Jeffrey J. Mariotte has written more than seventy novels, including original supernatural thrillers River Runs Red, Missing White Girl, and Cold Black Hearts, and the Stoker Award-nominated teen horror quartet Dark Vengeance. Other works include the acclaimed thrillers Empty Rooms and The Devil's Bait, and—with his wife and writing partner Marsheila (Marcy) Rockwell, the science fiction thriller 7 SYKOS and Mafia III: Plain of Jars, the authorized prequel to the hit video game, as well as numerous shorter works. He has also written novels set in the worlds of Star Trek, CSI, NCIS, Narcos, Deadlands, 30 Days of Night, Spider-Man, Conan, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, and more. Two of his novels have won Scribe Awards for Best Original Novel, presented by the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers.

He is also the author of many comic books and graphic novels, including the original Western series Desperadoes, some of which have been nominated for Stoker and International Horror Guild Awards. Other comics work includes the horror series Fade to Black, action-adventure series Garrison, and the original graphic novel Zombie Cop.

He is a member of the International Thriller Writers, Sisters in Crime, and the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers. He has worked in virtually every aspect of the publishing businesses, as a bookseller, VP of Marketing for Image Comics/WildStorm, Senior Editor for DC Comics/WildStorm, and the first Editor-in-Chief for IDW Publishing. When he's not writing, reading, or editing something, he's probably out enjoying the desert landscape around the Arizona home he shares with his wife and family and dog and cat. Find him online at www.jeffmariotte.com, www.facebook.com/JeffreyJMariotte, and @JeffMariotte.

Richie Krebbs is an ex-cop, a walking encyclopedia of crime and criminals who chafes at bureaucracy. Frank Robey quit the FBI and joined the Detroit PD, obsessed with the case of a missing child and unwilling to leave the city before she was found. When Richie unearths a possible clue in one of Detroit's many abandoned homes, it puts him on a collision course with Frank—and with depths of depravity that neither man could have imagined.

How do people who dwell in the darkest places—by profession or predilection—maintain their connection to the world of light and humanity? Richie and Frank will need every coping mechanism at their disposal to survive their descent into darkness and emerge unbroken on the other side.

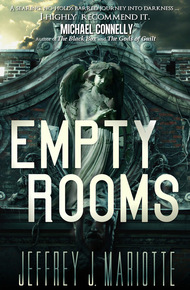

With Empty Rooms, bestselling award-winning novelist Jeffrey J. Mariotte introduces crime savant Krebbs and obsessive comic book fan Robey, who will quickly join the ranks of the most beloved heroes of thriller literature.

Jeff has been a long-time friend, well known as a comics writer and a media tie-in writer, but he has also penned his own original novels. When he came to WordFire with his exceptionally powerful EMPTY ROOMS—and a quote in hand from Michael Connelly—I was pleased to publish it, but I am eager to get more attention for such an exceptional novel. – Kevin J. Anderson

1

The Morton house squatted on the edge of its corner lot, as if it had tiptoed over while nobody was watching and waited there, trying to decide which way to spring. When Richie Krebs first saw it he said to his wife, "That place looks haunted."

Wendy didn't even glance his way, just stared out the side window of the borrowed red pickup, its bed piled high with their belongings. Checking out their new neighborhood. "Babe, this is Detroit," she said. "Every third house looks haunted."

Wendy was overstating the situation, and yet she wasn't. Their city's condition varied neighborhood by neighborhood, street by street, sometimes block by block. Native Detroiters, Wendy and Richie weren't immune to the impact of ruin porn, those inescapable photo essays focusing on the city's vacant homes, abandoned factories, and boarded-up storefronts. They had friends who bucked the trend, whose property values clung tenaciously to life. But they had given up on their own place, surrendered to foreclosure, and walked out on their mortgage. Their former neighborhood looked like it had barely survived nuclear war. By contrast, the one they were moving into was a vast improvement, as if it had suffered only a moderately bad pandemic.

