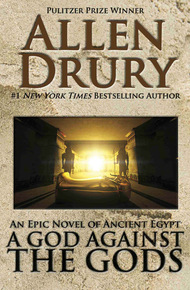

Allen Drury is a master of political fiction, #1 New York Times bestseller and Pulitzer Prize winner, best known for the landmark novel Advise and Consent. A 1939 graduate of Stanford University, Allen Drury wrote for and became editor of two local California newspapers. While visiting Washington, DC, in 1943 he was hired by the United Press (UPI) and covered the Senate during the latter half of World War II. After the war he wrote for other prominent publications before joining the New York Times' Washington Bureau, where he worked through most of the 1950s. After the success of Advise and Consent, he left journalism to write full time. He published twenty novels and five works of non-fiction, many of them best sellers. WordFire Press will be reissuing the majority of his works.

The sweeping chronicle of a great and tragic pharaoh who lost his throne for the love of a God.

In the glory of ancient Egypt, an epic of a royal family divided, bloody power ploys, and religious wars that nearly tore apart one of the greatest empires in human history.

AKHENATEN: The dream-filled King of Egypt, who dared to challenge the ancient order of his people and dethrone the jealous deities of his land for the glory of one almighty God.

NEFERTITI: The most beautiful woman in the world, bred from birth to be the Pharaoh's devoted lover—and to follow him anywhere, even in his tortured obsessions.

If you know the name Allen Drury, your next reaction will be "What is he doing in an epic fantasy bundle?" Drury, best known for the political masterpiece ADVISE AND CONSENT, published two ambitious historical novels set in ancient Egypt. When they were first released, many critics asked the same question, because the shift from Washington DC to the Nile seemed so strange. His response was "Politics is politics, regardless of the setting." – Kevin J. Anderson

"Drury's best book"

– Fort Worth Star TelegramBook I

Birth Of A God

1392 B.C

Kaires

I am Kaires, as men properly say Kah-ee-race, named by my father, after he brought me finally from my birthplace to his beloved city of Thebes, for the great scribe Kaires who lived during the time among men of the God Nefer-Ka-Ra (life, health, prosperity!) of the House of Memphis, one thousand five hundred years ago.

I, also a scribe, write this in the twenty-second year among men of the God Amonhotep III (life, health, prosperity!) of the House of Thebes. Even do I live in his house itself, in the Palace of Malkata, for I am young, well favored and, I think, intelligent; and such are needed for the governing of the empire of the Two Kingdoms that stretches now south to the Fourth Cataract of the River Nile, north beyond Syria to the land of Mittani, and east and west to the Mountains of Light beyond which the Red Land begins and only the wretched Crossers of the Sands dare go.

Together with my friend Amonhotep the Scribe (he who comes of humbler birth and a father named Hapu, both of which he flaunts from time to time when surrounded by the scions of noble houses who find themselves unequipped by nature to match his lively brain), I am entrusted with the taking down of the words that fall from the lips of those in the Great House; and being of inquiring mind and still something of a stranger here, I have much cause to ponder upon the curious world in which I find myself.

For instance:

In my birthplace, while we have the same formal written language as all Kemet, we have a dialect that falls much easier on the ear: at least when we speak it has a flowing sound. There are places in it, as in my name when properly pronounced, where a gentler emphasis comes, as: Kah-ee-race. Not so in Upper Kemet and stately Thebes. Here the language is harsher and more abrupt. The name of the Good God may be written "Amonhotep" (life, health, prosperity!) but when they say it in their slurred, birdlike speech it becomes something like: "Mnhtp." Try that, if you will!

They write the Great Wife thus: "Tiye." But they pronounce her name, as nearly as I have come to understand them: "Ttt." And I, Kaires? "Krs," if you please!

If you would listen to a weird, amusing clamor, come with me to the docks here in Thebes where the unending boats come and go, or walk among the pillars and temples of Karnak when the worshipers gather for festival, or wander in the market any morning. Shrill, twittering, a constant rush of sibilants, gutturals and swallowed syllables overwhelmed by the quick gulps and hurried intakes of air that are only designed to keep the speakers alive until one statement can be completed and another slithered out like a snake—it is enough to make the foreigner shake his head in bafflement when he does not laugh outright.

