Jody Lynn Nye is a writer of fantasy and science fiction books and short stories.

Since 1987 she has published over 45 books and more than 150 short stories, including epic fantasies, contemporary humorous fantasy, humorous military science fiction, and edited three anthologies. She collaborated with Anne McCaffrey on a number of books, including the New York Times bestseller, Crisis on Doona. She also wrote eight books with Robert Asprin, and continues both of Asprin's Myth-Adventures series and Dragons series. Her newest series is the Lord Thomas Kinago adventures, the most recent of which is Rhythm of the Imperium (Baen Books), a humorous military SF novel. She also runs the two-day intensive writers' workshop at DragonCon.

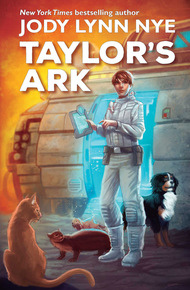

Her other recent books are Myth-Fits (Ace Books), Wishing on a Star (Arc Manor Press); an e-collection of cat stories, Cats Triumphant! (Event Horizon); Dragons Run (fourth in the Dragons series) and Launch Pad, an anthology of science fiction stories co-edited with Mike Brotherton (WordFire). She is also happy to announce the reissue of her Mythology series and Taylor's Ark series from WordFire Publishing. Jody runs the two-day intensive writers' workshop at DragonCon, and she and her husband, Bill Fawcett are the book reviewers for Galaxy's Edge Magazine.

Bill Fawcett & Associates has packaged over 350 books science fiction, fantasy, military, non-fiction, and licensed novels and series for major publishers. As an author Bill has written or co-authored over a dozen books plus close to one hundred articles and short stories. Bill has collaborated on several mystery novels including with Chelsea Quinn Yarbro including the Authorized Mycroft Holmes novels. As an anthologist Bill has edited or co-edited over 40 anthologies.

Dr. Shona Taylor, a specialist in environmental medicine, discovers that a mysterious epidemic is killing the entire population of colony worlds. With the help of her special menagerie, including a cat that can detect environmental hazards, a dog whose system can synthesize vaccines, and an intelligent alien named Chirwl, Shona is determined to stop the epidemic in its tracks, but the people causing the epidemic have set her up to take the blame, spreading the rumor that she is an Angel of Death. Can she find a cure before the disease kills again and puts her and her menagerie in danger?

"Exciting… enjoyable space adventure… Taylor's Ark is fun and well-crafted, with a heroine you'll enjoy rooting for!"

– Aboriginal SF"A standard Jody Nye space opera. Enjoyable start to finish. You'll want to read both books."

– Amazon ReviewThe great colony ship stood on the launch pad, looming unconcerned above the whirl of preparation which went on around its base as its crew made ready to board. The shimmering vessel was one of the vast fleet used by the government of the United Galaxy to convey pioneer settlers from Marsbase, in the Sol system, to their designated planets. Its cluster of cylinders joined by buttresses and braces looked gothic and ornate, but were actually functional conduit and passageway. Through the smoke-tinted atmosphere dome above it, the two small moons of Mars, Deimos and Phobos, were visible, racing one another across the sky. The ship's current complement of colonists were bound for the outer reaches of Twelfth Sector, beyond the current perimeter of UG space. Because half of the ship's yearlong trip would carry it away from the last available repair facility, it needed to be as self-reliant and as immune to incapacity as human technicians could make it. Rigorous inspections had been carried out and double-checked. Most of the loading was complete. The last items to go on were the small containers of personal possessions, intended to make the long journey more comfortable and lend a touch of civilization to the colonists' new home.

The colony leader, a tall, rawboned woman clad in the thin metallic weave of a pressure suit, watched the wheeled loaders with a careful eye. She winced as one of the polygonal boxes missed the hatch and slammed against the side of the vessel. "Clumsy louts. It's enough to make my blood pressure skyrocket." She glanced at the medical technician who was examining her. "Off the record of course."

"Of course! Raise your arms, please." Dr. Shona Taylor, a cheerful young woman of twenty-six, prodded the captain's elbow with a small piece of medical apparatus, urging her to raise her arms above her head. She was the physician assigned to the colony until it lifted off. Her job was to make certain the crew was as ready as the ship for its long and rigorous journey. Shona held the device a few inches from the woman's rib cage and walked around her.

