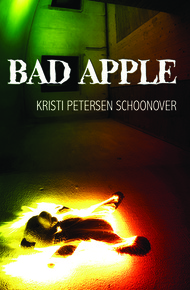

Kristi Petersen Schoonover’s novel, Bad Apple, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her short fiction has appeared in countless magazines and anthologies; she has received three Norman Mailer Writers Colony Residencies, has served as a judge for New York City Midnight's short story competitions, and is a co-founding editor at Read Short Fiction. She spent her childhood autumns apple picking, lives with her husband, occult specialist Nathan Schoonover, in the haunted woods of Connecticut, and still sleeps with the lights on. You can find out more at her website.

After an unfortunate incident on a Maine apple orchard, precocious teen Scree is left with a father she’s not sure is hers, a never-ending list of chores and the raising of her flaky brother’s baby. In a noble move to save the child from an existence like her own, Scree flees to a glitzy resort teeming with young men just ripe for the picking. But even as life with baby becomes all she’d dreamed, Dali-esque visions begin to leach through the gold paint… In the tradition of Shirley Jackson, Bad Apple is a dark, surreal ride that proves not all things in an orchard are safe to pick.

"A brilliant first novel with a highly emotional sense of dread and unease throughout the tale that concluded with one of the best endings of the year."

–Peter Schwotzer, Literary Mayhem"The author has a great sense of voice…psychological horror at its best."

–Brady Allen, author of Back Roads and Frontal Lobes"Deeply disturbing in the best way possible. These characters screamed for a witness, and I was helpless against them."

–Zombrarian, SciFi Saturday Night"Drags the reader in and keeps its claws fastened long after he’s put it down."

–Philip Perron, Dark Discussions Podcast"...a page-turner."

–Stacey Longo Harris, owner Books & BoosScarborough. That’s my name. Yes, I know that’s an uncomfortable name for a girl; my cousin told me I was named for the state’s racetrack. "That’s dumb," she said.

"Not as dumb as you," I countered. I knew her Meemom didn’t do word-a-day flashcards with her during breakfast, didn’t encourage her to use words like acerbic in sentences while she did her chores, and didn’t make her read thick books without any pictures. But then my cousin passed me a sun-faded postcard she’d found in one of Meemom’s dilapidated trunks in the attic: on the front, an alpine-styled hotel room with red satin bedspreads and cut-outs of pine trees on the headboards. "Nothing beats the Towers Hotel! Our elegant Sky-High Cocktail Bar offers Happy Hour against gravity-defying views of Scarborough Downs and the city of Portland." On the back, her spider-script noted she was having a "great time at the track betting on the horses with"—a name that didn’t belong to my father.

Well, a name that didn’t belong to the man I assumed was my father. I don’t think he was around before I started walking, and I associated him with my first day at kindergarten. He would sit at our kitchen table—a door slapped across two stacks of cinder blocks—in the same pair of jeans and T-shirt he’d arrived in the night before, and he’d say things to Meemom like he should move in and take over running the business end of the orchard. When he did what he said, I assumed at the time he must be the one. But after I saw the postcard, which was dated about nine months before I was born, I wasn’t sure. I, therefore, couldn’t think of a suitable retort for my cousin, so I just crumpled the postcard, rammed it into my pocket, and demanded she go home. But it wasn’t over, because from that moment, I was uncertain where I really came from—well, except from Meemom’s birth canal.

So half of me was missing, and my special name wasn’t a substitute. I was not a Jane or an Erika or one of the five Marys in my kindergarten class. The big boys picked raisin-fat boogers from their noses, smeared them on their pants and jeered, "Look, it’s the Scar! The Human Scar!" As they got older and about as clever as their genes were ever going to allow them to get, they got creative and put a "y" at the end, as in, "Oh, you’re so scary! Scar-y Scar!" Which goes to show you how stupid they were, because my nickname is Scree.

When I got older, I thought about those boys a lot. If they’d ever procreated like Meemom and whoever; if they’d be in sticky bars, swilling beer and hoping to cop a feel; if they’d have enough money in their fake alligator wallets to get some unfortunate girls—who had probably begun the night with handbags full of high hopes—drunk enough to engage in sex in the back seats of their cars.

I didn’t know anything about sex when I was that age, but I did know about orgasms: Hush-hush was what I called it, and I thought of it as a game of sorts—I didn’t have my first one with a boy; I had it with a stuffed bear that Meemom had saved her pennies to buy me one Christmas.

I had seen that bear in Pinky’s Toy Barn; it had been made by the woman who lived on the hill above our orchard, and its fur was as downy as the chicks we used to have when our coop was still up and running.

We used to go to the county fair every August and bring home a few chicks; Meemom always bought them to try to teach my brother, Arable, responsibility. And he was good and upstanding and oh so responsible. He really was. In a month or so, the puffballs blossomed into spiteful Rhode Island Reds or Naked Necks. Until they got too big, Arable let me pet them. Even though they smelled and shit everywhere, they were my little friends. But then Arable had a fight with Meemom and moved out. When Meemom heard he’d shacked up with the antique store owner’s daughter in a motel cottage on the other side of town, she stopped buying chicks. I begged and pleaded, but she just wouldn’t do it. I missed them; I was friendless.

So I wanted that bear—but I never asked. I think Meemom just must have cocked an eye toward me at that certain moment, saw me stroking the bear’s fur, saw me lifting it off the shelf and crushing it against the splotchy pink birthmark on my neck, and made a deal with the woman to give it to me eight months later under the Christmas tree—just an evergreen we sawed off down the back lot. And when I got Bear, I discovered how it felt when I rubbed it back and forth between my legs while I lay on my daisy-splattered bedspread. I heard the tee-hoo, tee-hoo songs of the chickadees outside my window that spring; I inhaled the smell of our apples in the orchard that fall; I sweated in the thick fireplace heat that winter. Bear and I became best friends.

