After a childhood in academia, J. Daniel Sawyer declared his independence by dropping out of high school and setting off on a series of adventures in the bowels of the film industry, the venture capital culture of Silicon Valley, surfing safaris, bohemians, burners, historians, theologians, adventurers, climbers, drug dealers, gangbangers, and inventors before his past finally caught up to him.

Trapped in a world bookended by one wall falling in Berlin and other walls going up around suburbia and along national borders throughout the world, he rediscovered his deep love of history and, with it, and obsession with predicting the future as it grew aggressively out of the past.

To date, this obsession has yielded over thirty books and innumerable short stories, the occasional short film, nearly a dozen podcasts stretching over a decade and a half, and a career creating novels and audiobooks exploring the world through the lens of his own peculiar madness, in the depths of his own private forest in a rural exile, where he uses the quiet to write, walk on the beach, and manage a production company that brings innovative stories to the ears of audiences across the world.

Find contact info, podcasts, and more on his home page at http://www.jdsawyer.net

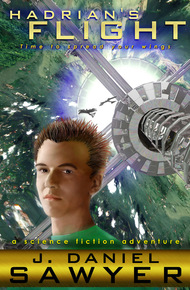

Hadrian Jin. Skyguard. Refugee.

Twelve times a day, this sixteen-year-old proprietor of Luna City's best orn-suit shop fits the wings, and jumps out into the open air to soar with the grace of an eagle. For forty dollars an hour, he can teach any groundhog how to fly bird-fashion in the moon's low gravity.

But when the tramp of military boots on the road to his home forces him to flee, he finds himself adrift between planets, on the run from government agents, without hope of home. Out of his depth and thrust into danger for which he's ill-prepared, Hadrian must learn the true reason for his exile, and finally spread his own wings...

...before war comes crashing down around him.

Humans can't fly like birds. We're too heavy—a fact which led my younger self to bitterly curse the injustices of physics. But in Lunar gravity, the math works, and I have no doubt that one day soon we will fly like birds in cities on the moon. Hadrian anticipates that day. A teenage flying instructor whose love of his sport drives him to bring it with him to other environments in the solar system where humans might also one day spread their wings and take flight. – J. Daniel Sawyer

"J. Daniel Sawyer has the most amazing voice of any writer I've ever encountered."

– Kristine Kathryn Rusch, author of The Retrieval Artist seriesFrom his vantage atop the long thermal column at the bottom edge of the ag dome, Haddy Jin scoped the hundreds-meter depth below him through his blink-lenses. Flicks of his fingers tweaked the primaries on his wings, allowing him to cut a grand circle in his designated airspace, sandwiched between a hard ceiling at the entrance to the ag dome and the top level commercial space of the Gallery.

Two fast blinks zoomed him in by a factor of ten. It made the image jittery, but it let him focus right down to the bottom of his zone where the Gallery shaft met the opening of Reservoir Cave.

No trouble down there, either. Nobody straying too close to the caged tracks where the massive lifts—with their on-board refreshment shops—ran from the bottom to the top of the Gallery at all four corners.

The fledgers—easy to spot with their wings marked by green stripes and blinking lights at their wing-tips—weren't allowed into the cave, where they had room to really get in trouble. They had to get the basics down first—the circling rise, the circling descent, the deliberate stall, the hard dive, the flattening recovery. The space in the Gallery wasn't exactly ideal for it—after training more fledgers than he could count, Haddy was of the firm opinion that the Gallery could stand being about four times its current size, in order to give the fledgers some horizontal latitude.

But not letting them go too horizontal was the point, according to the skymaster. First they had to get used to having wings, to trusting that the wings would carry them, then they had to get used to dealing with the z-axis as if it was a normal thing. Height was safe—the higher you flew, the more time you had to recover from a problem. But, given the option, most fledgers would stick right near the ground, where they had no margin for error.

Because, they thought that falling was something to be afraid of. Which, apparently, was "normal."

Haddy didn't believe it for a minute. "Normal" couldn't be that stupid, or humans wouldn't have ever made it out of that awful gravity well where they'd started off.

Besides, Haddy knew it wasn't normal to be scared of heights—after all, he'd taken his share of tumbles, and broken a few bones, but not once since he could remember did he look over a ledge and get any kind of flutters other than the excited kind.

Heights were for soaring on. And on Luna, terminal velocity was only thirty-three kph for a flat fall anyway. A hard fall wouldn't do more than bang you up a little bit, unless you were mush-brained enough to fall on your wing (and get stabbed by a broken strut) or on your head (and maybe break your neck even if you were wearing your helmet).

Anyone who was that stupid kind of deserved to spend a month or two in the hospital getting themselves rebuilt.

But, he had to admit, most people he'd trained over the years had been more than a little defective in the brain-meat. They did get woozy at heights, and they kept trying to do acrobatics before they knew how the gear worked.

