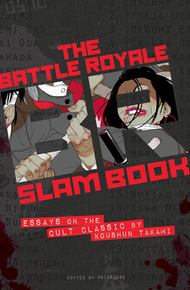

Edited by Haikasoru: Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington

Nick Mamatas is an editor for Haikasoru, an imprint dedicated to Japanese science fiction, fantasy, and horror in translation. Masumi Washington is Haikasoru's editor-in-chief.

Koushun Takami's Battle Royale is an international best seller, the basis of the cult film, and the inspiration for a popular manga. And fifteen years after its initial release, Battle Royale remains a controversial pop culture phenomenon.

Join New York Times best-selling author John Skipp, Batman screenwriter Sam Hamm, Philip K. Dick Award-nominated novelist Toh EnJoe, and an array of writers, scholars, and fans in discussing girl power, firepower, professional wrestling, bad movies, the survival chances of Hollywood's leading teen icons in a battle royale, and so much more!

"Anyone who has experienced Battle Royale and/or its adaptations will find that The Battle Royale Slam Book is a collection of insightful essays. Even those who normally don't read essays will find the essays here worth reading."

– Leroy Douresseaux, editor and reviewer for The Comic Book Bin"From the impact of teen sexuality to feminism to how Home Alone functions as a Battle Royale-style horror film, this book is full of ideas and interpretations that will make you think differently, or at least more deeply, about Takami's classic work."

– Rebecca Silverman, reviewer for Anime News Network"Whether you are a fan of the novel/movie/manga or someone who likes analysis of books and movies, this is a great book, that provides a deeper look at the Battle Royale phenomenon."

– Erik, Amazon reviewOh, kids. They grow up so fast. Unless somebody kills them. Or they kill each other.

It's only natural to want to protect them, of course. And not just their lives, but their innocence. That said, life is what happens when we're making other plans. And death shows up whenever, and for whomever, the fuck it wants.

Speaking personally: I saw my first dying people within half an hour of landing at Ministro Pistarini International Airport, just outside Buenos Aires. It was 1966, and I was eight years old.

We'd just taken a Boeing 707—the largest craft in the fleet of Aerolineas Argentinas—from Washington, D.C., care of the US State Department. My dad's mysterious new government job had brought the family from Milwaukee to Arlington, VA, for six months of prep, before launching us deep into the other America.

I have jumbled memories of landing and negotiating customs, lugging our baggage as we followed the guy with the driver's cap and the sign marked skipp to the sleek sedan taking us to our new home. All I can say for sure is that I had the window seat in the back, on the driver's side—and that we were less than ten minutes down the Richerri Motorway—when I saw the cloud of dirt and rock from the edge of the overpass ahead.

There was a bus, hurtling sideways and over the brink, like a train derailed. I couldn't see the shattering glass, but I could see the screaming faces. Blood on some, poking through the broken windows. Others pressed against the glass as yet remaining.

Then we were under the overpass, me whipping backward in my seat to watch the bus plummet downward, then disappear from view. Our driver did not slow for a second.

That was my first genuine childhood glimpse.

Once we settled in the suburb of San Isidro, in a very nice two-story house with a swimming pool and bars on the windows, I began to explore. Making friends with the local kids and learning Spanish a trillion times faster than the rest of my family combined. The neighborhood boys kicked my ass at futbol until I got the gist of the game and earned their respect. At which point, they started showing me the ropes.

It was a fifteen-block walk from my house to the San Isidro station. From there, I took the commuter train three stops to La Lucila, where El Colegio Lincoln was, the school for US government, military, or corporate kids, as well as wealthy Anglo-Argentinos.

About three blocks along the way, there was a car full of dried blood and bullet holes, pulled up at the curb right next to a local bodega. I was informed that it had belonged to a couple of local fuck-ups who thought that robbing a bank might be a good idea.

At that time in Buenos Aires, even traffic cops carried submachine guns—one of the perks of a police state. And they had totally Bonnie and Clyde-ed that car, swiss-cheesing it with hundreds of rounds that I spent countless hours, in youthful awe, cataloging.

So if that bullet went through the door here, I noted, peering through the metal hole, that explains that gouge in the driver's seat and this splash of blood on the rear upholstery. Whereas these seven holes sawed right across the side, on either side. So which was the entry, and which was the exit? A forensic pathologist at the age of eight.

That car was left sitting at the curb for nearly a year, as a constant reminder that if you messed with them—if you robbed a bank—they would kill the living shit out of you. The urban equivalent of a head on a medieval pike.

But it didn't fully occur to me that little kids could die like that until I watched two ten-year-olds beat a six-year-old to death on the San Isidro train platform, from the other side of the tracks.

The six-year-old was a beautiful boy. Very popular with the Americans, whose shoes he shined as they waited for the train. He could barely lug his wooden shoeshine box, tiny as he was. But people loved him for that: an adorable novelty with a keepsake smile. Like a luminous virgin on shoeshine prostitution row.

One morning, it just became too much for the competition. They beat his brains in, then out of his skull, with his own shoeshine box. Then ran off. I never saw them again.

But I saw what happened.

Not too long after that, I found Lord of the Flies in the school library. And it, more than anything, helped me process what I was seeing all around me. I kept coming back to the death of Simon, his body floating in the water. And poor Piggy, as both his skull and the conch that signified civilization were shattered.

This, I realized, was what happened when we lost our way.

Over the next four years, I bore witness to a lot more blood and death. Saw futbol stadium staircases stream with the blood of trampled hundreds on my tenth birthday. Saw Chilean immigrants beaten by armed police right outside my school fence, during lunchtime recess. Ultimately fled the country, running down the street with screaming thousands as armored tanks rolled down the central boulevard, en route to overthrowing Presidente Ongania. Barely got out of the country in time to miss the Generalisimo of the Month Club, and the Black Hand, and the thousands more who wound up disappeared, their mass graves only discovered decades later.

In short, I saw far more horror at an early age than any young man should.

But I learned a hell of a lot.