The whole situation was depressing. One more layer of bad news, adding to the sedimentary crust of it that had been building for the past thirteen months. Their marriage seemed the only thing decent left in Richie's life, and it, too, creaked under the strain. He hoped moving to a new home, paid for with cash saved up by not paying their mortgage for several months, would improve things. Hope, however, was a scarce commodity these days, something he could only bring himself to parcel out in limited rations.

His worst times were the evenings, when he rose, unrested from daytime sleep, and got ready for work, donning the uniform he despised so much he hated to look in the mirror when he wore it. The provided shirts were a quarter-inch too short in the sleeves, frayed at the cuffs, and too tight across his broad shoulders. The tan shirts and brown pants, with their ridiculous, stiff gold stripes down the outer seams, were vaguely reminiscent of Nazi apparel. And all of it, especially the badge, reminded him of his own greatest failure: the shield he no longer wore.

He didn't believe he was suicidal; just the same, he was glad he no longer owned a gun. He remembered an instructor at the Detroit police academy he had attended, a burly man wearing a white shirt that strained at the shoulders and barely closed around his bull neck. The man had a silver buzz-cut and a fighter's nose, cocked to the right like a cabinet door with a busted upper hinge. "Never surrender your weapon," he had said. "If you give up your weapon, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, it'll be used against you. The last thing you want is to be shot with a bullet you loaded."

Turned out, that wasn't last on Richie's list, after all.

What didn't occur to Richie, in those optimistic rookie days, was that when the DPD fired you, they not only took away your badge but they reclaimed your department-issued firearm. Richie also got rid of the backup piece that his training officer had insisted he carry. Guns weren't hard for cops to unload. Some kept small arsenals at home or stashed in the trunks of their personal vehicles, and were always up for a bargain. Richie sold his backup to a rookie with a glow like an expectant mother's. He reminded Richie so much of himself, at that fledgling point in his career, that the conversation was literally painful.

The next time he paid any attention to the Morton house—though he didn't yet know it by that name—two minutes after he pulled out of his driveway on a cool April night, he briefly wished that he had kept at least one of those weapons.

His encounter on that night led to a different sort of education, one they couldn't provide at the academy. Safety is a comforting lie, he learned. What a person takes from life can't be given back, and what's given away is not easily reclaimed. He wished he could forget those lessons, wished they could be discarded as easily as steel and springs and gun oil. But forgetting is an illusion; once something is tucked into a pocket of memory, he found, it's there forever, and the more horrible it is the closer to the front it remains, easy to slip out and worry at, like a scrap of familiar fabric rubbed soft and ragged over time.

On the night Richie's lessons began, under a bright three-quarter moon, his headlights scraped past abandoned houses, empty windows gazing blankly across neglected lawns toward the cracked and crumbling street.

As Richie made a left at the corner, he braked for an old dog hobbling across the road, and slowed with those headlights aimed at the big corner house. A scraggly elm stood in the front yard. Richie was already looking away when he noticed a black kid with a crowbar heading toward the house. A black kid in Detroit was no more surprising than a foreclosure sign; one bearing a crowbar, still not entirely foreign. But it was eleven-thirty at night. The kid hadn't come to make any owner-approved modifications.

Richie had passed that vacant house at least twice a day for three weeks. It was easy to distinguish a newly vacant one from a long-time empty. Recent ones still had landscaping, the boards nailed over their windows were new, often bearing orange stickers from a lumberyard. Graffiti hadn't yet turned them into primitive message boards.

This house's yard was thick with knee-high weeds. Its windows were covered in wood that had taken on the gray patina of the siding, age and weather scraping and dulling its paint and providing a neutral background for the urban art decorating it.

As Richie watched, the kid cut along the side of the house, toward the back. Richie was no longer a cop—for a lifelong dream, that had been a brief and ill-fated adventure, six years and done—but he still wore a uniform with a badge on it. He braked his aging Ford Tempo and got out, clutching a Mag-lite in lieu of a gun.

Weeds brushed his uniform pants. There was a fence around the backyard but the gate dangled from a single hinge, wide open. Richie played his flashlight beam over the gate and beyond, lighting more of the same miniature jungle. He paused just inside the gate. "Hello?"