"Good thing we're getting out of here today," the captain said. "If anyone pokes any more holes in me, I'll leak."

"This is the last, I promise you. I'm just getting one final check in before you seal the hatch." Electrocardiogram normal, electroencephalogram within normal range, resting pulse low, Shona noted, and check, check, check on the rest of the captain's metabolism.

"I'm curious," Shona said, glancing at the businesslike crew around her. She was interested in what made people tick. "Your settlement party is composed entirely of women. That's an unusual choice."

"It's our contention that an all-woman colony gets along better than one that's co-ed or all male," the captain said firmly. "Because of the climate and wildlife on the planet we're taking, we need to stay a sisterhood as tightly knit as we can make it. Each of us must be prepared to take charge if necessary. If we don't, we won't survive. I don't want to have a dominance battle with a man who attempts to take over the whole settlement and run things his way. Our shrink interviewed a lot of people. A lot of good technicians and admin people didn't make the cut because they couldn't function under the circumstances we'll be facing. We managed to convince the government that the colony would function better for us this way. One little thing could undo all our careful work. Someone who complains too much, one with pernicious body odor, one with annoying nervous habits—that could kick us all over the edge if we're forced to hole up and hibernate together over the winter season. I can't afford to take that risk."

It was true. The makeup of a colony was a very personal and particular thing. It took the vision of an individual, who usually became colony leader, to design a worldview that would hold together for the initial months of settlement, the most difficult phase to survive. Once the colony was well-established, things might change, but for the early stages it was vital that it follow one plan, one direction. Once the delivery vehicle left atmosphere, the group was on its own. Shona remembered that on her second mission, the group was a patriarchy. The colonists were all related to one another, and led by an irascible old man who was the descendant of a hundred generations of cotton farmers on Earth. The government had assigned them a planet to raise cotton and silk, lucrative cash crops. The Cotton Consortium had even legally adopted enough babies of both sexes to grow up to be spouses to the current infants in the family. That was carrying unity pretty far, Shona had thought, but that settlement had been as closely woven as a piece of its own fine percale cloth. The mission specialists were the only outsiders in the group, and treated as such. Shona was sure if it had been her first mission, she might have taken such destructive treatment personally. As it was, the botanist with them nearly went crazy. Shona and one of the others had to be with the woman at all times, fearing a suicide attempt. They had been grateful and relieved when the retrieval ship came for them at the end of six months. Some of the colonists they left behind were also showing signs of strain under the autocratic rule of their leader, but the ones who survived would prosper and do well. Shona expected to hear about the richness of that settlement for generations to come, and of this one.

"Naturally that brings me to the next question," Shona asked. "How do you plan to …"

One corner of the captain's mouth went up. Shona guessed she had answered the same query a hundred times over the last months. "Propagate the species? Well, you might have noticed that about half my settlers are already carrying. Then there's that." She gestured toward one of the vast modules with a "Science" designation being loaded into the rear cargo bay. "Zygotes, to be implanted in utero. Very safe, relatively foolproof. As we come to need greater population growth, some of us can carry a few at a time, instead of one. After that, it's cell-implantation in egg nuclei. Healthy, and always XX. I might carry another or so myself, if all goes well."

"But what about the male zygotes?" Shona said, a horrible thought suddenly striking her.

It must have shown in her face. "Oh, we just don't use them," the captain said, shrugging. "Analysis of one cell tells you what you've got before you'd do anything irrevocable with it. We'd never destroy them. We just don't use them. Want a few XY zygotes? Guaranteed healthy genes. No charge."

"No, thanks," Shona laughed, pointing to her midsection, which bulged against the fabric of her environment suit. "My husband and I prefer to start them the old-fashioned way."

"Boy or girl?" the captain asked, with friendly curiosity.

"Don't know. I'm letting it be a mystery," Shona said, her eyes alight. "I've delivered a lot of babies, but I've never had one before. I want this to develop slowly, so I can enjoy it."

