she nodded as discreetly as she could.

The captain nodded back. "We'll be off," he said. "You needn't see us all the way out, watchman, we'll be going by the tunnels."

The other man hesitated at the head of the cradle stairs, but shrugged. "Go ahead, Captain. Good voyage."

Balthasar nodded his thanks, then took Silence's arm and hurried her down the cradle stairs and toward the dimly lit tunnel entrance at the far end of the dock. She quickly matched his pace, glancing once over her shoulder toward the main entrance. Sure enough, a group of men were waiting there, their dull coveralls badged with an insignia she could not quite read, but was certainly the mark of Champuy's combine. Champuy himself did not seem to be with them.

"Do you think they'll start trouble?" Silence asked.

"I doubt it," Balthasar said, hauling back the door to the tunnels. "No profit in it—I hope." Despite his words, he glanced nervously over his shoulder at the approaching figures.

Wishing that she knew how to interpret that look—and that her ten-shot heylin were not buried at the very bottom of the carryall—Silence hiked her coat to her knees and hurried down the narrow stairs. Balthasar followed more slowly, his free hand deep in the pocket of his jacket. The fabric bulged with more than just his fist. At the first landing, he paused to listen.

"Well?" Silence asked, after a moment.

"We're clear, I guess. Come on."

The pilot shrugged, biting back her anger, and followed him down the winding stairs.

The area beneath the dock buildings was honeycombed with tunnels, originally intended to give the dock workers some sort of protection from Secasia's baking heat. The star-travellers had taken it over almost immediately, turning it into Secasia's version of the transients' Pale, and expanded the network of tunnels and caverns to include hotels and apartments, recreation areas catering to every conceivable taste, shops and local offices for the giant combines, mechanics' workshops, and even a minor magus's laboratory. Stepping from the secondary tunnels into the main concourse was like stepping into another world, a world far more hospitable than Secasia.

Silence pulled off her veil, stuffing it deep into a pocket, then slipped loose the fastenings of her coat and let it swirl back over the short tunic and sober grey tights she wore beneath it. The cool, machine-scented air of the Pale flowed past her, and she threw back her head to let it stir her close-cropped hair, washing away some of the misery of the past hours. The sight of the colorfully dressed crowd, Oued Tessaans, Rhosoi, Castagi, even a Numluli youth sporting festival ribbons, and the rise and fall of the pure coine of the star lanes calmed her a little. She had lost her ship, but her dream of being pilot-owner of a starship had never been more than that, and an impractical dream besides. She had escaped working for Champuy, or being forced back to Cap Bel—and with a minimum of harassment, despite her sex. She had passage to Delos even without accepting Balthasar's second, dubious offer, and some chance of finding more work. Things could have been worse—

"Silence!" The voice came from one of the hole-in-the-wall bars that filled the shorter side tunnels, and stopped her in her tracks.

"It's my uncle," Silence said involuntarily.

Balthasar made a face. "You can't ignore him now."

"Silence, wait!" The tubby man pushed open the shutters that gave onto the main concourse and clambered out through the empty window frame, ignoring the curses of patrons and passersby.

"Don't you know enough to use the door?" Silence asked.

"I was afraid you'd get away," Otto Razil panted, straightening a jacket that tended to ride up over his paunch. "When is the hearing with Probate?"

"This morning, and you damn well knew it," Silence snapped. Razil was flushed, and the faint, cloying scent of iore, the most expensive of the Ariassan narcotics, clung to his beard. He could rarely afford even the cheap taio on his share of Dolphin's profits, and Silence's anger flared again.

"I'm so sorry," Razil said, slurring his words only a little. "What happened? Did you have to sell the ship?"

Silence took a deep breath. "Yes, I sold Dolphin. It turned out there were some very interesting purchases made on the ship's account that I never saw results of. Do you know how that happened?"

"Your grandfather was always spendthrift," Razil blustered. "I never wanted to trouble you with the financial problems he had—"

"Troubles, hell," Silence said. "You did all the buying, and you altered our records. How much did Champuy pay you for it?"

Razil hesitated, then drew himself up in an attempt at dignity. "If I choose to work for him, that's my business. If you're too stupid to know a good offer—well, I'm not going to let you drag me down with you. Especially when I should be a captain in my own right."