No answer, but he heard a quick, ragged intake of breath from around the corner. The kid had probably been headed for a back door. Richie wondered if he had a gun. So many did, these days.

"Security!" Richie said. "Come on out. Let me see your hands."

Another sharp breath. Hugging the wall, Richie rounded the corner.

The crowbar flashed in the Maglite's beam, spinning end over end toward him. Instinct shoved Richie back behind the corner as the bar slammed into the wall, spraying wood chips. By the time the crowbar thumped down in the weeds, the kid was sprinting toward the back fence.

The fence was a plank construction, six feet high. Boards gapped here and there, but Richie didn't want to count on there being an opening in the right spot. The kid was younger than him, and taller, lanky. Richie took off around the fence, toward the alley bisecting the block. He had always been broad-shouldered, lean and strong; in high school, coaches had shaken their heads in sad disbelief when they learned how little interest he had in athletics. He had worked out with weights even then, but only because he thought it would make him a better cop. His interests had always been narrowly focused. Lately, he had been slacking off on his running, down from ten miles a week to five or less, some of that at a walk. He'd let his gym membership lapse, too; he said it was for financial reasons, which was partly true, but even the weight bench in his basement was mostly used to dry laundry these days.

Before he reached the alley, he heard a crash. The kid apparently wasn't as athletic as Richie had feared. He had snagged a foot on the fence and come down hard, and when Richie reached him he was still trying to get unsteady legs under him. Richie didn't slow down, but plowed into him at full tilt. The kid went down again, entangling Richie.

They both wound up on the alley's dirt floor, Richie pawing for his flashlight. He scrambled upright and cocked his arm back, ready to use the heavy light as a club, but the kid just sat there, staring at him in the moon's glow, his heart beating so hard Richie could feel it through the cotton T-shirt bunched in his fist.

"You ain't a cop. Since when do security give a fuck who goes in these vacants?"

"Security doesn't," Richie said. "I do."

"What for?"

"This is my neighborhood."

"Guess you don't like crowds."

"What I don't like is people breaking into houses that aren't theirs." Richie shined his light onto the kid. He was maybe sixteen. Dark fuzz shaded his cheeks and his hair was cropped close to the scalp. He wore a coat big enough to fit three people his size, baggy jeans, and sneakers that could have served as clown shoes. But he didn't have any visible tats or scars, and his eyes were wide, his face open, almost friendly. Gangstas worked hard to perfect a sort of bored sneer, lips curling down, eyes hooded, or they offered a smirking, phony sincerity. This kid didn't show either of those.

Besides, Richie smelled rank sweat powering through the kid's overdose of body spray. He was scared.

That was good. He wasn't strapped. If he had been he would have shot Richie instead of chucking a crowbar at him. Richie was surprised to find himself somewhat relieved he hadn't.

"What you gonna do?" the kid asked.

"I should cuff you and hold you for the cops."

"Should?"

Richie didn't have the authority to arrest the kid. He could hold him, as he'd threatened, but that would make him late for work. In his three weeks on the job, he had already received two reprimands for tardiness. "If you promise not to break into any more houses I'll let it slide. You don't look like such a bad guy to me."

The kid tilted his chin up. "I bad as shit."

"Yeah, I didn't mean to insult you. Believe it or not, in some cultures that's a compliment."

"This here Detroit."

"Must have slipped my mind." Richie took a little spiral-topped notebook and a pen from his shirt pocket. "What's your name?"

"Why?"

"You want me to get out the cuffs?"

"Wil."

"Will."

"One L."

"What?"

"W-i-l. One L."

"Got it," Richie said. He crossed out the second L he had written. "Last name? Never mind, show me your driver's license."

"You don't trust me?"

"You threw a crowbar at me."

"Can I get that back?"

"You gonna use it to break into houses?"

Wil smiled. "Naw." He fished a wallet from somewhere under his coat and slid his license out. He was seventeen, and his full name was Wilmont Aaron Fowler. Richie copied it down, along with an address on Berkshire, on the east side.

"This your current address?"