Since no one laughs outright at the ways of the land of Kemet or at the immortal ancestors of the Good God in the Great House who ordained these ways many, many hundreds of years ago, I decided early to shake my head and offer a helpless smile. This technique will produce gales of friendly laughter and a patient attempt to assist the stranger. Eventually one learns: and I am now already becoming quite proficient. As a result, Amonhotep the Scribe thinks that I will go far. My father has taken no notice of me yet, so I do not know what he thinks. But I agree with Amonhotep the Scribe.

"Foreigner … stranger." I note that I use these words almost automatically even now, when I, who am fifteen, have been here already three months. With my blood, I am neither foreigner nor stranger—though I have promised my father, on pain of banishment (or possibly even death, for he is a very determined and righteous man), that this is something no one will ever know. It does give me, however, a greater interest than most in the land of Kemet. It is my observation that I respect its ways and traditions rather more than do some of its own—not including, of course, my father, who guards and cherishes the peace and order of Kemet above all things. In that I find that I am already becoming like him: more careful of Kemet, let us say, than some others who live in the Great House, whose interest in the order and stability of the Two Lands is not quite what it should be: as I see it.

Again, for instance:

Today, everywhere, in the streets, in the shops, in the common houses, on the farms, in the little towns and the great cities, all the way along the river from the Delta to the Fourth Cataract, there is light and jubilation in the land of Kemet.

Yet all is hush and tension in the Palace of Malkata.

Another child is about to be born to the Great Wife, Queen Tiye—a son, say the priests of Amon.

Here, if anywhere, it should be a happy day.

Yet it is a somber one.

Why?

I do not know, and it puzzles me; and although I spent the better part of half an hour at our sunrise meal, trying to discover from my friend Amonhotep the Scribe, Son of Hapu, what causes the Palace to lie shrouded with secrets, he turned me off with sly jests and laughter. But he did not fool me. The jests were halfhearted; the laughter did not ring with his usual confident air. Something is on his mind today, and I take this to be very significant, for he is very wise and knows many things. I am convinced he knows the inner troubles of the House of Thebes. But he will not tell me.

"You are too young for such weighty matters," he said airily. "And, after all: who says anything is wrong? You sound like the girls gossiping in the harem. Abandon such pursuits, little brother. There are better things for you to worry that busy head about."

Now in the first place, as he well knows, I detest this arch "little brother" business, which sounds patronizing in the extreme to one with my background and intelligence. It annoys me.

And in the second place, while I may be somebody's little brother, so casually do the royal gods and goddesses of Kemet breed with one another, I am quite certain I am not his. I told him as much in no uncertain terms. But again he only laughed.

"Be patient and keep your eyes open," he said finally.

"Very sage advice," I said sarcastically. "Worthy of a great scribe."

But he did not respond with his customary half-affectionate, half-acrid joshing. Instead his face fell suddenly somber, and he sighed. An elder's sigh can be rather devastating, particularly if the recipient is fifteen: Who knows what awful things it may portend?

We finished the meal in silence; the slaves cleared the simple utensils away. He was off to Karnak, two miles down the river, to witness the formal arrival of Amonhotep III (life, health, prosperity!), to seek Amon's blessing on the child about to be born. And I have been delegated for the day to assist Mu-tem-wi-ya the Queen Mother with the many letters she continues to send to her royal counterparts in the Middle East, even though her son has been on the throne for twelve years and she has long since ceased to have any influence.

"It keeps her happy," I heard him explaining just the other day to Queen Tiye; and since there is no harm possible from it—since her letters are all intercepted as they leave the Palace, are read by her son, and are then destroyed—it continues. Occasionally she expresses some mild surprise that she receives no answers; but the Good God merely asks her dryly, "What can you expect of the barbarians beyond our borders?" And since she has never thought very much of them this agrees with her own ideas and she accepts it with a shrug and a contemptuous, knowing little smile.

