Karen Joy Fowler is the author of six novels and three short story collections. She's written literary, contemporary, historical, and science fiction. Her most recent novel, We are all completely beside ourselves, won the 2013 PEN/Faulkner, the California Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Man Booker in 2014. She lives in Santa Cruz, California.

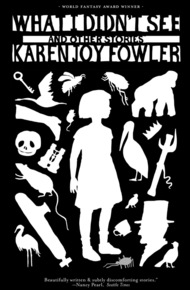

WHAT I DIDN'T SEE was first published by Small Beer Press in 2010. According to the Library Journal, the stories in it are an eclectic mix, characterized by obsession, disappearance, and revelation. It won the World Fantasy award in 2011.

Whether Karen is portraying a modern rebellious teenager sent by her parents to a horrifying camp for juvenile delinquents, a turn-of-the-century photographer taking pictures of relics found at an archeological dig, or a midcentury woman sent on a safari to hunt gorillas in Africa, you the reader may be sure she will delve deeply into her characters' hearts and minds, reveal unexpected thoughts and feelings, and spin unusual plots supported by meticulous research and extrapolation. Enjoy this award-winning collection by this bestselling author in The Story Collection StoryBundle. – Lisa Mason

"An exceptionally versatile author . . . Fowler has "the best possible combination of imagination and pragmatism," as she applies unique narratives into carefully crafted structures."

– St. Louis Post-Dispatch"In all these stories, Fowler ("Sarah Canary," "The Jane Austen Book Club") delights in luring her readers from the walks of ordinary life into darker, more fantastical realms. There, as one of her characters remarks, "Your eyes no longer impose any limit on the things you can see." . . . Fowler's closing story, "King Rat," is a masterpiece. Reading more like a personal essay than fiction, it pays eloquent tribute to "the two men I credit with making me a writer." Here's a volume that serves as a fine introduction to Fowler, if you haven't come across her before—and one that will deeply satisfy fans who've been with her from the beginning."

– Seattle Times"One of those writers who can write an almost thoroughly mainstream realistic story and nearly convince us we're reading SF, or write and SF story and convince us we're reading mainstream realism."

– Locus"That rare writer who can match the power of her novels with the power of her short stories. She works in the world of myth with great ease. We feel, reading her stories, that we are in our world, but some portion of it that connects vitally with everything else. What happens here is gripping, important, compelling, and often terrifying. Her new collection of stories, 'What I Didn't See' offers readers perfect renderings of a New American Mythos"

– Rick Kleffel, The Agony Column"Karen Joy Fowler takes the short story in directions readers could never anticipate, and her latest collection from the wonderful Small Beer Press, What I Didn't See: Stories, offers up numerous delights for the smart and creative reader. From the wham-bang start of "The Pelican Bar" to the Hemingway-esque title story, Fowler takes you from the past to the future in stories that feature speculative fiction elements, or are starkly true to life. Cast your preconceived notions aside and settle in to explore the human mysteries Fowler mines with abandon. This is literature at its most intriguing, and a reminder of how bold and daring a gifted writer can be."

– Colleen Mondor, Bookslut"The practicality of her views is what makes them upsetting, a reminder how tragedies great and small affect people everyday even if we aren't privy to them. And that is where Fowler succeeds — even if her brutal boarding houses or Congolese misadventures aren't real to us, post-traumatic stress disorder is. All of her narrators are survivors, and they tell their stories in blunt, practical ways we imagine they need to protect themselves."

– For Books’ Sakes"Fowler cements her place in fiction history–genre or otherwise–not because of her fancy tricks but through sheer technique and her excellence in characterization."

– Charles Tan, Bibliophile StalkerHow I Got Here:

I was seventeen years old when I heard the good news from Wilt Loomis who had it straight from Brother Porter himself. Wilt was so excited he was ready to drive to the city of Always that very night. Back then I just wanted to be anywhere Wilt was. So we packed up.

Always had two openings and these were going for five thousand apiece, but Wilt had already talked to Brother Porter who said, seeing as it was Wilt, who was good with cars, he'd take twenty-five hundred down and give us another three years to come up with the other twenty-five, and let that money cover us both. You average that five thousand, Wilt told me, over the infinite length of your life and it worked out to almost nothing a year. Not exactly nothing, but as close to nothing as you could get without getting to nothing. It was too good a deal to pass up. They were practically paying us.

My stepfather was drinking again and it looked less and less like I was going to graduate high school. Mother was just as glad to have me out of the house and harm's way. She did give me some advice. You can always tell a cult from a religion, she said, because a cult is just a set of rules that lets certain men get laid.

And then she told me not to get pregnant, which I could have taken as a shot across the bow, her new way of saying her life would have been so much better without me, but I chose not to. Already I was taking the long view.

The city of Always was a lively place then – this was back in 1938 – part commune and part roadside attraction, set down in the Santa Cruz mountains with the redwoods all around. It used to rain all winter and be damp all summer, too. Slug weather for those big yellow slugs you never saw anywhere but Santa Cruz. Out in the woods it smelled like bay leaves.

The old Santa Cruz Highway snaked through and the two blocks right on that road were the part open to the public. People would stop there for a soda – Brother Porter used to brag that he'd invented Hawaiian Punch, though the recipe had been stolen by some gang in Fresno who took the credit for it – and to look us over, whisper about us on their way to the beach. We offered penny peep shows for the adults, because Brother Porter said you ought know what sin was before you abjured it, and a row of wooden Santa Claus statues for the kids. In our heyday we had fourteen gas pumps to take care of all the gawkers.

Brother Porter founded Always in the early twenties, and most of the other residents were already old when I arrived. That made sense, I guess, that they'd be the ones to feel the urgency, but I didn't expect it and I wasn't pleased. Wilt was twenty-five when we first went to Always. Of course, that too seemed old to me then.

The bed I got had just been vacated by a thirty-two-year-old woman named Maddie Beckinger. Maddie was real pretty. She'd just filed a suit against Brother Porter alleging that he'd promised to star her in a movie called The Perfect Woman, and when it opened she was supposed to fly to Rome in a replica of the Spirit of St. Louis, only this plane would be called the Spirit of Love. She said in her suit that she'd always been more interested in being a movie star than in living forever. Who, she asked, was more immortal than Marlene Dietrich? Brother Porter hated it when we got dragged into the courts, but, as I was to learn, it did keep happening. Lawyers are forever, Brother Porter used to say.