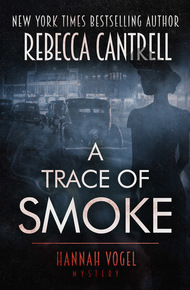

New York Times and USA Today bestselling author Rebecca Cantrell has published twenty-two novels that have been translated into several different languages. Her novels have won the ITW Thriller, the Macavity, and the Bruce Alexander awards. In addition, they have been nominated for the GoodReads Choice, the Barry, the RT Reviewers Choice, and the APPY awards. She lives in Hawaii with her husband, son, and a slightly deranged cat named Twinkle.

***Winner of the Macavity and Bruce Alexander Award!***

It's 1931 in Berlin, and the world is on the precipice of change—the affluent still dance in their gilded cages but more and more people are living under threat and poverty. Hannah Vogel is a crime reporter forced to write under the male pseudonym Peter Weill. As a widow of the Great War, she's used to doing what she must to survive. Her careful facade is threatened when she stumbles across a photograph of her brother in the Hall of the Unnamed Dead. Reluctant to make a formal identification until she has all the details, Hannah decides to investigate, herself. She must be cautious as Ernst's life as a cross-dressing cabaret star was ringed in scandal, and his list of lovers included at least one powerful leader in the Nazi party.

She's barely had a chance to begin before an endearing five-year-old orphan shows up on her doorstep holding a birth certificate listing her dead brother Ernst as his father, and calling Hannah 'Mother.' Further complicating matters are her evolving feelings for Boris Krause, a powerful banker whose world is the antithesis of Hannah's. Boris has built a solid wall preventing anyone from disturbing his, or his daughter Trudi's, perfectly managed lives—a wall Hannah and Anton are slowly breaking down.

As Hannah digs, she discovers political intrigues and scandals touching the top ranks of the rising Nazi party. Fired from her job and on the run from Hitler's troops, she must protect herself and the little boy who has come to love her, but can she afford to find love for herself?

I discovered Rebecca Cantrell's work at a Borders bookstore one evening while browsing the shelves. Some marvelous bookstore employee had turned A Trace of Smoke face out. I grabbed a copy, read the opening lines, and got hooked. Now, I find myself waiting breathlessly for each Hannah Vogel mystery. Becky writes 1930s Europe so vividly I feel like I've traveled there. Which I guess I have—courtesy of Rebecca Cantrell. – Kristine Kathryn Rusch

"Bold narrator and chilling historical setting...an unusually vivid context, [lets] Hannah report on the decadence of her world without losing her life –or her mind."

– New York Times"Nails both the 'life is a cabaret' atmosphere and the desperation floating inside the champagne bubbles."

– Booklist"The playful, but also despairing, decadence of Weimar Berlin, captured vividly by…Ms. Cantrell."

– Wall Street Journal"It's dark, it's dangerous, it's bittersweet and while I was reading it, I couldn't put it down."

– dearauthor.com"Evocative and hauntingly crafted...a treasure of suspense, romance, and murder. Her ability to spin history into a visceral reality is done with the artistry of a master storyteller."—

– James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of The Seventh Plague"A compelling and human story that captures brilliantly the atmosphere of Berlin during the rise of the Nazis."

– Anne Perry, New York Times bestselling author of We Shall Not Sleep"Riveting from page one, Rebecca Cantrell's A Trace of Smoke is a compelling mystery set amid the decadence of 1930s Berlin."

– Rhys Bowen, author of the Molly Murphy and Constable Evans Mysteries1

Echoes of my footfalls faded into the damp air of the Hall of the Unnamed Dead as I paused to stare at the framed photograph of a man. He was laid out against a riverbank, dark slime wrapped around his sculpted arms and legs. Even through the paleness and rigidity of death, his face was beautiful. A small, dark mole graced the left side of his cleft chin. His dark eyebrows arched across his forehead like bird wings, and his long hair, dark now with water, streamed out behind him.

Watery morning light from high windows illuminated the neat grid of black-and-white photographs lining the walls of the Alexanderplatz police station. One hundred frames displayed the faces and postures of Berlin's most recent unclaimed dead. Every Monday the police changed out the oldest photographs to make room for the latest editions of those who carried no identification, as was too often the case in Berlin since the Great War.

My eyes darted to the words under the photograph that had called to me. Fished from the water by a sightseeing boat the morning of Saturday, May 30, 1931—the day before yesterday. Apparent cause of death: stab wound to the heart. Under distinguishing characteristics they listed a heart-shaped tattoo on his lower back that said "Father." No identification present.

I needed none. I knew the face as well as my own, or my sister Ursula's, with our square jaws and cleft chins. I wore my dark blond hair cut short into a bob, but he wore his long, like our mother, like any woman of a certain age, although he was neither a woman nor of a certain age. He was my baby brother, Ernst.