"Yeah."

Richie's neighborhood was just south of Detroit's Boston-Edison district, as central as could be. "You came a long way to bust into a vacant. They don't have any closer to home? Give me your digits."

Wil spouted numbers. Richie wrote them down. He tore a sheet from the pad and scribbled on it. "This is me," he said. "Richie Krebbs. Call my cell phone if you need me, not Rampart Security. The receptionist there is a junkyard dog, she'd chew you up and spit out the gristle."

"Why you think I might need you?"

"You never know. Just hang on to it. And stay out of trouble, Wil, or I will make sure you go to jail. You feel me?"

Wil smiled. A gold tooth glinted in the flashlight's beam. "I feel you."

Richie got to his feet and helped Wil up. "I hurt you?"

"It's cool."

"Good. Keep away from vacant houses."

Wil nodded, and Richie left him there. He had wasted too much time, was going to be late anyway.

Nothing he could do about it now.

O O O

"Check it," Kevin Roche said. Kevin Roche was a husky black guy wearing a ball cap so tight it must have cut off the flow of blood to his brain. Lettered in gold on the cap's crown was "Security," and there was a three-bar chevron above that, testifying to his rank as a sergeant at Rampart Security. That meant an extra two hundred bucks in his bi-weekly take-home. And he got to drive the truck, until Rampart considered Richie fully trained and able to patrol solo.

Kevin had inclined his head toward a white van parked in front of a two-story home. Lights glowed from two upstairs windows onto an immaculately manicured lawn. Through a bay window on the ground floor came the rectangular, bluish haze of a wide-screen TV.

"That van?" Richie asked.

"Wasn't there last night or the night before, right?"

"I don't remember it, but I might have been blinded by all the Benzes and Lexuses."

"Need to make note of this kind of thing," Kevin said. "Anything that changes."

They were patrolling Palmer Woods, an upper middle class neighborhood, emphasis on the upper, in a white pickup truck with a gold stripe along its side and a light bubble on the roof. In the event of trouble, they had their Maglites, a radio, and a digital camera with a zoom lens. Most upscale Detroiters wanted to live beyond Eight Mile Road, so Palmer Woods, just the far side of Seven Mile, off Woodward, was in riskier territory. The people who held out there got to feel like they were bucking the odds, pioneers in the foreign landscape that Detroit had become, and they paid dearly for the protection offered by a private security company.

Kevin was training Richie in the ways of patrol, which Richie found more than a little ironic given that he had been a street cop for six years, whereas Kevin's previous law enforcement experience consisted of nineteen months on the security staff of the Sears at Summit Place Mall. But Kevin had been at Rampart for three years, during which time the company, and Detroit's private security industry as a whole, had enjoyed enormous growth while the rest of the city imploded. He seemed smart and capable, and Richie had tried a few times to talk him into applying to the DPD. But Kevin had no interest in being a real cop, so Richie didn't push it.

The job sucked. Leaving his house to drive to work made Richie's neck ache, sent tendrils of pain into his head. His gut churned, and every minute he spent on duty he had to fight back the impulse to flee, to get into his second-hand Tempo and drive as fast as he could, to head for Maine or Mexico or someplace else where he knew no one, where he wouldn't feel like a failure every time he caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror.

"Let's have a look," Kevin said. He pulled the pickup to the curb behind the van and left the headlights on. They got out of the truck. Kevin went wide to look in the driver's window, while Richie took small windows in the rear doors.

Inside, he saw racks and shelves and a couple scrawny bouquets of flowers. Petals carpeted the floor. "It's a florist's van," he said. "Or somebody has a really green thumb."

"Florist," Kevin agreed. He tapped the van's side. "'Bloomin' Love,' it says."

"Cute."

"Could be a fake. Or stolen."

Richie went around to the passenger side. Just then, a light came on over the house's front door. The door opened and a man stepped out. "Excuse me," he said. He was silhouetted against light from inside, the lamp above him revealing a heavyset guy with a fringe of gray hair. "Help you?"

"Rampart Security, sir," Kevin said. "This your van?"