And then there were the wannabe dog fighters. They never waited until they were ready to go crazy.

Not that there was anything in the world better than dogfighting. Snap your gaming goggles on, dive down to Reservoir Cave, and go at it team-on-team until everyone on the opposing team was dead—then go again. High-bank turns, hard flaps and peregrine dives and Herbsts and Cobras, enough to leave even Haddy's head spinning and his chest heaving for oxy.

Haddy side-slipped out of the thermal and descended for a bit. He didn't want to stray too high. If he broke the beam grate at the ceiling, well, that would mean a fine that would eat up half his bonus for skyguarding, and it would bump him down on the performance charts, too, and that would keep him out of a Reservoir Cave post.

That's where the primo assignments were. Two solid klicks long, half a klick wide, plenty of room to fly, with ducts at both ends to keep the air moving. Two major waterfalls coming off the condensation towers to swing round. It was the best place on the colony to fly, except for the race course, but that wasn't open to fliers except during competition and practice. Down in the cave you weren't keeping an eye on fledgers, you were making sure the dog fighters and advanced fliers behaved themselves—especially that they didn't break the hard-deck.

That was always a problem. More common than near-misses. When you were soaring up three hundred meters in the top of the cave by the condensation towers, and you saw all the naked people swimming around and laying out on the rock beaches and generally running around like ants, it was pretty hard to resist the urge to swoop down and spook them. You did that over the water and they all dove down to get clear. Do it over the land and they scattered like gazelles running from a lion. It wasn't very nice, but it never stopped being fun.

But if the skyguard caught you, you'd get a big fine. Haddy'd gotten caught doing that enough times that it hurt his bank account just thinking about it. And if you got caught doing it too often, you'd get grounded, sometimes for months.

That had been the worst six months of Haddy's life—manning the booth renting out the wings, never allowed to put them on himself, looking at all that glorious air just aching to get flown in, and not able to do anything about it.

He'd been flying since his arms had been strong enough to handle the weight-load of the orn-suits his family had designed and manufactured for the last forty years, ever since they'd immigrated. Not being allowed to fly was like not being allowed to walk. He'd have liked it better if they'd just shoved him in a closet for a few weeks—at least then, he wouldn't have spent all his time looking at the one thing he couldn't do.

That had been the last time Haddy had ever even thought about swooping at the bathers.

And now, since he'd just turned sixteen, he'd graduated from training tourists in how to fly to being a mobile air-traffic controller. Now he got to enforce the rules, instead of getting them enforced at him. Those hundred-or-so fliers working in the training space below him were depending on him to keep them safe.

Once upon a time, there had been roads back on Earth where people operated their own high-speed rovers that weighed enough to mow a grown man down and not even notice it. Haddy had actually seen some in person in a museum display in a place called Reno, where his uncle Jorah had taken him for a suffocating high gravity vacation a couple years ago. They looked like retro-future sculptures to him—the kind of thing you might see hanging from the ceiling at the Juno—it had taken some convincing and a full documentary for him to believe they'd actually been designed to move people around.

The documentary showed people moving around in them, though, with an amazing degree of order and a minimum of carnage. It was as if everyone had somehow agreed to drive one direction on one side of the road, and another direction on the other side, then gone on to make customs for sorting out whose turn it was to move at an intersection, and conventions for dealing with people who were foolish enough to go walking next to those hulking metal machines.

He'd been quite gob smacked, at least until Jorah pointed out that the sky had the same kind of rules:

You couldn't pass within two meters of another flier unless you were flying in formation.

You had to stay four meters minimum from a wall, unless you were heading in for a perch or a landing.

You circled counterclockwise to climb, clockwise to descend.

In the Gallery, up and down right-of-ways were controlled less by rules than by air flow—the heat from the ag dome above, and from the climate-control radiators at the bottom of the shaft created a natural thermal that hugged the south face.

A little red dot blinked in Haddy's blink-lens display. Five minutes left in his shift, and everyone had been depressingly well-behaved. He hadn't gotten to write a citation all week.

What happens when you're enforcing rules that nobody's breaking?

You get paid to mill around in big circles trying to look at girl's butts with the zoom on your blink-lenses—which never worked, because from the top, under the wing rigs, you could barely see anyone's butt, let alone figure out the sex of the person who was wearing it.

Oh well. He needed to get in, scrub down, and put on his other suit so that he could pick up some training clients. His account was already almost all recovered from the coin he dropped buying Josie last semester—the faster he could bring it back up to parity, the sooner he'd be able to lay off the extra work and spend more time up on the surface, working on his novel. He'd built himself a cave out of loose stones a little ways north of the crater, where he'd stashed himself a private dictation setup.

Haddy descended lazily, barely paying attention to what was going on around him, moving slowly, finding a groove in the tourist-clogged descent lane as if he were negotiating rush hour at the tram station.