"No morning sickness," the other woman deduced sagely. "Well, I've had five girls, and been sick as heck every time."

Shona made some notes on her clipboard. "I saw your girls. They're adorable." Satisfied by the readings on the whirring device, Shona nodded to the captain to lower her arms. "Good."

"How am I, Doctor?"

"You're in fine shape," Shona said, her wide mouth stretching into a smile. "Same as always. Your circulatory system is strong. That's important when you're going to spend a lot of time in zero gee. Don't forget to keep taking your calcium and magnesium."

"I already take so many tablets I rattle!" The captain's retort was followed unexpectedly by a loud vibration and a bang that made both women look around in surprise. Beside the ship, the skid loader had turned over on its side, spraying packages and boxes halfway across the loading dock. A carton slid to a halt at their feet. The captain's face flushed angrily. "Burning stars, I told you idiots to watch it!"

"Someone's hurt," Shona said, seeing an outstretched hand behind the upturned fins of the loader and the heap of containers. She gathered her medical gear up and hurried over. The captain followed, loping in her heavy boots.

Shona ignored the argument starting behind her back between the captain and the loader operator, and pushed through the crowd that was gathering around them. There was a woman on the floor half-buried by the boxes. The doctor dropped to her knees and helped the crew uncover her. Shona could tell immediately by the angle of the woman's leg that it was broken. Gently, she probed through the soft metallic fabric of the suit leg and found the place where the bone had snapped. The flesh around it was already beginning to swell. Her patient sat up, her brown-skinned face hollow with shock.

"Is it broken?" she asked.

Shona nodded. "Clean snap, I think. Do you want a painkiller?"

"No—no," the woman said. "Clouds the mind. I'll be all right. I'd rather know what's going on. I'm the colony doctor."

"Were, I'm afraid," Shona said, unsealing the suit seams and pushing the folds of silver-white cloth aside to examine the woman's thigh. The deep blue-blackness of edema had begun to color the flesh. "I can't let you go like this. I need to image this, set it, and get you into a cast pronto. You'll be on your back for weeks."

"Please, Doctor," the captain said, hearing Shona's reply. She turned away from her argument and dropped down beside them. "You can't take her off assignment. Muñoz is our GP. We can't leave her behind. Without her, we're below the minimum med staff level."

Shona considered, drumming her fingers on her own leg. "When do you lift off?"

"About an hour. There was a delay in getting supplies from one of the private companies. That's not much of a window, but there's a Corporation colony leaving an hour behind us. If we miss the slot, it may be weeks before we leave, and we could arrive too late to put in a first crop. That could convince the bureaucrats to turn the whole place over to the GLC." Without that crop it was likely a new colony would be unable to afford the things it would need to thrive later, or maybe survive at all. If this was to be the case, the colony could lose its charter before they had even left.

A small silence fell between them as each assessed the other's possible reaction. Where the government ships carried the bare necessities for the comfort and entertainment of its employees for the long hauls, the GLC ships were lushly outfitted, featuring game rooms, fresh-food storage, and other enviable amenities. The Galactic Laboratory Corporation supplied through itself or its many subsidiaries nearly every commodity or service money could buy. The GLC was the government's partner and rival in the space race, often claiming systems right under the government's nose, and occasionally settling personnel on the same planet. Rumor was that armed skirmishes had broken out on some of those invaded worlds, but no reports had ever come back to substantiate it. Because of the Corporation's careful demonstration of propriety in matters of charity and endowments, the public tolerated its bendings of the system, but in private some citizens felt that it was high-handed and abusive, writing its own versions of the law. Though almost half the population owned a few shares of the giant corporation's stock, few people felt comfortable voicing that sentiment aloud. The Corporation seemed to have ears everywhere, and its influence was powerful. Its all-round utility gave it leverage.

Their colonies were not intended, as government settlements were, to operate independently as sovereign worlds each with its own economy. Each had umbilical supports from the home system of the Corporation, never entirely being free until, if they could, they bought themselves out. The lawsuits to attain self-direction had been making the news lately, Shona recalled. No one had signed on deliberately to make themselves and their children virtual indentured servants, but that was what the suits alleged. Appeals were in and out of court nearly every month. Shona acknowledged that competition did promote more development of the outer worlds by both parties than might have been accomplished by either working alone. Technology had improved geometrically, even exponentially, since the Corporation won permission to compete in the space race. Private industry provided money for research that the government, with more duties to fulfill, could never afford.

