Nnedi Okorafor is a novelist of African-based science fiction, fantasy, and magical realism for both children and adults. Born in the United States to two Nigerian immigrant parents, Nnedi is known for weaving African culture into creative evocative settings and memorable characters. In a profile of Nnedi's work titled, "Weapons of Mass Creation", the New York Times called Nnedi's imagination "stunning."

Nnedi's accolades include the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel for Who Fears Death. Her young adult novels are Akata Witch (an Amazon.com Best Book of the Year), Zahrah the Windseeker (winner of the Wole Soyinka Prize for African Literature), and The Shadow Speaker (winner of the CBS Parallax Award). She is a professor of creative writing and literature at the University of Buffalo.

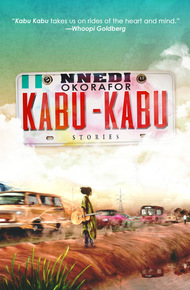

Kabu kabu—unregistered illegal Nigerian taxis—generally get you where you need to go. Nnedi Okorafor's Kabu Kabu, however, takes the reader to exciting, fantastic, magical, occasionally dangerous, and always imaginative locations you didn't know you needed. This debut short story collection by an award-winning author includes notable previously published material, a new novella co-written with New York Times-bestselling author Alan Dean Foster, six additional original stories, and a brief foreword by Whoopi Goldberg.

The success of Nnedi Okorafor's ventures has always fascinated me, particularly since she manages to write and fully embrace her Nigerian cultural heritage while weaving together memorable characters into evocative settings. – Terah Edun

"In her first collection of short fiction, she draws on the same combination of resources that have given her a unique voice — African trickster tales, post-apocalyptic scenarios, distant planets with societies influenced by Nigerian mythology, tales of young Americanized Nigerians confronting their ancestral culture in visits to Africa. . . . There is playfulness and wonder in these tales, but also some sobering realities."

– The Chicago Tribune"Okorafor's genius has been to find the iconic images and traditions of African culture, mostly Nigerian and often Igbo, and tweak them just enough to become a seamless part of her vocabulary of fantastika. . . . An important collection by a writer to listen to."

– Locus"In this vibrant collection of speculative fiction, Okorafor proves yet again that she is among the 21st century's most significant and noteworthy science fiction authors. The American-born author features her parents' Nigerian homeland in many of her stories, casting a sympathetic but informed eye on that nation. . . . With a knack for dialogue and an ambitious imagination, Okorafor effortlessly blends original characters with fantastical elements into the vivid scenery of Africa to create stories worth reading again and again."

– Publishers Weekly, starred review"Kabu Kabu takes us on rides of the heart and mind."

– Whoopi GoldbergHow Inyang Got Her Wings

She circled high above her village, looking down. It would be the last time she ever saw it as it was. Okokon-Ndem, Calabar, Nigeria, 1929. The rectangular adobe sleeping quarters with cooking fires burning in front of them. Built in a circle. A courtyard in the center. The spaces between the huts filled in by forest. Yam and manioc farms close by. Her forest village, her mother, her father, her sister, her sister. She had only one friend and he was over one hundred years old. The others she resented, but they were her people, so she loved them too. Except Koofrey. She would always hate him.

She shed no tears. Instead, she looked ahead. To the east. The sun was rising. It would soon be time to go. She sighed. It had all really started with that dream.

#

Levitation

She sat in a round clearing surrounded by ekki, iroko, idigbo, obeche, camwood, and palm trees that fondly bent their leafy heads toward her. Before her was bliss. Ripe bright orange mango slices. A palm leaf heavy with thick disks of boiled yam, soft but firm, dripping with palm oil and red pepper. A pile of buttery biscuits. Split coconuts, the insides lined with thick white coconut meat. Sweet sweet fibery oranges, peeled and separated into juicy sections.

Beside her, a boy wearing blue beads around his neck handed her a green bottle of palm wine. She grinned at him. Whoever he was.

She'd tasted palm wine once when her father had left a gourd of it beside the cooking fire. She'd drunk from the gourd and ended up stumbling around with a grin on her face. Later, she'd received a terrible beating but not even her mother's strong hands could beat out the memory of how delicious palm wine tasted.

Now, she took a deep gulp. It was warm and sweet, just the way she liked her fruits. The wind blew the treetops and the sound of the shushing leaves distracted her momentarily from the bounty before her. She and the boy looked up into the sky, the grins on their faces widening. Their teeth were white, their skin dark brown and they didn't need a moon to know where they were.

#

Inyang woke with gummy eyes, nostrils flaring, mouth agape, gasping for air. She inhaled loudly. All was black and her heart fluttered. But tonight's a full moon, she thought, frowning. So why can't I see? She tried to raise her head. It hit something solid and stars burst before her eyes.

"Ah!" she hissed. "I've been buried alive!" Her grogginess quickly dissipated as her mind started working on a plan to dig herself out.

