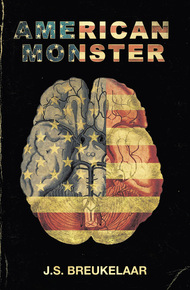

J.S. Breukelaar is the author of Collision: Stories, a 2019 Shirley Jackson Award finalist, and winner of the 2019 Aurealis and Ditmar Awards. Previous novels include Aletheia and American Monster. Her short fiction has appeared in the Dark Magazine, Tiny Nightmares, Black Static, Gamut, Unnerving, Lightspeed, Lamplight, Juked, in Year's Best Horror and Fantasy 2019 and elsewhere. She currently lives in Sydney, Australia, where she teaches writing and literature, and is at work on a new collection of short stories

In the beginning, KALI I8 created Norma (a network operation requiring minimal access) with a singular goal: bring back the horn of the perfect male.

Spill City: the coast of a near-future California, newly broken from the continental United States. In a temporary calm between storms, Norma combs the exposed intestines of the human world for the Guy. The Guy, the horn, is the only way home. If home exists. If home ever existed.

The longer Norma stays, the harder it is to remember.

She is a woman, a mother, a harbinger, a vessel, a tool, a program. She can be written and unwritten over and over again until something, someone, sticks.

And people, humans, are starting to stick.

Mommy is not pleased.

"American Monster is, in a way, the great lost American novel everybody's looking for, except it died long ago and has come back as a winged demon."

– Seb Doubinsky, Weird Fiction Review"American Monster is a tour de force in dystopia seen through the eyes of an alien who's more human than most humans. Breukelaar's ability to range at will with the subtlety of a pickpocket through cascading elisions of register, tone, style, and mode is astonishing. On page 109 alone, we get the tactics and tone of the perennial novel, the intimacy of confessional poetry, the riffing of the Beat, inside jokes, cultural allusions famous and obscure, argot, sci-fi peculiarity, profanity, porn, bizarro fucked-upedness, and more. Throughout the book, which, not incidentally, navigates modes of natural, scientific, and travel writing better than anyone I've read since Cormac McCarthy—and here I'm thinking specifically of Blood Meridian—we're treated to a true cornucopia of influence and style appropriated and converted to her own, among them such lights as H.P. Lovecraft, Philip K. Dick, J.G. Ballard, Ursula K. Le Guin, Charles Bukowski, and Michel Houellebecq."

– D. Foy, author of Made to Break"The closest a book's come to Samuel R Delany's Dhalgren probably ever. Breukelaar is one of the best new writers around and I can't wait for whatever comes next. Read this book. There's really nothing else like it."

– Edward J. Rathke, The Best Indie Press Books I've Ever ReadA woman and a child moving through the mean streets, nothing that hadn't been seen before. It would be light soon. Norma's shadow fell over the mouth of an alleyway—a Consortium guard's knuckles tightened over the butt of his rifle but he relaxed when he saw the child. Norma had managed to get her cleaned up so that her cruddy parka she blended in, her pallor, the hunger in her eyes reflected in a thousand other faces, untold other eyes. All around them, the persistent swoosh of skateboard wheels, the clack of cowboy boots, black hat brims, and Norma wheeled wildly to and fro but there was nothing else. Around them nothing but the space of darkness, the space of fear.

Raye was talked out. But as they neared the Sanctuary, she said, expressionless, 'Leeks.'

The sour, overcooked reek of whatever seethed in the Sanctuary Crock-Pot had drifted down to the street and Raye picked it up a block before Norma did. At the door to the shelter Norma gave the kid a couple of Ambiens and left her there without making eye contact. Without saying goodbye.

Norma jumped a GMC recombo with Tijuana plates and flew off at the trailer park. She landed badly and splashed in some standing water at the edge of the road. Her arms flailed as she regained her balance. By the time she got to the trailer, numb with exhaustion, all she could do was kick off her boots and fall face-down on the cot. Her eyes burned yet she couldn't sleep. She dry-swallowed some off-market triazolam but it didn't help. She went outside, wondered if she should go down to the beach. And then what? Take a dip? Plunge into the slick, blood-red with nitrates and watch her precious skin turn to cottage cheese?