I think, myself, that the old lady—she is now forty-two, I believe, quite a great age for the royalty of Kemet—is remarkably well preserved, aside from the slight mental vagueness that permits her to believe this little charade. Or does she believe it? Sometimes the glance she gives her son is just a trifle too bland. He never appears to let it bother him, but it would make me uneasy, I think.

This morning I find her, too, to be in a mood that disturbs me. Normally with me she is very affectionate, very light, very fond, very motherly. She accepts our blood relationship tacitly, we never speak of it, but I know she knows: we gossip a bit. Already, in three months here, I would say I have become one of her most trusted confidants—indeed, a genuine friend. Normally, as I say, my hours with her are fun. Today she too is gloomy, restless, uneasy. Her words are sharp, impatient. There will be no letter writing this time. I discover she too is going to the temple of Amon: she tells me they are all going.

"You had better come with me, boy," she says, clapping her hands sharply for the ladies in waiting, who come scurrying up, twittering and chattering nervously, with the kohl for her eyes, the heavy gold rings for her fingers, the pectorals of lapis lazuli, carnelians and turquoise to hang around her weathered neck, the thick black wig to cover her shaven skull and surround her small, sharp face, the royal gold circlet with the uraeus, the poised jeweled cobra above her brow which she still wears on state occasions. "You might as well see us all in our finery asking the blessings of the priests on this new child. We put on quite a show."

And so they do, and today, as I too arrive at Karnak as the hour nears noon, seeing my friend Amonhotep the Scribe already well situated just by the entrance to the temple of Amon—he waves with a cordiality that asks forgiveness for his earlier sharpness, and I, naturally pleased at this public sign of favor from one so influential, wave back vigorously across the shoving, jostling, amiably colorful crowd—I realize that they will all be here, the House of Thebes and those who serve them most closely. They will be dressed in their finest—and I have learned already that it can be very fine indeed—for the edification of the people, for whom they are no more nor less than the embodiment of a dream, a fixed, unchanging and eternal dream in the unending story of Kemet, the great, the favored, the one and only land.

Today it appears they are all coming by water, straight down the river from Malkata, instead of crossing to the east bank, taking chariots, and arriving with a great jangle and snorting of horseflesh, which is what Pharaoh has lately taken to doing.

It seems better that they use the river this day. The Family and the river—they belong together on great occasions. It is more befitting. This I feel and so, evidently, does the crowd, for its response to them all is wild, excited, reverent—and loyal. Whatever troubles the House of Thebes, it has nothing to do with its relations with the people. The people are cheerful, happy, satisfied with their world, obviously worshipful and loving of Pharaoh, his family and his servitors. I must continue to look elsewhere for the answer to the undercurrent of unease that lies within the Palace, for certainly it is not carried over openly, here among the crowds.

Listen to them shout! I ask you: Was there ever such an awed—such a loving—such a satisfied sound?

Mu-tem-wi-ya is the first to arrive, myself crouching inconspicuously, almost concealed, at her feet. She stands in the prow of the barge, which is painted with electrum, the mixture of gold and silver so popular with the highborn in Kemet. Her right hand rests lightly but firmly on my shoulder, just enough to steady herself, not so obviously that anyone along the shores can see. A great shout of greeting, deeply affectionate and respectful, begins as her barge puts out from the landing at Malkata; it continues steadily all down the river to Karnak; it reaches crescendo as she relinquishes her hold on my shoulder with a quick, affectionate squeeze, and is handed to the dock by the Vizier Ramose, glittering from head to foot in his robes of gold, his great black wig gleaming down each shoulder, his staff of office held reverently at his side by a slave from far-off Naharin, north near Syria, come to his service through who knows what happenstance of friendly tribute or conquest of war.

Ramose keeps his face stern and grave toward the Queen Mother, although these two are good friends. I have noted that no one of royalty or rank—with the single exception of Pharaoh, whose smile is fixed—ever smiles in public in Thebes: it is all very stern, very proper, very forbidding. At first I found this somewhat offensive, accustomed as one is in other places to a more natural way of conduct, even among the great. But it has not taken me long to see the reason, to understand it and approve. These are gods and those who serve gods: and such do not smile. Gods are not human or they would not be gods. Many centuries ago they learned this: how much easier it is to govern through love if love includes a very healthy share of awe and fear. This too is befitting. Pharaoh's ritual smile is benediction, but it is so remote and inward-turning that it is also promise of great retribution if things do not move in ways pleasing to him.