Forty minutes might be enough time. Shona had to make a quick decision. "I want an MR image. If it's not too bad, I'll let her go. I can get her leg set and put her on painkillers. Your flight is long enough for her to recover full mobility before you set down, if all goes well. You have another medtech in the crew?" Dr. Muñoz, grimacing, nodded. "She'll have to monitor you, but it should be all right."

The captain let out a whistle of relief. "I was afraid you were one of those port doctors who never saw a real patient."

"I served as a colonial doctor before rotating back here," Shona assured the worried officer as she continued to probe the break.

"Thanks," Dr. Muñoz added weakly, but sincerely, pulling her gaze away from the swelling leg. "I don't want to pass up this mission."

"Even in a body cast?" Shona asked.

"Even that," Muñoz said passionately.

Shona grinned, in spite of herself. "All right. I know how you feel. I'll do what I can."

With the help of the emergency medics, Shona rushed her patient on a gurney to the Space Center's clinic. A magnoscan proved that the fracture was a clean break, as Shona had predicted. In no time, she set the leg, bound her patient to the hips in a quickset cast, and dialed up an oral pain medicine. She wheeled Muñoz back on the gurney, the colony doctor flat on her back, but grinning. The other physician and two more settlers who identified themselves as nurses took the wheeled cart from Shona and pushed it up the tilted gantryway. They still had almost fifteen minutes to spare.

"Good luck!" Shona called after them.

"Thank yooo-oooo," Muñoz's voice echoed from the metal-walled lift. Shona smiled to herself. If it had been her with a broken leg, she'd have begged just as hard for the same chance to go.

"Many thanks, Doc. That was quick, clean work," the captain said, joining Shona beside the ramp's foot. "You sure you wouldn't like to come with us? You're capable, and you're friendly. Do you have a specialty?"

"Environmental illness."

The captain nodded slowly. "I could sure use you."

"Sorry," Shona said, grinning. "I'm bound for temporary reassignment on Earth in a few weeks. I wish I'd met you all six months ago, before this"—she patted her belly—"got started. I'm hoping to get assigned to another mission as soon as the baby's old enough for a nanny. I'm getting antsy already, and there's four months to go before this little one arrives."

"Hope it's a girl," the captain said, tipping a finger toward Shona's bulge.

Shona laughed. "Good luck and happy landing," she told the captain. It was the traditional farewell. They clasped arms, and Shona left the landing bay. The thin Martian sunlight brightened the stark shapes of rocks and lichen on either side of the semi-tubular walkway leading back toward the main domes. A klaxon began to sound, indicating the approach of a ship. She started to make her way out of the bay and back toward the medical center. A crewman in coverall and protective helmet stopped her and read her ID card.

"Oh, it's you, Dr. Taylor. Not going on this one?"

"Nope," Shona said with satisfaction. "Got another mission." The man inadvertently looked down at her tummy, and she winked at him.

"We're going to miss you down there on Earth," he said, grinning. "Soft life you'll have, inoculating cruise patients with mal-de-space. Well, you'd better get going. There's a transport ship landing on Pad Three, and we've got to spray it."

"An empty coming back? I'd better move it. Those bus drivers get impatient at the end of the run."

Shona hustled toward the shielded dome as fast as she could. Her center of gravity had shifted a lot since her pregnancy began, and she wasn't used to it yet. The heavy swaying slowed her down. Behind her, the vacuum-sealed blast doors began sliding shut one at a time. The approaching ship must have been coming in pretty fast. She forced herself to an uncomfortable run. The environment suit's helmet, which she had taken off after leaving the colony group, bounced annoyingly against her back. The last set of blast doors was so close she could almost feel it nip her in the tail as it boomed shut. Panting, she leaned against the transparent side of the tube to watch the landing.