Until one July 10th. The land seared under a broiler sun: The back row of the orchard’s trees—the ones that got the least attention from the Columbus Day hordes—suffered; everything was so dry the tufted grass between the trees had crisped to shredded wheat, and the tent caterpillars, failing to complete their shrouds, were curled cinders at their trunks.

The stone well was out back by those trees, and it had kept us in water for most of my life. It had a forlorn, but beckoning quality, because the man I came to recognize as my father had spent so much time making it into the stuff of happy endings: He was particularly dexterous, so he made an A-frame roof for it, complete with a dowel for the water bucket; in the slope of the roof, he carved out a star. He said the star was for Meemom, because she was more beautiful than his favorite constellation, Cassiopeia. He’d shown me the upside-down queen once up in her smear of milk in the sky, but after that night, I always had trouble finding it again.

I loved that well, but I loved it more in that strange, dry summer, because there was no water in its belly, so I could call my name into it, a sing-song "Scar-borough." The echo of it bouncing back at me was that missing half of myself weltering up from the darkness.

That summer before first grade, Bear went with me everywhere, including to the well on that searing July 10th. I had just finished my morning hush-hush and consumed my usual cinnamon bun, and I explained that the word of the day was precarious as I clutched him under my arm and went out to the well to find myself. But I leaned so far over in straining to see the puzzle of bricks laddering up the sides, Bear fell in. Bear fell in! Not a thunk or a splash or anything, just down he went like a plummeting chestnut, and he was gone. Gone!

My mouth erupted in screams as curdling as the day the hornets had chased me from the wild blueberries; my pumping knees and green shorts were smeared with grayish dirt. "Meemom!" I was crying, but it was so dry, I wasn’t making tears.

Meemom burst from our flimsy screen door, her red hair flying behind her like the ribbons of so many kites. She swept me into her arms.

"Bear fell in!" I wailed, and she set me back down again and touched my cheek. She wasn’t going to say, "We’ll get you another," because even if the lady had fashioned another with chick-like fuzz, it would not be Bear, and Meemom was not a parent who doted; she expected me to know the value of things, to treat something hard-won with respect. She fumbled in the pocket of her spattered apron to bring up a dusty blue tissue, held it to my nose, and told me to blow. I did, but not too hard—I didn’t want her to see certain things that came from my body.

"What were you doing up there by that well? That’s very dangerous, Sweet Bread," she said.

I couldn’t tell her about the part of me I believed was cowering in the bottom of that well, because she would try to take it from me, ask me, perhaps, why I would believe in such things, or flat-out instruct me in the ways of science with regard to the human voice. "An echo is not the shadow side of who we are," she might say, "but who we actually are coming back at us." Then, under the auspices of her pitying expression, I would have to finally accept the fact that the half of me that was missing, the half of me that I’d been looking for since my dawn of awareness, would elude me forever. So instead, I cried some more, and she stood up, seized my hand, and led me back up the long hill; when I tried to pull away from her, I was stuck to the melted brown sugar on her palm.

The well’s opening glowered. Meemom let go of me and stood for a moment, straightening her back; she had a focused look I had seen once on the trapeze man at the circus. Then, she stepped forward, braced her hands on the wall of the well, and peered in. "Bear!" she chimed. "Bear, little Scree is worried about you! Are you okay down there?"

I was old enough to understand Bear really didn’t talk. He was my best friend, so if he could’ve, he would’ve talked to me. But at that moment, knowing Bear was down there, all hurt and cold and scared, I suddenly feared he might be able to, to cry for help—maybe he could always talk and didn’t have reason to before this. Or maybe he had just needed Meemom to call him. Maybe she even had always known he could talk, and maybe she’d just assumed he talked to me, too. So I cocked my ear and listened for something, anything—a hiccup, yelp, or growl.

Then I was struck with the thought that maybe it wasn’t a good idea that Bear talk to Meemom. Suppose he told her about hush-hush! Hush-hush was private; it was bad. I would be paddled. Perhaps even banished.

"Suppose he tells her about hush-hush," whispered the well.

Meemom whirled around.

"He says he’s okay," she said. Then she tilted her head. "What was that you said, Bear?" She shook off her dainty, pink slippers, stepped stone by stone onto the ledge, and kneeled. I couldn’t see her head anymore, just the feline hunch of her back, the seat of her dress, and the dirty bottoms of her bare feet. "What did you want to say to me?"

Oh no. He was going to tell her! I leapt forward, yawping wildly to cover any answer he might emit, and I crashed into Meemom.

With a shriek that echoed all the way down, she was gone. Crunch-crack.

My insides pinched in the grip of something worse than getting caught for throwing rocks at the Booger Boys on the playground. Oh, this was worse, so, so much worse. I waited for her to call up to me, to say it was okay, she knew it was an accident, and when her voice didn’t come, the talons of her angry spirit shredded my guts into vomit on the grass. She was going to punish me forever, because I was guilty, guilty, guilty, and these were the words from my flapping mouth: "Meemom, I threw up, I want you Meemom, I’m sorry, Meemom, I didn’t mean it, come back, I swear I just didn’t want you to hear, I didn’t want you to know because you’d go away from me…"

Then, there was the soreness of what was no more. No more love, no more warmth, no more cinnamon buns, no more lily perfume, no more bedtime art book stories. No more word-of-the-day. No more picking wild blueberries. No more. No more Meemom.

"Meemom!" I leaned over and hollered.

But all I heard was the echo, that missing half of me that I suddenly no longer wanted to find, because she was very, very ugly.