So Mu-tem-wi-ya arrives, accepts Ramose's grave greeting with a nod of even greater gravity, then walks alone along the processional way, hot in the eternal bright sun of Kemet, that leads from the river to the cool dark entrance to Amon's temple. The avenue is empty of people. It is guarded along each side by soldiers rigidly at attention. At their backs the crowds fall suddenly silent as she passes. She pauses for just a moment at the entrance (I having already slipped through the massed thousands to squeeze in beside Amonhotep the Scribe, who gives me an affectionate smile of greeting); two white-clad priests of Amon step forward to assist her; she bows low, gives each a hand; and so flanked, back rigid and erect, eyes straight ahead, disappears inside.

A curious exhalation, low, sustained, tremulous, gentle, as though the whole respectful breath of a people were being simultaneously released, comes from the crowd. Then instantly they turn away, excited and happy again, back toward the river, as in the distance comes another rolling wave of roars and cheers. The next members of our royal gathering are about to reach us. Amonhotep and I strain eagerly to see who it is. The racing gossip of the crowd tells us before we can make them out: it is the two principal wives of Amonhotep III (life, health, prosperity!) after Queen Tiye—his oldest child, and so far only daughter, the eight-year-old Queen-Princess Sit-a-mon; and the Queen Gil-u-khi-pa, daughter of King Shu-ttarna of Mittani.

The Princess Sit-a-mon is a small, dark, laughing girl whom I have seen several times in the Palace. Today she too wears the customary frozen mask, though from time to time a little genuine excited smile breaks through, which the crowds love and greet with an extra cheer. So far I have not had a chance to speak to her, but in private she appears to be very sweet, very jolly, very trustful, and loving of the world. She is obviously adored by her father, though I am told by Amonhotep the Scribe that Pharaoh made her his bride solely and entirely to legitimize his own succession to the throne, and that he (Amonhotep the Scribe) is quite sure that he (Amonhotep III, life, health, prosperity!) has no other desires or intentions toward his own daughter. Quite often, I understand, these father-daughter relationships in the royal House are not that innocent: quite often children result. This case, my friend assures me, is different, although of course as the daughter grows older and more beautiful the father's self-discipline may grow less.

Basically, however, the marriage came about simply because in this land of Kemet succession to the throne passes through the eldest daughter. Therefore Pharaohs often marry their oldest sister to secure their hold on the throne. This Pharaoh had no living sisters at the time of his accession. His marriage to Queen Tiye, who was not royal (he was then about ten years old), was arranged by Mutemwiya, his mother, and by Mutemwiya's brother and sister-in-law, Yuya and Tuya, parents of Tiye and her two older brothers, Aye and Aanen. As Pharaoh and Tiye grew older their marriage developed into a genuine love match, so that now the Great Wife, Queen Tiye, sits almost equal with him on the throne, goes with him everywhere, is consulted on everything, in effect rules Kemet almost as much as he does. Love in itself, however, was not enough to provide the legitimate succession that Pharaoh needed. Therefore when Queen Tiye bore her first child, Sitamon—eldest daughter of a Pharaoh and, therefore, carrier of legitimacy—her father promptly married her to settle once and for all his claim to the throne.

Nothing like producing your own legitimacy, as my friend remarked dryly in one of those confidential remarks with which he has already come to trust me; but in this case it solved the problem, was accepted joyfully by the country, and now Queen-Princess Sitamon is fully as popular as her parents, whose joy and delight she obviously is. She will never be permitted to marry elsewhere, of course, and as if to compensate, they shower her with constant attention, gifts, her own small palace and court within the complex at Malkata; and the people, understanding, seem to give her extra love whenever she appears—a small, bright, cheerful symbol of the strange contortions the needs of the throne sometimes impose upon the rulers of our strange land.