The ship must already have been cleaving atmosphere when she met the crewman in the tunnel, indicating that air-traffic control had waited a little longer than usual to sound the alarm. Just as she slid inside the door, the sirens went off, and the dome across the field, reduced to ambient atmosphere, slid gracefully open. The great ship appeared in the sky. It was just a dot of light at first; then the dot grew to a flame, and the flame became larger and larger as it descended majestically onto the scorched pad. The white tubes and arches flushed with red, reflecting Mars's rusty landscape, until they were swallowed up in a rush of flame and flying dust that battered against the transparent walls of Shona's refuge.

There was a stirring of action at its base, as tiny figures, technicians, ran around it, taking readings and checking fittings. The gigantic dome rose out of the floor on either side of the pad. The two pieces slid ponderously together, then closed and locked with a boom that echoed all the way through the miles of corridor. White steam from the decontamination process surrounded the vessel momentarily, hiding it from sight. Spaceborne parasites and particles which clung to the vessel from its latest drop point would be destroyed by the hot vapor. When the halves of the dome parted, the ship looked clean and shiny. Another host of technicians sent out the gantry to the hatch from another quadrant while the halves of the dome withdrew and sank out of sight. The workers started attaching hoses to the various orifices of the ship. The schedule on transport ships was tight. Refitting was supposed to be accomplished as soon as possible. There was another colony group waiting here on Mars for the use of this one. If any lengthy repairs had to be made, it further pushed back scheduled departures. Watching the frenetic activity with a touch of envy, Shona felt the tension of activity, and loved it, as she had from the day she decided to join the space service. She wished that she could get on another mission right away, but she was simply going to have to wait. She patted her belly.

"Baby, one day you and me're going to get on one of those ships and take off for the stars. Won't you like that?"

Returning from her musings with a sigh, she recalled other beings to whom she was responsible. Clapping herself on the head for her inconsideration, Shona hurried through the dressing rooms and shed her protective suit. The secretary of the Health Department wouldn't keep an eye on her dog forever.

Saffie leaped on her with a joyful bark as soon as she appeared. She was a big animal, with a shaggy black coat and huge paws into which she'd never seemed to have grown. Shona backed against a wall to keep from being toppled over by her pet's enthusiasm. Her balance wasn't as good as it used to be. The dog licked her face.

"Sorry, May," Shona apologized to the secretary, calming Saffie, and hooking a hand through the dog's collar. "I had a medical emergency to take care of."

The older woman clicked her tongue. "It's all right. I don't mind keeping her so long as she's quiet. She never barked until just now, when you came in. I just don't know why you don't have a cat, like everyone else. They're smaller," May said pointedly, looking at Saffie, who looked back curiously, knowing she was being discussed.

Shona laughed as she wound the dog's leash around her hand. "Oh, I do have a cat. But he thinks it's every cat for himself if trouble comes along. I can count on Saffie. Come on, sweetheart. Let's go home." At the sound of the word "home," the dog dragged her eagerly out of the chamber.

There was some measure of envy she met in the eyes of people she passed on the street for having such a large and obviously valuable pet, and a little sympathetic worry in the faces of people who recognized that sometimes on Mars these days, a bodyguard of some kind was necessary, even for a small, pregnant woman. But Saffie was more than a mere companion or theft deterrent. She was part of what Shona liked to think of as her team. Before she came back to Mars to start a family, Shona was a specialist in environmental illness, and Saffie, like the rest of her pets, served a special purpose.

Environmental illness was new, an Industrial Age phenomenon and problem. When apparently unrelated groups of people began to suffer symptoms of fatal diseases, sometimes years after exposure, an EIS was enlisted to trace back the common cause. In a way, the EIS was a doctor, a detective, and mother-confessor rolled into one. In colony work, not only did a doctor have to beware of toxic chemicals or radiation, but also new allergens, histamines, or bacteria. It was Shona's job to locate those stimuli, and try to determine whether the irritant could be moved, vaccinated against, or whether it required the removal of that member of the colony from the source of distress. The government put an EIS envirotech on assignment to a colony where there might be hidden threats to the health of the settlers. Particularly which a number of those on the mission were related to one another such things threatened the survival of the mission. What affected one might affect them all. The Cotton Consortium had been just such a case. Shona had found a tendency in the family members for a kind of anemia which could lead to leukemia, and had persuaded the patriarch, with considerable difficulty, not to build their colony center on a site which, though otherwise suitable, stood over a natural source of mild radioactivity, a condition which practically guaranteed trouble somewhere up the time-line.