"Yeah, I own the business. My car's in the shop so I drove a company van home. Doesn't fit in the garage."

"That's fine sir, we're just checking."

"Thanks." The man closed his door, and the overhead light clicked off.

"Answers that," Kevin said. "Let's roll."

Back in the truck, they cruised the community's quiet, winding streets. Kevin played WJLB softly, turning it off any time he called in to headquarters. Another perk of seniority, controlling the radio.

"Do you ever think there's something, I don't know, a little screwy about what we're doing?" Richie asked.

"Screwy how?"

"We haven't really done much tonight. Checked out that guy's van. Took pictures of a car we saw twice, on two different streets."

"Might be casing houses."

"I get that. But shouldn't the police be doing this?"

"Should, maybe. Don't."

"That's because they keep getting their budget cut. They don't have the personnel to keep someone out here when nothing's going on."

"Maybe nothing's going on 'cause we're here."

"Maybe," Richie admitted. "But if the residents here paid what they're shelling out to Rampart as taxes, the PD could assign someone to regular patrols."

"Wouldn't be me," Kevin said.

Not me, either, Richie thought. There's the problem with that scenario.

"You don't want your job," Kevin said, "there's other folks would like it."

"I'm not saying that. It's fine. It just seems strange, is all."

Richie did not, in fact, want the job. But it was work, and for the past thirteen months, since being fired by the PD, the only employment he had been able to find had been a swing shift stint at an Arby's and a broom jockey position at the Fairlane Town Center in Dearborn, where people had looked at him, if they noticed him at all, as if he'd been a curiously colored centipede. He took those jobs because he and Wendy needed the money, same reason he had taken the spot at Rampart. All he had ever wanted was to be a cop, and having failed at that, he was without a goal, as lost in his own life as a traveler without a map.

Having come perilously close to upsetting his supervisor, whose reports to management would determine how long he remained on trainee status, he went for a quick change of subject. "Hey, on my way to work tonight I caught a kid trying to break into a vacant with a crowbar."

"What'd you do?"

Richie told him the story, describing the house, Wil, the abbreviated chase, and Wil's surrender.

"Where'd you say that house was?" Kevin asked when he finished.

Richie had described the location, but he did so again. Kevin, like other lifelong residents of the city, imagined they knew every house. "It's on the northwest corner of Longfellow and Fourteenth," Richie said. "A couple blocks from my new place."

"No shit?"

"What?"

"You know what house that was, don't you?"

"Is it famous?"

"Ever hear of Angela Morton?"

Richie knew the name. He studied crime like some people did baseball stats, and this one had been big news. "That little girl who was abducted, what, ten years ago or so?"

"Little more, I think."

Richie remembered the broad strokes, if not the fine details. A young girl had been snatched, apparently from her front yard. No ransom demand had ever materialized. Neither had a body. It had been front-page news for a few weeks, the lead story on the evening news, and then it had tapered off. There had never been an arrest. "Was that her place?"

"Northwest corner, right? Big ol' tree in the front?"

"That's right."

"My momma was obsessed with that case. She cut out newspaper clippings, watched everything on the TV. She used to drive me and my sister by that house and shake her head and tell us never to talk to strangers."

"Thirteen years," Richie said.

"Say what?"

"It was thirteen years ago. I can't remember her parents' names, but I do remember that."

"Damn."

"Crime's kind of a hobby of mine. Learning about it, not doing it."

"Good thing."

"Wow." Richie shook his head. "That was the Angela Morton house. I never put that together before. Trippy."

"Was a long time ago," Kevin said.

"Thirteen years."

"Yeah."

"Poor kid."

"You think she's dead?"

"Of course she is. People who take kids like that, without asking for ransom, almost invariably do it for sex. Most of their victims are dead in twenty-four hours. Less than. Just…"

"Just what?"

"Well, Wendy and I are trying to have kids. Makes you wonder. What if the bastard who took Angela Morton still lives in the neighborhood?"

Kevin made a right turn, driving slowly past the big, expensive homes. "Then," he said, "you better figure out who it is. And right quick."