At her side today stands Gil-u-khi-pa of Mittani, a bride of state married for political reasons by Pharaoh a couple of years ago in his tenth regnal year. He issued a commemorative scarab about it, recounting how she arrived with "a retinue of 317 women." Many of these have been quietly married off to deserving nobles around the country. Gil-u-khi-pa also has been given her own palace within Malkata, but apparently, aside from an occasional rumored visit, as perfunctory as any he makes to the countless anonymities in his official harem, Pharaoh never goes near her.

This would fully suit a stupid woman, but Amonhotep tells me that Gilukhipa is not stupid. Instead, she is quite intelligent, alert, informed.

Official neglect therefore has made her jealous, turned her inward, made her bitter, waspish, vindictive. There is no sharper tongue in all Kemet, my friend tells me, than Queen Gilukhipa's.

"Stay wide of Gilukhipa unless you can use her to advance your own ends," he said the other day—a rather odd comment, since if I have "ends," at this point, he seems to be more conscious of them and more knowing about them than I am—"and if you do use her, be very sure you never give her anything she can hold over you. Because she certainly will."

I don't know what prompted his warning, but of course as with all I learn, I shall not forget it.

Now she rides along in the second royal barge beside little Sitamon, the latter's popularity concealing Gilukhipa's lack of it: the shouts seem to rise equally for them both, which is probably why Pharaoh decided they should ride together. It is obvious to Amonhotep the Scribe and to me that she knows this exactly and is, therefore, probably even more embittered than usual. Her back seems extra rigid, her eyes exceptionally fierce, her demeanor more than necessarily stern and aloof. It is not until their barge is nearing shore that she shows the slightest sign of human feeling. At that point Sitamon looks up at her, tugs excitedly at her hand, points at the great snakelike crimson and gold flags snapping from their standards all around the temple, and says something with an eager, delighted grin. Not even Gilukhipa can resist Sitamon, and for a second she smiles back, reaching down with a perfectly natural gesture to adjust the child's gold circlet with uraeus, which has slipped a bit to one side. The crowd rewards them with an extra roar. As if in reproval, Ramose greets them with an extra solemnity. They both become suitably severe again, walk together hand in hand down the glaring empty avenue, are met in their turn by the priests of Amon, and disappear inside the vast stone structure.

From up the river comes another welcoming roar, and for a moment Amonhotep the Scribe and I speculate as to who it can be. The ranks of the House of Thebes are rather thin, at the moment: Pharaoh has his mother, no brothers, and sisters, Tiye so far has produced only two children, and all in all it is rather a shaky house. Tiye's delivery later today (it is generally understood that she began labor just before noon, and is progressing well: how these rumors sweep through a crowd no one knows, but they do, and with an air of great authenticity, too) is expected to add one more son. But it will be several years more before the Good God can feel really secure in the midst of an abundant family. So who can this be coming now?

For just a moment Amonhotep and I speculate, though we know it cannot be so: can this be the Crown Prince, Tuthmose, named for his late grandfather Mutemwiya's husband Tuthmose IV (life, health, prosperity!), and the other three brilliant Tuthmoses who preceded him?

The Crown Prince is six now, and only two weeks ago was installed by his father as High Priest of the god Ptah, five hundred miles downriver in the northern capital of Memphis in the Delta. My friend professes to see something significant in this—he regards it as a direct defiance of the priests of Amon here in Thebes—and yet why should Pharaoh have to "defy" his own priests? All the temples, all the priests, all the people, all the land, belong to him; he is the Good God who carries the word of all the other gods to us mortals. He is supreme. He is God. What need for him to "defy" anybody? Nonetheless, my friend becomes very mysterious and deliberately uninformative. I expect I shall have to probe for more, as time goes by.

Right now he says excitedly, "Wouldn't it be something if he has had the boy brought down to sacrifice for his new brother right in the temple of Amon! Wouldn't that be something!"

And for a second he almost hugs himself with excitement. Then he remembers abruptly where he is, pretends to be scratching his sides, relaxes and looks away.

"It couldn't be," he mutters out of the side of his mouth as we turn again to stare together up the river. "He wouldn't dare."