Saffie was a vaccine-dog. Her breed had been created from a standard Earth strain which had an unusually efficient immune system. A vaccine-dog, when injected with an infector, generated antibodies to combat it faster than any comparable mechanical unit ever invented. The dog's handlers had to move quickly to extract a sample of the antibodies to synthesize before the dog's very healthy system cleared out all trace of the test. It meant Saffie had never had a sick day in her life. She even seemed to repel parasites and vermin. Shona was envious, considering how many organisms on new worlds seemed to like to taste human flesh.

The mice were a new strain of Harvard mine-canary mice first bred in the late twentieth century, similar to humans in their sensitivities to carcinogens, but multiplied several hundred or thousand times. It was a nuisance to notify the Health Department every time there was a new litter of mice, but it kept her from being raided by the exterminators. Martian law made very little differentiation between mice used in scientific experiments and wild rodents.

Cancer had been licked about a century past on Earth, but it was still one of the most prevalent ailments to trouble humans wherever they went. Shona was too attached to her brood of mice to sacrifice one whenever it caught the local strain of cancer or pneumonia, so she did her best to cure them, using genetic vaccine strains available commercially, or employing Saffie's talents. Shona never named the mice. As a hybrid bred particularly for their susceptibility to disease, they didn't live long, and she hated to get as attached to them as she did to her other animals.

Besides Saffie and the mice, there was a pair of dwarf, lop-eared rabbits, fancifully named Moonbeam and Marigold, whose job was mostly to test native food for its side effects. If the lops refused to touch a comestible, Shona recommended against its use by beings of Terran origin. Of course, the colonists didn't have to pay any attention to what she said. That was their choice. But her rabbits were seldom wrong.

Shona's cat, an Abyssinian, was named after her uncle Harry. When he deigned to do his job, Harry the cat's sensitive nose was better than any bloodhound's in locating the source of escaping gases or finding faint traces of chemicals. Normally, cats were sight hunters, but Harry's line had been bred to take advantage of the sophisticated feline sense of smell, and he was raised among dogs. Shona had an array of instruments to determine what the gases were once the cat had pinpointed them, but she didn't need the devices if the mix included sulphur, because Harry would pointedly throw up as close to the source as he could. It was one of Harry's less endearing traits. He was also good at hunting down small animals and larger insects that had been in the colony camp. Specimens, sometimes alive but just as often dead and in one or more pieces, often ended up in her slippers. She appreciated the gesture. It meant the family feeling between them was mutual.

"You just like animals," her husband Gershom had once accused her, with a twinkle. "Your job is a good excuse to have your own zoo."

Strictly speaking, the ottle wasn't part of her menagerie at all. He, she, or it was an intelligent, sentient visitor, more or less permanently adopted by Shona from his home world. "Ottle" was the human name for the species, because it resembled a combination between Terran turtles and otters. The flat, disk-like body's shape was similar to that of a Terran turtle, but it was as flexible as an otter's, and it was covered with smooth, shiny fur, for the ottle was a littoral creature. The species had been discovered by an exploration team evaluating the ottle world for potential use as a pastoral colony planet. The humans and the indigenous species were surprised to see one another.

Once communication had been established, the exploration team discovered that the population of the new find was remarkably intelligent, and most interested in learning more about its new friends. Though they had no mechanical devices of their own, they had a highly developed language and culture, which had not heretofore accepted the existence of other intelligent species in the universe. Whether or not any of the newly named "ottles" should accompany the human team off-world was the subject of hot debate in the ottles' loose form of parliament, but it was eventually resolved in favor. A number of the aliens, Chirwl among them, rode back to Mars in the exploration vessel, which they found as inexplicable as the humans themselves. Some of them, like Chirwl, were trying to find a way to explain the existence of machines, and humans, in terms congruent with ottle philosophy. Chirwl spent most of his time researching his own thesis to see whether machines were natural offshoots of humankind or not.