My fingertips touched the cool glass that covered the image, aching to touch the young man himself. I had not seen him naked since I'd bathed him as a child. I pulled my peacock-green silk scarf from my neck to cover him, realizing instantly how crazy that was. Instead, I clenched the scarf in my hand. A gift from him.

I knew standard procedure dictated the body be buried within three days. It might already be in an unmarked grave, wrapped in a coarse shroud. After Ernst left home and started earning his own money, he swore only silk and cashmere would touch his skin. I flattened my palm on the glass. The picture could not be real.

"Hannah!" called a booming voice. Without turning, I recognized the baritone of Fritz Waldheim, a policeman at Alexanderplatz. A voice that had never before frightened me. "Here for the reports?"

I drew my hand back from the photograph and cleared my throat. "Of course," I called.

My damp skirt brushed my calves as I trudged down the hall to his office in the Criminal Investigations Department, struggling to bring my emotions under control. Feel nothing now, I told myself. Only after you leave the police station.

Fritz held the door open, and I nodded my thanks. He was the kindly husband of my oldest friend, and I feared he would recognize the photograph too, if he studied it closely. He must not suspect Ernst was dead. My identity papers, and Ernst's, were on a ship to America with my friend Sarah and her son Tobias.

Sarah, a prominent Zionist troublemaker, was forbidden to travel by order of the German government. Ernst and I had loaned Sarah and Tobias our identity papers so they could masquerade as Hannah and Ernst Vogel, a German brother and sister on vacation. Their ship would dock soon, and our papers would be returned, but until that happened no one could notice anything Hannah and Ernst Vogel did in Berlin without placing their lives in danger. Even though Ernst had acted distant with me recently, he had agreed to the plan.

"Still raining, I see." Fritz pointed to my dripping umbrella. I'd forgotten I still held it. He closed the office door.

"Washes the dog shit off the sidewalks." My forced laugh tore my heart. The weather remained our favorite joke, Fritz and mine. We jested about that and his Alsatian dog, Caramel.

"How are Bettina and the children?" I tried to always keep it light. To make him enjoy handing me the police reports so much it did not cross his mind that he did not need to do it.

"Are you crying?" he asked, concern in his gray eyes. No getting past Fritz, the experienced detective.

"A cold." I wiped my wet face with my wet hand. I hated to lie to him, but Fritz ran everything by the book. He would neither understand, nor forgive, passing off my papers, even to save Sarah. "A cold and the rain."

He took a clean, white handkerchief out of his uniform pocket and handed it to me. It smelled of starch from Bettina's wifely care. "Thank you," I said, wiping my cheeks. "Anything interesting?"

Like every Monday, I had come to the police station to sift through the weekend's crime reports in search of a story for the Berliner Tageblatt, looking for a tale of horror to titillate our readers. Mondays were the best times for fresh reports. People got up to more trouble on weekends, and at the full moon. Ernst's photograph flashed through my head. He too, had got up to more trouble on the weekend. I swallowed my grief and handed Fritz his handkerchief.

"We found a few floaters last weekend." He walked behind the wooden counter that separated his work area from the public area. "Mostly vagrants, I think. Probably a few from a new power struggle between criminal rings, but we'll not prove it."

I held my face stiff, using the polite smile I'd mastered as a child. I was grateful for the beatings, slappings, and pinchings I'd received from my parents. They taught me to hold this face no matter what my real thoughts and feelings. Ernst had mocked me for it. Everything he thought or felt showed on his face the instant it entered his head. And now he was dead. I gulped, once more fighting for control. Fritz furrowed his brow. He suspected something was wrong, in spite of my best efforts.

"Anything worth my time?" I said to Fritz, because that is what I would have said on any other day.

"A group of Nazis beat a Communist to death, but that's not news."

"Not news. But newsworthy, even though the Tageblatt will not run it. Someone should care what the Nazis are doing."

"We care. But the courts let them go faster than we can arrest them."

He turned and walked to a large oak file cabinet. As he sorted through folders I took a steadying breath.

"Here we go." He pulled out a stack of papers.

I leaned against the counter and tried to look composed.

Fritz passed me the incident reports with his short, blunt fingers. "Not much, I'm afraid."

"Hey!" called a high-pitched male voice behind Fritz. "You must not give her those reports." A man with erect military bearing rushed over to us and snatched the papers from my hand. "Who are you?"

Fritz looked worried. "She's Hannah Vogel, with the Berliner Tageblatt."

"You have identification?" His dark crow's eyes studied me. His thick black hair was perfectly in order, his suit meticulously pressed.

"Of course." My identification rested in Sarah's purse on a boat in the middle of the ocean. I rummaged through my satchel, for show, grief replaced again by fear.

"I've known her since she was seventeen years old," Fritz said.

The man ignored him and snapped his fingers. "Papers, please."

"They must be here somewhere." My knees threatened to collapse. I took things out of my satchel: a green notebook, a clean handkerchief, a jade-colored fountain pen Ernst bought for me after he left home.