Then, without knowing why, he dipped his left wing. An automatic reflex.

A soft gecko boot blasted just over the dipped wingtip, missing him by only a few centimeters. He barely had time to feel a blast of lemon-scented air on his face before his wings surged, pushed him up, and stalled hard.

Haddy swore as he found himself in a sideways tumble. Falling slowly, then more quickly, as one level, then two, then four tumbled by him in an endless handful of seconds. He reflexively pulled his wings in, which increased his spin speed. He pulled his toes in toward his body and bent double into a jack-knife, canting his faux tail feathers down flat against his hamstrings, then straightened out again pointed straight down.

He speared down like a peregrine falcon, spinning corkscrew-fashion with the angular tumble he'd picked up from the stumblebum tourist's wake. Then, once he was in a more-or-less stable dive, he pulled his toes in again, but this time he didn't bend at the waist. Instead, he pushed his wings out, crooked at the elbows, and curled his fists in.

The wing-tips and tail-feathers bit the air, steadying his spin and pulling him into a swoop.

An instant later he was climbing again, pushing straight up with his momentum, scanning every-which-way for the creep that had bum-rushed him.

There. Almost at the top, flapping hard, zipping in and out of the lanes, trying to push up through the ceiling into the ag dome. He blinked twice, zoomed in, got a bead on the wings and the flyer. They were solid blue wings, with no fledger stripes. Whoever was doing that had been out at least once before, and should have known better.

They were strapped to a girl, maybe sixteen or seventeen years old, who didn't seem to give a good goddamn who she knocked out of the sky.

Well, she would soon. Nobody pulled that kind of stunt and got away with it. Not in his sky. Haddy burned with the righteous rage of his office. Oh, he was gonna get to throw the book at her. In five minutes, he'd make good and sure she was a lot poorer, and maybe grounded for a few weeks.

But he had to get her before she busted the ceiling, or he'd get it right in the neck for letting her get up where she could interfere with the city's food supply. If she crashed in the triticale, or god-forbid the corn, she'd cause enough damage that the farmers would start agitating to get the fliers banned from the Gallery. It had happened before, and they'd always lost, but that didn't mean they'd lose next time—and if they did win, his whole family would be screwed.

The thermal was clear for most of the way up. Haddy flapped hard, goosing his speed, banking into the thermal, using the rising column of air to help push him faster.

He dodged out into dead air as he caught up to the soaring fledgers, then back into the thermal before he stalled out.

"Hey!" he shouted. "You in the blue! Stop!"

She kept right on soaring up like she hadn't even heard him. She was crossing into the skyguard's nest now. Another twenty meters, and she'd bust that ceiling like it wasn't even there.

Haddy pulled against the air like a champion rower, pushing vertical faster than he'd been falling before his dive.

He was gaining on her.

He hauled and pushed. He had to resist the urge to kick his legs—if he did, his tail feathers would cant back and forth and drag him down, queer his vector, and lose him the chase.

"You in the blue!" He shouted between panting, loud enough to make himself hoarse. "Up top! Can you hear me?"

She looked down. He was close enough to see her head bend toward him. She made eye contact.

She could hear him.

"You're nicked!"

"What?" She wasn't pushing against the air anymore, but she was still riding the thermal up.

It wasn't a surrender, but it was enough. Haddy took the opportunity presented, exhausted himself completely fast-climbing the rest of the way up, closing the distance before she busted the ceiling.

"Stop now! Don't climb any further!" he shouted. "You bust that ceiling and you're grounded for life."

"And who exactly do you think you are?"

Of course she couldn't see the badge-patches on his wings from this angle. He was only five meters below her now, so he canted his wings horizontal, letting them catch the full force of the thermal. Soaring instead of flapping.

Now she saw the badge-patches on his wings. He knew she did. Though he had to crane his neck to see it, she got that look. The one he'd given skyguards a dozen times before, the one where you roll your eyes and your face goes slack because you know you're completely, totally screwed.

"S'crats," she swore.

"You're nicked," he said. He wasn't sure she heard him—he was breathing so hard he could barely get his teeth around anything resembling a word. "Follow me down. No showboating."

She shook her head—not like she was saying "no," but more like she was kicking herself for being stupid enough to get caught.

Then she slid sideways out of the thermal and glided to the other side of the gallery, and started a deliberately-slow I'm-not-going-to-do-anything-more-you-can-cite-me-for descent.

Haddy formed up above and behind her, and descended with her.

"Head for the roost on the west wall, level eight." The level numbers were painted in giant, unmistakable numbers on each wall, so that the fliers wouldn't get lost on the way home.