The laws regarding the hosting of an ottle were very strict. The government had made it clear to the aliens that if ever one expressed a wish to leave; it was the responsibility and the expense of the host family to have it transported back to its native system, a pair of large binary worlds circling a small yellow sun not unlike Sol about twelve light-years away. Shona's guest wanted to travel and see the galaxy. He didn't seem unhappy to be temporarily relegated to a ground post while Shona carried her baby to term. In fact, he was as much interested in the process of human gestation as he had been in her travels on missions for the government. The relationship would terminate only when Chirwl decided he wanted to go home. At regular intervals, a government representative from Alien Relations visited them to make certain Chirwl was happy and healthy.

He was very intelligent and keen to learn all about his host species. Sometimes Shona felt it was like talking to a rocket scientist only imperfectly acquainted with the English language but light-years beyond her in terms of knowledge. At other times, she found herself explaining the most basic things carefully in words of one syllable, as if the ottle were a small child. That was just one of the natural incongruities of their relationship. He knew nothing of human interaction, and didn't understand why humans, so much greater in size than he, tended to be afraid of him, nor why it was safe to walk some places in Mars Dome #4, and not in others.

It had been easy to afford her menagerie on wages paid for space service, even for a physician as inexperienced as she was. The much smaller stipend, stripped of the bonuses and hazard pay she got for grounder work while on family leave, didn't make a patch on her previous income. It was Shona's only regret for taking three or four years out of the middle of her career that she would have to learn to economize. Gershom sent home money occasionally, but his trading ship, the Sibyl, was always eating up extra income for repairs and licenses bought in each new system the Sibyl opened trade in. Shona felt herself fortunate that the government gave her a partial subsidy for the care of her animals as being part of a very effective though expensive medical evaluation team.

Most of the time, she was simply glad of their company. She and Gershom had been trying for some time to start a family. It wasn't until, during a physical examination, the unexplained tenderness in her breasts and belly led to a test that showed there was a baby on the way. Instantly, she'd messaged the good news to Gershom via tachyon squirt, and started looking around for a place for them to live. She had intended to spend the rest of the pregnancy and the first couple of years enjoying her child's infancy here on Mars. Her pay was pulled back to match her temporary assignment as ground staff, but that concerned her less. The one thing her salary couldn't buy her was preferred living space.

The Housing Authority had been sympathetic but unable to help her. Mars was suffering from its perpetual housing shortage, and her budget was limited. Her application for living quarters for herself and the animals went on a waiting list. She needed a lot of space because of the menagerie, and was grateful that it was usually quiet. There had been more than one neighbor of the domes who had had to move to a remote dome because he owned a noisy pet. Shona had the additional excuse not only of additional room, but for remaining in the main domes, that her animals were part of her work. They couldn't promise her anything sooner than the date of the baby's arrival, and possibly not even that.

During her visit to Mars, she had been staying with her Uncle Harry and Aunt Lal, in the vacant room which belonged to their eldest daughter, currently away at University. It was the same chamber that had been Shona's while she was growing up in their care. She appealed to her aunt and uncle to let her live in it until she could find a place of her own. A good deal of her impedimenta had been placed hastily in storage.

There were some times Shona was grateful that her relatives welcomed her back. She loved her four young cousins like brothers and sisters. Angie and Stevie, in particular, were her devoted followers. At others, she wished she could be living anywhere else, even in those frightening abandoned buildings near the Space Center. The crowding in the small dome was nearly as bad as it would have been on shipboard, a similarity which her aunt, an unabashed groundhog, wouldn't have appreciated. Aunt Lal was scared stiff of anything which smacked of going outside of the domes, let alone blasting off into space.

Since she wouldn't be able to get back to her real work for many months yet to come, Shona was assigned to give the final physicals and examinations to teams about to depart and filled the rest of her days studying the latest digests on her speciality. It was almost as good as going, though not quite. She'd get a small taste of space travel in a few weeks, when she took ship for Earth. There was a law under discussion in the legislature that would ban space travel from Mars for pregnant women and minor children, and Shona had no intention of getting caught by any rule that would ground her for good. She had already made her plans to evade entrapment.