Mommy said, 'A daemon cannot die.'

If that is what she was once, what was she now? She'd adopted a street kid, longed for a man she couldn't have, and suffered from killer PMS. What was that? There was no way of knowing.

The wind was bitter and the ocean was a roiling hole. And also a whole. Mirror of the world, source of all its pain, all its life and time. She saw it in its entirety. All the way down, two-three-four miles. The trick was getting back up. A daemon couldn't die but how far could a woman fall? How many miles to mortality, Mommy? Are we there yet?

Dawn touched the fleshy cliffs. Their tufted vegetation rippled like living pelt. Eroded monsters, doomed gorillas with slumped and leathery bodies swathed in mist. The path beneath her feet was lined with wrappers, cans and burger boxes in various states of decay. An odor of petals, pine and sweet corrosives. She put her hands on the wooden rail at the edge overlooking the beach. The countless hands and unending seasons that had touched this rail—she thought of them and felt the call of the unfathomed sea—find out what you truly are.

Norma could see beneath the surface of the water, see it in its entirety. The whole. Float through it in her mind—the sand bars and buried reefs, the shipwrecks and underwater crevasses. She could see the other side. Not just San Diego Bay but beyond. To where the Pacific grew warm, where warships lay buried along with the odd asteroid chunk, ancient fuselage, and then grew cold again. And the life it sustained—would it take her? Would it want her? Mommy said no. So what had changed? Norma could feel it. She needed to know. What was she now?

She needed to know if she could die.

The way the Michael Jackson guy's eyes had darkened at the end, just before they'd brightened. Like it had gotten crowded in there. Is death what they'd seen in her, those crowded eyes? Or not. Had they seen the Silence?

Because that's who she was. Mommy had made her that way, a conduit. A hole to nowhere. She could only hope that something had broken through the silence.

Bring bring.

Norma released her clawed hold on the wooden rail. She brushed off the sand and splinters and went back in the trailer and lay on the bed with the curtains open to the numberless stars. She carried the inevitability of her fall—there was blood on her hands and she didn't know why—within her, the dentata sharpening its teeth. The longer she waited before implantation, the worse the pain.

'Look,' she said, 'Here I am.'

The sun had gotten too big for Mommy, gave it a swollen head, or was it the other way around? Who had killed who? What had killed the First Beings? The fissioning death star, or the hostile, doomed Brainworld determined to take its beautiful horned children down with it? If Mommy couldn't have the beautiful First Beings, nothing could. It made sure of that, but to learn its power, had it summoned them or created them?

It was impossible to know, impossible not to know.

There were footsteps outside the trailer, a faint whiff of straw and manure as if stuck to the soles of a shoe. She, the hunted now, haunted by some Guy with shit on his shoes. What was he? Her skin prickled and the darkness nailed her to the bed. The shuffling footsteps receded. What was its name? She went to a barn in her dreams and came back with blood on her hands, more fallout? Or psychosomatic guilt over sins unnumbered and truths debowelled—was this guilt another side-effect of the mission? Because that guilt thing really blowed. And however it had originally been conceived the mission had changed. Elvis has left the building Mommy and the truth is dead even as it is created. Brrring brrring.

'I am never going home.'

Sleep. Slipping over the lip of a waking dream, she felt, more than heard, a song at the horizon, so beautiful it finally made her smile. A stranger singing—the Guy?—calling to her, pulling her toward the song, his image on the rise, a gelid moon that became the face of Michael Jackson and Mac Daddy and then the guy on the train with the fulvous eyes. Gloria, the song went. GEE-EL-OH-AR-I-AY. A phone rang. And rang. Irretrievable beginnings, unpredictable ends, her curse was to have been made in the image of no other. Was it a puppy? Or a child? Did the daughter pass on? Or live to rip out the heart of its parent? To write a letter from Neverland, miles between us, Michael Jackson. Time against us. Call home, hun. Chewy yeah, and crusty too. Looks like gum. Or was that cum? One two I'm coming for you. Make Mommy talk. This is God, said the wolf man, reaching into Norma's hole and pulling out a plum. I'm your boyfriend now.