It comes as a profound shock when I finally realize, after a couple of disbelieving moments, that by "he" my friend means Pharaoh. It is the first, though I am beginning to suspect that it may not be the last, time that I have heard subversion spoken aloud in the hard bright sun of Kemet. Whom does Pharaoh have to "dare"? Again, I make a mental note to probe further.

For the moment, I myself do not dare to catch my friend's eyes or indicate in any way that I perceive his meaning. We add our voices to the roar that now mounts steadily as the next great electrum-gilded barge approaches the landing. My friend gives a little grunt as we perceive who it is: not Tuthmose at all, of course, but the Councilor Aye, brother of Queen Tiye, son of Yuya and Tuya, nephew of Mutemwiya, member of that powerful family from Akhmim whose destiny seems to have become increasingly entwined, in these recent years, with the destiny of the House of Thebes. And will so continue, I hope for several reasons—not least being the welfare of Kemet, to which I already know all of them to be deeply devoted.

Aye is unusually tall for a man of Kemet, nearly six feet, where most are rarely more than five; in this he resembles his aging father, Yuya. He is a man whose visage in ordinary circumstances is almost as stern as it is on ceremonial occasions such as today; a man austere and somber—a man of state. I have talked to him directly only once, but even on that occasion, which one might have expected to be reasonably relaxed and friendly, there was no diminution of his remote and solemn manner. My immediate impression was that he simply adopts at all times a forbidding and indeed "stagy" aspect, seeking thereby to evoke an awe and deference men might not give him otherwise. I very soon concluded that this was too facile an explanation. Aye is solemn and thoughtful, careful and remote, because that is really the way Aye is; and the evidence of this is borne out by the fact that, of all men at Pharaoh's Court, none wields more influence, both openly and in secret, than he.

Already he has succeeded Yuya as Master of the Horse; already he too refers to himself in his formal titularies as "one trusted by the Good God in the entire land … foremost of the companions of the King … praised by the Good God." This flowery rhetoric, which I perceive to be standard in our land when men of importance refer to themselves, in his case, recognizes no more than fact. He is indeed foremost of the companions of Pharaoh the King, he is indeed trusted, praised and given power in some ways equal, though often more indirect, to that of the Vizier Ramose himself. In relation to Ramose and all the rest, he has one paramount advantage: he is brother of Tiye and brother-in-law to Pharaoh. But in Kemet, where men are amazingly well judged on what they can actually do, and where the lowliest in origin can rise upward rapidly through the society if he has the ability, this would not be enough to take Aye so far if he did not deserve it. He is, I have concluded respectfully already, a very wise, very perceptive, very farseeing, and very patient man.

Today he gives no sign whatsoever of the fact that intrigues the whole land: That his wife also lies in labor in their modest villa inside the Palace walls. Should it be a son, the House of Thebes will someday have another good servant to thank, along with Aye and Yuya, for its successes. Should it be a daughter, a destiny much greater may await. Twice, in Mutemwiya and in Tiye, the family of Aye has produced queens for Kemet. May it not do so sometime soon again?

None of this shadows the thin face, high cheekbones and level, intelligent eyes of the Councilor as he stands like a statue in his barge, nearing the dock at Karnak in front of the avenue of priests. For him, too, the people call out, and the sound that accompanies his progress is great. But for him there is not the affection they gave to Mutemwiya, the fond reception they accorded Sitamon and, with a good-natured generosity, extended also to unhappy Gilukhipa. There is more of solemnity in the cries they give for Aye. He is not liked in the way others are liked, for no man so austere and so obviously enwrapped in his own thoughts—Aye's thinking, as my friend Amonhotep the Scribe put it to me, is louder than most men's conversation—can ever evoke quite the unrestrained popular response given to others. He thinks, and he makes people think when they see him: in the presence of such an obvious intelligence, a deep respect, tinged not a little with awe, is all that he can expect. It is what he gets, in a greeting that accompanies him to the landing and then ceases, as abruptly and as dutifully as it began when his barge took water fifteen minutes ago upriver at Malkata.