"That's what he offered you? To be Dolphin's captain? Or to go to Earth?"

Razil abandoned all pretense. "Yes, by God, and I'll make it to Earth, now that I've got the backing I need, and there'll be no sharing with some chit of a girl pilot." His expression was momentarily clever. "You're still legally under my power, Silence. I could refuse to let you sign a contract with anyone else, make you come back and pilot for me, let you drool over the five millions and never give you a penny—"

"Shut up," Silence said. She was suddenly consumed with fury, not just at Razil, but at the entire situation. "Listen to me. Law or no law, if you ever try to act as my guardian, if you ever interfere with my life again, I will kill you. Here and now, with my bare hands if I have to. Do you understand me?"

The pudgy man took a step backwards. "Silence, dear girl, no need to be hasty. It's a good job I'm offering."

"No. Now go." Silence reached for the bag Balthasar was carrying, but the captain stepped out of her reach. In the instant her attention was distracted, Razil vanished into the crowd. "Goddamn it, I will kill him!"

"I don't blame you," Balthasar said, "but not here." He nodded at the curious faces around them, the beginning of a crowd of witnesses, and Silence sighed. Her anger faded almost as quickly as it had flared up; she was shaking now with the reaction.

"All right," she said. "But I meant it."

"I know," Balthasar said. "Let's go."

Balthasar's ship was cradled in the fifteenth dock, a long low barn nearly at the end of the row of port buildings. These were the cheaper docks, far from the tuning sheds and the central offices, and were consequently crowded. All but two of the thirty-odd berths were full, and workers were busy preparing those two for new arrivals. It was hot in the dock, especially after the cool of the Pale, and Silence slipped out of the heavy coat. It was the designer's fault for building windows in a dock, she decided, no matter how much it saved the Port Authority on lights. The narrow row of windows that ran around the entire perimeter of the dock, just below the roof beams, showed nothing but Secasia's white-hot sky.

Sun-Treader's cradle was in a berth in the middle of the row. Balthasar lifted a corner of the baffle curtain to let them through, then carefully secured it behind them, shutting out the extraneous noises that might upset the tuning of the keel. Silence stared at the ship. She had been expecting another ship like Black Dolphin, a rounded, fractionally ungainly hull bulging over the edges of a narrow keel. Sun-Treader's hull was long and sleek, not as narrow as a Navy three or four, but still very slim, a streamlined bump on the arrow of the keel. She was clearly built for speed and maneuverability, and Silence's fingers itched for the feel of the controls.

"She's Delian built," Balthasar said casually, but there was a calculating expression in his eyes. "A half-and-half, the yards call that design. She'll only carry about seventy-five mass units—but she's twice as fast as an ordinary freighter."

Silence nodded, following him up the catwalk that clung to the cradle's side. That said a lot about Balthasar, whether he had intended to reveal it or not. A half-and-half just might be a respectable ship on Delos and in the Fringe, but in the Rusadir it was a pirate's ship, at best a smuggler's ship. The cargo space might be limited, but the most valuable illegal cargos tended to be small, and a half-and-half could outrun anything smaller than a Navy five. Just what do you do for a living, Denis Balthasar? she thought, but said nothing, watching Balthasar work the hatch controls.

"Yo, Julie?" Balthasar stepped into the narrow corridor, peered around and upward. "I'm aboard, with a pilot."

"Oh?" A temporary ladder rattled sharply, and a heavily built man dropped through a maintenance hatch into the corridor in front of them. Packing fluid streaked his hands and a few droplets were caught in his untidy beard. He looked momentarily startled to see a woman, but recovered quickly. He removed most of the fluid by dragging his hands across the thighs of his trousers and held out a hand in greeting. "Welcome aboard, pilot."

Silence took his hand speechlessly, overwhelmed by the sheer size of the man. He towered over her by nearly half a meter, his bulk filling the passageway.

"Silence Leigh, Julian Chase Mago, my engineer," Balthasar said. "Silence has signed on at least to Delos."

"Oh?" Chase Mago looked down at his captain, over Silence's head. "So she's going to—"

"We haven't discussed that," Balthasar cut in quickly. The engineer shook his head.

