Melissa Scott is from Little Rock, Arkansas, and studied history at Harvard College and Brandeis University, where she earned her PhD in the Comparative History program. She is the author of more than thirty original science fiction and fantasy novels, most with queer themes and characters, as well as authorized tie-ins for Star Trek: DS9, Star Trek: Voyager, Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis, and Star Wars Rebels. She won Lambda Literary Awards for Trouble and Her Friends, Shadow Man, Point of Dreams (written with her late partner, Lisa A. Barnett), and Death by Silver, written with Amy Griswold. She also won Spectrum Awards for Shadow Man, Fairs' Point, Death By Silver, and for the short story "The Rocky Side of the Sky" (Periphery, Lethe Press) as well as the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. She was also shortlisted for the Otherwise (Tiptree) Award and the Midwest Book Awards. Her latest short story, "Sirens," appeared in the collection Retellings of the Inland Seas, and her text-based game for Choice of Games, A Player's Heart, came out in 2020. Her solo novels, The Master of Samar (2023) and Fallen (2023) are both available from Candlemark & Gleam. Website.

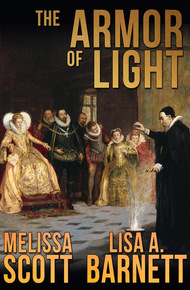

Lisa A. Barnett was born and raised in Dorchester, Massachusetts, attended Girls' Latin School, and received her BA from the University of Massachusetts/Boston. She began working in theatre publishing while she was still in college, beginning at Baker's Plays in Boston, and then moving to Heinemann, where she developed her own line of theatre books. In that role, she edited plays, monologue collections, and books of practical theatre, as well as a second line of books on theatre in education, which included a string of award-winning titles. As a writer, she worked primarily in collaboration with her partner, Melissa Scott, and together they produced three novels: The Armor of Light, set in an alternate Elizabethan England, Point of Hopes, and Point of Dreams, the last a Lambda Literary Award Winner. They also produced a short story, "The Carmen Miranda Gambit," which was published in the 1990 collection Carmen Miranda's Ghost is Haunting Space Station Three. Outside of the collaboration, she had a pair of monologues published in the collection Monologues from the Road, and subsequently saw them produced as part of an evening of "theatre from the road." She was exceedingly fond of both dogs and horses, and was an active member of the Piscataqua Obedience Club as well as being heavily involved in several equine rescue organizations. She was diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer in 2003, and died of a metastatic brain tumor in 2006.

The heavy summer air of 1595 is full of portents for Elizabeth, England's Queen, and James VI, King of Scotland. A coven of witches secretly controlled by the Wizard Earl of Bothwell has summoned a storm to sink the ship that bears James' bride to Scotland. Though the ship made port, the success of their summoning has emboldened them; the coven is now launching wizardly attacks on the King himself — and James is terrified.

But this is not quite the England that we know. The Queen's champion Sir Philip Sidney did not die at Zutphen, nor was poet and spy Christopher Marlowe murdered in a Deptford tavern, and both are powerful magicians, if in different traditions. The Queen must send them north to break the prophecy and save the King of Scots — and England's future.

Almost thirty years ago, Lisa Barnett and I each had an idea for an Elizabethan fantasy, and neither one of us would cede the topic to the other. Instead, we combined the two stories, and came up with a better idea than either one of us had had alone: an alternate history, in which neither Sir Philip Sidney nor Christopher Marlowe died as they did in our world, and in which magic works exactly as the Elizabethans believed it did. I'm still really proud of this one. – Melissa Scott

"This is a good historical fantasy. They played around with the history, saving Sidney from his Dutch wound and Marlowe from his tavern in Deptford, and punched up the magic a lot. Marlowe would have loved that. What's more, they got the language right, they got the characters right, they got the society right, they sure as hell got the clothes right. It's set up like a play, in five sections, and each section does exactly the right thing. Sidney would have approved of it. Robert Greene would have given it a rave review. Cecil would probably have had them both silenced."

– Delia Sherman"For any student of English literature or fan of Shakespeare, Sidney, or Marlowe, this book is a dream come true. What happens in The Armor of Light is what should have happened."

– Pamela Dean"That this is alternate history doesn't really matter to the story: this tale of intrigue, magical plot and mundane counterplot would be worth reading if set entirely in a fictitious pseudo-England."

– Locus"Historical accuracy and historical invention, society and culture, detail of dress and costume, drama and action, all are highlighted in The Armor of Light. Ellen Kushner gave me a copy of the original edition years ago and told me then what a great book it is. And it is. It's one of the best fantasy novels of the 1980s, and worth a serious re-read now."

– David G. Hartwell"The novel has a well-researched feel to it… yet there are more than enough sword fights and fireworks to satisfy less intellectual tastes."