"What do you do at the Tageblatt?" His tone sounded accusatory. He leaned closer to me. I yearned to back away, but forced myself to remain still, like someone with nothing to hide.

"Crime reporter," I answered, looking up. "Under the name of Peter Weill."

"The Peter Weill?" His tone shifted. He was a fan.

"For the past several years. I have worked closely with the police all that time."

I pulled my press pass out of my satchel and handed it to him, then flipped open my sketchbook to a courtroom sketch published in the paper a week ago.

His face creased in a smile. "I remember that picture. Your line work is quite accomplished." He returned my press pass, and I tucked it into my satchel.

"It's so rare anyone notices. You have a discerning eye."

Fritz suppressed a smile when the man stood even straighter and held out his hand.

"Kommissar Lang."

I wiped my palm on my skirt before shaking his hand. "Good to meet you."

"The pleasure is mine." He rocked back on the heels of his highly polished shoes. "Your articles have astute insight into the criminal mind. And the measures we must take in order to protect good German people from the wrong elements."

"I try to do a good, fair job by getting my information from the source." I glanced at the reports in his hand.

He bowed and handed them to me. "So many reporters these days speak only to victims. Or criminals."

"They are important sources as well." I took the reports with a hand that trembled only slightly. "One must be thorough."

"You have such insight into the male mind. You and your husband must be close."

"She's never been married," Fritz said. The corners of his mouth twitched with a suppressed smile.

"Might you autograph an article for me?" Kommissar Lang clasped his hands behind his back and leaned forward. "Do you have an article in today's paper?"

I had not yet read today's paper. "I am not certain."

"Yesterday's," Fritz said. "Front page."

"I will procure a copy." Kommissar Lang hastened out of the room. Fritz returned to his desk without saying a word. His shoulders twitched with laughter, but he kept a serious face. It cost me, but I gave him the expected warning smile.

When I glanced at the reports, I saw gibberish. Lines of black type ran along the paper, but my mind could not turn them into words. My hand shook as I pretended to take notes, but I hoped Fritz could not see that from his desk. I willed myself to think of nothing but numbers and stared at the second hand of my watch, silently counting each tick. When three minutes elapsed, I put the unread reports on the counter. "You are correct, Fritz. Not much there."

I would find no report of a sensational murder or string of robberies for Peter Weill's byline today. And the murder I most wanted to research I could not ask a single question about. No attention dared fall on Ernst or me. If Sarah and her son were still underway, they might be arrested. Because of her political activism, she had been denied immigration to the United States three times.

It was becoming harder for even apolitical Jews to leave Germany. If the National Socialists, the Nazis, were to gain the majority in the Reichstag, I shuddered to think what would happen. As disgusting as I found it, I had to admit Hitler was far too clever at using it for his political ends. Things would get worse before they got better.

I turned and marched back down the hall, willing myself not to glance at the photograph. If I did not look, perhaps it would not be true.

"Fräulein Vogel," called Kommissar Lang. I heard him sprinting after me.

Something was amiss. Would he demand to see my papers again, papers I still did not have? I envisioned bolting through the front door of the police station, but instead I turned to him, ready to concoct a story of lost papers.

"You forgot my autograph," he panted.

"I do apologize." Relief flooded over me. "It slipped my mind. I am so late for the Becker trial."

"The rapist who targeted schoolgirls in the park?"

"That one." Any other day I would have asked him about his involvement in the case, but today I needed to get away before I broke down.

He thrust the paper at me.

"I apologize in advance if there's anything inaccurate. My editor has a leaden touch."

He handed me a pen. "Come to my office and sign it." He gestured back down the hallway, past the photograph of Ernst. If I followed him, I knew he would regale me with tales of his arrests and later be offended that I did not write each one for the Tageblatt. I had been through that with countless police officers, and afterward they were never much use as sources.

I placed his newspaper against the wall and signed it. "I must be at the courthouse early. It is best to watch the accused come in and sit down. One learns so much."

"One can determine a great deal from watching someone walk."

I handed him back the newspaper and walked out the front door, trying not to let the wobble in my knees betray me.

Outside, a gust of wind tried to rip the umbrella out of my hands, but I held on, cursing and half-crying as I stumbled across cobblestones to the subway. I pushed my way down concrete stairs, against the crush of people going to work. They chattered and laughed together, gleeful in the mundane details of their lives. I wanted only to go home and be alone.

Pictures of Ernst flashed by in my head. The most painful images were from his childhood. He'd been a wonderful child and, later, a great friend. I leaned against the wall of the subway station, face turned toward the tile, and sobbed, safely alone in the crowd. When I could stand and walk again, I did.

Once aboard the train I collapsed on the wooden seat and drew a deep breath. I ran my fingertips over the oak slats of the bench. The wood was blond, like Ernst's hair. Across from me, their faces hidden behind twin newspapers, sat two men in black fedoras. One man read the Berliner Tageblatt, the other the Völkische Beobachter, that Nazi rag.