"That reminds me," Silence said. "What was this deal you couldn't talk about at the court?"

"Let's drop your things in the pilot's cabin," Balthasar said. "Then we'll talk."

The half-and-half's construction was very different from that of a standard freighter, and the differences made Silence wonder again just what kind of cargos Balthasar carried. The main hatch opened not onto the main deck but into a short length of corridor running between the two main holds. A ladder led up to the crew deck, directly into a common room that was little more than a broader section of corridor fitted with a few battered pieces of furniture. A bank of automatic kitchen machines stood against one bulkhead, separated from the rest of the common area by a woven metal partition. Silence could see grooves in the floor where other partitions could be fitted to create at least two more cabins.

The pilot's cabin was right up in the bow, at the base of the ladder that led to the double bridge. It was oddly shaped, almost triangular, but the fittings were fairly standard. Bunk and monitor console were built into opposite bulkheads, and a shower compartment was tucked into the apex of the triangle.

"I know it looks like you're right over the keel," Chase Mago said, "but you've got about a meter of packing in between. You shouldn't feel a thing."

Silence nodded and tossed the smaller carryall onto the bare mattress of the bunk. Balthasar set the larger bag just inside the door and turned to go.

"I'm fixing tea," he said. "Do you want some, Silence?"

"Please."

The door slid shut automatically behind him, and Silence stared at the empty cabin. Bare walls, bare bunk, darkened console… suddenly all the practical difficulties of starting over, of imposing her will on a new ship and fitting into a new unit, threatened to overwhelm her. "Is there anything I can do to help?" Chase Mago asked.

"No, thanks, I'll settle things later," Silence answered. Then at last the cadence of his speech registered. "You're from the Rusadir, aren't you?"

The engineer hesitated briefly, then said, "Yes, from Kesse."

Silence looked up quickly, the trivial question of mutual acquaintance dying on her lips. Kesse—renamed Tarraco by the Hegemony in an attempt to wipe out the memory of the planet's resistance—had been the last of the Rusadir worlds to fall to the invaders. It had lasted for a year under siege, had turned back all the tricks the magi had thrown against it. Only the treachery of a splinter faction of its oligarchs had forced the planet to surrender. The survivors had been forcibly relocated and subjected to harsh sanctions—among which, if she remembered correctly, was a ban on star travel.

Chase Mago shrugged, reading the question in her eyes. "Lots of things are possible if you pay off the right people. And we don't go very deep into the Hegemony if we can help it…. I think the tea's ready now."

Silence nodded, oddly embarrassed, and followed the engineer out of the cabin. The smoky aroma of the tea filled the commons. Chase Mago sniffed at it, then dropped heavily into a folded cushion chair that bore the permanent imprint of his huge frame. A hammock chair stood by the dented table, the paint worn from its metal frame by constant use; it was obviously Balthasar's favorite. There was a third chair as well, an oil-inflated armchair whose undented cushion proved it had only recently been taken from storage. Silence drew it closer to the table and settled herself cautiously against the still, chill padding. Balthasar emerged from the galley cubicle with three large mugs balanced on a tray, and Silence accepted one blindly, sipping at the steaming liquid.

For the first time in days, in the weeks since her grandfather's death, she had the time to think of her own feelings, and she winced, expecting the familiar tide of grief and anger. But there was only exhaustion, a numbing fatigue and a sense of being out of place. There had been so much fighting, and not much to show for it, really—only this strange ship and its equally strange crew.

"Do you want to talk?" Balthasar asked.

"No," Silence said, rising so quickly that she almost spilled her tea. "Not now. I'm dead tired, and I want some sleep before I have to make any decisions."

"Sure," Balthasar said, and Chase Mago nodded. Their eyes flickered toward each other in almost subliminal conversation, but Silence had no interest in reading it. She retreated to her cabin, closed and latched the door behind her. She stooped for the bag that held her bedding, but lost her balance and stumbled back against the bunk. The mattress was positively seductive in its Spartan comfort, and she let herself lean back against the pillow. In just a minute, she promised herself, in just a minute I'll get up, make the bed. In just a minute. And then she slept.