And then suddenly, far off but heavy and insistent like the noise of some great reverent sea, a sea whose waves sound for no one else so profoundly, solemnly yet joyously as they do for him, the unmistakable noise begins and grows until it seems to envelop the universe. From Malkata the final barge has set out, and no one anywhere in all the world could have slightest doubt of who it carries.

The One Who Lives in the Great House, Strong-Bull-Appearing-As-Justice, Lord of the Two Lands, Establishing-Justice-and-Causing-the-Two-Lands-to-Be-Pacified, Horus of Gold, Mighty-of-Arm-When-He-Smites-the-Asiatics, King of Upper and Lower Kemet, Lord of Truth Like Ra, Son of the Sun, Ruler of Thebes, Given Life, the Pharaoh—Amonhotep III (life, health, prosperity!) comes.

Now the world splits wide with sound, the earth trembles, the skies are rent, the Sun looks down upon his Son with happiness and all of Kemet rejoices, united in one heart, one mind, one dream of unchanging order that has already managed to survive for nearly two thousand years and will go on into the future, as we say, forever and ever.

I find my eyes are wet with tears, I am shouting like the rest, at my side my friend is similarly overcome. It is impossible not to be moved as Pharaoh approaches. Yet even as I tremble, some cold, small machine inside continues to observe: I too am perceptive, farseeing, and patient, and soon I too hope to be wise with what I learn in Thebes.

So as his barge—not plated with electrum like the others, but, as befits Pharaoh, all in gold—comes slowly, slowly down the Nile, the oarsmen aiding the current with deliberate cadenced strokes in response to the rhythmic cries of the helmsman, the six trumpeters along each side of the craft sounding triumphant blasts from their long golden instruments at regular intervals, the long thin streamers, scarlet, blue and gold, flying from the golden canopy over the golden throne, everything glitter, everything gold, I study Amonhotep III (life, health, prosperity!), ninth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty to rule the land of Kemet.

I am thrilled by the presence of the God: but I analyze the man. In this I think my father might be proud of me, though he could never admit it, of course, for to analyze the God aloud, or to let it be known to anyone that you are doing it, is treason and sufficient to bring death if discovered. Only Amonhotep the Scribe, noting my shrewd eyes searching through their emotional tears, realizes, I think; and already I think Amonhotep the Scribe is a true friend of mine, who will not tell. He thinks I have "ends" to seek in Kemet, and already I feel he is beginning to take an active and encouraging role in them, though I myself am not even sure yet what they might be.

The great barge begins its final approach down the channel to Karnak. And all the world cracks wide with sound … for what?

I see a small, brown, stocky, round-faced man in his twenty-second year, his height, perhaps five feet two inches, more characteristic of the country than Aye's tallness.

To cover his naked skull he too wears the formal wig, its two pendant flaps descending on each side to rest upon his chest, the whole draped with a striped cloth of gold bound around his head. On his chin he wears the narrow-cut, false beard of ceremony, a traditional regal anomaly in clean-shaven Kemet. Over all is the round, domed Blue Crown of the Two Kingdoms, made of leather, and studded with gold sequins. It is encircled by the uraeus—in his case, not one but three cobras, poised to strike his enemies—the cobra being the emblem of the goddess Buto, patroness of Lower Kemet, who in turn is associated with the vulture goddess Nekhebet, patroness of Upper Kemet, thereby symbolizing the union of the Two Kingdoms. (The gods and goddesses of Kemet are another subject. Intelligent though I am, I shall have to study that one for quite some time before I can even begin to understand its endless ramifications!) Behind the cobras is the disk of the Sun, which is known here under various names in its various forms—as "Re," "Ra," "Re-Herakhty," most importantly, "Amon"—and of late, with increasing emphasis, particularly in the royal House, "The Aten."

Pharaoh's body is clad in the pleated kilt of royalty, also of gold, held at the waist with a broad belt of gold encrusted with jade, amethyst, malachite, garnets, lapis lazuli, jasper, turquoise and pearls. Lodged in the belt is a wicked-looking jeweled ceremonial sword.