She turned her head and saw a wall gecko, pink blue in the moonlight. Moonlight, she thought. The wall gecko scampered to a corner, disappearing into the shadows. She tried to rest her neck. There was nothing to rest it on. She shuddered and fought for something to hold on to. Then she dropped from several feet, coming down hard on her straw stuffed bed with a painful thump. She rolled sideways to the floor.

"Oh no, not again," her oldest sister, Nko, groaned from her bed across the room. "You're too old for this."

Her middle sister, Usöñ—whose bed was closest to Inyang's—continued snoozing away.

Inyang got up slowly, her legs shaky. She rewrapped her blue and white rapa around herself. Her head ached but this time she remembered. This time she'd been awake when it happened. She rubbed her temples. She hadn't just rolled out of her bed.

"You okay?" Nko asked, rubbing her short hair, her collarette of beads and cowry shells clicking and clacking as she turned to look at Inyang. The straw in her bed crackled as she sat up.

Inyang nodded, pushing her long coarse hair from her face. She picked up her dark blue head wrap and rewrapped her locks. She looked down at herself and her eyes widened. "Nko! I've been wounded!" she screeched, pulling up her rapa and looking at her legs. But there was no sharp pain, only a dull ache.

There was more clicking and clacking as her sister Usöñ, abruptly sat up. "Wha . . . shut up, Inyang," she mumbled, still half-asleep.

"Open the curtains, Usöñ," Nko ordered. "She rolled out of bed again."

Usöñ mumbled as she dragged herself up and pulled open the curtains to let in the moonlight. Nko's many folds of fat jiggled as she hurried to Inyang. "Let me see," Nko said, breathing heavily. Even after several hours of sleep, Inyang's sister smelled like baby powder and the scented oil. Usöñ ambled over, also slightly breathless. The three girls stood in the middle of the room like two healthy baobab trees around a palm tree. Nko pulled at Inyang's blue loincloth and Usöñ started laughing. The blood soaked through the cloth just below Inyang's belly.

"You're fine, Inyang," Nko said, a smirk on her face.

"I'll go tell mama and grandmother," Usöñ excitedly said, running out of the room as fast as she could, which wasn't very fast at all.

Inyang stood there, afraid to move. Her two sisters, who were two and three years her senior, had never spoken to her about how they'd gotten their menses. Thus far she felt no pain other than a dull throb in her abdomen but she wasn't sure. Her mind was reeling. Blood on clothes. Had nose to ceiling. Blood on clothes. Had nose to ceiling. She felt dizzy and she wanted to sit down. But she had blood on her rapa. And so she was standing there frowning as she sucked a strand of mango from between her teeth.

#

The next day, Inyang floated in the deeper part of the river, staring at the sky. She was glad no one was around. Mildly nauseous, she could feel the blood seep from between her legs with every movement. Earlier that day, her family had celebrated the coming of her menses with a small afternoon feast. She was n-kaiferi now. However, even she knew this didn't matter. She would not be circumcised and secluded for weeks in the m-bobi, the fattening hut that made girls beautiful. Nor would she be betrothed to a man. Ever.

In all her fourteen years, she'd never been so aware of her dada hair, the long thick locks of tightly twisted hair she'd been born bearing. They marked her as bizarre, potential bad luck, and unmarriageable. Still, because her family loved her, her father bought her a red loin-roll and her sisters decorated it with beads and cowry shells. Her father didn't bother buying the embroidered multi-colored cap that went with the n-kaiferi outfit. It wouldn't have fit over Inyang's long ropes of dada hair.

Inyang had reluctantly danced with her sisters and the other girls. Normally, she would have reveled in the food and laughter and especially the dancing. Inyang loved to dance. Sometimes when she was outside preparing dinner and night was approaching, she'd dance to the rhythm of the forest. Inyang wasn't a small girl, nor was she thin. She was tall for her age and strong and she ate healthily, though she was nowhere as large as her gorgeous sisters. But this afternoon, she wasn't hungry. Her grandmother had smiled at her, handing her a slice of sweet mango, her favorite. This Inyang was able to eat.

"It'll pass," grandmother whispered.

But she knew her grandmother was wrong. Inyang was born the way she was and something strange was happening to her. In her dreams, she had always flown. High, past the trees. Into the clouds or blue clear sky, depending on the weather she experienced during the day. In these dreams, she always felt a current of wind spiraling around her, clockwise, moving her with ease. These dreams always ended with a jarring crash to the ground, and her waking up rolled out of bed. But this time, she'd been eating a feast and when she woke . . . she'd been above her bed. She'd told none of this to her parents when they came to examine her.

Inyang hugged her secret close to her chest and waded back to the riverbank. She pulled herself out of the water, not bothering to look around. Though tradition told her to, she wasn't ready to become so conscious of her nakedness. She arched her back and stretched her arms, letting the sun bathe her body. When she was dry, she wiped away the dribbling blood, tied the rag between her legs and around her hips and wrapped her blue green cloth around herself. She tilted her head back and looked at the sky again. A slight breeze tickled her cheeks. Then she knelt down and got to work. She had a large basket of clothes to wash and it would be dark in a few hours.