A painful twinge erupted in the small of her back, and Shona stopped walking to massage it. The way her back and feet felt today, she was going to have to cut back on the hours she spent on her feet doing examinations. Saffie, throwing an occasional concerned glance over her shoulder at her mistress, trotted more sedately toward the transport stop. Shona smiled and patted the dog's head.

Behind her, a slight sound disturbed the silence—a hiss, the sound a shoe might make brushing against the pavement. Shona glanced around casually, then warily. There was no one there.

"Hello?" she said. The street was empty. Her voice echoed against the derelict storefronts. She clasped Saffie's leash tighter and wished the transport would hurry.

* * *

Everything in the office suggested power. It did not shout or intrude its message directly on the consciousness, but it implied subtly to an observer that at this desk sat a most important man, with important choices to make that could affect thousands or millions of lives. The desk alone, custom-styled and handmade of the most expensive and rare materials available anywhere in the galaxy, spoke quietly of money and influence.

"Report," said the man seated behind it, addressing the screen of a private communications unit. It was set into a pullout panel at the rear of the expensive Earth-wood desk so that no one walking into the office could see to whom the executive was speaking. "This is a secure frequency."

"Yes, sir." The man on the screen was named Wrenn. His police file described him as an amoral sociopath, brilliant and dangerous. Five years ago an extended sentence for assault he was serving in the Martian Detention Center had been cut short by the intervention of the Corporation executive. He had used his considerable influence to urge members of the parole board to be lenient at Wrenn's last parole hearing. Wrenn felt only minimal gratitude for his benefactor's aid, but he enjoyed the assignments he was given. Wrenn knew that if he tried to betray his employer, there were probably other people like him on the payroll who were as tough as he was. His employer paid him enough so that he could trust Wrenn to keep confidences. The relationship suited both of them. "I finished sorting through the personnel files. There's four candidates whose profiles fit what you wanted. I don't see how a single person's going to help you keep better control of the colonies."

"Judiciously utilized," the man behind the desk said, "one person will be more than enough, providing that it is the right person. The situation is getting out of hand. I am extremely troubled by the tendency of the Galactic courts to prematurely sever corporate contracts between this office and colonial worlds. After the last outrage, awarding damages to Iomar IV against their claims that the Corporation didn't live up to the clauses in its contract, I can tell that it is time to take a more direct hand. Hence my need for a specialist. Let me see the files."

Wrenn nodded, and leaned toward the video pickup as he located the datacube recess in the public comm-unit and inserted a cube. The executive's screen blanked out and filled with a four-way view, each quadrant displaying the moving image of a man or a woman. The first person was a man in his fifties, mustachioed, respectable in appearance. The second was a young woman, fresh-faced, with freckles and thick brown hair. The third was a thin, black-haired woman in her thirties. The last was a man of forty, round-faced and cheerful. "I think you'll like number two, sir," Wrenn's voice continued over the recorded images. "I followed her home today. She's everything you specified when you gave me this assignment. Like you always said, you want the best tool for the job."

The executive touched a control, and the image in the upper right-hand corner enlarged, filling the screen. He scrolled upward to read her psychological profile. "Very good. Very good. All I desired for this job. Excellent. She would be just right. I do like the policy of establishing psych profiles. Takes a great deal of the guesswork out of finding the ideal person to fit the job. I see this candidate is employed by the government. She was out in space, and now I see she is in a ground-service position."

"Yes, sir. She's pregnant. But she's expressed an interest in returning to active colonial service."

"Hmm," the executive mused, tapping his lip with a forefinger. "I need her available to travel now. The new legislation the Pro-Child League has just intimidated the Martian Council into passing will preclude that." He touched a control which saved the personnel data into a private storage area, and the holotank cleared, showing Wrenn's face. "See to it. Then steer her this way. I want her to join the Corporation, and not the government, once she resumes active service."

Wrenn remained expressionless. "Yes, sir."

His employer cut the connection. Wrenn waited until there was no one passing by before he left the public booth.