Loosely yet firmly he holds the traditional crook and flail, also gold, which, stretching back into the remotest antiquity of Kemet when kings first came out of the fields, symbolize his role as kindly yet all-commanding shepherd of his people.

On his face he wears a fixed smile, an expression stiff but more pleasant than the others. To the Good God it is permitted, as it is to his young daughter, to smile just a little, but for different reasons: she because she is a child … he because he is the supreme ruler of all men and all things, Son of the Sun, head of the Empire, servant yet co-equal of the gods, center and mover of the universe.

How must it feel to be born to such a place!

How must it feel to sit there?

I study his face closely as the golden barge approaches. Nothing speaks to me from its careful blandness but an opulent, youthful, self-satisfied, self-indulgent divinity. Yet there must be more behind: he, too, I am sure, must be affected by the unease that grips the Palace. But of course he cannot show it, and perhaps, buoyed up by the deafening happy scream that accompanies him, he does not feel it now, has forgotten it for the moment, thinks only of the excitement of the occasion, thinks only of another son being born—thinks only of being God.

Standing to the left and just behind the throne, solemn and stern, wearing the traditional high priest's leopard skin, is his other brother-in-law, Aanen, younger brother of Aye, older brother of Queen Tiye, Second Priest of Amon in the temple at Karnak—second only to Pharaoh himself as ruler of the priests of Amon whose temples and holdings, fanning out up and down the river the length and breadth of Kemet, in farms, granaries, thousands of cattle, hundreds of smaller temples, minerals, gold, all kinds of wealth, equal in some ways the power and influence of Pharaoh himself.

What does Aanen think, too, and what does it mean to stand in such a place? He is not the man his brother is, and yet he holds great power.

Gently the barge touches land. As if by magic all sound stops. The ears still ring with it in the great hush that descends as Aanen steps first ashore, exchanges grave greetings with Ramose, turns and bows almost to the ground. With a stately slowness Pharaoh rises from his throne, hands to Aanen his crook and flail, steps ashore, reclaims them, crosses them again upon his chest; bows gravely to Ramose, also almost prostrate before him; and then proceeds, not looking to right or left in the absolute silence, to follow Aanen with slow and measured tread into the dark, mysterious entrance of the temple.

Once again comes that curious, quivering tremulous exhalation, as of a whole people breathing its soul in one great all-embracing sigh, which followed in lesser degree his mother. And then behind the soldiers the crowds begin to move, swirl, change. Voices break out, children cry, dogs bark; all becomes happiness and chatter as the people prepare to settle themselves more comfortably to await the return procession. None wish to leave, for all pray with Pharaoh for the safe deliverance of a strong son pleasing to Amon; and besides, now the pomp is over for an hour or so. It is time for picnic, before they must silence themselves to greet again, in suitable love and reverence, the Good God.

Amonhotep the Scribe asks me to hold his place for him while he goes and relieves himself in the public place behind the temple. I promise lightly: if he will return the favor. Being closer to the Palace, we are both still a little more under the spell of Pharaoh's passing than the amiable crowds. We laugh but we are still moved, still thoughtful; our minds still race with many speculations, many things.

As I watch his compact little figure go scurrying off on nature's business—the crowds making way for him respectfully, for it is well known that Amonhotep the Scribe, Son of Hapu, is a favorite of the God and exercises much influence in the Palace—I think about the pageant I have seen.

In this first great public ceremony I have attended in Thebes, I have been moved, touched, stirred: the mystique of the God has reached me, I will not deny it. Yet still the cold little machine inside keeps wondering: What lies behind, what does it all mean, what does it add up to? If the Two Lands are really well ruled by this solid little figure in the golden clothes, what means the unease in the Palace of Malkata?

I have seen him pass, glittering, glittering, and I wonder what he thinks.

I know what I think, though I take much care to conceal all trace of it when Amonhotep returns refreshed to keep his part of the bargain and release me so that I, too, may hurry back to stand in place another hour to see the golden figure go.

I think that I care more already, in my heart and mind, for the land of Kemet than he does. I do not know how I sense this, but I do. And I wonder if I will ever have the chance to give to her the devotion and the prudent husbanding which she deserves.