The prisoner—okay, she wasn't really a prisoner, but thinking of her that way made him feel very official, and he liked that—behaved herself perfectly. Now that he'd caught her, he didn't have a good gust of anger blowing him forward for the stunt she'd pulled, and he was secretly hoping she'd do a few more things on the way down that he could cite her for.

But she didn't.

And that really pissed him off.

Actually, come to think of it, she couldn't have done anything more calculated to annoy Haddy.

Oh, she was gonna get it, for sure.

Right in the middle of the gallery's seventeen main levels—which were sandwiched between the overlevels and the sublevels—a little neon orange platform stuck out about three meters from the marble-faced concrete half-wall. The tongue-launch for the first ever orn-suit flying operation in the whole history of the solar system: Bob and Ginny's Flying Lessons.

Haddy's grandpa had started it. He said he'd gotten the idea from a story he'd read when he was seven or eight years old, and he named the shop after the guy that wrote the story.

The oldest, and still the best. They'd even named the deck: Ginny's Perch. Haddy got a little sparkle of pride every time he set down on it. Now for the first time, he was using it in an official capacity, that sparkle was more like a private fireworks display.

The girl swooped in for a fast landing, then pulled up vertical at the last possible moment, scooping the air with her wings, then flapping hard twice at exactly the right time, putting herself in a vertical stall, and dropped ten centimeters to the deck.

Textbook perfect. And not an easy landing to do. It had taken Haddy until he was eight years old to pull that landing off, which was almost half his flying life.

Okay, a third, but who was counting?

Not to be outdone, Haddy swooped in low, then pulled back so he rocketed upward, and wrapped his wings around himself. He stalled out a full level-and-a-half above the deck—not bad since the levels were ten meters high once you factored in the thickness of the floors and ceilings, where all the wiring and ventilation ran—and let himself fall straight back down almost all the way to the deck.

When he reckoned he had less than two meters to go, he spread his wings out and flapped once with all his strength, and his feet lightly touched the deck.

He immediately found himself enveloped in a cloud of lemon perfume. It hadn't smelled half bad when he'd gotten a whiff of it blasting past him on the wing—up close, though, it smelled like whoever-she-was bathed in the stuff.

Haddy tried to not-breathe as much as possible while he took the PPD from his belt and deployed the stylus.

"All right," he said as he turned to her, "you're no fledger, so just what do you think you were..."

He ground to a halt as she turned to face him, and, for a moment, forgot what language he was supposed to be speaking—which was the least of his problems, considering that he also forgot what grammar was, the name he'd answered to since he was born, and how to supply his brain with oxygen.

She had blue eyes. Real blue eyes. Not pale blue, but the kind that looked like someone had run lightning through the oceans on Earth, to give them an extra sizzle, and then popped the result into someone's head. He'd seen great eyes before, sure. Everyone had. He even knew a place where you could buy them. But you couldn't buy eyes like these, not before you were eighteen, and if you did you'd never put them in a face like that.

It was the kind of face he'd seen in the bas reliefs in the Capital Dome down in Petra at the heart of Luna City. Round eyes, high cheeks, light bones as if she'd been built by a Gothic architect.

And that skin. Toasty brown. Indian, almost. But not quite. And no pimples either, and no freckles, and no makeup, and girls her age always had one of the three.

He figured her for about seventeen. Maybe nineteen. No older than that. And blonde. And stuck up, too, judging by the way she looked at him as if she wanted to laugh at the way he couldn't remember how speech worked.

And oh, boy, he'd better start talking before he looked like a complete derp.

"Is there a problem, officer?" She said "officer," but the way she said it made it sound an awful lot like "jerk off".

Okay, too late to avoid looking like a derp. But he could still throw the book at her.

"Hold still please." He tapped the "Citation" button on the PPD screen, and got an instruction in his blink-lenses that said "Facial Identification Required."

Right. He had to look her in the face again. This was official business, though. He could do this.

Haddy looked up, and focused his blink-lenses on her face. This time it didn't feel like she was looking at him—more like he was looking through a camera at her. Which was, in fact, what he was doing.

"What's the idea buzzing people like that? That's a proximity violation, and then there was a traffic pattern violation, and you almost busted the ceiling."

"Oh, tosh, I didn't even get close to hitting you. A girl tries to have a little fun..."

He tapped the PPD screen again, so the system would record her face. "Fun's fine. Endangering other peoples lives, especially fledgers, is not." Haddy recited, almost verbatim. "How long have you been flying?"

She shrugged. "I don't know. A few years, I guess."

"Then, I'm sorry," the PPD pinged. It had identified her, so he could assign the citation. He looked down as he continued his sentence, "but I'm going to have to recommend you be suspended. With that much experience there's no excuse for...what the hell?"

The ID field on the screen leapt out at him.

Charis Jin.

He looked up at her again.

"You're..."

She smiled like she'd just won some kind of prize.

"Hi cuz," she said. "Long time no see."