– Dragon MagazineChapter One

The trivial prophecy, which I heard when I was a child and Queen Elizabeth was in the flower of her years, was

When hempe is sponne

England's donne:

whereby it was generally conceived that after the princes had reigned which had the principial letters of that word hempe (which were Henry, Edward, Mary, Philip, and Elizabeth) England should come to utter confusion....

Francis Bacon, Of Prophecies

She had put away mirrors some years before, preferring to see herself reflected in the words of the young men who still thronged her court. Even now, she paused in the doorway, giving the two old men who waited for her time to see and admire and frame their compliments. The cool morning light that streamed through the diamond-paned windows would not flatter, and a part of her knew it and rejected it, even as she sailed forward to accept their homage.

"Spirit," she said, with real fondness, and one old man—he was seventy-five this spring, had seen three quarters of a century—bowed stiffly back. He was bundled in his robes of office, fur-lined gown pulled close about his throat beneath the narrow ruff, long jerkin buttoned close, the flaps of his wool coif pulled over his ears even in springtime. The woman, resplendent in white figured satin that showed a vast expanse of white-powdered bosom, rejoiced that she had not succumbed to that frailty of old age. "Dr. Dee." Despite herself, her voice sharpened on the name, as she stared at the second old man in his scholar's black. There was something of the crow about him, something of the ravens that haunted the Tower, despite his protestations that he used only white magic, and never more so than today. Perhaps he sensed her unease, for his bow was very deep, and he blinked weak eyes nervously at her as he straightened.

"Your Majesty." It was Burleigh who spoke first, secure in his monarch's favor—the only man now living who could make that boast. "I am very grateful that your grace has agreed to this interview."

That was more of a barb than most men were allowed, considering how strenuously the queen had resisted seeing her court wizard of late. Elizabeth's thin lips tightened further, wrinkles showing momentarily in the thick paint, and then she had smoothed her expression, seating herself carefully in her chair of state. The immense white skirt, sewn with silver and pearls and scattered with blood-red roses, pooled around her ankles, hiding her embroidered slippers; she rested her beautiful long hands on the arms of the chair, displaying them in a pose so practiced it had become natural. The rising sun shone through the upper coils of her immense red wig, glinted from the crown set precariously atop that pearl-strewn edifice. Her face, as she had intended, was in shadow.

"Well, Doctor Dee," she said, and heard herself sharp and shrewish, "what news have you brought me?" The old scholar—he was only six years older than she, though she chose to forget it—blinked rheumy eyes at her again, and she frowned. "Does the daylight trouble you, master wizard? We will have the shutters closed."

Burleigh frowned, the thickets of his eyebrows drawing down toward his beard. Dee said, stammering slightly, "I beg your Majesty's pardon. It's not the light but your Majesty's presence that dazzles me."

"We could withdraw that as well," Elizabeth said, but her expression softened slightly. It was a feeble compliment, and delivered without courtly graces, but, she thought, sincere enough. She leaned back in the high chair, easing bones that woke tired now after a night's dancing. "Come, sir, my dear Spirit says your news is both urgent and alarming. Let's hear it—it may not be so fearsome in the sunlight."

The wizard bowed again, and thrust his gnarled hands into the furred sleeves of his gown to hide their shaking. The room was chill, one of the long windows opened to let in the cool spring air, but it was not only the cold that made him tremble. "As your Majesty—and his lordship—know," he began, "at the new year I cast your Majesty's horoscope for England, and share those tidings with your Majesty alone."

The queen's eyes slid toward Burleigh, and were answered by an infinitesimal nod: a royal horoscope was more than a matter for private concern; could become, in the wrong hands, a matter of state. Dee was well guarded while he served the queen, in part to protect him from the mob who feared him and had once burned his library, but those guards were also there to assure that no state secrets, however obtained, made their way into the hands of Elizabeth's enemies. If Dee saw the movements, he gave no sign of it, but continued in his soft, stammering voice, "At this new year, as my lord Burleigh has doubtless told you, the heavens were troubled, the portents strange, and I could read no certainty of anything in stars or glass. In such a case, the best remedy is delay, and I did delay, until the—storm—seemed past." He glanced up, anxiously, but could read nothing in the queen's shadowed face. Burleigh stroked his beard, weighing every word.

Dee bowed his head again. "Then, at your Majesty's express command, I cast the horoscope. The portents were —well, ominous, your Majesty."

There was a long silence, and then Elizabeth said, "Ominous, Doctor Dee? Could you perhaps be more specific in your terms?"

Recognizing the tone, Dee gave Burleigh a swift glance of appeal. The secretary of state said, slowly, "Yes, your Majesty. The signs concern what will befall England after your death."